The Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses

Although Article I of the Constitution prohibits certain legislative branch powers, the Bill of Rights contains most of the constitutional protections afforded to criminal defendants. The Bill of Rights is the first ten amendments to the Constitution. In addition, the Fourteenth Amendment, which was added to the Constitution after the Civil War, added additional protections of due process and equal protection.

For much of U.S. history, the constitutional protections found within the Bill of Rights only applied to the federal government. However, beginning in the 1920s, the US Supreme Court adopted the doctrine of selective incorporation, in which it held most of the constitutional protections found within the Bills of Rights are implicit to due process’s concept of ordered liberty and must be incorporated into the Fourteenth Amendment’s protections and applied to the states. See. e.g., Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961) and Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963). To be clear, not all of the rights guaranteed by the Bill of Rights have been incorporated and applied to the states. But generally speaking, the overwhelming majority of the constitutional protections in the Bill of Rights apply to the States. Thus although the original focus of the Bill of Rights may have only limited the federal government, modern constitutional jurisprudence extends the Bill of Rights protections to all levels of state and local government.

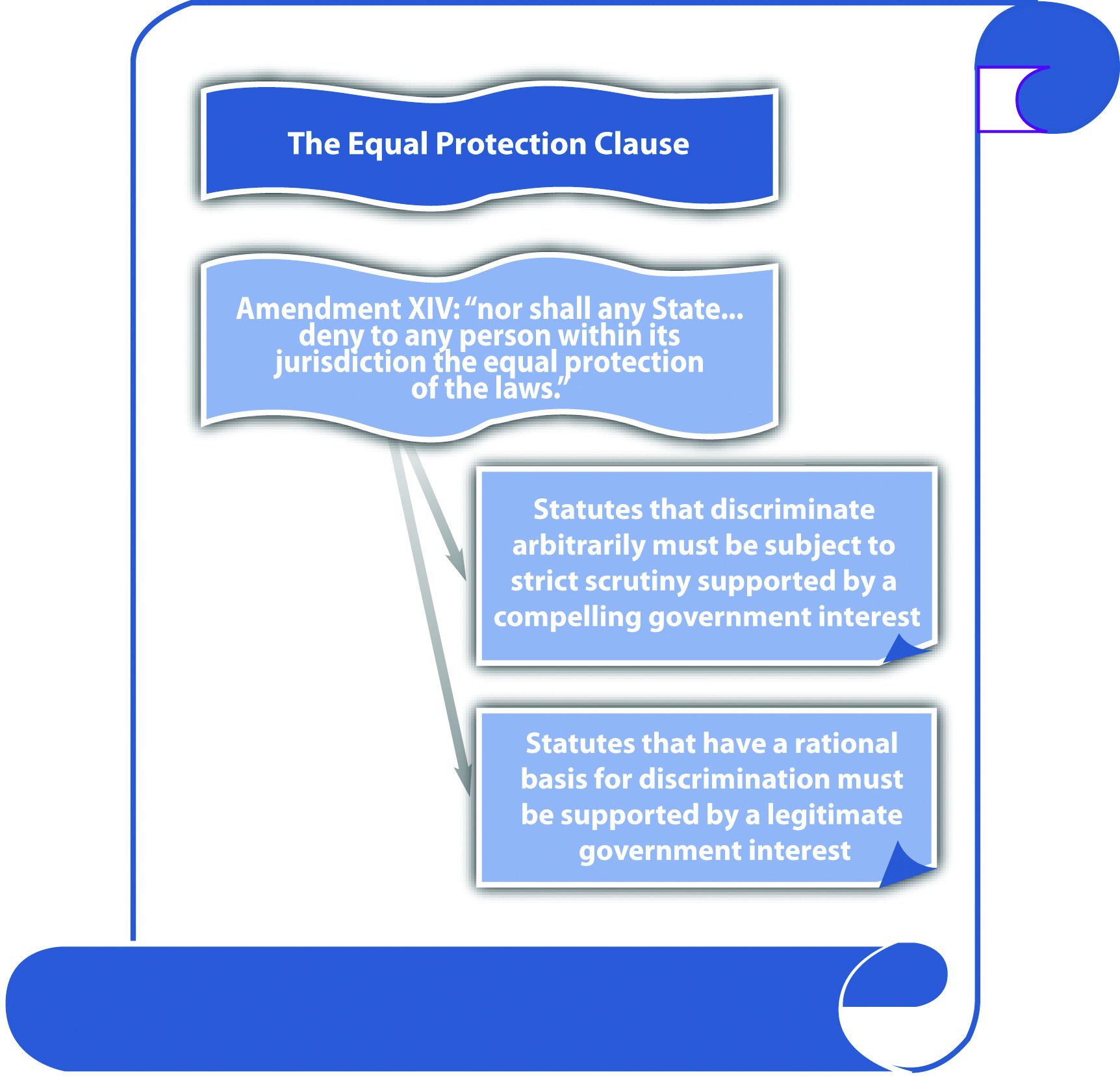

The due process clause states, “No person shall…be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” The due process clause in the Fifth Amendment applies to federal crimes and federal criminal prosecutions. The due process clause is repeated in the Fourteenth Amendment, which guarantees due process of law in state criminal prosecutions. The Alaska Constitution has a nearly identical provision, as do most states. See Alaska Constitution, Art. 1, §7.

Due process is a concept that all persons are entitled to “procedural justice” whenever they are threatened with the loss of life, liberty, or property at the hands of the government. It requires that government provide a mechanism to all persons to ensure that it acts justly, fairly, and reasonably. Due process exists without the need for individual action.

There are two types of due process: substantive and procedural. Substantive due process protects individual liberty and the unreasonable loss of substantive rights, such as the right to speak freely and the right to privacy. Substantive due process prohibits government action that shocks our collective conscience or interferes with our basic concept of ordered liberty. Procedural due process guarantees a fair process in connection with any deprivation of life, liberty, or property at the hands of the government. Procedural due process also ensures that individuals have notice and an opportunity to be heard. Both substantive and procedural due process ensure that individuals are not denied their life (capital punishment), liberty (incarceration), or property (forfeiture) arbitrarily.

Due process, like all constitutional rights, is not limitless. The government may interfere with a person’s individual liberty if the government’s actions are necessary for an ordered society. This balancing test requires the court to assess the quality of the right impacted and the importance of the government’s conduct.

Chase v. State, 243 P.3d 1014 (Alaska App. 2010)

The following case, Chase v. State, demonstrates how courts balance the competing interests involved in government regulation. Although Chase discusses the right to personal autonomy as guaranteed by the Alaska Constitution, the Court analyzed the importance of the government’s regulation when determining the constitutionality of a particular statute.

243 P.3d 1014

Court of Appeals of Alaska.

Steven L. CHASE, Appellant,

v.

STATE of Alaska, Appellee.

No. A–10433.

Dec. 3, 2010.

Rehearing Denied Dec. 30, 2010.

OPINION

MANNHEIMER, Judge.

Steven L. Chase was driving in Fairbanks when a state trooper pulled him over because Chase was not wearing his seatbelt. During this traffic stop, the officer discovered that Chase should not have been driving at all; Chase’s driver’s license was canceled. Chase was subsequently convicted of driving with a canceled driver’s license and driving without his seatbelt fastened. He appeals his convictions, arguing … why his convictions are unlawful.

Chase … argues that Alaska’s seatbelt law is unconstitutional because it is an unjustified infringement of the rights of personal autonomy and liberty guaranteed by Article I, Section 1 of the Alaska Constitution.

…

For the reasons explained here, we conclude that … Chase’s claims [have no] merit, and we therefore affirm his convictions.

Whether Alaska’s seatbelt law infringes the rights of personal liberty, autonomy, and privacy guaranteed by the Alaska Constitution.

We first address Chase’s argument that the seatbelt law is unconstitutional as a general matter. Chase contends that whatever governmental interest there may be in having people wear seatbelts is outweighed by the rights of personal liberty and autonomy guaranteed by Article I, Section 1 of the Alaska Constitution.

Article I, Section 1 of our state constitution declares that “all persons have a natural right to life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness, and the enjoyment of the rewards of their own industry”. In Breese v. Smith, 501 P.2d 159, 168–172 (Alaska 1972), the Alaska Supreme Court interpreted this provision as guaranteeing a certain level of personal autonomy, and as creating a sphere of personal activities and choices that are presumptively immune from government interference or regulation.

Chase argues that Article I, Section 1 protects his right to travel without police interference, his right to personal privacy, and his right to be free from unreasonable seizure.

We are not convinced that Article I, Section 1, standing alone, should necessarily be interpreted to protect all three of the interests that Chase has identified (right to travel, right to privacy, and right to be free of unreasonable seizure)—since two of these interests (privacy, and the right to be free from unreasonable seizure) are explicitly covered by other provisions of our state constitution. Article I, Section 22 guarantees a right of privacy, while Article I, Section 14 prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures. But in any event, we acknowledge that Chase has identified three constitutionally protected interests.

Chase contends that a person’s decision whether to wear a seatbelt is a personal and private choice akin to a person’s choice of hairstyle—a choice that the Alaska Supreme Court declared to be protected under Article I, Section 1 in Breese v. Smith. Chase further argues that the government has no significant interest in making people wear seatbelts when they drive (or ride in) motor vehicles. Chase contends that the seatbelt law has not made any discernible improvement in public safety, and he further contends that the Alaska Legislature’s main motivation for enacting this law was to make sure that Alaska remained eligible for federal highway funds.

However, the record shows that when the legislature first enacted the seatbelt law, the legislature was presented with ample testimony and documentary evidence indicating that the law would increase seatbelt use, would prevent injuries, and would save lives and money. As a general rule, it is not an appellate court’s role to strike down legislation simply because one might reasonably argue that the legislation was misguided, or simply because it appears that legislation may not have accomplished all of its intended goals. As this Court explained in Dancer v. State:

We may not concern ourselves with the wisdom of legislation. Our role is much more modest. We evaluate the legislation to determine whether it contravenes any prohibitions in the constitution. If it does not, we must uphold the legislation. Policy arguments advocating changes to constitutional legislation must be addressed to the legislature, not the courts.

715 P.2d 1174, 1176 (Alaska App.1986).

This leaves Chase’s argument that, whatever legitimate government interest there might be in having people wear seatbelts, that interest is outweighed by the individual’s interest in personal autonomy and privacy. But the Alaska Supreme Court rejected a similar “personal privacy” argument in Kingery v. Chapple, 504 P.2d 831, 835–37 (Alaska 1972), a case in which the supreme court upheld the constitutionality of Department of Public Safety regulations that required motorcycles to have various types of safety equipment, and which required motorcycle riders to wear a helmet.

In rejecting this privacy claim, the supreme court distinguished its earlier decision in Breese v. Smith (dealing with the government’s attempted regulation of a student’s hairstyle choice). The supreme court declared that the challenged motorcycle regulations did not constitute an “invasion of privacy” because those regulations were supported by “compelling state interests in providing for [the] safety of the traveling public”. Kingery, 504 P.2d at 835 n. 6.

When the seatbelt law was under consideration by the legislature, several highway safety experts told the legislature that a seatbelt law which authorized police officers to stop motorists for not wearing seatbelts was an effective measure for reducing the number of deaths and serious injuries from highway accidents. Chase has failed to offer a persuasive rebuttal to that testimony.

For these reasons, we reject Chase’s argument that Alaska’s seatbelt law unlawfully infringes the rights of personal liberty, autonomy, and privacy guaranteed by the Alaska Constitution.

[…]

Conclusion

The judgement of the district court is AFFIRMED.

Notice that the court was obligated to balance the competing interests involved – that is, it had to balance society’s interest in saving lives and money against an individual’s right to be free from governmental interference. The court was unwilling to question the wisdom of a particular law and instead focused on the reasonableness of the interference.

Ask yourself if the courts should be providing such deference to the legislature. How would such deference be applied to a “mask mandate” issued via an Emergency Order by a local government’s mayor as we saw during the Covid-19 global pandemic? Do you think a court would engage in a different analysis?

Void for Vagueness

A statute is void for vagueness if it uses words that are indefinite or ambiguous. A void for vagueness challenge attacks the wording of a statute under the due process clause. Statutes that are not precisely drafted do not provide notice to the public of exactly what kind of behavior is criminal. In addition, and more importantly, they give too much discretion to law enforcement and are unfairly enforced. See e.g., U.S. v. White, 882 F.2d 250, 252 (7th Cir. 1989). To violate due process, a statute must be so unclear that “men of common intelligence must guess at its meaning.” See Connally v. General Construction Co., 269 U.S. 385, 391 (1926). All criminal statutes must give a person of ordinary intelligence fair notice that his or her conduct is forbidden. Note that “person of ordinary intelligence” is measured from the perspective of a reasonable, hypothetical person, not necessarily whether the accused understood the particular statute.

Example of a Statute That Is Void for Vagueness

A state legislature enacts a statute that criminalizes “inappropriate attire on public beaches.” Larry, a law enforcement officer, arrests Kathy for wearing a two-piece bathing suit at the beach because, in his belief, women should wear one-piece bathing suits. Two days later, Burt, another law enforcement officer, arrests Sarah for wearing a one-piece bathing suit at the beach because, in his belief, women should not be seen in public in bathing suits. Kathy and Sarah can attack the statute as being void for vagueness. The term “inappropriate” is unclear and can mean different things to different people. It gives too much discretion to law enforcement, is subject to uneven application, and does not give Kathy, Sarah, or the public adequate notice of what behavior is criminal.

Overbreadth

A statute is overbroad if it criminalizes both constitutionally protected and constitutionally unprotected conduct. This challenge is different from void for vagueness, although certain statutes can be attacked on both grounds. An overbroad statute criminalizes too much and needs to be revised to target only conduct that is outside the Constitution’s parameters.

Example of an Overbroad Statute

A state legislature enacts a statute that makes it criminal to photograph “nude individuals who are under the age of eighteen.” This statute is probably overbroad and violates due process. While it prohibits constitutionally unprotected conduct, such as taking obscene photographs of minors, it also criminalizes First Amendment protected conduct, such as photographing a nude baby.

Figure 3.3 – The Federal Due Process Clause

The Equal Protection Clause

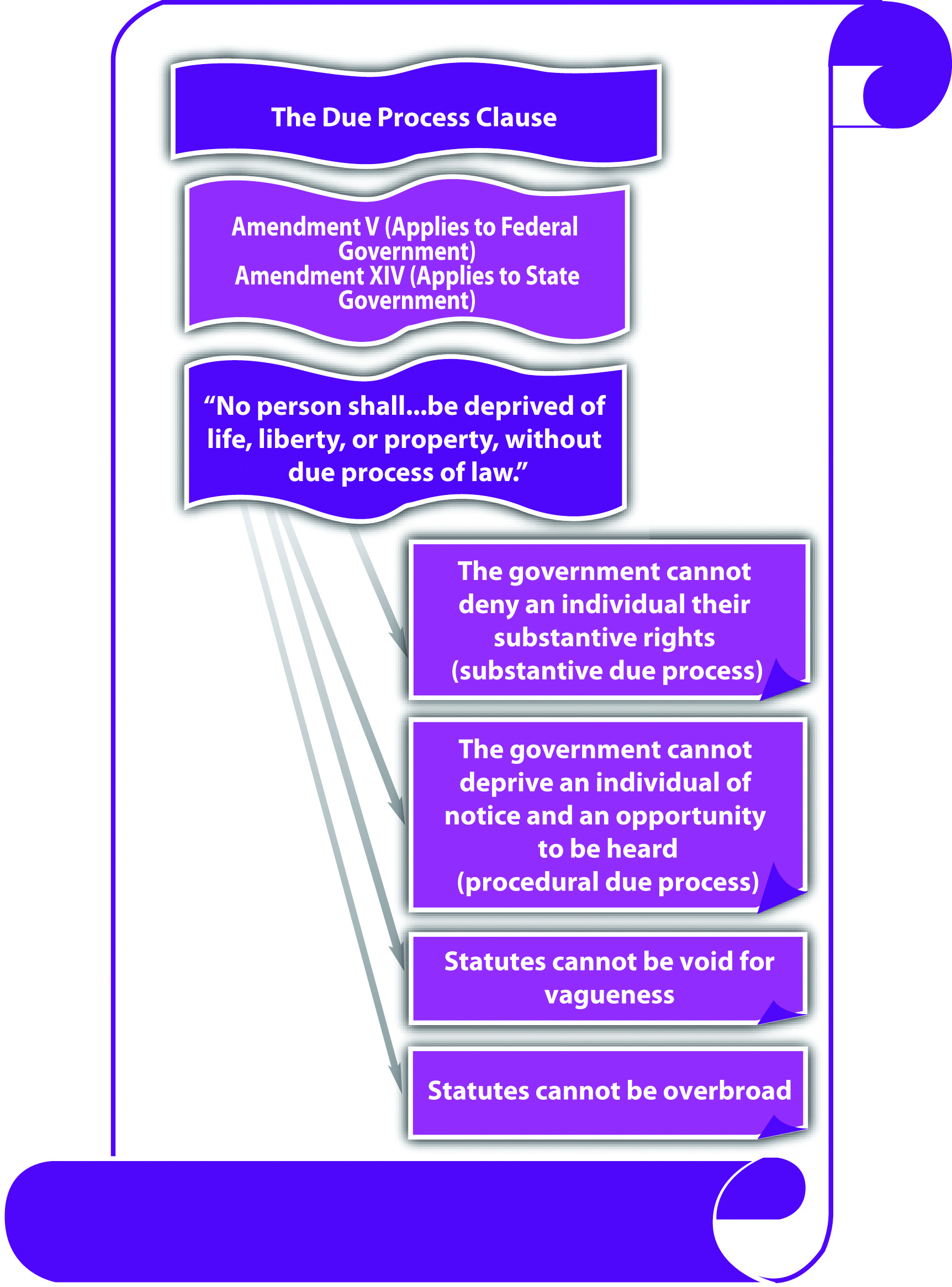

The Fourteenth Amendment states in relevant part, “nor shall any State…deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” The equal protection clause applies to state government. State constitutions generally have a similar provision. Alaska Constitution, Art. I, § 1. The equal protection clause prevents a state from enacting criminal laws that discriminate in an unreasonable and unjustified manner. The Fifth Amendment due process clause prohibits the federal government from discrimination if the discrimination is so unjustifiable that it violates due process of law. See Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497, 498-99 (1954).

To be clear: not all governmental discrimination is prohibited; instead, the government may not impermissibly discriminate. Whether the government impermissibly discriminated against a person depends on the class of persons targeted for special treatment. In general, court scrutiny is heightened according to a sliding scale when the subject of discrimination is an arbitrary classification. Arbitrary means random and often includes characteristics an individual is born with, such as race or national origin. The most arbitrary classifications demand strict scrutiny, which means the criminal statute must be supported by a compelling government interest. Statutes containing classifications that are not arbitrary must have a rational basis and be supported by a legitimate government interest.

Criminal statutes that classify individuals based on their race must be given strict scrutiny because race is an arbitrary classification that cannot be justified. Modern courts do not uphold criminal statutes that classify based on race because there is no government interest in treating citizens of a different race more or less harshly. See generally, Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967).

Criminal statutes that have a rational basis for discrimination and are supported by a legitimate government interest can discriminate, and frequently do. For example, criminal statutes punish felons more severely when they have a history of criminal behavior and are supported by the legitimate government interests of specific and general deterrence and incapacitation. See e.g., Lapitre v. State, 233 P.3d 1125, 1128 (Alaska App. 2010). Note that the basis of the discrimination – a criminal defendant’s status as a convicted felon – is rational, not arbitrary like race. Although these statutes discriminate, they are constitutional pursuant to the equal protection clause.

Figure 3.4 The Federal Equal Protection Clause