Competency and Insanity

This chapter provides a brief overview of various criminal defenses based on excuse, including defenses related to mental illness. Remember that excuse defenses focus on the defendant. A defendant is not claiming they were justified in their actions, but that they should not be held responsible for their actions because circumstances prevented them from acting lawfully. Excuse defenses are perfect defenses and are affirmative defenses in many situations.

Mental Illness

It is well known that mental illness plays a large role in the criminal justice system. By most accounts, correctional institutions (i.e., prisons and jails) account for the largest percentage of mental health providers in the country. Alaska is no different. On any given day, 65% of Alaska inmates suffer from mental illness or Substance Use Disorder (SUD). See Hornby Zeller Associates, Inc., Trust Beneficiaries in Alaska’s Department of Corrections (May 2014). The law has long recognized that a person who suffers from a serious mental illness may be treated differently in the criminal justice system. A person’s mental illness frequently influences how the government proceeds with a criminal prosecution, such as preventing a person from standing trial (competency), relieving a person from criminal responsibility (insanity), or resulting in punishment despite their mental illness (GBMI).

Not all mental illnesses affect culpability. Only a person suffering from a mental disease or defect may rely on an excuse defense. AS 12.47.130(5). A mental disease or defect means a disorder of thought or mood that substantially impairs a person’s ability to cope with the ordinary demands of life. Mental diseases or defects are not limited to psychological disorders, but include mental disabilities caused by traumatic brain injury or other intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Competency

To understand the defense of insanity, one must first understand, and differentiate it from, competency. Competency refers to a person’s cognitive ability to stand trial. Competency requires a defendant to understand the proceedings against him and be able to assist in his own defense. If a defendant is incompetent as a result of a mental disease or defect, the defendant may not be tried, convicted, or sentenced for a criminal offense. AS 12.47.100. Competency is a constitutional barrier to criminal charges. Competency is not a defense to criminal behavior. Instead, a criminal defendant has a constitutional due process right to understand the nature of the proceedings against him. It is fundamentally unfair to punish a person who does not understand the actions being taken against him. A defendant must have a rational and factual understanding of the proceeding against him and have sufficient present ability to communicate with his lawyer with a reasonable degree of rational understanding. See Dusky v. United States, 362 U.S. 402 (1960). Note however, the Constitution only requires a minimal level of competency. The defendant need not be able to articulate the nuances of criminal law or the nature of the proceedings against him. The law only requires a basic understanding of the system and the accusations.

Competency refers to the defendant’s condition at the time of the court proceeding, not at the time of the offense. Competency is a fluid concept; it is not static. A person’s competency can change throughout a court proceeding. Although a person’s incompetence must be caused by a mental disease or defect, the question of competency is a legal question, not necessarily a medical question. Although medical opinions inform a judge in determining a person’s competency, the ultimate decision rests with the court and not medical professionals. Criminal defendants are presumed competent. The party challenging competency has the burden to prove the defendant’s incompetence.

Gamble v. State, 334 P.3d 714 (Alaska App. 2014)

In the following case, the court is faced with the question of how much weight to give a defendant’s attorney’s opinion about the defendant’s competency. Notice how the trial court describes the defendant’s understanding of the court process and how this informed its final decision on competency.

334 P.3d 714

Court of Appeals of Alaska.

Johnnie J. GAMBLE, Appellant,

v.

STATE of Alaska, Appellee.

No. A–11042.

Sept. 19, 2014.

OPINION

ALLARD, Judge.

After being charged with three counts of violating a domestic violence protective order, Johnnie J. Gamble was found incompetent to stand trial and committed to the Alaska Psychiatric Institute (API) for 90 days in an effort to restore him to competency. At the end of the 90–day commitment, the trial court concluded that Gamble was competent to proceed to trial, despite his attorney’s continuing objections that Gamble could not meaningfully participate in his own defense. Gamble was subsequently convicted of two counts of violating a protective order.

Gamble appeals, arguing that the trial court erred in finding that he was competent to stand trial. For the reasons explained in this opinion, we affirm the trial court’s ruling.

Facts and proceedings

The State charged Gamble in two separate cases with three counts of violating a domestic violence protective order. Shortly after Gamble’s arraignment, Gamble’s attorney requested a competency evaluation of Gamble to determine if he was legally competent to stand trial.

Dr. Lois Michaud, a forensic psychologist at API, conducted a competency evaluation of Gamble on January 19, 2011. Dr. Michaud reported that Gamble was very delusional and would be unable to consult with his attorney in a rational manner or present a rational defense. She observed that Gamble’s delusions included his belief that he had already been to trial and that he needed to talk to a physicist because, in his words, “the theory of causality, cause and effect, everything is created by God and every physical thing possibly has already happened and can happen again.” Dr. Michaud concluded based on the intensity and intrusiveness of Gamble’s delusions that he was not competent to stand trial.

Superior Court Judge [George], found Gamble incompetent to stand trial. Pursuant to AS 12.47.110(a), Judge George then ordered Gamble committed to API for 90 days for further evaluation and possible restoration to competency.

Near the end of the 90 days, Dr. Michaud re-evaluated Gamble and concluded that his mental condition had improved under the structured setting of the psychiatric hospital and that he was now competent to stand trial. At the subsequent competency hearing, Dr. Michaud testified that when she first interviewed Gamble in January, his delusional ramblings and the intrusiveness of his delusional thoughts made him very difficult to interview. Gamble had greatly improved by the time he was re-evaluated, and his delusions were significantly “less intrusive” than before. Dr. Michaud concluded that while Gamble’s delusions had not entirely disappeared, they no longer presented the same barrier to coherent and rational communication as before.

However, Dr. Michaud specifically warned the court and the parties that exposure to an unstructured environment (like jail or trial) could cause Gamble’s delusions to become more intrusive, and that Gamble’s attorney “would be the first to know” if Gamble began to experience the type of active delusions that would render him incompetent.

Gamble’s attorney disagreed with Dr. Michaud’s conclusion that Gamble was competent to stand trial. The attorney argued that the nature of Gamble’s delusions—his belief that everything happens in a loop, and that everything has happened before, including his trial—meant that Gamble was unable to effectively assist in his own defense, and that his case should therefore be dismissed[.]

Judge George concluded that the mere existence of Gamble’s delusions, standing alone, did not necessarily prevent him from communicating with a reasonable degree of rational understanding with his attorney or otherwise prevent him from meeting the standard for competency. After observing Gamble’s demeanor at the second competency hearing, the court found that Gamble was doing better and that he was not in one of his “more agitated states.” The court further found that Gamble “appreciate[d] the nature of the proceedings,” understood the role of the parties and court, and was able to speak and convey thoughts to his attorney, including his various disagreements with his attorney’s litigation strategy. The court therefore found Gamble competent to stand trial[.]

[…]

The case then went to trial. The jury convicted Gamble of two counts of violating a protective order and acquitted him of the third count.

This appeal followed.

Did the trial court err in finding Gamble competent to stand trial?

Under Alaska law, a defendant is incompetent to stand trial if, as a result of a mental disease or defect, the defendant is “unable to understand the proceedings against the defendant or to assist in the defendant’s own defense.” This standard necessarily incorporates the federal constitutional standard for competency to stand trial, which requires a defendant to have a rational and factual understanding of the proceedings against him and to have a sufficient present ability to consult with his lawyer with a reasonable degree of rational understanding.

A defendant who is incompetent to stand trial may not be tried, convicted, or sentenced for the commission of a crime so long as the incompetency exists. The conviction of a defendant who is not competent to stand trial violates due process of law.

Because the integrity of the judicial proceeding is at stake when the competency of a criminal defendant is in question, a trial court has a duty to order a competency evaluation whenever there is good cause to believe that the defendant may be incompetent to stand trial. Additionally, because a defendant’s mental state may deteriorate under the pressures of incarceration or trial, a trial court is required to be responsive to competency concerns throughout the criminal proceeding.

In the current case, Gamble does not dispute the trial court’s finding on the first prong of the competency standard. That is, Gamble does not dispute that he understood the proceedings against him. Instead, his challenge is exclusively to the second prong of the competency test—whether he could participate in his own defense and consult with his lawyer with a reasonable degree of rational understanding.

Gamble asserts on appeal, as he did below, that the nature of his delusional beliefs—which made him believe that everything had already happened—prevented him from being able to assist in his defense or communicate with his attorney with a reasonable degree of rational understanding.

But as the Alaska Supreme Court has previously recognized, “[t]he presence of some degree of mental illness is not an invariable barrier to prosecution.” A defendant may have some degree of impaired functioning but still be “minimally able to aid in his defense and to understand the nature of the proceedings against him.” To a large extent, therefore, “each case must be considered on its particular facts.”

Here, the record indicates that the trial court took the competency concerns raised by the defense counsel very seriously. The court held multiple hearings on Gamble’s competency, including a full evidentiary hearing at which the forensic psychologist testified and was questioned by the prosecutor, the defense attorney, and the judge. Moreover, the court did not simply defer to the psychologist’s opinion. Instead, the court made its own independent findings and continued to make additional findings at later hearings, demonstrating the court’s awareness that Gamble’s situation was not necessarily stable and that the highly intrusive delusions that previously presented a barrier to his competency could quickly return.

On appeal, Gamble argues that the trial court should have deferred to the defense attorney’s assertion that Gamble was unable to assist in his defense because the defense attorney was the only person in a position to make that assessment.

We agree that a defense attorney is in a unique position with regard to assessing a defendant’s ability to assist in his own defense and that a defense attorney’s assessment of the defendant’s functioning is therefore an important factor for the court to consider. But ultimately the question of whether the defendant is competent to stand trial is a determination that the trial court must make independently based on all of the information before it. Thus, just as it would be error for the trial court to defer to the forensic psychologist’s assessment of Gamble’s competency, so too would it be error for the trial court to simply adopt the defense attorney’s perspective of the defendant’s incompetency, without making its own independent determination based on all the information before it.

[…]

Given the record before us, we conclude that the trial court did not err in rejecting this argument and in finding that Gamble was competent to stand trial.

Conclusion

We AFFIRM the judgment of the superior court.

In Alaska, if a defendant is found to be incompetent, the court is obligated to commit the defendant to the care of a mental institution for a period of time to achieve “restoration.” AS 12.47.100(b). Since competency is a question of cognitive ability at the time of the proceeding, a criminal defendant may be restored through treatment and medication. If a defendant is not “restorable,” but still dangerous, the defendant may be committed to a mental institution until the person no longer suffers from the mental disability and is no longer dangerous. The government bears the burden of establishing a person is dangerous. If a case is dismissed as a result of incompetence, it is dismissed “without prejudice,” meaning the government can refile criminal charges if the defendant becomes competent at a later date.

Pieniazek v. State, 394 P.3d 621 (Alaska App. 2017)

In the following case, the court expands on how to determine if a defendant is competent. What does it mean to be able to understand the proceedings against oneself and be able to assist in one’s own defense?

394 P.3d 621

Court of Appeals of Alaska.

Stanly PIENIAZEK, Appellant,

v.

STATE of Alaska, Appellee.

February 24, 2017

OPINION

Judge ALLARD.

Stanly Pieniazek was found competent to stand trial following a competency hearing before Fairbanks Superior Court Judge Michael P. McConahy. A jury later found Pieniazek guilty of two counts of third-degree assault for shooting a gun at two state troopers after they responded to a report of a disturbance at Pieniazek’s property in Fairbanks.

On appeal, Pieniazek argues that the superior court erred in determining that he was competent to stand trial. For the reasons explained here, we agree with Pieniazek that the superior court misapplied the factors listed in AS 12.47.100(e) and failed to conduct an independent and contemporaneous assessment of Pieniazek’s competency. Accordingly, we remand Pieniazek’s case to the superior court for reconsideration and, if feasible, a retrospective determination of his competency to stand trial.

Background facts

Pieniazek, a Polish immigrant with limited English proficiency, is eighty years old. The events that gave rise to this case took place in May 2012, when Pieniazek was seventy-five years old. At the time of the shooting, Pieniazek was living in squalor at his property in Fairbanks in a collection of structures connected by self-constructed “tunnels” that witnesses described as dilapidated and unsanitary. Although Pieniazek was appointed a public guardian two years prior, due to his behavior during a separate criminal case, Pieniazek rebuffed his guardian’s attempts to place him in assisted living, and he twice left the facility in which he was placed. The record before the trial court indicated that Pieniazek was employed from 1969 to approximately 1991, when he retired. The record also indicated that although Pieniazek possessed a driver’s license as late as 2011, he was last observed driving in February 2010.

Prior to trial, Pieniazek’s attorney filed a motion for a judicial determination of competency. Pieniazek was then evaluated twice: first by clinical psychologist Dr. Siegfried Fink, who concluded that Pieniazek had dementia and was incompetent to stand trial; and later by state forensic psychologist Dr. Lois Michaud, who rejected Fink’s diagnosis of dementia and instead concluded that Pieniazek was malingering, based on his refusal to communicate with her.

Fairbanks Superior Court Judge Michael McConahy subsequently held a hearing in May 2013 at which Dr. Fink and Dr. Michaud elaborated on their respective diagnoses. In addition, three other witnesses testified: Ruth Retynski, Pieniazek’s public guardian, as well as Fairbanks Correctional Center (FCC) officers Joanne Murrell and Jerry Watson. Murrell and Watson had both dealt extensively with Pieniazek while he was in custody awaiting trial in this case. In relevant part, Retynski, Murrell, and Watson each described a number of Pieniazek’s strange behaviors.

Retynski testified that she struggled to find an assisted living facility for Pieniazek, partly because she could not determine whether his behavior was due to mental illness or dementia. But Retynski also testified that Pieniazek was manipulative, and that there were times during her conversations with Pieniazek that she felt he was pretending not to understand her when she “didn’t give him exactly what he wanted.”

The FCC corrections officers testified that Pieniazek’s mental condition was extremely poor during his incarceration: Pieniazek hoarded and ate spoiled food, refused to shower unless “tricked” into doing so, struggled to complete all but the most simple tasks, generally did not communicate with staff or other inmates, and was kept in administrative segregation for the sake of both his and others’ safety. Officer Murrell testified that Pieniazek had “moments where he knows what he’s talking about … [and] moments where he’s just babbling.” She also testified that Pieniazek would sometimes “in the middle of the night … pack up all his stuff, fold everything up, organize everything, and just bang on the door and [say] open the door, I’m ready to go home.” Dr. Fink also noted in his report that the FCC staff members he interviewed “observed a significant decline in [Pieniazek’s] level of functioning especially in the last year.”

The trial judge found Pieniazek competent to stand trial, crediting Retynski’s and Dr. Michaud’s testimony that Pieniazek was sometimes “communicative.” The trial judge also noted that AS 12.47.100(e) directs a court determining a defendant’s competency to take into account “whether the person has obtained a driver’s license, is able to maintain employment, or is competent to testify as a witness under the Alaska Rules of Evidence.” The trial judge concluded that these conditions had been met in Pieniazek’s case because Pieniazek was “able to maintain employment since he got [to the United States] until his retirement [in 1991]” and that, although Pieniazek did not have a current driver’s license, he had a “currently registered vehicle on his property” in 2011 and “gets around.”

[…] Pieniazek …testified briefly in the current case. In the brief time he was on the stand, he answered his attorney’s initial questions in Polish and then answered his attorney’s later questions with “I don’t know” and silence.

Alaska law regarding competency determinations

Under Alaska law, a criminal defendant is incompetent to stand trial if, “as a result of a mental disease or defect … the defendant is unable to understand the proceedings against the defendant or assist in the defendant’s own defense.” Alaska Statute 12.47.130(5) defines “mental disease or defect” as “a disorder of thought or mood that substantially impairs judgment, behavior, capacity to recognize reality, or ability to cope with the ordinary demands of life.” The statutory definition further clarifies that “mental disease or defect” also includes “intellectual and developmental disabilities that result in significantly below average general intellectual functioning that impairs a person’s ability to adapt to or cope with the ordinary demands of life.”

A defendant who is incompetent may not be tried, convicted, or sentenced so long as his incompetency exists. The conviction of a defendant who is incompetent violates due process of law.

We have previously emphasized that, “[b]ecause the integrity of the judicial proceeding is at stake when the competency of a criminal defendant is in question, a trial court has a duty to order a competency evaluation whenever there is good cause to believe the defendant may be incompetent to stand trial.” Moreover, “because a defendant’s mental state may deteriorate under the pressures of incarceration or trial, a trial court must be responsive to competency concerns throughout the criminal proceeding.”

The standard for determining lack of competency, although originally formulated in judicial decisions, is now codified in AS 12.47.100. This statute provides that “[a] defendant is presumed to be competent” and that “[t]he party raising the issue of competency bears the burden of proving the defendant is incompetent by a preponderance of the evidence.” When the court raises the issue of competency, the burden of proving the defendant is incompetent “shall be on the party who elects to advocate for a finding of incompetency.”

Alaska Statute 12.47.100(e)-(g) directs the trial court to consider a variety of factors in assessing a defendant’s competency to stand trial. Subsection (e) provides a list of factors that the court is required to consider in determining “whether a person has sufficient intellectual functioning to cope with the ordinary demands of life.” These factors are:

whether the person has obtained a driver’s license, is able to maintain employment, or is competent to testify as a witness under the Alaska Rules of Evidence.

Subsection (f) provides a list of non-exhaustive factors that the court is required to consider in determining “if the defendant is able to understand the proceedings against the defendant.” These factors include:

whether the defendant understands that the defendant has been charged with a criminal offense and that penalties can be imposed; whether the defendant understands what criminal conduct is being alleged; whether the defendant understands the roles of the judge, jury, prosecutor, and defense counsel; whether the defendant understands that the defendant will be expected to tell defense counsel the circumstances, to the best of the defendant’s ability, surrounding the defendant’s activities at the time of the alleged criminal conduct; and whether the defendant can distinguish between a guilty and not guilty plea.

Lastly, subsection (g) provides a list of non-exhaustive factors that the court is required to consider in determining if the defendant is “unable to assist in the defendant’s own defense.” These factors include:

whether the defendant’s mental disease or defect affects the defendant’s ability to recall and relate facts pertaining to the defendant’s actions at times relevant to the charges and whether the defendant can respond coherently to counsel’s questions.

Subsection (g) also provides:

A defendant is able to assist in the defense even though the defendant’s memory may be impaired, the defendant refuses to accept a course of action that counsel or the court believes is in the defendant’s best interest, or the defendant is unable to suggest a particular strategy or to choose among alternative defenses.

Why we remand Pieniazek’s case for reconsideration

As explained above, AS 12.47.100(e)-(g) directs a trial court to consider a variety of factors in determining whether a defendant is competent to stand trial.

[…]

[W]hen the court evaluated the factors listed in AS 12.47.100(e), it did not evaluate these factors in terms of Pieniazek’s current ability to function and cope with the ordinary demands of life. Instead, it evaluated these factors exclusively in terms of Pieniazek’s ability to function in the past—including, at times, the distant past. For example, the trial court noted that “I don’t think anybody is saying that [Pieniazek] currently has an operator license,” but the trial court nevertheless found it significant that “it seems clear that he’s driven in the past, and [ ] had a—in 2011 at least, a currently registered vehicle.” The trial court also found it significant that Pieniazek “maintain[ed] employment since he got here until his retirement” even though Pieniazek’s retirement was in 1991—more than twenty years before the 2013 competency hearing. Lastly, the trial court found it significant that Pieniazek had testified on his own behalf in a prior criminal trial that took place approximately two years earlier. But, as already noted, the prior trial had not included a competency evaluation. Moreover, Pieniazek’s testimony at that prior trial was largely incoherent, and his behavior ultimately resulted in the court appointing him a public guardian.

Taken together, the trial court’s remarks indicate that the court misapplied the factors under AS 12.47.100(e) and failed to adequately investigate whether Pieniazek was competent at the time of trial, rather than at some point in the past. The record also indicates that the court failed to properly document its consideration of the relevant factors under AS 12.47.100(f)-(g).

As the Alaska Supreme Court has previously cautioned, competency is not a static concept, and the trial court’s duty to determine competency is “not one that can be once determined and then ignored.” The need to focus on the defendant’s current level of functioning was particularly acute in this case, given that there had been a diagnosis of progressive dementia from one expert and witness testimony that Pieniazek’s functioning had significantly deteriorated over the last year.

[…]

Conclusion

We REMAND this case to the superior court for reconsideration of the defendant’s competency on the current record[.]

Insanity

Insanity is much different than competency. Insanity refers to whether a person should be criminally responsible for their crime even though they suffer from a severe mental illness. Unlike competency, insanity focuses on the defendant’s culpability at the time of the offense.

Also, unlike competency, there is no constitutional right to an insanity defense. In 2020, the US Supreme Court found that a mentally ill defendant does not have a constitutional right to present an insanity defense at trial. See Kahler v. Kansas, __ U.S. __, 140 S. Ct. 1021 (2020). That said, nearly every jurisdiction authorizes some form of an insanity defense. In fact, as of April of 2021, only four jurisdictions – Kansas, Montana, Utah, and Idaho – do not have an affirmative insanity defense. The insanity defense is the subject of much debate and receives significant attention in the media, in part because it excuses even the most evil and abhorrent conduct, and in many jurisdictions, like Alaska, functions as a perfect defense resulting in an acquittal. But remember, the insanity defense is rarely used, and even more rarely successful. As you will see, it is difficult to prove legal insanity.

The insanity defense is supported by two policies: First, persons who suffer significant and persistent mental disease or defect may not have control over their conduct. This is similar to a defendant who is hypnotized or sleepwalking. Second, severe mental illness may prevent a person from forming the culpable mental state necessary for the crime. Without the ability to control conduct, or the ability to understand that the conduct is morally wrong, there is little moral justification for punishing a legally insane defendant. Treatment, and not punishment, is the appropriate remedy.

Legal insanity differs from medical insanity. While the purpose of a medical diagnosis is to eventually cure the defendant’s mental illness, the purpose of criminal law is to punish criminal behavior. A defendant’s conduct is not excused – even if caused by a mental illness – if the defendant or society can benefit from punishment (through rehabilitation, deterrence, or incapacitation). Most mental diseases or defects do not rise to the level of legal insanity.

In all jurisdictions, the defense of insanity is a creature of statute and, as a result, variations exist. Historically, there are four primary variations of the insanity defense: M’Naghten, irresistible impulse, substantial capacity, and Durham. As you will see, Alaska’s insanity framework is an amalgamation of nearly all of them.

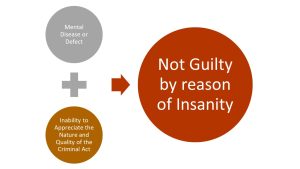

Although insanity operates as a perfect defense and relieves the defendant of criminal responsibility for the crime, a person found not guilty by reason of insanity (NGI) is not immediately released back into the community. Under normal circumstances, if a defendant is NGI, they are civilly committed to a mental institution for treatment. Once the defendant demonstrates that they are not a danger to society due to their mental disease or defect, the defendant is released into the community.

M’Naghten Rule

The M’Naghten Rule is derived from the landmark 1843 British case, M’Naghten, 8 Eng. Rep. 718 (1843). It is often referred to as the right-wrong test. The defendant, Daniel M’Naghten, was under the paranoid delusion that the Prime Minister of England, Sir Robert Peel, was trying to kill him. When he tried to shoot, who he believed to be Sir Peel, he inadvertently shot and killed Sir Peel’s secretary, Edward Drummond. M’Naghten was acquitted of Drummond’s murder by reason of insanity. As a result of the verdict, the House of Lords developed what later became known as the M’Naghten Rule.

The rule contains two prongs. The first prong of the M’Naghten test (sometimes referred to as the “cognitive incapacity” prong) asks whether the defendant knew what they were doing — i.e., whether the defendant understood the nature and quality of their conduct. A defendant does not know the nature and quality of a criminal act if, as the result of a mental disease or defect, the defendant is completely oblivious to what he or she is doing.

The second prong (sometimes referred to as the “moral incapacity” or “wrongfulness” prong) asks whether the defendant could understand that their conduct was wrong — i.e., whether the defendant appreciated the wrongfulness of their actions. A defendant does not appreciate the wrongfulness of their actions when they engage in the criminal act because they are acting under the command of a divine being, caused by their mental disease or defect.

A defendant need only satisfy one of the prongs. As you can see, the M’Naghten rule focuses on the defendant’s cognitive awareness of his actions, rather than his ability to control his conduct. Since its creation, the M’Naghten rule has been the primary test of criminal responsibility in the United States, and the exclusive test in a majority of American jurisdictions, England, and Canada.

Example of Insanity under the M’Naghten rule

Susan, a diagnosed schizophrenic, drowns her two young children in the bathtub. Susan’s husband finds the deceased children when he returns home from an errand. Susan claims that she was directed to drown her children by Zeus, the greatest of all gods. According to Susan, Zeus told her that her children were not children, but blue squares and that to enter heaven, Susan had to eliminate all blue squares on earth. At the murder trial, Susan pleads not guilty by reason of insanity.

In a M’Naghten rule jurisdiction, Susan could successfully claim she was suffering from a mental disease or defect (schizophrenia) and, as a result of her mental illness, she did not know the nature or quality of her conduct (she thought her children were blue squares), nor did she appreciate the wrongfulness of her conduct (Zeus told her to eliminate blue squares). Thus, under the M’Naghten Rule, Susan is likely not guilty by reason of insanity. Susan would likely be committed to a mental institution until she is no longer a danger to society. Susan would not be punished for her conduct.

Irresistible Impulse Test

Another variation of the insanity defense is the irresistible impulse test. The irresistible impulse test focuses on the defendant’s cognitive awareness and the defendant’s will. The crux of the test is violation, or free choice. As a result of the person’s “disease of mind” the defendant did not know right from wrong, and the mental illness destroyed the defendant’s free will and caused the defendant to commit the criminal act. The challenge with the irresistible impulse test is distinguishing between conduct that can be controlled and conduct that cannot. The irresistible impulse test is rejected by most jurisdictions. In some cases, the irresistible impulse test is easier to prove than the M’Naghten rule, resulting in the acquittal of more mentally ill defendants.

Substantial Capacity Test

The substantial capacity test is the insanity test set forth in the Model Penal Code, which considers a defendant legally insane if, as a result of mental disease or defect, they lacked “substantial capacity either to appreciate the wrongfulness of their conduct or to conform [their] conduct to the requirements of the law.” Model Penal Code §4.01(1). The substantial capacity test combines the cognitive element of M’Naghten with the volitional element of the irresistible impulse insanity, thus resulting in an expanding type of mental illness constituting “legal insanity.” See e.g., Lord v. State, 489 P.3d 374, 381 (Alaska App. 2021) (Allard, J. concurring).

It is easier to establish legal insanity under the substantial capacity test because both the cognitive and volitional elements are more flexible. Unlike the M’Naghten rule, the substantial capacity test relaxes the requirement for the complete inability to understand or know the difference between right and wrong. Instead, the defendant must lack substantial, not total, capacity. The “wrongfulness” in the substantial capacity test is “criminality,” which is a legal wrong, not a moral wrong. Further, unlike the irresistible impulse insanity defense, the defendant must lack substantial, not total, ability to conform their conduct to the requirement of the law.

The Durham Rule (Product Test)

The final insanity test we will explore is the Durham rule, which is currently used in only one jurisdiction – New Hampshire, where it has been used since the late 1800s. The Durham rule was also adopted by the Circuit Court of Appeals in Durham v. U.S., 214 F.2d 862, 874-75 (D.D. Cir.1954), and articulated legal insanity as “an accused is not criminally responsible if his unlawful act was the product of mental disease or mental defect.” The Durham rule is sometimes referred to as the product test. Generally speaking, the Durham rule is akin to a proximate causation analysis – that is, did the defendant’s mental disease or defect cause the criminal conduct.

The Court failed to provide definitions of product, mental disease, or mental defect, resulting in it being very difficult to apply. The test, originally designed to be hyper-flexible and intended to widen the range of relevant expert testimony available to the jury, resulted in inconsistent jury verdicts. See e.g., Washington v. U.S., 390 F.2d 444 (D.D.Cir. 1967). The test was used in the District of Columbia for nearly twenty years before being superseded by federal statute. See e.g., 18 U.S.C. 17 (2022). The federal government has abandoned the Durham rule in favor of a M’Nagthen-style statutory test.

Alaska’s History of Culpability Verdicts

Alaska has a unique approach to legal insanity. From statehood until 1972, Alaska largely followed the M’Naghten rule of legal insanity. In 1982, the Alaska legislature revised Alaska’s insanity laws in response to several high-profile cases, including the Charles Meach murder trial. Charles Meach killed four teenagers in Russian Jack Park after being released from the Alaska Psychiatric Institute (API) following an earlier murder acquittal by reason of insanity. The Alaska legislature eliminated the moral incapacity/wrongfulness prong of the M’Naghten test, resulting in a highly restrictive definition of insanity – the single cognitive incapacity prong (“the nature and quality” prong). Alaska also created a GBMI verdict that included the moral culpability prong and the substantial capacity prong. No other jurisdiction has taken this approach to its insanity defense.

The More You Know…

In 1982, Charles Meach was charged with killing four teenagers in Russian Jack Park. Meach pled “not guilty because of mental disease or defect,” and shortly thereafter the Alaska legislature substantially revised Alaska’s insanity laws. The case received significant notoriety because Meach successfully used the same plea in 1973 after he was acquitted by reason of insanity of brutally murdering a woman he met at a topless bar. The New York Times covered the story and the resulting change in the law. See Wallace Turner, New Law on Insanity Plea Stirs Dispute in Alaska, N.Y. Times, June 22, 1982 at D:27. The article can be accessed through the Consortium Library at the University of Alaska Anchorage, using your student credentials. For additional information, Alaska Court of Appeals Chief Judge Allard outlined the history of Alaska’s insanity laws in her concurring opinion of Lord v. State, 489 P.3d 374, 381 (Alaska App. 2021) (Allard, J. concurring).

In Alaska, insanity is an affirmative defense. The defendant has the burden to prove that they were legally insane at the time the crime was committed. Insanity is a perfect defense, and the defendant who successfully proves insanity must be acquitted of criminal wrongdoing.

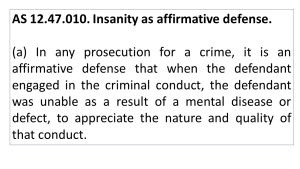

Figures 8.1 & 8.2 – AS 12.47.010 Insanity Statute and Diagram

Guilty But Mentally Ill

Alaska’s guilty but mentally ill (GBMI) verdict is a novel verdict and one specially created by the legislature. See State v. Clifton, 315 P.3d 694 (Alaska App. 2013). When the trier of fact enters a verdict of GBMI, the trier of fact is finding that “because of mental disease or defect, the defendant lacked the substantial capacity either to appreciate the wrongfulness of their conduct or to conform their conduct to the requirements of the law.” See id. Approximately thirteen states have adopted similar GBMI laws.

Although legal insanity is an affirmative defense that the defendant must prove by a preponderance of the evidence, GBMI is an alternative verdict that can be raised by either the government or the defendant. See State v. Lewis, 195 P.3d 622, 639 (Alaska App. 2008).

Alaska’s GBMI verdict is uniquely punitive. Unlike a defendant found guilty (but not mentally ill), a GBMI defendant is ineligible for mandatory and discretionary parole while they are receiving mental health treatment for their mental illness. Thus, a GBMI defendant is required to serve the full portion of their sentence in custody while they suffer from a mental illness that causes the defendant to be dangerous to the public. AS 12.47.050(b). This rule causes a perverse result: defendants have an incentive to deny the existence of their mental illness during trial to avoid the harsh consequences of GBMI.

Figures 8.3 & 8.4 – AS 12.47.030. Alaska GMBI Statute and Diagram

![AS 12.47.030. Guilty but mentally ill. (a) A defendant is guilty but mentally ill if, when the defendant engaged in the criminal conduct, the defendant lack, as a result of a mental disease or defect, the substantial capacity either to appreciate the wrongfulness of that conduct or to conform that conduct to the requirements of the law. A defendant found guilty but mentally ill is not relieved of criminal responsibility for criminal conduct and is subject to [mental health treatment and criminal sentencing]](https://pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/2614/2022/09/12.47.030-Diagram-300x169.jpg)

Lord v. State, 262 P.3d 855 (Alaska App. 2011)

Cynthia Lord, the defendant in the following case, murdered her three sons while unquestionably suffering a severe, persistent mental illness. As you read the opinion, pay close attention to how the Court distinguishes between a legally insane defendant and a guilty but mentally ill defendant.

262 P.3d 855

Court of Appeals of Alaska.

Cynthia LORD, Appellant,

v.

STATE of Alaska, Appellee.

Nov. 4, 2011.

OPINION

COATS, Chief Judge.

Cynthia Lord was charged with three counts of murder in the first degree for killing her three sons, Christopher, Michael, and Joseph. Superior Court Judge Philip R. Volland conducted a non-jury trial. Lord asserted that she was not guilty by reason of insanity. Judge Volland instead found that Lord was guilty but mentally ill.

Lord asserts that Judge Volland erred in reaching this verdict. She contends that she established that she was not guilty by reason of insanity by showing that she did not “appreciate the nature and quality” of her conduct. She also attacks Judge Volland’s interpretation of the Alaska statutes defining the defense of insanity, and argues that those statutes are unconstitutional.

In this decision we uphold Judge Volland’s verdict that Lord was guilty but mentally ill. We also uphold the constitutionality of the Alaska statutes that define the defense of insanity.

Alaska’s insanity defense

Before 1972, Alaska applied a version of the M’Naghten test. Under this test, a defendant could be found not guilty by reason of insanity if she either did not appreciate the nature and quality of her conduct or if she did not understand the wrongfulness of her conduct. In 1972, the Alaska Legislature added the “substantial capacity test,” which allowed the defense of insanity when the defendant lacked the substantial capacity to conform her conduct to the requirements of the law.

In 1982, the legislature amended AS 12.47, greatly limiting the defense of insanity. There are now two ways for a defendant to gain an acquittal as a result of insanity. Under AS 12.47.010(a), the defendant can establish insanity as an affirmative defense if the defendant “was unable, as a result of mental disease or defect, to appreciate the nature and quality of [her] conduct.” […]

The greatest change in the statutes governing the insanity defense was the creation of the verdict of “guilty but mentally ill.” Under AS 12.47.030, a defendant who engages in criminal conduct is guilty but mentally ill if, because of a mental disease or defect, the defendant lacked “the substantial capacity either to appreciate the wrongfulness of that conduct or to conform that conduct to the requirements of the law.” Under the law as it existed prior to the 1982 amendments, a defendant would be found not guilty by reason of insanity under this standard.

A defendant found guilty but mentally ill is not relieved of criminal responsibility. […] The statute directs the Department of Corrections to provide mental health treatment to the defendant until the defendant “no longer suffers from a mental disease or defect that causes the defendant to be dangerous to the public peace or safety.” During treatment, the defendant may not be released on furlough or on parole. At the successful conclusion of treatment, the defendant must serve the remainder of her sentence.

This disposition for persons found guilty but mentally ill differs from the disposition for persons found not guilty by reason of insanity. Defendants found not guilty by reason of insanity may be released immediately if they prove to the court by clear and convincing evidence that they are “not presently suffering from any mental illness that causes [them] to be dangerous to the public.” Until that time, they are committed to the Commissioner of Health and Social Services for treatment for a period not to exceed the maximum term of imprisonment for the crime for which they were found not guilty by reason of insanity. They are entitled to yearly hearings where they have the opportunity to establish that they are “not presently suffering from any mental illness that causes [them] to be dangerous to the public.” If they are still in custody at the end of the maximum term of imprisonment for the crime for which they were found not guilty by reason of insanity, the State can file a petition for civil commitment.

Factual and procedural background

Judge Volland issued a written verdict in this case. The following facts are from that verdict:

Cynthia Lord is gravely disabled by mental illness. She suffers from schizoaffective disorder, depressive type. This disorder is characterized by delusions, hallucinations, disordered thought process and disturbed emotional experience. Ms. Lord has been in and out of psychiatric hospitals since age 17, and had been receiving mental health services in Anchorage regularly since 1994. Her condition is not likely to improve although medication may reduce her hallucinations. Since at least 2003, Ms. Lord has had delusions about a force she calls “Evil,” delusions about being watched by police and the CIA, and about Satanic labels on food. Although suffering from delusions part of the time, Ms. Lord has been able to secure employment in the past, attend school at Wayland Baptist University, take care of her children, and undertake daily life care responsibilities such as shopping, cooking, housecleaning, etc.

On March 16, 2004, the Anchorage Police Department received a 911 call from Ms. Lord reporting that she had “killed my three boys.” APD had had experiences with Ms. Lord before, and the police response was initially skeptical about her report. However, when officers entered her home, they found the bodies of Ms. Lord’s three children: Joseph, age 16, Michael, age 18, and Christopher, age 19. Each boy had been killed by a single shot to the head.

Ms. Lord gave a voluntary statement to police that day. She told APD Detectives Mark Huelskoetter and Glen Klinkhart that she had purchased a gun in October 2003, when she made the decision to kill her sons. Ms. Lord said that on the day before [she killed her sons] she mixed some of her medication with Crystal Light so that her boys would drink it and get sleepy. She set her alarm for early in the morning and woke at approximately 2:30 a.m. It took her about an hour to work up the courage to kill Michael, her eighteen year old, during which time she drank alcohol. She first worried that the gunshot would wake the other boys or her neighbors. She then covered Michael’s body with a blanket and waited for her other sons to wake up.

Ms. Lord told police that when Joseph, the youngest, woke up she told him that Michael was sick and would not be going to school. Joseph then left to attend classes at East High. When Christopher woke up around 10:00 a.m., she waited until he was playing video games in front of the entertainment center. She then shot him in the head, pulled his body into another room, and covered it with clothes so that Joseph would not see it when he came home. Christopher had asked about Michael, but Ms. Lord told him that Michael was sick as she had told Joseph. She then locked the door so “that when Joey came home … I would be ready with the gun.” When Joseph returned from school at around 2:30 p.m. and walked in the door, Ms. Lord waited until Joseph’s face was turned away from her and shot him in the back of the head. She then contemplated killing herself for a couple of hours and eventually called the police around 4:30 p.m. Ms. Lord told detectives she expected punishment for what she did.

Several psychologists testified at the trial. Judge Volland summarized their testimony:

Dr. [David] Sperbeck spent approximately eleven hours interviewing Ms. Lord, exclusive of psychological testing.

Dr. Sperbeck testified that Ms. Lord had good recall of events and described the shootings to him in greater detail than to police. He testified that Ms. Lord told him that she couldn’t tell what was real or not and that she didn’t want her children to grow up in a world of deception and lies. Ms. Lord told Dr. Sperbeck that she knew the boys were her children but that they acted like robots. Dr. Sperbeck testified that, despite the fact that Ms. Lord’s actions were prompted by her hallucinations, she clearly knew that she was killing her children.

He testified that his opinion was that “Lord understood the nature and quality of her conduct” in that she “under[stood] the consequences of [her] act[s].” She “understood that placing a gun to the head of her children would kill them.” Dr. Sperbeck was confident from Lord’s repeated statements to him that she knew she was killing her boys. Judge Volland found that Dr. Lawrence Maile testified similarly to Dr. Sperbeck:

Based on Ms. Lord’s systematic planning to kill her sons, her ability to identify her sons, distinguish them as human beings, and describe the consequences of her direct actions on her sons, Dr. Maile expressed the professional opinion that there [were] no impediments to Ms. Lord being found criminally responsible for the charges she faces.

Dr. Bruce Gage testified for the defense. Judge Volland summarized his testimony as follows:

Dr. Gage concluded that Ms. Lord did “understand that she was killing her boys so, to that extent, she understood the nature of her act.” However, Dr. Gage was of the opinion that this did not take into account Ms. Lord’s reason for killing her children, i.e., to save them. Dr. Gage was of the opinion that if this motivation and context for her act is considered, Ms. Lord did not understand the nature and quality of her conduct. Dr. Gage opined that if Ms. Lord believed she was saving her children, she did not appreciate the quality of her act because she did not appreciate its true consequences.

Cynthia Lord testified at the trial. Judge Volland summarized her testimony as follows:

During her testimony, [Ms. Lord] spoke with the same flat affect that was characteristic of her interview with police, and apparently characteristic of her discussions with mental health professionals for the last decade. She described her delusions at length. Ms. Lord retold the killing of her children with the same detail she gave to police. On cross-examination, Ms. Lord admitted that she knew she was pointing a gun at Michael and that when she shot the gun it would kill him. She stated that had her daughter been in the home at the time, she would have killed her also “because she’s one of the siblings.” Ms. Lord testified that she knew Michael was dead after she shot him. She also admitted that after killing Joseph, she thought: “Oh my god, I killed my son.” Regarding Christopher, she admitted on cross-examination that “I got the gun and I shot him in the head” and that she had told [another examining doctor] that she shot him in the back of the head because she did not want the last thing he saw to be his mother shooting him. As to Joseph, she said “I shot him.” She acknowledged that when she shot her boys, she intended to pull the trigger and knew that a bullet would go into their heads and they would die. She admitted they were her boys and that they were human. She said she thought about killing herself “because she couldn’t live without them.”

In reaching his verdict, Judge Volland first addressed whether Lord had the mens rea for murder in the first degree. [Under the diminished capacity doctrine,] a defendant is not guilty by reason of insanity if, “as a result of mental disease or defect, there is a reasonable doubt as to the existence of a culpable mental state that is an element of the crime.”

To establish the mens rea for murder in the first degree, the State had to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that Lord intended to cause the death of Michael, Joseph, and Christopher. Alaska law states that a person acts intentionally “when the person’s conscious objective is to cause that result; when intentionally causing a particular result is an element of an offense, that intent need not be the person’s only objective.”

Judge Volland found that “the evidence is overwhelming that Ms. Lord engaged in a deliberate, conscious, and detailed plan to kill her three sons.” He then set out Lord’s meticulous planning that preceded the murders, and noted the opinions of the psychologists who testified at trial that Lord intended to kill her sons:

According to Dr. Sperbeck and Dr. Maile, Ms. Lord knew her sons were her sons at the time of the shootings. Even Dr. Gage stated in his written report that Lord knew she was killing her sons. Dr. Gage also acknowledged that Ms. Lord had to have the intent to kill her sons to also have the intent to save them.

After finding that Lord had the mens rea to commit murder in the first degree, Judge Volland examined whether Lord had established the affirmative defense of insanity. Under AS 12.47.010(a), a defendant is not guilty by reason of insanity if the defendant establishes by a preponderance of the evidence that, when engaged in the criminal conduct, the defendant was “unable, as a result of mental disease or defect, to appreciate the nature and quality of that conduct.”

Judge Volland first discussed … the meaning of AS 12.47.010(a)—in particular, the meaning of “unable, as a result of mental disease or defect, to appreciate the nature and quality of that conduct.” The court observed that the legislative history of the statute contained two examples of defendants who could establish that they were unable to appreciate the nature and quality of their acts under this standard: a defendant who is “unable to realize that he is shooting someone with a gun when he pulls the trigger on what he believes to be a water pistol, or a murder defendant who believes he is attacking the ghost of [his] mother rather than a living human being.” According to the House Judiciary Committee report on the legislation, the defense of insanity would not apply “to a defendant who contends that he was instructed to kill by a hallucination, since the defendant would still realize the nature and quality of his act, even though he thought it might be justified by a supernatural being.”

Turning to the facts of this case, Judge Volland concluded:

[T]o appreciate the nature and quality of murder means that the defendant must have understood the act that he or she engages in will cause the death of another person. Thus, for Ms. Lord to prevail on the defense of insanity under AS 12.47.010(a), she must show, by a preponderance of the evidence, that she was unable, as a result of her mental illness, to recognize that pointing a gun at the head of her sons and pulling the trigger, knowing they were her sons, would kill them.

The court rejects Dr. Gage’s reasoning that understanding the “quality” of an act requires inquiry into the context of the act and the defendant’s motivation. In the court’s view this invites an inquiry into wrongfulness. This is especially true in Ms. Lord’s case. Ms. Lord’s motivation to save her children is precisely why she did not consider the act to be wrongful. Even Dr. Gage admitted that in Ms. Lord’s case, her motivation and belief that her act was not wrong “correspond.”

Judge Volland summarized why he concluded that Lord did not establish that she failed to appreciate the nature and quality of her conduct:

There is much evidence that Ms. Lord appreciated that she was killing her children. She stated the same to Dr. Sperbeck and Dr. Maile and admitted in her own testimony that after killing Michael, she recognized that she had just shot one of her children. Ms. Lord had to work up the courage to shoot Michael. She covered her children after she shot them so she would not see them. She shot her sons in the back of the head or while they were sleeping so they would not see their mother shoot them. She shot each boy in a way that would cause instant death and the least pain. [The court finds that these actions are not consistent with a mother shooting [children] she believes are non-human clones or robots. The evidence at trial that Ms. Lord did not believe her boys were her boys was equivocal at best. The court does not find that Ms. Lord’s statement to Dr. Sperbeck that “I was 80% sure I’d never see them again on this earth” evidenced that she did not believe she was killing them. Ms. Lord’s admissions on cross-examination convinced the court that she knew she was killing her boys.] Because of this, the court concludes that the defense has not established by a preponderance of the evidence that Ms. Lord failed to appreciate the nature and quality of her conduct as a result of her mental disease.

Judge Volland concluded, by a preponderance of the evidence, that Lord was guilty but mentally ill. He concluded that the “evidence is undisputed that Ms. Lord suffers from a severe, disabling mental illness,” and that she “killed her children to save them from ‘Evil’ and to send them to heaven. She believed that she was doing the right thing and would do it over again; she testified to this belief at trial. The court finds her belief genuine and firmly held.”

Why we uphold Judge Volland’s verdict that Lord was guilty but mentally ill

Lord argues that Judge Volland interpreted the Alaska statutes setting out the defense of insanity too narrowly. She argues that, in arriving at his verdict, Judge Volland only applied … the diminished capacity statute, which provides that a defendant is not guilty by reason of insanity if, “as a result of mental disease or defect, there is a reasonable doubt as to the existence of a culpable mental state that is an element of the crime.” Lord argues that the defense of insanity is broader, because AS 12.47.010(a) also establishes an affirmative defense of not guilty by reason of insanity if the defendant engaged in criminal conduct but “was unable, as a result of mental disease or defect, to appreciate the nature and quality of that conduct.”

In rejecting Lord’s insanity defense, Judge Volland found that, even though the “evidence [was] undisputed that Ms. Lord suffers from a severe, disabling mental illness,” Lord formed the culpable mental state to commit murder in the first degree. He found that “the evidence is overwhelming that Ms. Lord engaged in a deliberate, conscious, and detailed plan to kill her three sons.”

Lord agrees that this finding was sufficient for Judge Volland to reject a “diminished capacity” defense[.] But she asserts that Judge Volland erred by using these same findings to reject her affirmative defense of not guilty by reason of insanity under AS 12.47.010. Lord argues that if the legislature intended to restrict the insanity defense to only an inquiry about whether a defendant could form the mens rea to commit the crime, then AS 12.47.010 would be superfluous. She argues that the legislative history of the statutes governing the insanity defense show no intent to limit the defense in this way.

Lord argues that, applying the proper test in AS 12.47.010(a), the evidence at trial established the affirmative defense of insanity because it showed that she had no understanding of the meaning of death, and therefore did not appreciate the nature and quality of her acts. But Judge Volland rejected the factual basis for this argument. He found that Lord knew she was killing her boys and appreciated the nature of death based on her testimony that she “was 80% sure I would never see them again on this earth.”

In explaining his verdict, Judge Volland carefully considered the testimony of the psychologists as well as the evidence of Lord’s hallucinations and delusions. He concluded that, in spite of these mental defects, Lord understood the nature and quality of her acts. He set out her meticulous reasoning and the steps she took as she planned and carried out the killing of her sons. He concluded that she understood what she was doing and understood the concept of death—she knew with substantial certainty that, by killing her sons, she was removing them from this earth and that she would never see them alive again. We conclude that there is no merit to Lord’s claim that Judge Volland failed to make the findings necessary to reject her affirmative defense of insanity.

To find that Lord was guilty but mentally ill, Judge Volland had to find that she lacked “the substantial capacity either to appreciate the wrongfulness of [her] conduct or to conform that conduct to the requirements of the law.” Judge Volland concluded that, because of her mental illness, Lord sincerely believed she was doing the right thing by killing her sons “to save them from ‘Evil’ and send them to heaven.” He found that, because of her mental disease or defect, she lacked the substantial capacity to appreciate the wrongfulness of her conduct. Judge Volland’s findings are supported by the record, and they support his verdict that Lord was guilty but mentally ill.

[…]

Conclusion

The judgment of the superior court is AFFIRMED.

Diminished Capacity

Diminished capacity differs from legal insanity. Whereas insanity absolves a defendant from criminal responsibility for the charged crime, the diminished capacity doctrine only acts to negate specific intent crimes. Diminished capacity allows a defendant to argue that his mental disease or defense precluded him from forming the requisite culpable mental state. AS 12.47.020(a). “The diminished capacity doctrine is based on the theory that while an accused may not have been suffering from a mental disease or defect at the time of his offense, sufficient to absolve him totally of criminal responsibility, the accused’s mental capacity may have diminished by intoxication, trauma, or mental disease to such extent that he did not possess the specific mental state or intent essential to the particular offense.” See Johnson v. State, 511 P.2dd 118, 124 (Alaska 1973). Diminished capacity is a rarely used defense.

Figure 8.5 – Effects of Mental Illness Claims (circular diagram)

Exercise

Answer the following question. Check your answers using the answer key at the end of the chapter.

- Jeffrey is diagnosed with schizophrenia. For fifteen years, Jeffrey kidnaps, tortures, kills, and eats human victims. Jeffrey avoids detection by hiding his victims’ corpses in various locations throughout the city. If the jurisdiction in which Jeffrey commits these crimes recognizes the M’Naghten insanity defense, can Jeffrey successfully plead and prove insanity? Why or why not? Would your answer change under Alaska’s insanity law?