The Court System

Every state has two court systems: the federal court system, which is the same in all fifty states, and the state court system, which varies slightly in each state. Federal courts are fewer in number than state courts. Because of the Tenth Amendment, discussed earlier, most laws are state laws and therefore most legal disputes go through the state court system.

Federal courts are exclusive; they adjudicate only federal matters. This means that a case can go through the federal court system only if it is based on a federal statute or the federal Constitution. One exception is called diversity of citizenship. See 28 U.S.C. § 1332. If citizens from different states are involved in a civil lawsuit and the amount in controversy exceeds $75,000, the lawsuit can take place in federal court. All federal criminal prosecutions take place in federal courts.

State courts are nonexclusive; they can adjudicate state or federal matters. Thus an individual who wants to sue civilly for a federal matter has the option of proceeding in state or federal court. In addition, someone involved in a lawsuit based on a federal statute or the federal Constitution can remove a lawsuit filed in state court to federal court. See 28 U.S.C. § 1441. All state criminal prosecutions take place in state courts.

Jurisdiction

Determining which court is appropriate for a particular lawsuit depends on the concept of jurisdiction. Jurisdiction has two meanings. A court’s jurisdiction is the power or authority to hear and decide the case. If a court does not have jurisdiction, it cannot hear the case. Jurisdiction can also be a geographic area over which the court’s authority extends.

There are two prominent types of court jurisdiction. Original jurisdiction means that the court has the power to hear a trial. Usually, only one opportunity exists for a trial, although some actions result in both a criminal and a civil trial. During the trial, evidence is presented to a trier of fact, which can be either a judge or a jury. The trier of fact determines the facts of a dispute and decides which party prevails at trial by applying the law to those facts.

Once the trial has concluded, the next step is an appeal. During an appeal, no evidence is presented; the appellate court simply reviews what took place at trial and determines whether or not any major errors occurred. The power to hear an appeal is called appellate jurisdiction. Courts that have appellate jurisdiction review the trial record for error. The trial record includes a court reporter’s transcript, which is typed notes of the words spoken during the trial and pretrial hearings. In general, with exceptions, appellate courts cannot review a trial record until the trial has ended with a final judgment. Once the appellate court has made its review, it has the ability to take three actions. If it finds no compelling or prejudicial errors, it can affirm the judgment of the trial court, which means that the judgment remains the same. If it finds a significant error, it can reverse the judgment of the trial court, which means that the judgment becomes the opposite (the winner loses, the loser wins). It can also remand, which means sending the case back to the trial court, with instructions. After remand, the trial court can take action that the appellate court cannot, such as adjusting a sentence or ordering a new trial.

Some courts have only original jurisdiction, but most courts have a little of both original and appellate jurisdiction. The US Supreme Court, for example, is primarily an appellate court with appellate jurisdiction. However, it also has original jurisdiction in some cases, as stated in the Constitution, Article III, § 2, clause 2: “In all Cases affecting Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, and those in which a State shall be Party, the supreme Court shall have original Jurisdiction. In all the other Cases before mentioned, the supreme Court shall have appellate jurisdiction.”

Example of Original and Appellate Jurisdiction

Don is prosecuted for the attempted murder of Victoria. Don is represented by public defender Sam. At Don’s trial, despite Sam’s objections, the judge rules that Don’s polygraph examination results are admissible, but prohibits the admission of certain witness testimony. Don is found guilty and appeals, based on the judge’s evidentiary rulings. While Sam is writing the appellate brief, he discovers a 2019 Alaska Supreme Court case that bars the admission of polygraph examination results. Sam can include the case precedent in his appellate brief. The appellate court has the jurisdiction to hold that the objection was improperly overruled by the trial court, but is limited to reviewing the trial record for error. The appellate court lacks the jurisdiction to admit new evidence not included in the trial record.

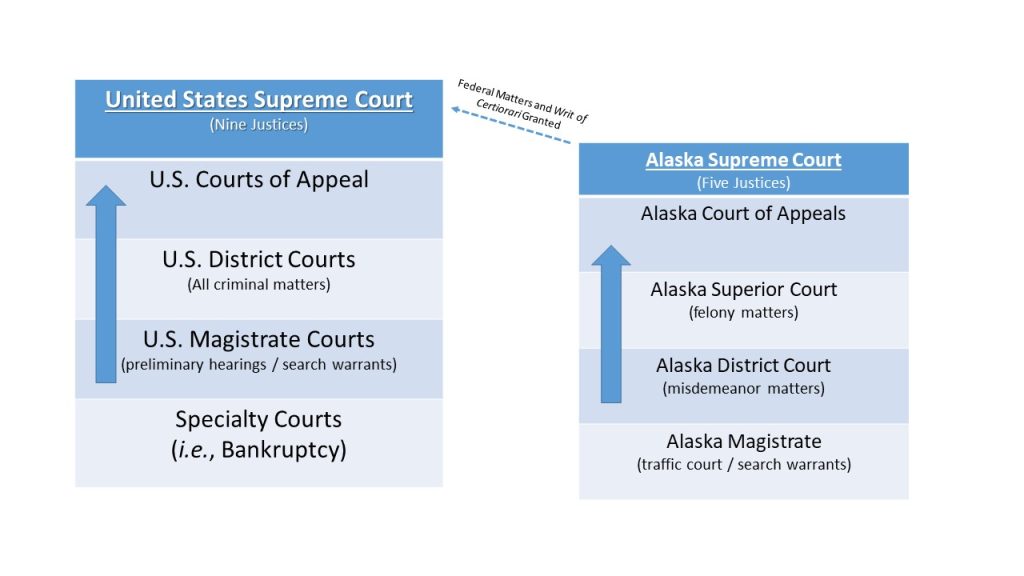

The Federal Courts

For the purpose of this book, the focus is the federal trial court and the intermediate and highest level appellate courts because these courts are most frequently encountered in a criminal prosecution. Other federal specialty courts do exist but are not discussed, such as bankruptcy court, tax court, and the court of military appeals.

The federal trial court is called the United States District Court. Large states like California have more than one district court, while smaller states may have only one. Alaska has one district: The District of Alaska. District courts hear all the federal trials, including civil and criminal trials. As stated previously, a dispute that involves only state law, or a state criminal trial, cannot proceed in federal district court. The exception to this rule is the diversity of citizenship exception for civil lawsuits.

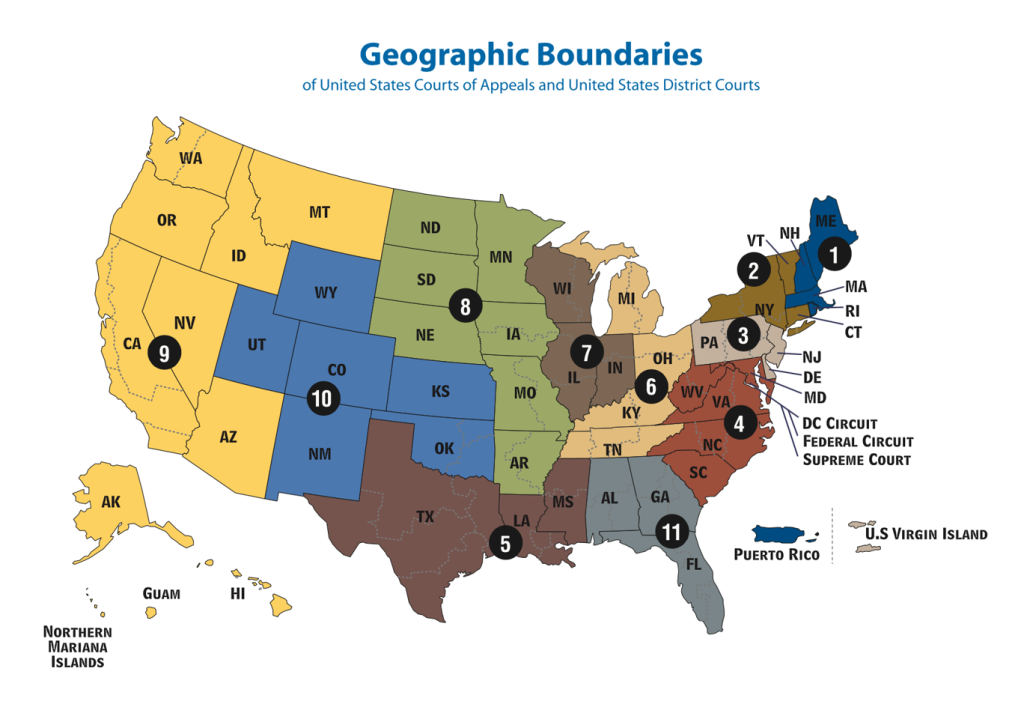

After a trial in district court, the loser gets one appeal of right. This means that the intermediate appellate federal court must hear an appeal of the district court trial if there are sufficient grounds. The intermediate appellate court in the federal system is the United States Court of Appeals. Only thirteen US Courts of Appeals exist for all fifty states. The US Courts of Appeals are spread out over thirteen judicial circuits and are also referred to as Circuit Courts. Alaska is in the Ninth Circuit.

Figure 1.8 – Geographic Boundaries of the United States Courts of Appeals

Circuit Courts have appellate jurisdiction and can review the district court criminal and civil trials for error. The Circuit Court reviews only trials that are federal in nature, except for civil lawsuits brought to the district court under diversity of citizenship. Also, in general, only a defendant found guilty may appeal a verdict; the government may not appeal an acquittal (also called a “not-guilty” verdict), as this would violate a defendant’s double jeopardy protection.

After a Circuit Court appeal, the loser has one more opportunity to appeal to the highest-level federal appellate court, which is the United States Supreme Court. The US Supreme Court is the highest court in the country and is located in Washington, DC, the nation’s capital. The US Supreme Court has eight associate justices and one chief justice.

The US Supreme Court is a discretionary court, meaning it does not have to hear appeals. Unlike the Circuit Courts, the US Supreme Court can pick and choose which appeals it wants to review. The method of applying for review with the US Supreme Court is called a petition for a writ of certiorari.

The loser in any case from a Circuit Court, or a case with a federal matter at issue from a state’s highest-level appellate court, can petition for a writ of certiorari. If the writ is granted, the US Supreme Court reviews the case. If the writ is denied, which it is the majority of the time, the ruling of the Circuit Court or state high court is the final ruling. For this reason, the US Supreme Court reverses many cases that are accepted for review. If the US Supreme Court wants to “affirm” the intermediate appellate court ruling, all it has to do is deny the petition and let the lower court ruling stand.

The State Courts

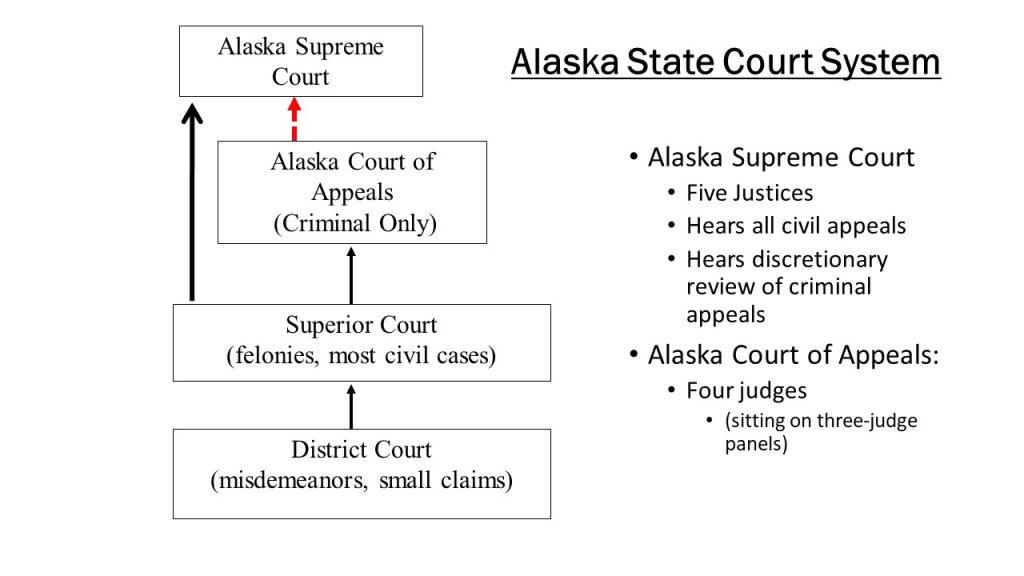

For the purpose of this section, the Alaska state court system is reviewed. Slight variations in this system may occur from state to state.

In Alaska, most criminal matters begin in the Alaska District Court, which is a court of limited jurisdiction. Alaska District Court has jurisdiction to hear misdemeanor criminal offenses and hold first appearances and preliminary hearings in felony cases. A preliminary hearing is a procedure where the prosecutor must establish that there is probable cause to warrant charging a person with a felony. A preliminary hearing occurs in open court before a judge. The accused is present, and the witnesses are subject to cross-examination. A preliminary hearing is different than a grand jury. Alaska District Court cannot adjudicate felony criminal matters or family court matters such as granting a petition for divorce. It also may not hear civil claims that exceed $100,000 in damages. Alaska District Court also hears small claims matters, which is a civil court designed to provide state citizens with a low-cost option to resolve disputes where the amount of controversy is minimal. A traditional small claims court only has the jurisdiction to award money damages. The amount in dispute must be less than $10,000. Small claims court, sometimes called “people’s court,” is intentionally informal, and a person need not hire an attorney to appear in small claims court. It has special rules that make it amenable to the average individual. Small claims court appeals are the exception to the general rule and when the appeal is granted, it usually results in a new trial where evidence is accepted.

Alaska’s court of general jurisdiction is the Alaska Superior Court. Superior Court judges have the authority to hear all civil litigation matters, all state criminal matters, and nonlitigation cases, including family law, wills and probate, foreclosures, and juvenile adjudications. Once a defendant in a felony criminal case is indicted by the grand jury, the Superior Court has exclusive jurisdiction. A grand jury is a secret hearing held at the request of the prosecutor, that listens to the preliminary evidence against a defendant and decides if there is sufficient evidence to warrant the case going to trial (sometimes referred to as a probable cause finding). See generally Alaska Criminal Rule 6. The grand jury is conducted without the presence of the judge, defense attorney, or defendant. Witnesses are not subject to cross-examination. The grand jury is generally made up of 18 citizens, a majority of whom have to agree that the evidence is sufficient to warrant an indictment. An indictment is the formal charging document outlining the specific criminal laws the defendant is accused of violating. Remember that an indictment is merely an accusation of criminality. A defendant is presumed innocent until a petit jury (i.e., traditional trial jury) finds the accused guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

The intermediate appellate court for Alaska is called the Alaska Court of Appeals. The Alaska Court of Appeals only has jurisdiction over criminal matters. It may not hear any cases involving a civil appeal. The Alaska Court of Appeals provides appellate review as a matter of right, meaning it must hear an appeal coming from the state’s trial court. Only a defendant found guilty can appeal without violating the protection against double jeopardy. At the appellate level, the Court of Appeals simply reviews the trial court record for error and does not have the jurisdiction to hear new trials or accept evidence.

The highest appellate court for the state is the Alaska Supreme Court. The supreme court is a mandatory appellate court for civil matters and a discretionary court on criminal matters. In this vein, in criminal cases it gets to select the appeals it hears, very similar to the US Supreme Court. The supreme court generally grants a petition for hearing if it decides to hear a criminal case coming out of the Court of Appeals. If review is denied, the Court of Appeals ruling is the final ruling on the case. If review is granted and the supreme court rules on the case, the loser has one more chance to appeal, if there is a federal matter, to the US Supreme Court.

Figure 1.9 Diagram of the Court System

Figure 1.10 Diagram of Federal and State Court System.