12

Putting Things in Order

11.1 Overview of Arrangement

Just like a good movie, an argumentative research essay has a beginning, middle, and an end. Regardless of the scheme you choose, it is important to think of the beginning as a good place to incorporate ethos, the middle as a good place to incorporate logos, and the end as a good place to include pathos. In other words, establish your credibility in the introduction, construct a sustained logical plea to your reader through use of reasoning, examples, and statistics to support any claims in your argument and, in the end, appeal to the emotions of the audience to spur them to action in by adopting an idea or taking some action. Of course, these appeals should be used throughout the essay, but the ethos-logos-pathos progression is something to keep in mind as you compose.

The three most implemented schemes for arrangement are the Classical, Rogerian, and Toulmin models. In the most basic form of the Classical model, the project is divided into the introduction, background, thesis, elaboration of the thesis, refuting opposing arguments, and the conclusion. The Rogerian model focuses primarily on establishing common ground, and is commonly divided into these sections: introduction, explanation of opposing view (objectively), explanation of primary view, finding common ground. The Toulmin model is a more visual way of organizing and thinking about your ideas in terms of your claim and evidence, and includes the following components: claim, reasons, warrant, backing, qualifier, and rebuttal.

11.2 The Thesis

In many ways the thesis is a bridge between invention and arrangement. It is at once the final step of invention and the first step of arrangement, since in the classical argument structure every section, every paragraph, and every sentence should go toward convincing your audience of the thesis. At the same time, it is important to remember it is a two-way bridge, with many lanes of traffic. The process of invention doesn’t stop with the thesis statement. It is a continual process, even when you are in the middle of the paper and suddenly a new means of persuasion dawns on you. Sometimes you may have to go back and reinvent your thesis to account for new revelations, epiphanies, or tangents you encounter as you write.

Some have noted that the process of invention is more a process of elimination than it is one of creation. As was noted in the invention chapter, coming up with an original idea is largely a matter of eliminating what has already been said about a particular topic to see what remains. Whatever is left over, whatever has NOT been talked about, is original. But finding it is often difficult, especially in topics that have been discussed ad nauseum. If you plan on writing a paper about abortion, for example, you are going to have an exceedingly difficult time finding something that hasn’t already been said. In highly polarized issues like this, it is often the complications that are productive in terms of originality. By complications, I mean those things that complicate the issue and make it less black and white or bring the polarized sides closer together. Any argument that expands the common ground between the pro-choice and pro-life positions holds promise in terms of originality.

A thesis typically starts with the basic building blocks of an argument, which are claims and reasons.

11.2.1 Claims

In the simplest terms, a claim is a statement you are making about reality that can be agreed or disagreed upon. A claim is arguable. Now, note that a claim is a statement, so questions don’t really count. Your research for the argumentative research essay might begin with a question, or even multiple questions, but it doesn’t become argumentative until it makes a claim. The simplest claims are answers to questions of fact or definition.

11.2.1.2 Claims of Fact

For example, the following claims might arise from the questions that are paired with them.

- What color is your dog?/My dog is yellow and brown.

- How long is the Brooklyn Bridge?/ The Brooklyn Bridge is 6,016 feet long.

- When are you going to see the movie?/We are going to see the movie at 10:35.

- Why is the average global temperature rising?/Greenhouse gasses are eroding the ozone layer (this is a causal claim, which demonstrates a relationship between two events).

- How are you today?/I am fine.

Note that these are all questions of fact. Even so, they are all arguable since they could be lies or misconceptions. These next claims are answers to questions, to be sure, but they are not arguable because the final judge is the person uttering the claim:

- I think that dog is ugly.

- I envision a world where dogs and cats live together in perfect harmony.

- I believe in ghosts.

- I have a dream.

Alright, you might say, these could still be lies, but they don’t really make good claims for arguments because the only evidence for or against them is the testimony of the person making the claim. Of course, you could argue that the person making the claim is not psychologically fit to know what they think, or that society has conditioned them to believe whatever it is they say they believe, but these are rabbit holes best avoided. To create a solid foundation for your argument, it is best to stay away from claims like these.

11.2.1.3 Claims of Definition

Any of the above claims of fact could easily be transformed into claims of definition. For example, if you claim you are fine and you don’t look fine, then someone who knows you well might question exactly what you mean by fine. Does fine mean only that you are physically in good condition, you know, breathing, walking, talking, and that kind of thing, or does it mean that you are mentally, physically, and spiritually at the top of your game. Here are some claims of definition:

- A person who is fine is someone who does not feel sick.

- The Brooklyn Bridge is the roadway that extends from the curb at Park Row in Manhattan to the curb at Sands Street in Brooklyn.

- Yellow is visible light with a wavelength between 565 and 590 nanometers.

- Anything that is not brightly colored is ugly.

11.2.1.3.1 Genus and Species

Aristotle has a well-worked out system of definition. He composed a whole book about it called Categories. He says, essentially, that definition is a process of finding the differences that distinguish things or ideas similar things and ideas within a genus. A genus is, essentially, a larger category to which the item is said to belong. A species is a set of objects or ideas within a genus.

11.2.1.3.1 Categories

In the simplest terms, Aristotle’s definition is a process of systematically identifying one thing from another by pointing out what is different about that thing from the other in terms of these ten categories:

- Substance

- Quantity

- Quality

- Relation

- Place

- Time

- Position

- State

- Action

- Affect

He gets quite detailed about what kinds of things constitute these categories. You can find a good list, with examples, at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Categories_(Aristotle).

Aristotle’s approach seems to make sense. If you can’t find any difference between two things, then they are the same thing. Look at this example; maybe it will help:

Now try to define something like “good” or “beautiful,” using this method. This becomes a little more difficult, and you are likely to find that your claim of definition quickly turns into a claim of quality.

11.2.1.4 Claims of Quality

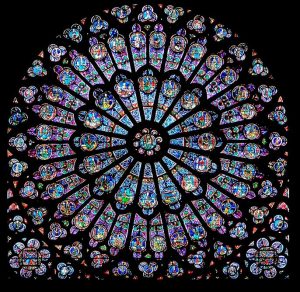

Some of the above claims of definition border on claims of quality or value, especially the last one. Anytime you get close to defining abstract qualities, especially those that make some kind of judgement as to their value or worth, you are likely also dealing with claims of quality. Usually, claims of quality make a comparison between actions or things that are good/bad, desirable/undesirable, beautiful/ugly, and so on. They are often subjective, and nearly as often represented as binaries, with no middle ground. The difference is in the application of an agreed upon definition to a particular action or object. For example, if you were to say that the Rayonnant rose window in Notre Dame de Paris is beautiful, you first need to have agreed on a claim of definition – what constitutes beauty?

Stasis, remember, progresses linearly from one type of argument to the next, so before arriving at a claim of quality in regard to something particular, the audience must first have agreed either explicitly or implicitly to a claim of definition. For instance, if your claim is that Bart’s shirt is pretty, your audience must first have agreed to the claim of definition that yellow is pretty, in addition to the claim of fact that Bart’s shirt is yellow. This can also be stated in the terms of deductive reasoning discussed in the logos chapter.

Major Premise: Yellow is pretty (a claim of definition). *

Minor Premise: Bart’s shirt is yellow (a claim of fact).

Conclusion: Bart’s shirt is pretty. (a claim of quality or value).

*To be fair, Bart’s shirt could be full of holes and spattered with red and blue paint, which some might say make it not pretty. A more bulletproof deductive argument, then, might be Anything that contains yellow is pretty, Bart’s shirt contains yellow, therefore Bart’s shirt is pretty. But here is the thing – bulletproof arguments like this rarely develop organically in the real world, so don’t be afraid to move forward with less iron-clad reasoning if necessary.

Here are some claims of quality:

- Pepsi is better than Coke.

- It is better to ask for forgiveness later than seek permission now.

- People should reduce, reuse, and recycle.

11.2.1.5 Claims of Procedure

A claim of procedure is at the heart of every proposal argument. It answers the question, what should we do about it? Unlike the other three types of claims, the claim of procedure asks its audience to do something. It is a claim of action.

The distinguishing features of the procedure claim include an extremely specific audience and a very specific action for that audience to take. The use of the word should is usually a good tip off that the claim is one of procedure.

Now, you may notice that the last claim listed under the claims of quality section has the word should in it, which might make you think it is a claim of procedure. What it is missing is a specific audience. In this claim, the audience is composed of individuals who can each act on the claim, but as a rule, they only have the resources to act on it for themselves, making the resulting argument only a veiled form of “it is good for people to do such and such.” This is fundamentally an argument of quality. If you say that Elon Musk should incorporate the principles of reducing, reusing, and recycling into his Tesla manufacturing plants, then we have a claim of procedure.

Here are some claims of procedure:

- Springfield Elementary should raise the salary of their teachers by 10%.

- Moe’s Tavern should introduce a drive-thru open container service.

- Mr. Burns should incorporate stringent safety protocols in the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant.

11.2.2 Reasons

In a procedure argument, the reason is typically identified as an answer to a question of the form Why should I? (See !@# Assertibility Questions). Consequently, the reason can usually be prefaced with because. For example, the assertibility question for the first example above would be:

Why should Springfield Elementary raise the salary of their teachers by 10%?

To which you might reply:

- Because a higher salary will attract more qualified teachers.

- Because the work teachers perform demands better compensation.

- Because teachers who are paid well are measurably more effective educators than those who are paid poorly.

While these reasons all meet the assertibility test, the reasons in the examples below don’t quite hit the mark.

- Because pigs don’t fly.

- Because night follows day.

- Because a cat has four legs.

In these cases the conclusion does not follow from the premise, or in the current terms, the claim is not supported by the reasons. They are not reasonable reasons because they are non-sequiturs.

A reason is what ties different forms of evidence to your claim. To review, the four main types of evidence include statistical, testimonial, anecdotal, and analogical.

11.2.3 Enthymemes (or Claims and Reasons)

By now, let’s assume that you have narrowed your claim down to something specific. You have discovered some solution to a problem that has not yet been discovered. You are ready to write a thesis statement. Here is one way to write a thesis statement for a proposal argument using enthymemes. An enthymeme is, very simply, a claim and a reason. In a proposal argument, the claim also names the audience, whereas in some other types of argument that is not necessarily the case. So, a proposal argument pretty much has to begin with a clear idea of an audience that can make the change you propose in the claim. Let’s take Hunter S. Thompson’s campaign pledge to destroy all paved roads in Aspen and turn them in to parks, planting them with trees, flowers, and grass. As Sheriff, he wouldn’t have really had the power to do that even if he would have won the election, so he would have had to address a proposal to the entity with the power to make the change – probably the Aspen City Council. Using Thompson’s campaign pledge as an example, here is the method of creating a thesis statement with enthymeme:

11.2.3.1 Step 1: Create a Claim

Create a claim by stating what you want an audience to do, usually by means of a should statement.

(claim = audience + “should” + do)

In this case the claim would be as follows:

The Aspen City Council should replace all paved city streets with parks.

11.2.3.2 Step 2: Create a Reason

But that is not quite an enthymeme since an enthymeme needs a reason.

Step two is to create one or more reasons why your audience should do what you want them to do, in the form of because clauses. Since Hunter S. Thompson was a resident of Aspen, one of his motivations was to reduce tourist traffic in town. Thus, we have a reason for the action, which is to reduce traffic in town. Transformed into a “because” clause: because doing so would reduce traffic in town.

(enthymeme = claim + “because” + reason)

The following is the enthymeme:

The Aspen City Council should replace all paved city streets with parks because doing so will reduce traffic in town.

This enthymeme could stand alone as a thesis, or we could add further reasons, like this example in Step 3:

11.2.3.1 Step 3. Use your enthymeme as the thesis or add multiple reasons.

The Aspen City Council should replace all paved city streets with parks because doing so will reduce traffic in town, reduce pollution, and save money on traffic enforcement. This thesis will then guide your project from here on, providing direction in times of doubt. Should you become lost while organizing your project, refer back to the thesis and ask yourself “How can this paragraph or section go toward proving my thesis?

11.3 The Classical Model

Below is a simplified version of the classical model of argument:

I. Introduction

II. Background

III. Lines of Argument

IV. Alternative Arguments

V. Conclusion

Let’s look at the individual elements in order.

11.3.1 Introduction

11.3.1.1 Purpose

In the most general terms, the purpose of the introduction is to orient your potential reader to the rhetorical occasion you are addressing. It should at the very least explain your purpose in putting words on paper. You should know the answers to the following questions before starting:

- Why are you writing?

- What are you writing about?

- Why are you writing about it?

- Why are you writing about it now?

- Why is it important?

- To whom is it important?

11.3.1.2 Patterns

Introductions to argumentative research essays follow a typical pattern, but that doesn’t mean you can’t deviate from it. The introduction should start in general terms and, like an inverted triangle, tell the reader just what they need to know to understand and appreciate the thesis statement. If you are using the classical argument rather than the Rogerian or delayed-thesis argument, the thesis statement will mark the end of the introduction and should be showcased by it. That doesn’t mean, necessarily, that the thesis statement will be the last sentence of the first paragraph, since longer essays might require several paragraphs of introduction. Here are some things you can do in the introduction.

11.3.1.2.1 Classic Pattern

11.3.1.2.1.1 The Bait and Hook

If the stuff that happens in the introduction between the title and the thesis statement can be thought of as the hook, think of the title and the first sentence as the bait. The purpose of these two initial elements is primarily to attract a reader. It is okay to be a little flashy here, but just like real fishing, getting too flashy or too complicated right up front might have the opposite effect and scare the reader away. It is important to remember also that you aren’t just trying to be flashy for the sake of being flashy – your bait and hook should be tied directly to your aim, otherwise you’ll be guilty of the bait and switch, which will negatively affect your ethos right from the outset.

Generally, the title and the first sentence should do two things:

- Engage the curiosity of a potential reader

- Give some sense of what the essay is about

If you anticipate your intended audience is highly resistant to your topic, you can easily turn them away by being too contentious in your title. You will have to find some way to show them that the argument you are going to make is somehow different than the many they have heard before and already rejected out-of-hand. Make no mistake, in a classical argument you are going to make a strong argument, but if your audience rejects it, you want them to a least have a chance to understand your stance before they do.

11.3.1.2.1.2 Anecdote

The anecdote is a mini story, stripped of any unnecessary or irrelevant elements. The elements that apply to fiction apply here: setting, character, and plot. Basically, tell your reader about something that happened to someone somewhere. The story could be about an experience you had or an experience someone else had, but it should be true. Most importantly, the anecdote allows you to show the reader something about your topic. Depending on the situation, limited use of the “I” voice is okay if the anecdote is from your personal experience. A few examples of anecdotes from my own experience are provided below.

In the late ‘80s I drove an armored car. It wasn’t really armored in any special way, though. It was just a primer grey Ford van with a magnetic sticker on it that said, “Western Armored Service.” On my last day of work, I went into Wells Fargo to pick up five thousand dollars in quarters. When I returned to the van with the money on a handcart, I realized I had carefully locked the keys inside the armored vehicle along with the sidearm I was required to carry to protect myself and the money. Luckily, 1988 Ford vans were easy to break into with wire coat hangers stolen from coat closets inside banks. To prevent similar mishaps in the future, Western Armored Service should upgrade their fleet to newer vans with keyless entry systems and provide more extensive training for their drivers.

11.3.1.2.1.2 Question

Beginning an essay with a question can take advantage of natural curiosity to engage a reader immediately. A question that has been raised and not answered is unsettling to most people, so when confronted with a question they don’t have an answer to, they are compelled to read further.

The rhetorical question and hypophora are two types of questions that can be used to open a discussion. The rhetorical question asks a question that has no immediate answer, provoking further discussion, while hypophoric question raises a question only to have the writer immediately answer it. The hypophoric question can pair with your thesis, making your thesis the as yet unsupported answer.

11.3.1.2.1.2.1 Rhetorical Questions

- Shall we stand and fight with our fists?

- Is the government going to come to our rescue every time we run into a little trouble?

- Who will speak for the speechless?

11.3.1.2.1.2.2 Hypophoric Questions and Answers

- How can we attract more qualified teachers? We can attract more qualified teachers by making their pay commensurate.

- How can we reduce noise pollution in the neighborhood? We can reduce noise pollution in the neighborhood by banning the use of power mowers in residential neighborhoods.

- Who can stop global warming? No one can stop it, but we might be able to slow it by reducing our dependence on fossil fuels.

11.3.1.2.1.3 Startling Fact

A startling or little-known fact regarding your topic can quickly draw the interest of the reader and prompt them to continue reading:

- 99% of Springfield residents believe that Mayor Quimby lost the popular vote in the last election.

- The price of a beer at Moe’s Tavern has increased by 200% in the past year.

- Three people have been attacked by bears at the Springfield City Dump in as many months.

11.3.1.2.1.4 Quote

One popular way of capturing the interest of an audience is to begin with a pithy quote. As with any of these attention-getting techniques, make sure it speaks directly to your thesis. Also note that beginning an essay in someone else’s words can have negative rhetorical effects as well as positive.

- “If you don’t like your job, you don’t go on strike. You just go in every day and do it really half-assed,” says Homer.

- According to Chief Wiggum, it is better to “let a thousand men go free than chase after them.”

- “Shoplifting is a victimless crime. Like punching someone in the dark,” says Nelson.

Note that while it is tempting to use the dropped quote followed by an explanation pattern for the first sentence, it doesn’t work that much better there than anywhere else in the essay:

“Shoplifting is a victimless crime. Like punching someone in the dark.” This quote, uttered by Nelson in the Simpsons Season 7, Episode 11, reminds us of the staggering impact of people refusing to wear seatbelts when driving.

What you have to watch out for when using someone else’s words to start your essay is that the quote will steal the show. You risk confusing the reader by making your first paragraph about the quote and the circumstances under which it was spoken rather than your essay.

11.3.1.2.1.4 Provocative or Satirical Statement

If you came up with Nelson’s quote above on your own, you could use it as a provocative statement, causing the reader to wonder is this author seriously saying what I think they are saying? This usually involves stating something ridiculous, then moving back on it in a while this is not exactly true, it is true that… move. If you can turn around and tie it to your thesis, that is fine, but it takes some finesse.

- Pigs can fly. That doesn’t mean they have wings, it just means that they can be raised in one part of the world and flown by 747 to another part, as they recently were to replenish China’s sow herd after an outbreak of African swine fever decimated it.

- Many experts recommend eating tree bark. However, it doesn’t taste very good, and the experts referred to here are survival experts who only recommend it in a survival situation. Otherwise, there are a variety of other options for anyone who wants to experiment with a meatless diet.

11.3.1.2.1.5 Background

The introduction should contain enough background information for the audience to understand and provide context for the thesis. In the classical argument, the background section will further tell the story of the conversation that surrounds your argument. The background should also answer the “who cares?” question.

11.3.1.2.1.6 Thesis

Generally, your thesis marks the end of your introduction and moves you into the background section. In some cases, it might be followed by a short discussion of how your argument will be organized or how you plan on proceeding.

11.3.1.2.1.7 Other Items

Other items you can include in your introduction include a statement of why the topic is important to you, a statement of why the topic might be important to your target audience, or some short gesture toward any common ground you share with your audience.

11.3.1.2.2 The CARS Pattern

The CARS (Create A Research Space) pattern of introduction was developed by John Swales and was developed through his study of scholarly research articles in various disciplines. He found these “moves” consistently showing up in the introductions in academic writing:

- Move 1: Establish a territory

- o Step 1: Claim Centrality

- o Step 2: Make Topic Generalizations

- o Step 3: Review Previous Items of Research

- Move 2: Establish a Niche

- o Make a counterclaim

- o Find a Gap

- o Raise a Question

- o Continue a tradition

- Move 3: Occupy a Niche

- o Step 1A: Outline your Purpose

- o Step 1B: Announce your Present Research

- o Step 2: Announce your Principal Findings

- o Step 3: Indicate the structure of the Research Article

11.3.1.2.2 Patterns to Avoid

The following patterns are tempting ways to begin an essay, and while they are sometimes good starting points, they usually prove ineffective in the end. If you use them, use them like a housebuilder would use scaffolding: tear them away when your essay is finished and replace them with a welcome mat and an inviting entranceway.

1.3.1.2.2.1 The dictionary definition pattern

The dictionary introduction begins by defining some key term in the introduction. It is generally ineffective as the first sentence in the introduction, primarily because it is so common. If the reader needs a definition to understand any of the words in your thesis, use a more subtle approach like the appositive phrase to slip them the information later on, preferably not in the first sentence, like this:

- Menetekel, or ominous writing on the wall, can be seen today in many large cities.

- To embiggen, or to make something greater, is sometimes a good sales strategy.

- This idea is perfectly cromulent, or adequate, for our purposes.

Rather than…

- The dictionary defines menetekel as “ominous writing on the wall.”

- The dictionary defines embiggen as “to make bigger or greater, to enlarge.”

- The dictionary defines cromulent as “acceptable, adequate, satisfactory.”

1.3.1.2.2.2 The “since the dawn of man” pattern

It is easy to be drawn into hyperbole when writing an introductory sentence in order to convey the importance of your topic. This often results in the since the beginning of time or since the dawn of man introduction. Here are a couple of examples.

- People have been eating pickled eggs since the beginning of time.

- Since the dawn of time man has wondered why the price of yogurt in the Springfield Grocery Store is so high.[1]

A typical outline of the introduction in the classic model might look like this:

- I. Introduction

- A. Introductory Sentence – startling fact

- B. Short Anecdote

- C. Short Background

- a. Currency

- b. Relevance

- D. Thesis Statement

11.3.2 Background

The purpose of the background section is to identify and explain the historical, social, cultural, political, and geographical context of your thesis. In this section, you invite your audience into the conversation of your argument and bring them up to speed on any significant threads they might have missed. One easy way to figure out what you might want to include here is to answer the topoi questions that are most pertinent to your topic or make it different from other, similar arguments. Most important is what has already been said about your topic that is relevant to the lines of argument or reasons that you will be further developing in the next section.

Some things you can do in this section are as follows:

- Define key terms

- Identify stakeholders

- Discuss the historical context

- Discuss the social context

- Discuss the cultural context

- Discuss the political context

- Discuss the geographical context

- Identify the most relevant issues or controversies

A typical Outline for the background section might look like this:

- II. Background

- A. Historical Context

- a. Early History

- b. Things that have changed

- B. Geopolitical Context

- a. Other locations

- b. Local significance

- C. Current Voices

- a. Stakeholders – the people this matters to

- b. Voices

- i. Past

- ii. Current

- D. Issues and controversies

- A. Historical Context

11.3.3 Lines of Argument (Reasons)

In this section, elaborate on the reasons you set out in your thesis. You can start with the 3-4 main reasons outlined in your thesis, then just unpack those into subheadings, sub-sub headings and so on.

Each subheading can contain a supporting reason or supporting evidence in the form of a statistic, testimony, anecdote, or analogy. This part of the outline might look something like this:

- III. Lines of Argument

- A. Reason 1

- a. Supporting Reason 1A

- i. Primary supporting evidence for Reason 1A (Anecdote)

- ii. Secondary supporting evidence for Reason 1A (Statistic)

- b. Supporting Reason 1B

- i. Primary supporting evidence for reason 1B (Statistic)

- ii. Secondary supporting evidence for reason 1B (Testimony)

- a. Supporting Reason 1A

- B. Reason 2

- a. Supporting Reason 2A

- i. Primary supporting evidence for reason 2A (Statistic)

- ii. Secondary supporting evidence for reason 2A (Anecdote)

- b. Supporting Reason 2B

- i. Primary supporting evidence for reason 2B (Testimony)

- ii. Secondary supporting evidence for reason 2B (Analogy)

- a. Supporting Reason 2A

- C. Reason 3

- a. Supporting reason 3A

- i. Primary supporting evidence for reason 3A ((Testimony)

- ii. Primary supporting evidence for reason 3A (Anecdote)

- b. Supporting Reason 3B

- i. Primary supporting evidence for reason 3A (Analogy)

- ii. Primary supporting evidence for reason 3A (Anecdote)

- a. Supporting reason 3A

- A. Reason 1

There is no hard and fast rule for how many supporting reasons or examples of supporting evidence that need to be under each heading. Well, there is one rule: No A without a B. That just means that every point should have at least two subordinating points, since if it doesn’t have two points, it is really the same thing as the point it is initially listed under.

Also, the types of evidence in parentheses are in no special order. You can arrange the sequence of these in different ways for different effects. Just like in music, there are eight notes in the major scale, but with these a seemingly infinite number of unique songs can be created. The same goes for constructing an argument. Writing these four different types of evidence, along with other elements of your composition influences the affect of your argument.

11.3.4 Alternative/Opposing Arguments

The alternative/opposing arguments section should have two elements. They are a summary of opposing arguments and a refutation of opposing arguments.

11.3.1.1 Summary

The summary of each opposing argument should be written in plain language, avoiding any sarcasm and needs to avoid employing the straw man fallacy through oversimplification. Any sources you use to utilize to demonstrate the opposing argument should be commensurate in terms of credibility with the sources you use to refute it, if possible. In other words, don’t choose sources to represent the argument that are easy targets or don’t represent the most compelling elements of the opposing argument.

11.3.1.2 Refutation Strategies

The refutation of each opposing argument can either fully rebut the argument or partially concede to it. Strategic concession is important, even in the classical argument, since it shows goodwill, fair-mindedness, and reasonableness on your part. You can use the following strategies to refute qualified arguments:

11.3.1.2.1 Question the Ethos

- The source is not an authority on the subject in question (false authority fallacy).

- The source’s degree of advocacy is excessive. When an author or source champions an idea, the judgement may be clouded by how strongly they agree with their own claim.

- The source clearly is biased in favor of one side, while claiming to be “fair and impartial.”

- The source demonstrably subscribes to an agenda, cosmology, or worldview that clearly compels them to report only on “truths” that support it and ignore or deliberately obscure any others.

- The source does not acknowledge/address opposing or alternative arguments.

- The source is engaging in or routinely engages in ad hominem attacks of individuals with opposing viewpoints, or conversely, routinely praises only those who agree or support their argument.

- The source engages in ad hominem attacks of opposing arguments based on their association with particular organizations, movements, struggles, institutions, political designations, dialects, geographical locations, creeds, ethnicities, etc.

- The source engages in belittling or discrediting any source that disagrees even before they are identifying them (poisoning the well). Example: Anyone who disagrees with my plan is a doubting Thomas.

11.3.1.2.2 Question the Logos

- The testimony and examples can be refuted elsewhere. To counter, provide counter-examples and counter-testimony.

- The evidence is not sufficient to support the claim.

- The sample in the statistics provided is not large enough to be representative (hasty generalization).

- The sample in the statistics provided is not randomly selected, and therefore not representative (hasty generalization).

- The interpretation of the statistics is misleading or spurious. For example, the statistic “77 percent of all accidents happen within 15 miles of the driver’s home” is spurious because, while true, that is where drivers spend most of their time.”

- The argument contains claims that do not follow from their premises (non-sequitur) For example, the Chewbacca Defense: “if Chewbacca lives on Endor, you must acquit” from South Park’s “Chef Aid” episode.

- The argument contains quotes that are misleading or taken out of context (contextomy). For instance, to aver that Charles Darwin said that “Natural selection” is “absurd in the highest degree,” while true, is taken so out of context as to say the direct opposite of what he meant.

11.3.1.2.3 Question the Pathos

- The source contains multiple allusions to unnecessarily stirring or reactionary symbols

- Argument to the People (Stirring Symbol): Just because a popular symbol can create a feeling of solidarity with a group or idea doesn’t necessitate that its use is a good idea.

- The source implicitly or explicitly argues that their argument is valid based only on the number of people who support it (bandwagon fallacy).

- The source

- You can often raise the ire of potential supporters by showing them how an author or article is deliberately trying to play on their compassion or pity to persuade them of a point that would demonstrate more ethos and be more effective when dealt with in objective terms.

11.3.1.2.4 Question the Kairos

11.3.1.2.4.1 Currency of the Topic

Topical currency is almost indecipherable from the false analogy by kairos refutation below, it just applies more generally to the topic of the disputed source or argument. For example, the circumstances of the Vietnam War and Gulf War were enough separated in time that any argument for or against the Gulf War using a source discussing the war in Vietnam might be inappropriate. You can use any significant cultural or technological changes to discredit the older source.

11.3.1.2.4.1 Currency of the Evidence

- The supporting evidence (statistical, testimonial, anecdotal) for the opposing argument is out of date.

- The analogy is no longer relevant. For example, if an argument is attempting to use 1950s gender stereotypes as the basis of an argument against same-sex marriage, this constitutes a false analogy.

- The supporting evidence (statistical, testimonial, anecdotal) for the opposing argument is distant enough in space to be irrelevant.

- The supporting evidence is too far distant in both space and time to be relevant.

An outline for the Alternative/Opposing Arguments section might look like this:

- IV. Opposing Arguments

- A. Opposing Argument A

- a.Summary

- b. Refutation

- i. Counter -evidence

- ii. Counter-argument

- B. Opposing Argument B

- a. Summary

- b. Refutation

- i. Counter-evidence

- ii. Counter-argument

- A. Opposing Argument A

11.3.5 Conclusion

The purpose of the conclusion is to tie everything together, recount the points of your argument, and motivate the audience to act on your conclusions .

Here are some moves you can make in the conclusion:

- Summarize your argument

- Elaborate on the implications of the future

- Offer a call to action.

- Offer a final appeal to pathos to motivate the audience to action.

An outline for the Alternative/Opposing Arguments section might look like this:

- V. Conclusion

- A. Summary

- a.Main point

- b. Secondary point

- c. Tertiary point

- B. Implications

- C. Call to Action

- D. Motivation to Action

- A. Summary

11.4 Rogerian Argument Model

The Rogerian argument, named for its developer, Carl Rogers, is designed to focus on common ground, negotiation, and cooperation rather than opposition, strategic positioning, and competition. While the goals of the classical argument are to sway the audience to your position, the goals of the Rogerian argument are as follows:[2]

- Come to a clear understanding of opposing, conflicting, or alternative solutions

- Accept the relative validity of the audience’s position

- Demonstrate the writer and the audience have similar goals and values, specifically in terms of honesty, integrity, and good will

- To arrive at a mutually acceptable solution

The Rogerian title might include words like exploration, study, possibilities, perspectives, or other non-confrontational words.

Here is a simplified version of the Rogerian argument:

I. Introduction (common ground)

II. Background

III. Alternative Arguments (situations or contexts in which the alternative arguments might be valid)

IV. Lines of Argument (situations or contexts in which the argument you champion is valid)

V. Conclusion (common ground)

There are certainly variations on this version, and this model is simplified to highlight one particular difference between the classical and the Rogerian models, which is that the alternative arguments and lines of argument can switch positions. Both the introduction and the conclusion should focus on the common ground, or the shared values of the author and the audience. This focus on the common ground is ideal for an audience that is highly resistant to your claim, whereas the classical model might work better for audiences that are somewhere in the middle on the scale below:

The delayed thesis and invitational styles of argument are both similar to the Rogerian argument.

11.4.1 Delayed Thesis Style

In the delayed thesis style, the writer waits to present her thesis until she has garnered the trust of the audience.

11.4.2 Invitational Style

The invitational style acknowledges principles of equality, immanent value, and self-determination in rhetoric as being superior to persuasion as a singular goal. It is reasonable to say that in the invitational model there aren’t really any opposing arguments, just alternative perspectives.

11.5 Toulmin Argument

As it is presented here, a Toulmin argument doesn’t really fit in to an outline form and doesn’t prescribe a specific order to follow. Rather, it identifies all the most important elements of the argument and serves as a sort of toolbox full of elements you can plug into either the classical and Rogerian model, depending on your audience and purpose.

11.5.1 Elements in the Toulmin Argument

11.5.1.1 Primary Elements

11.5.1.1.1 Claim

The claim in the Toulmin argument is identical to the claim in section 11.2.3.1.

11.5.1.1.2 Reasons

The reasons in the Toulmin Argument are reasons just like those discussed in section 11.2.3.2, and all are connected to one or more of the four main evidence types: statistical, testimonial, anecdotal, and analogical.

Reasons are also called evidence or data

11.5.1.1.3 Warrant

The warrant consists of beliefs, values, and opinions the audience holds that connect the claim to each reason. In most cases, the warrant isn’t explicitly mentioned in an essay, and the beliefs and values of which it consists are merely presumed.

Example:

You should give an apple to the teacher because, if you do, he will give you a good grade.

- Claim: You should give an apple to the teacher

- Reason: Because he will give you a good grade.

- Warrant:

- Values: Good grades are desirable. Apples are easier to provide than hard work.

- Beliefs: Teachers like apples. Teachers give good grades to students who give them gifts.

- Opinions: The purpose of education is to get good grades so students can appear to be better job candidates to potential employers.

These audience-centered components are discussed at length in Chapter 3 – The Audience.

11.5.1.2 Secondary Elements

11.5.1.2.1 Backing

If the audience doesn’t already hold the beliefs, values, and opinions that are necessary to connect the claim to the reasons, the backing includes additional reasons and evidence that go directly to why the audience should hold these beliefs, values, and opinions. The warrant has the same relationship to the backing as the claim does to the reasons. For example,

- Good grades are desirable because they help students get scholarships.

- You can buy a lot more apples for a few hours spent at a minimum wage job versus the number of hours you would have to commit to homework to get a better grade.

- Ninety percent of teachers report giving better grades to students who give them apples.

11.5.1.2.2 Reservation(s)

The Toulmin element of reservation maps directly to the opposing or alternative argument sections of the classical and Rogerian models.

Other words for reservation: conditions of rebuttal, opposing argument, alternative argument

11.5.1.2.3 Qualification(s)

The qualification or qualifier is an adjustment to the scope of the argument in one way or another. This adjustment should be made with the audience in mind. For instance, if the audience is highly resistant to the idea of deporting all individuals residing illegally in the United States, they would be more amenable to an argument that only those convicted of violent crimes should be deported.

11.5.1.2.3.1 Qualifying words

| Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Frequently | Always |

| None | Few | Some | Many | All |

| Not at all | Hardly | Partially | Mostly | Completely |

11.6 Arrangement Details

The classical and Rogerian models, along with their similar models are more global organizational schemes because they prescribe an order for the essay from start to finish. But there are smaller components of order or arrangement that are just as important to consider once you have mapped out the general course of your project. These include coordination, cohesion, and coherence, and they all contribute to this abstract thing that most people who talk about writing call “flow.” It is a good thing if your essay flows, but it is a bad thing if it doesn’t.

11.6.1 Coordination/Subordination

We can’t talk about coordination without talking about subordination. The two terms go hand in hand and are as follows:

Coordinate elements stand in equal relation to one another.

Subordinate elements are part of or belong to some other thing.

For example, dogs and cats are coordinate elements when considered in relation to one another, but they are both subordinate elements of some other element that includes them both, which in this case could be mammals. If you have read about Aristotle’s system of definition, you should be experiencing a kind of déjà vu right now. This hierarchical designation keeps coming up because it is the way we make sense of the world. More importantly, it is the way language makes sense of the world, and only by attending to hierarchy will you and your essay make sense to others.

Subordinate elements usually supply answers to which questions, and in their simplest terms are prefaced with that. The problem and the gift of language is that we can say that in a million different ways, so we don’t need the thing we are talking about to be present in order to specify which one.

If I tell my neighbor I saw their pet escape from their backyard, they might have to ask which pet. Since the pet is missing, I will have to think of creative ways to say that one, and those creative ways might consist of the cat, or if the neighbor has multiple cats, the white and yellow striped cat. If two cats escaped, then they become coordinate elements, in which case I would have to use a coordinating conjunction to explain that both the white and yellow striped cat and the black cat escaped.

This applies from the lowest component of your essay, the phrase, all the way to the clause, to the sentence, to the paragraph, to the section, to the structure of the essay. The outlines discussed above are a map of the coordinate and subordinate elements. The main headings are coordinate with each other but contain many subordinate elements within them. If your essay is going to “flow,” it has to flow along hierarchical lines, either from the general to the specific or from the specific to the general. Upstream or downstream.

11.6.2 Cohesion

Cohesion and coherence are very closely related. In the simplest terms, cohesion is what makes a text stick together, while coherence is what makes a text make sense. To be cohesive, it must be clear how the that elements of a particular text are related, while to be coherent it must be clear in what ways the how elements of a particular text are related.

In a word, the glue that holds a text together is reference, including self-reference and common external reference. Linguists call references to previous parts of a text anaphoric, references to upcoming parts of the text cataphoric, and references to things outside the text exophoric.

11.6.2.1 References to Previous Parts of the Text (anaphoric reference)

11.6.2.1.1 Stock Words and Phrases

Stock words or phrases are words or phrases that you invent and purposefully repeat throughout the text to bind it together. Some people refer to these as “catchphrases,” and can often help identify a group or a person. One of Homer Simpson’s catchphrases is “Doh,” meaning essentially that something has not gone as planned. One of Bart Simpson’s catchphrases is “I didn’t do it.” Just like these phrases help us identify characters in popular sitcoms, they can help us identify and define the character of a text. One of these phrases that most of us recognize is MLK’s “I have a dream.” Not only is this an example of anaphoric reference and the use of a stock phrase, but it is also a rhetorical device called anaphora, which is essentially the repeated use of anaphoric reference at the beginning of successive sentences or paragraphs. To use this cohesion technique, you can decide on a stock word/phrase or two at the beginning and purposefully use them throughout an essay, or you can see if any start to develop through the writing of it.

11.6.2.1.2 Given-New Contract

The given-new contract is referred to as a contract because meaningful communication is based on an unspoken agreement between writers and readers that the text is going to follow a pattern that bases all new information on something the reader and the writer already both understand. This works on the sentence level, on the paragraph level, and on the section level, and it is one way the reader understands that the text is moving forward. For example, look at the following sentences:

Given-New Order

Comic Book Guy grew up in a house where none of his family members expressed love. When his father, Postage Stamp Fellow, apologized for missing his first baseball game, they hugged for the first time.

Reversed Order

When Comic Book Guy’s father apologized for missing his first baseball game, they hugged for the first time. Comic book Guy grew up in a house where none of his family member’s expressed love.

Both say the same thing, but the given-new order in the first is much more comfortable. The second feels as if we are only being given the critical information after we really needed it, like when someone has to explain a joke after the punch line.

11.6.2.1.2 References to Upcoming Parts of the Text (cataphoric reference)

A cataphoric reference depends on a paired expression later in the text for its meaning. It relates to the rhetorical device cataphora. The structure of cataphora is discouraged in academic writing, but is critical in some fiction and poetry, especially the murder mystery genre. Still, even in academic writing, it helps bind a text together, and if employed skillfully and sparingly, it can be used for rhetorical effect to call attention to a particular sentence or selection, to change focus, to arouse curiosity, and to create suspense.

Here are some examples of cataphoric reference within the sentence.

- A troublesome boy, Bart Simpson, actually saved Springfield when he purposefully vandalized the Springfield Glen Country Club.

- It was a dark day when Burns disguised himself as a worker to spy on his employees.

- If you want them, the donuts are on the counter.

Cataphoric reference isn’t confined to the sentence, however, as you can see from the following example.

- What they saw defied explanation. It was written on a wall, and it was written in an illegible script. It came to be called menetekel.

Cataphoric reference can also be used in a series for rhetorical effect, as in:

- It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s Superman!

- He is annoying. He is loud. He is my brother, Bart.

- He may not be polite. He may not be concise. He may not be politically correct. But he will always be my Grandpa Abe.

11.6.2.1.3 References to Things Outside the Text (Exophoric Reference)

References to additional texts or things that are outside the text also help to hold a text together by further defining its boundaries.

11.6.2.1.3.1 Extrinsic Proof

Outside evidence is essential to an argumentative essay. The classical rhetoricians called it inartistic proof or extrinsic proof, meaning that it is proof that already exists somewhere. It is the task of the argumentative essay to invent some proofs (artistic proofs), but those cannot stand on their own without external evidence like statistics, testimony, and examples.

11.6.2.1.3.2 Demonstrative Pronouns

The common demonstrative pronouns include this, these, that, and those when they refer to objects outside the text.

11.6.2.1.3.2 Limiting Outside References

One way to keep a text cohesive is to repeat particular references to outside sources or objects. For textual or visual sources, this means identifying a few that are central to your argument and using them repeatedly, while using more removed sources only as necessary. There is also such a thing as keeping the scope of your sources too narrow, so this technique is very much dependent on the project you are working on. In the end, you have to trust your thesis to keep the sources you choose in the proper focus.

The outside objects you point to will also be dependent on your project, but these types of references are particularly threatening to cohesiveness. Like the other types of reference, having some builds cohesiveness up to a point, but once that point is exceeded, it all breaks down. Cohesion in language works kind of like cohesion in water. You can fill a glass so full of water that the peak of the bubble that forms at the top is above the sides of the glass. Once you fill it too full, you will break the surface tension, and it will spill over, making the water level with the rim of the glass.

11.6.2.4 Pronouns

Pronouns can have all three types of reference.

11.6.2.4.1 Regular Pronouns

Note that the sentences used previously as examples of the given-new contract can still be confused by reversing the order of the noun-pronoun relationship, which depends critically on the given-new order: the noun, or antecedent, is ordinarily provided before it is replaced with a pronoun. That order can change, but generally it is only changed on rare occasions and for a specific rhetorical purpose.

Consider this:

In this case, the actual noun that the pronoun replaces isn’t known until after the pronoun is encountered, and so it is called the pronoun’s postcedent instead of its antecedent. It is also an example of cataphora or cataphoric reference, discussed below. It works, to be sure, but it has a different feel to it. It makes the reader pause for a moment to sort out who he is. Here is what it looks like on the sentence level, and specifically with pronouns:

- When she arrived at school that morning, Lisa took out her saxophone and played the blues.

- Before he read every page in Lisa’s diary, Bart thought it was all about him.

- After he inserted a quarter into the mysterious nuclear machine, Homer created the Homerverse.

11.6.2.4.2 Relative Pronouns

Relative pronouns, as with other types of pronouns, tend to follow the given-new pattern. When they don’t, relative pronouns call attention to themselves and create the same kind of drama the pronoun does when used before the noun it replaces. The biggest difference is that relative pronouns can span several sentences, whereas the antecedent or postcedent of the pronoun is easier to identify when it is within the boundaries of a single sentence. Not how the relative pronouns in the following sentences span several sentences, bridging ideas that might not otherwise seem connected.

11.6.2.4.1.3 Anaphoric Reference (Pronouns)

11.6.2.4.4 Cataphoric Reference (Pronouns)

11.6.2.4.5 Exophoric Reference

11.6.2 Coherence

Coherence is the thing that makes a piece of writing easy to understand. When we walk away from an essay with the feeling that it made sense, that means it has coherence, that the relationships between elements are clear and explicit. Abe Simpson’s rambling stories that go nowhere, on the other hand, can best be described as incoherent. Some practices that can make an essay more coherent include outlining your essay during the invention phase, which is discussed above. Incorporating parallel structure, Metabasis, and transitional words and phrases also help provide coherence for your argument.

11.6.2.1 Outlining

Someone once said that “behind every great essay is a great outline.” Creating a roadmap, so to speak, of the direction and points of your argument saves you time in the long run and will prevent your meandering away from your thesis statement. Adhering to an underlying structure of an essay, which we often don’t see directly, is what can make the difference between sense and nonsense.

11.6.2.2 Parallel Structure

Use parallel structure to tie coordinate ideas together. In section 10.3.1 you will find an explanation of parallelism in the discussion about using it at a sentence level, but it applies equally to the main ideas of the essay. Take, for instance, the following three supporting reasons for sanctioned street racing on Southwest Terwilliger Boulevard between the hours of two and four in the morning every Sunday:

- Sanctioned street racing will keep participants safer than the illegal street racing that takes place now.

- Sanctioned street racing will create more revenue for businesses in the area.

- Sanctioned street racing will encourage teenagers with cars to perform more frequent maintenance.

So far, the reasons are both coordinate and parallel. They use the same pattern or syntactical structure, and that makes them seem both equal in importance and related to each other. But imagine the same three main points, rendered as follows:

- Sanctioned street racing will keep participants safe.

- Businesses on Terwilliger Street are failing and could use extra revenue, which comes from events like legalized street racing.

- Encouraging teenagers with cars to perform more frequent maintenance is another side effect of legal street racing.

The statements all represent similar ideas, but they do it with different sentence patterns and word forms, so they don’t all seem equal, nor can they be recognized as a family of reasons. There is nothing inherently wrong with these different ways of expressing the same ideas, and it is good to vary sentence patterns generally, but consider using similar patterns to represent the main ideas of your essay, or even secondary ideas down the line. The practice gives the reader some idea of the hierarchical structure and highlights the coordination and subordination that comprises it. It also saves your reader the frustration of trying to determine the relationship between your points. When elements are parallel, readers are better able to make sense of your points.

11.6.2.3 Metabasis

Metabasis is also listed with other rhetorical devices in section !@# Rhetorical Devices. It is essentially a very explicit transition from one major section of an essay to the next. It can be as short as a sentence, but sometimes extends to a paragraph or more, explaining in detail what shift the writer is making and why he is making it. The writer seems to step out of the regular text for a moment and act like a tour guide before jumping back to the main thread again.

11.6.2.4 Transitions

Transitions perform the same function as Metabasis, but in a much less intrusive manner. Implicit transitions use subtle cues like changes in tone, shifts in point of view or tense, adjustments to pacing, and plays on reader expectations to transition without explicitly describing the transition. Direct transitions use specific transitional words or phrases to clue the reader into a transition from one point to another, which often give the reader a sense of the type of transition being made. Implicit transitions are enabled by the strong sense of hierarchical and temporal movement created by a strong outline, making the coherence of the essay less dependent on frequent explicit transitions. We all dread hearing those overused general and bulky ones like “in conclusion,” “Firstly, secondly, lastly,” and “The first point I want to make is.” Use explicit transitions only when necessary, to steer the reader in the right direction, vary the use of these transitions and choose the more specific over the general. The comprehensive list below can be used to find just the right transitional word or phrase.

11.6.2.4.1 Implicit Transitions

11.6.2.4.1.1 Tone

Shifts from a more formal to a less formal tone might signal a transition between hard evidence or reasoning to more testimonial or anecdotal evidence, and vice versa.

11.6.2.4.1.2 Point of View

A shift from third person to first person point of view indicates the introduction of personal experience or other empirical narrative, and the shift back to third person indicates a transition back to more objective evidence.

11.6.2.4.1.3 Tense

While it is important for the purposes of cohesion to maintain a consistent tense throughout your essay, you may need to invoke the past tense when discussing historical evidence or events. You may also need to use the tense future when discussing implications.

11.6.2.4.1.4 Mood

A switch in the mood of your verbs can also be a highly effective implicit transitional device. Verb moods don’t convey emotion. Verb mood refers to the quality or form of the verb and allows the writer to make their intention clear through the denotative tone of the verb.

The verb moods are as follows:

Indicative indicates a statement of fact, at least according to the writer or speaker.

Imperative refers to a request or a command.

Subjunctive is used when the writer or speaker refers to doubtful, hypothetical, wishful, or not factual situations.

Conditional verbs explain that one action is dependent on another and are accompanied by auxillary verb, which are also known as linking or helping verbs.

Interrogative verbs invoke a question and usually employ auxiliary verbs.

11.6.2.4.1.5 Pacing

Changing the length and structure of your sentences can signal a transition. For example, a short, simple sentence often signals the end of one line of thinking and prepares the audience for another.

11.6.2.4.1.6 Audience Expectations

Because of the way language works, the audience has some expectation of what things are likely to come next. The underlying organization of your paper should reveal a clear path, so signposts are not always necessary. The order of the paper, in other words, should already make some sense to the audience, in the same way that they know that an appetizer is usually followed by dinner which is usually followed by dessert, and so forth. It is when something is tangential or comes out of a conventional order that signposting becomes necessary. Think of the last good movie you watched and recall whether you got the sense by the introduction, buildup, climax, and resolution that it was coming to a close. It isn’t usually necessary for a good movie to announce its conclusion, and the same holds true for a well-written essay.

11.6.2.4.1.7 Movement

Movement has much to do with audience expectations. If the audience has successfully boarded your train of thought, then they have enough of an idea about what comes next, and you don’t necessarily have to announce every little stop along the way. The trick here is to create movement by using recognizable patterns of argument and organization to get things moving and keep them moving.

11.6.2.4.2 Explicit Transitions

Explicit transitions signal to the audience that you are moving from one concept to another, but they do it in a way that gives them a sense of the type of transition being made, whether it is from a higher level to a subordinate level, from an earlier time to a later time, from one place to another, from cause to effect, or something similar. See the types of transitions below for examples.

11.6.2.4.2.1 Transitional Words And Phrases

Transitional words and phrases are typically subdivided according to the types of relationship they identify or the purpose they serve. Typically, categories include conclusion, summary, comparison, contrast, causality, and support. In keeping with the rhetorical framework of this handbook, they are here subdivided according to Aristotle’s ten categories: substance, quantity, quality, relative, where, when, being-in-a-position, having, doing, and being affected.

11.6.2.4.2.1.1 Substance – Relationships defined by their position in a hierarchy of universals and particulars

Some purposes of this type of transition include to subordinate, to classify, to provide examples, and to define.

| as an illustration | for example | in detail | namely | including |

| e.g. (“for example” | for instance | in general | particularly | to illustrate |

| evidently | illustrated by | in particular | specifically | to demonstrate |

| explicitly | in any case | in the case of | such as | in this case |

| expressly | in any event |

11.6.2.4.2.1.2 Quantity – Relationships defined by differences in quantity

Some purposes of this type of transition include to add, to subtract, to include, to exclude, to compare, to group together, and to ungroup.

| additionally | as well as | i.e. (“that is”) | moreover | to enumerate |

| all in all | besides | in a word | nor | to point out |

| all things considered | beyond | in addition | not only … but also | to put it differently |

| also | coupled with | in brief | not to mention | to rephrase it |

| altogether | even more | in conclusion | on the whole | to say nothing of |

| an often overlooked point | even more so | in other words | only | to sum up |

| and | for the most part | in short | summing up | to summarize |

| another key point | further | in sum | surprisingly | together with |

| as a matter of fact | furthermore | in summary | that is | too |

| as can be seen | generally speaking | in the end | that is to say | what’s more |

| as much as | given these points | indeed | to conclude |

11.6.2.4.2.1.3 Quality – Relationships defined by differences in qualities

Some purposes of this type of transition include to compare, to contrast, to agree, and to disagree.

| albeit | in accordance with | otherwise | another key point | in the end |

| although | in contrast | overall | as a matter of fact | indeed |

| although this may be true | in either case | point often overlooked | as can be seen | moreover |

| and yet | in like manner | positively | as much as | nor |

| as | in similar fashion | rather | as well as | not only … but also |

| as compared to | in spite of | regardless | besides | not to mention |

| at the same time | in the same fashion / way | similarly | beyond | on the whole |

| be that as it may | in the same way | telling | coupled with | only |

| but | instead | though | even more | summing up |

| by the same token | it is true | to be sure | even more so | surprisingly |

| certainly | like | truly | for the most part | that is |

| comparatively | likewise | uniquely | further | that is to say |

| compared to | nevertheless | unless | furthermore | to conclude |

| conversely | nonetheless | unlike | generally speaking | to conclude |

| correspondingly | not | whereas | given these points | to enumerate |

| despite | notably | yet | i.e (“that is”) | to point out |

| different from | notwithstanding | additionally | in a word | to put it differently |

| equally | of course …, but | all in all | in addition | to rephrase it |

| even so | on balance | all things considered | in brief | to say nothing of |

| even though | on the contrary | also | in conclusion | to sum up |

| for one thing | on the negative side | altogether | in other words | to summarize |

| granted | on the other hand | an often overlooked point | in short | together with |

| granted that | on the positive side | and | in sum | too |

| however | opposite to | in summary | what’s more | |

| identically | or |

11.6.2.4.2.1.4 Relative – Relationships defined by differences in matters of degree, like size, magnitude, or importance.

Some purposes of this type of transition include to rank, to order, and to emphasize. Unlike transitions of substance, they do not rank in terms of generality or specificity, but of gradations.

| above all | critically | foundationally | surely | must be remembered |

| absolutely | definitely | important to realize | especially | of less importance |

| centrally | equally important | to emphasize | most compelling evidence | primarily |

| chiefly | most importantly | most importantly | significantly | of equal importance |

11.6.2.4.2.1.5 Where – Relationships defined by differences in location

Some purposes of this type of transition include to place, to juxtapose, and to position.

| about | below | neighboring on | to | wherever |

| above | here | peripherally | where | there |

| adjacent to | nearby |

11.6.2.4.2.1.6 When – Relationships defined by differences in time or sequence

Some purposes of this type of transition include to differentiate between past, present, and future, to predict, to enumerate, and to order things of equal importance.

| again | finally | in the first place | putting it differently | to begin with | ||

| all of a sudden | first | in the hope that | quickly | to clarify | ||

| always | first thing to remember | in the light of | seeing that | to put it another way | ||

| and then | first, second, third | in the long run | simultaneously | to repeat | ||

| as has been noted | firstly | in the meantime | so far | ultimately | ||

| as I have noted | following | in the second place | sometimes | until | ||

| as I have said | forever | in view of | soon | until now | ||

| as I have shown | forthwith | last | sooner or later | up to the present time | ||

| as shown above | frequently | lastly | still | usually | ||

| at length | from time to time | later | subsequently | when | ||

| at the present time | henceforth | meanwhile | then | whenever | ||

| at this instant | immediately | never | then again | while | ||

| before | in a moment | next | thereupon | with this in mind | ||

| during | in due time | now | this time | without delay | ||

| earlier | in the final analysis | once | till |

11.6.2.4.2.1.7 Being-in-a-position – Relationships defined by posture or stance

Some purposes of this type of transition include to switch to a different attitude or stance, to explain, to attack, to defend, to concede, to qualify, to affirm, and to deny.

| to explain | undeniably | unquestionably | with attention to | with certainty |

| with this intention | without a doubt |

11.6.2.4.2.1.8 Having – Relationships defined by differences in characteristics or items that properly belong to each element.

Some purposes of this type of transition include to acknowledge, to identify, to associate, and to disassociate.

| in essence | in fact | in reality | naturally | obviously |

| of course | ordinarily |

11.6.2.4.2.1.9 Doing/Being Affected – Relationships defined by a cause/effect relationship

Some purposes of this type of transition are to establish causality, to identify causes, to identify effects, to prove, to solve, to predict, and posit.

| accordingly | because the | in the event that | since | for the same reason |

| and so | consequently | inasmuch as | so as to | for this reason |

| so long as | due to | lest | so that | given that |

| as a result | even if | on the condition that | therefore | hence |

| as long as | for | on account of | thus | if…then |

| as soon as | for fear that | owing to | to the end that | in effect |

| because | for that reason | points towards | in order to | in that case |

| because of | for the purpose of | provided that | so that | therefore |

| since | so as to | thus | to the end that |

Having the same measure; of equal extent, duration, or magnitude; coextensive.

full of concentrated meaning; conveying meaning forcibly through brevity of expression (OED)