Houses of Rhetoric

The Five Houses of Rhetoric

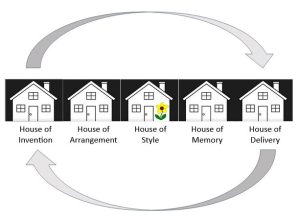

It was Cicero, a Roman statesman and orator, who first clearly identified the five cannons of rhetoric somewhere around 90 BC in a book he called On Invention, where “invention” also happens to be the first of these “cannons” he speaks of. Okay, truthfully, he never uses the word “cannon.” When we use the word canon we mean it in the sense of a fundamental axiom or tenet. And while it is more fun to call these fundamental axioms or tenets of rhetoric cannons, because using them effectively is similar to firing ideological cannonballs of persuasion at nonsense and obscurity (This, we will see, is debatable, since some have rightfully pointed out that rhetoric can just as easily be used to cover up truth and spread nonsense, just as cannons can be used to attack or defend something), I would rather use the term “houses,” and here is why:

Because houses can contain things, and it is important for us to remember as we go forward that the principles that we have discussed previously, like rhetor, purpose, audience, ethos, pathos, logos, and kairos, can inhabit these general domains, called invention, arrangement, style, memory, and delivery. Since, as we will see in the chapter on style, choosing the right metaphor can make all the difference, let’s think of these as houses, and the collection of them as the rhetorical neighborhood. This will allow us to attribute meaning to various conjunctions like ethos in the house of memory, or logos in the house of style, kind of like astrologers attribute meaning to the positions of the planets among the stars according to their mythological character, like “when the moon is in the seventh house, and Jupiter aligns with Mars.”[1]

The First House ~ Invention

Invention refers to the process of deciding upon a topic to write about. Brainstorming is one method of coming up with something to say about a given topic, but invention doesn’t end there. Once a writer things of everything that could be said about a topic, she must work to identify what has already been said, and how to use it to work toward an original angle or topic, working from the known to the unknown.

The Second House ~ Arrangement

Choosing the best and most persuasive order of presentation. Sometimes referred to as organization. Using a logical order of progression combined with implicit and explicit transitions that move the reader effortlessly to the conclusion. One rule of thumb that involves the persuasive appeals we discussed earlier is that ethos could be employed in the beginning of an essay to establish credibility, logos in the middle to delineate the reasoning and provide evidence, and pathos in the end to spur the reader to action.

The Third House ~ Style

Grammatical Competence

Grammatical competence consists of an awareness of and ability to write grammatically “correct” sentences. The word correct is enclosed in care quotes because multiple grammars exist, and what is correct in one may not be correct in the other. Academic writing generally follows the conventions of American Standard English Grammar, which is described in detail in the Little Seagull Handbook.

Lexical Competence

Lexical competence is the ability to choose the best words for the situation and arrange them in the most effective order. Having a lot of words to choose from and a familiarity with a variety of word constructions lends to this ability. Reading a lot is a great way to get this familiarity.

Rhetorical Competence

Rhetorical Competence could be conceived of as the ability to combine a mastery of the first two categories to achieve powerful effects. An understanding and familiarity with rhetorical devices, schemes, and tropes is critical here, and again can be gained through reading extensively. Interestingly, many of the rhetorical devices depend on intentionally breaking the rules of grammar to achieve their desired effect.

The Fourth House ~ Memory

Think of memory as a looking back to the past.

Intertextuality:

An awareness of what is known about a particular topic and who said it. A detailed understanding of all sides of an argument or issue. Choosing sources carefully, making detailed notes on them, and taking care to document them properly.

Proofreading:

Rereading and correcting superficial issues like typos, misspellings, fused sentences, comma splices, missing words, confused words, etc. Rereading forwards, backwards, sideways, and out loud to correct those little details where the devil is.

Revision:

Re-imagining and rewriting your work to make it more effective.

Reflection:

Reflecting on your successes and failures for everything one writes – making the successes habits and the failures history.

The Fifth House ~ Delivery

The authors of Ancient Rhetorics for Contemporary Students, Sharon Crowley and Deborah Hawhee, suggest that delivery is all about “attending to the eyes and ears” (325). Because early rhetoric was developed in a primarily oral culture, delivery could mean something similar to elocution or other performative aspects of speech. For instance, pausing at just the right moment, in a speech, could have a dramatic effect. But how does one pause in writing? Crowley and Hawhee argue that punctuation was developed to indicate various types of vocal pauses in writing, so in their conception the use of basic mechanics and punctuation like commas, periods, headings, and even paragraph divisions are in some sense an element of delivery. They go so far as to suggest that a writer should read a paper out loud and look for natural pauses as opportunities for punctuation. Note that “rhetorical competence,” discussed above, often involves leaving commas or other punctuation out where traditional grammarians say they belong in order to achieve a certain effect. So if we think of delivery as attending to the ear in writing, there seems to be some overlap between style, memory, and delivery.

For our purposes it might be easier to think of delivery in writing as attending to the eye. In other words, how does the essay or other writing project look. In this sense, delivery is as superficial as judging the character of a person simply by the way they look or dress. And as superficial as that is, it happens all the time in both face to face encounters and in writing. You will find, more than likely, that you have already passed judgement on a piece of writing before you have ever read a single word, just by the way it appears. In this sense delivery is more focused on format than any of the other canons of rhetoric, so when you think delivery think formatting, typefaces, page layout, headings, type styles, white space, paragraph divisions, line spacing, and image placement.

The Rhetorical Neighborhood

In keeping with the residential metaphor, all of rhetoric represent all of rhetoric as a kind of neighborhood – a virtual neighborhood – where all the most important concepts reside. Ethos, pathos, logos, and kairos all travel throughout the neighborhood, occupying or visiting various houses at different times, resulting, as mentioned above, in various meanings depending on who is visiting or occupying what house, and on what occasion. I think it is most useful to imagine that theses houses are arranged on a cul-de-sac, with the House of Invention and the House of Delivery at the entrance, and the others kind of completing the semi-circle. The reason for such a conception is that while these two houses represent in some way the entrance and exit points of a particular rhetorical project, and the

rest are treated in sequential order from Invention to Delivery, they are rarely visited sequentially by the rhetor, and are rather recursive: that is, as a rhetor, you will visit each of the houses throughout the process at different times and in a different order. You may be working in the House of Memory and then suddenly find yourself in the House of Invention again, stopping by the House of Style before returning again to the House of Memory.

Let me now tell you the story my friend, who once lived on a cul-de-sac, recently told me. A favorite pastime [link here to pastime/pass time] of the kids in the neighborhood was to play baseball in the circle framed there by their houses. The pitcher would stand in the center, and then the bases were somewhat defined by whichever driveway or walkway they most aligned with, so that first base might have been at Billy’s mailbox, second base – well it would have been in the middle of the street, and third base at the entrance to Francesca’s walkway to her front door. Now it just so happened that home plate lined up with Jeff’s driveway in the center of the cul-de-sac, so that when one day when he was on second base and his teammate hit one into the outfield (in this case the street beyond, he ran as fast as he could for third, wondering if he was doing the right thing. As he neared third everyone in the neighborhood was cheering him “Go home Jeff, Go home!” Thinking he had done something terribly wrong and was being ejected from the game, he ran past home plate, down his walkway, up his front steps, through his front door, and inside his “home,” tears in his eyes. He went home, as they all had asked, but it really was not the “home” his teammates were hoping for.

This is, of course, the type of misunderstanding we hope to avoid through rhetoric.

With that said, you may find that you have a favorite house, where you most like to spend your time, and could regard as something of a home. For me, it is the House of Memory, so whenever I feel like I am lacking productivity, I return to the house of memory and start reading what other people have written. I call that my home. Also, it may become clear that certain elements are more at home in some houses than others, like kairos, or good timing, is probably most at home in the House of Arrangement. You may find you have a home in one or the other houses of rhetoric as well.

- The 5th Dimension, "Age of Aquarius" ↵