Conspiracy

The last inchoate offense to explore is conspiracy. Frequently referred to as one of the most powerful tools in the prosecutor’s arsenal, conspiracy criminalizes an agreement to commit a crime. A person is guilty of conspiracy if the person intentionally agrees to participate in a “serious felony offense” with one or more individuals. AS 11.31.120. Similar to other inchoate crimes, conspiracy does not require the target crime to be successful. The defendants may never commit the planned offense, and a co-conspirator need not personally know the other co-conspirators. AS 11.31.120(b). Conspiracy is also the only inchoate offense that does not merge with the target crime. Conspiracy is a separate criminal offense. If the defendants commit the crime that is the object of the conspiracy, they are responsible for both the conspiracy and the completed crime.

A conspiracy is complete as soon as the defendants become complicit and commit an overt act with the conspiracy intent. Conspiracy punishes defendants for planning criminal activity – including activity that would be merely preparatory under attempt or solicitation.

Take note that the law of conspiracy intentionally targets groups. This behavior is criminalized due to the dangerousness that surrounds anti-social group activity. See e.g., Wayne R. LaFave, Substantive Criminal Law, §12 (3rd ed. 2018). When individuals collectively engage in unlawful activity, it is more likely that they will be successful. Such activity is also more difficult to stop once set in motion.

Conspiracy – Voluntary Act (Actus Reus)

Conspiracy requires the conspirators to engage in a minimum of two actions: an agreement and an overt act. First, conspirators must agree to commit the target criminal offense. The agreement need not be formal or in writing; in fact, most conspiracies involve informal agreements – that is, individuals engage in tacit, non-spoken alliances to engage in criminal activity, which may be sufficient to establish complicity. Although the agreement need not be formal, it must occur. Merely being present when an agreement is discussed, knowing about the agreement, or even hoping that the target crime will be accomplished cannot establish an agreement. See Use Note, Alaska Criminal Pattern Jury Instruction, 11.31.120(a).

Second, one of the co-conspirators must commit an overt act in furtherance of the conspiracy. The overt act operates as proof that the conspiracy is alive and functioning, as opposed to simple criminal conversations about crime. Take note that only one of the co-conspirators need to commit the overt act; the other co-conspirators need not even be aware the overt act occurred. AS 11.31.120. Make no mistake: a defendant can be held criminally liable for conspiracy if another person commits an overt act in furtherance of the conspiracy unbeknownst to the defendant.

Equally importantly is the overt act need not be criminal – planning or preparatory activity are sufficient. The overt act must be an “act of such character that it manifests a purpose on the part of the actor that the object of the conspiracy be completed.” AS 11.31.120(h)(1). Lawful activities, such as purchasing a getaway car, mailing a letter, or attending a meeting may be sufficient to establish an overt act.

One significant limitation with conspiracy is what may be conspired to – that is, what is the conspiratorial objective (i.e., the target offense). Whereas a person may attempt or solicit any crime, conspiracy is limited to a subset of the most serious felonies. A person may only conspire to commit serious felony offenses. AS 11.31.120(a). “Serious felony offense” includes:

- Murder

- Kidnapping

- First-degree assault (e.g., assault with a deadly weapon)

- First-degree robbery (e.g., armed robbery)

- Sexual assault (e.g., rape)

- Sexual abuse of a minor (e.g., child sexual abuse)

- Drug-trafficking

- First-degree criminal mischief (e.g., blowing up the pipeline)

- First-degree terroristic threatening (e.g., biological attack/terrorism)

- First-degree human trafficking (e.g., slavery)

- First-degree sex trafficking; and

- First- and second-degree arson.

Conspiracy – Culpable Mental State (mens rea)

An agreement to conspire does not happen by accident. Conspiracy is a specific intent crime, and requires a conspirator to act with an “intent to promote or facilitate” the target offense. AS 11.31.120(a). This mental state consists of two components. First, the government must prove that the conspirator intended to agree with their co-conspirator, and (2) intended to commit the target offense.

But remember, conspiracy, by definition, requires more than one active participant; one cannot conspire with oneself. That is not to say both conspirators must have an intent to achieve the conspiratorial objective – the modern trend is that a conspiracy may be formed as long as one of the parties has the requisite intent. Pursuant to this unilateral view of conspiracy, a conspiracy may exist between a defendant and a law enforcement decoy who is pretending to agree. AS 11.31.120(d). Put another way, when analyzing the culpable mental state elements of conspiracy, the focus is on the individual defendant in relation to the larger group. Defenses that may apply to one conspirator are not necessarily available to all of the conspirators.

Example of Conspiracy

Shelley and Sam meet while drinking at their local bar. Both are down on their luck and begin fantasizing about what they would do if they had money. Shelley mentions that she works at a local gas station, which tends to have several hundreds of dollars in cash at closing time. Shelley also tells Sam that the surveillance camera system is broken and her co-worker, Valerie, normally closes the gas station alone. Valerie is extremely meek and fearful and will readily hand over the cash if robbed. Sam asks Shelley if she would like to help him rob the store when Valerie is working. Shelley agrees. The two plan the robbery – Shelley agrees to borrow her roommate’s car and agrees to drive the getaway car during the robbery. Sam agrees to find a handgun to use. Sam and Shelley leave the bar with a plan to meet the following day to commit the robbery. Unbeknownst to Shelley, after the meeting, Sam met an old friend in an alley and bought a gun for the robbery. Shelley and Sam have probably committed conspiracy to commit first-degree robbery. Shelley and Sam have both demonstrated an intent to agree to work together and both have demonstrated an intent to successfully commit the robbery. Finally, Sam has committed an overt act in furtherance of the conspiracy (e.g., purchasing a gun).

Structures of Conspiracies

A conspirator need not know his co-conspirators’ identities. AS 11.31.120(b). As long the conspirator has consciously entered into the conspiracy, “the offender is guilty of conspiring with that other person or persons to commit [the target] crime whether or not the offender knows their identities.” Id. This caveat is important given the structure of many sophisticated, large-scale conspiracies. Sophisticated conspiracies may organize to intentionally defuse individual knowledge about the criminal participants and activity. For example, a criminal organization illegally distributing narcotics in the state may intentionally refuse to share participant identities within the organization. Such security protocols are designed to thwart law enforcement. Although such actions may be effective in limiting criminal investigations, they will not act as a defense to a prosecution of conspiracy.

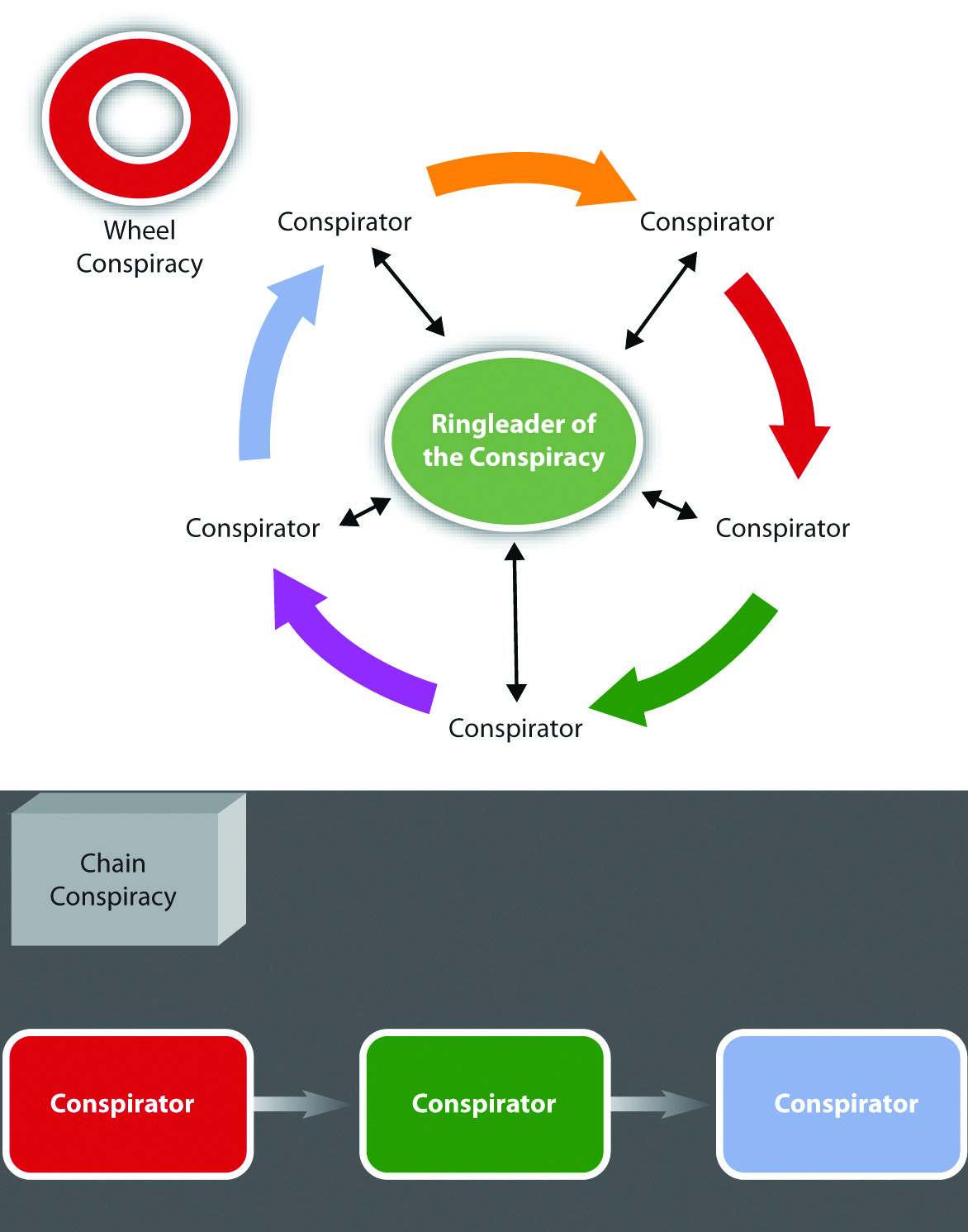

There are two basic large-scale conspiracy organizational formats: wheel and chain conspiracies. A chain conspiracy refers to a group of people who each have a role in carrying out specific actions that lead to a successful criminal outcome. Chain conspiracies operate linearly, like links in a chain but without a central ringleader. An example of a chain conspiracy is a conspiracy to manufacture and distribute heroin, with the manufacturer linked to the transporter, who is linked to the large-quantity dealer, who thereafter sells to a smaller-quantity dealer, who sells to a customer. None of the conspirators may know the identity of the person above (or below) their contact.

A wheel conspiracy has a key person at its center (a ringleader), known as the “hub” who has contact with other members of the conspiracy, known as the “spokes.” The ringleader is interconnected to every other coconspirator. An example of a wheel conspiracy would be a mob boss linked to individual members of the mob following specific commands, all for the benefit of the larger criminal organization.

Whether the conspiracy is wheel, chain, or more informal, individual conspirators need not personally know other members of the conspiracy, and as a result, may be criminally responsible for the conspiracy and the target crimes. Similar to accomplice liability, the failure to prosecute one party to the conspiracy does not relieve a coconspirator from criminal responsibility.

Figure 6.3 Comparison of Wheel and Chain Conspiracies

Merger Doctrine

Unlike the law of attempt and solicitation, conspiracy does not merge with the substantive offense if completed. This is a significant departure from other inchoate offenses. An offender may be prosecuted, convicted, and sentenced for both conspiracy and the completed target crime. See Lythgoe v. State, 626 P.2d 1082 (Alaska 1980)

Defense to Conspiracy – Renunciation

Conspiracy has a long reach – the conspirator need not know their co-conspirators, and if successful in their criminal objective, an offender will be punished for both the conspiracy and the completed crime. But the law of conspiracy is not without its limits. As with other inchoate offenses, a defendant can avoid criminal liability if they freely and completely renounce their criminal intent. AS 11.31.120(f). Similar to other inchoate crimes, renunciation means giving up, refusing, or abandoning the criminal objective.

Renunciation is an affirmative defense to a conspiracy if the defendant manifests “a voluntary and complete renunciation of the defendant’s criminal intent” and prevents the target crime from occurring. AS 11.31.120(f). The defendant needs to take affirmative steps to prevent the target crime. The code requires the defendant to either (1) give a timely warning to law enforcement, or (2) make proper efforts “that prevented the commission of the crime.” In other words, it is not enough that the conspirator attempted to prevent the conspiracy; to relieve oneself of criminal liability, the conspirator must successfully prevent the target crime.

Also, other co-conspirators do not receive the benefit of one’s renunciation. A complete renunciation of one conspirator does not relieve other conspirators of criminal liability.

Example of Renunciation

Remember Shelley and Sam? Let’s assume that after Shelley and Sam agree to rob Valerie at the gas station, Shelley has a change of heart. Before she returns to the bar to meet Sam, she contacts law enforcement and tells them about their plan. Detectives ask Shelley to help them apprehend Sam, and she agrees. Shelley drives to the bar to pick up Sam, and then drives them both to the gas station. Unbeknownst to Sam, the detectives have replaced Valerie with an undercover officer. As soon as Sam pulls out his gun he is arrested. The robbery is unsuccessful. Shelley has likely renounced her participation in the conspiracy – she is likely not guilty of conspiracy (or the completed robbery). Sam, on the other hand, is likely guilty of both conspiracy to commit first-degree robbery and first-degree robbery. Shelley’s voluntary and complete renunciation does not relieve Sam of his criminal liability.

Grading

Similar to both attempt and solicitation, conspiracy is typically graded lower than the target offense. AS 11.31.120(i). If the target offense is classified as an unclassified offense, then conspiracy is a class A offense. If the target offense is a class A felony, then conspiracy is a class B felony offense. Class B and C felony offenses are reduced respectively. The one exception is conspiracy to commit first-degree murder. A person convicted of conspiring to commit first-degree murder remains convicted of an unclassified felony offense.

Conspiracy versus Accomplice Liability

It is important to distinguish the law of conspiracy from the law of legal accountability (accomplice liability). While there can be significant overlap, they are separate and distinct legal concepts. First, the actus reus is different. Under legal accountability, an accomplice is criminally liable to the same extent as the principal so long as the accomplice “aids, abets, or assists” the principal. AS 11.16.110. With conspiracy, the conspirators must agree to the conspiracy and one of the co-conspirators must take an overt act in furtherance of the conspiracy. (Accomplices need not agree to the conspiracy; instead, they simply must aid, abet, or assist the target crime.) Second, the resulting harm is different. Although accomplice liability is broad, the principal must be successful in the target crime. Conspiracy, on the other hand, is an inchoate offense. The object of the conspiracy need not occur. Finally, conspiracy is limited in scope. Conspiracy only applies to serious felony offenses. Accomplice liability is applicable to all criminal offenses.