The Purposes of Punishment

“Laws without enforcement are just good advice.”

Quote often attributed to Abraham Lincoln

The primary purpose of criminal law is punishment. Through the enforcement of criminal law, society seeks to hold offenders accountable for their individual misdeeds, protect society, and change future behavior. Criminal punishment seeks to balance these competing principles: on one hand, the idea of reformation – the offender should be reformed and rehabilitated. On the other hand, society has a vested responsibility to protect the public. These twin goals are constantly in conflict.

Historically theories of punishment have proposed five purposes for criminal sanctions: deterrence, incapacitation, rehabilitation, restitution, and retribution. Taken collectively, these principles highlight the tension of criminal sanctions: to successfully reduce recidivism (that is, reduce the likelihood a particular offender will re-offend) and keep society safe, but also meaningfully reintegrate the offender into society.

Specific and General Deterrence

Deterrence aims to prevent future crime by frightening the defendant or the public. The two types of deterrence are specific and general deterrence. Specific deterrence applies to an individual defendant. When the government punishes an individual defendant, he or she is theoretically less likely to commit another crime because of fear of another similar or worse punishment. General deterrence, on the other hand, applies to the public at large. When the public learns of an individual defendant’s punishment, the public is theoretically less likely to commit a crime because of fear of the punishment the defendant experienced. With general deterrence, the purpose of the sanction is not necessarily to punish the individual defendant, but instead to make an “example” out of the defendant to deter others from committing a similar offense. When the public learns, for instance, that an individual defendant received a life sentence for the crime of murder, this knowledge hopefully inspires a deep fear of criminal prosecution and deters others from committing murder.

Incapacitation

Incapacitation (sometimes referred to as isolation) prevents future crime by removing the defendant from society. Incapacitation is society’s recognition that some offenders cannot be deterred or rehabilitated. The rationale for incapacitation is an acknowledgment that, at least for the time the person is incarcerated, the person will not harm other members of the community. Incapacitation can include incarceration, house arrest, or capital punishment. Capital punishment (the death penalty) is the ultimate form of incapacitation, which is why it is considered the most serious punishment available within criminal law. It cannot be undone. We will explore capital punishment in more detail in subsequent chapters, but to date, the Alaska Legislature has not authorized capital punishment (although it has explored the possibility several times).

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation seeks to prevent future crime by reforming a defendant’s behavior. Examples of rehabilitation can include educational and vocational programs, treatment center placement, and counseling. The court frequently combines rehabilitation with incarceration or with probation or parole. Offenders must participate in rehabilitative programs in combination with probation, and in addition to, or instead of, incarceration. Alaska Therapeutic Court is an example of a criminal sanction that primarily focuses on rehabilitation. Therapeutic courts can operate as an alternative to traditional incarceration and effectively lower recidivism. To learn more about Alaska Therapeutic Courts see www.courts.alaska.gov/therapeutic.

Restitution

The goal of restitution places the emphasizes repairing the harm caused to the victim. Restitution is meant to make the victim or community “whole.” Restitution can include court orders obligating the criminal defendant to pay the victim for any harm suffered. In this vein, restitution may resemble a civil damages award. Restitution can be for physical injuries, loss of property or money, and rarely, emotional distress (in the form of future counseling costs). It can also be a financial reimbursement to cover some of the costs of the criminal prosecution and punishment.

Retribution

The theory of retribution seeks to prevent future crime by demanding a sanction against the defendant regardless of its rehabilitative impact. When victims or society discover that the defendant has been adequately punished for a crime, they may achieve a certain satisfaction that our criminal justice system is working effectively. Retributive theories seek to enhance society’s overall faith in the criminal justice system by eliminating the desire for personal vengeance (in the form of vigilante justice, for example). Retribution seeks to ensure offenders receive a punishment comparable to the seriousness of the underlying crime.

In 1981, the Alaska Supreme Court found that the “use of retribution as a goal of sentencing is inconsistent” with the Alaska Constitution. See Kelly v. State, 622 P.2d 432, 435 (Alaska 1981). Thus, at least in Alaska, a judge may not impose a criminal punishment against a defendant to satisfy society’s need for revenge.

Instead, Alaska recognizes that some criminal punishments are appropriate, not as retribution, but to reflect the community’s condemnation of the behavior and to reaffirm societal norms. Put another way, some circumstances require a substantial punishment (irrespective of how favorable a defendant’s background may be) because the criminal behavior itself represents a serious deviation from societal norms. Punishment is necessary to uphold legal and moral standards.

Keep this distinction in mind as we discuss Alaska’s statutory sentencing criteria next.

Alaska’s Statutory Sentencing Criteria

Once convicted, a defendant faces a criminal sentencing hearing by which the court formally punishes a defendant, normally in the form of incarceration, monetary fines, community supervision, or restitution. Sentencing is an inherently discretionary judicial function, and when imposing a criminal sentence, the sentencing court has tremendous discretion in determining the appropriate sentence.

Alaska, like most states, has codified not only the authorized punishments but also the purposes of criminal punishment to ensure a rational understanding of the imposed criminal sanctions. In the eyes of the law, understanding why punishment is imposed is just as important as understanding what the precise sentence is.

In Alaska, these codified sentencing considerations[1] include:

- The seriousness of the present offense in relation to other offenses

- The defendant’s prior criminal history and the likelihood of rehabilitation

- The need for confinement to prevent harm to the public

- The circumstances of the offense and extent of harm to the victim or danger to public safety or public order

- Deterrence of the offender and others

- Community condemnation and reaffirmation of societal norms

- Restoration of the victim and the community.

These sentencing goals are of constitutional dimension. These principles are included within the Alaska Constitution Declaration of Rights. See Alaska Const. art. I., § 12.

Figure 2.5 Alaska Constitution – Article I, Section 12.

The court is obligated to consider each sentencing factor independently but is free to prioritize factors differently. Notice how these factors highlight a tension between the rights of a criminal defendant and the rights of a crime victim.

The More You Know…

At the time the Alaska Constitution was adopted, Article 1, section 12 read,

Section 12 Excessive Punishment. Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted. Penal administration shall be based on the principle of reformation and the need for protecting the public.

In 1994, in an effort to strengthen crime victims’ rights within the criminal justice system, the Alaska Legislature proposed two constitutional amendments, both surrounding victims’ rights. First, the legislature sought to broaden the principles of criminal administration by amending Art. 1, § 12, to include language regarding victims’ rights. See Figure 1.5. Second, the legislature sought the adoption of a new provision that specifically enumerated the rights of crime victims within the criminal justice system. See Art. 1, § 24.

Both constitutional amendments were overwhelmingly passed during the 1994 general election (86% for adoption; 14% against adoption). As a result, sentencing courts ought to prioritize the need for protecting the public and the rights of the victims over the defendant’s reformation.

Presumptive Sentencing

General punishment decisions are normally left to the legislative branch. Courts rarely second-guess the legislative decision about how to punish. In Alaska, the legislature has adopted a presumptive sentencing scheme in an effort to eliminate unjustified disparity in criminal punishments and attain reasonable uniformity in criminal sentences. AS 12.55.005. Presumptive sentencing, as the name implies, represents the presumed penalty for a “typical” offender who commits the “typical” offense. As you can imagine, what constitutes a “typical offender” or a “typical offense” is subject to significant debate.

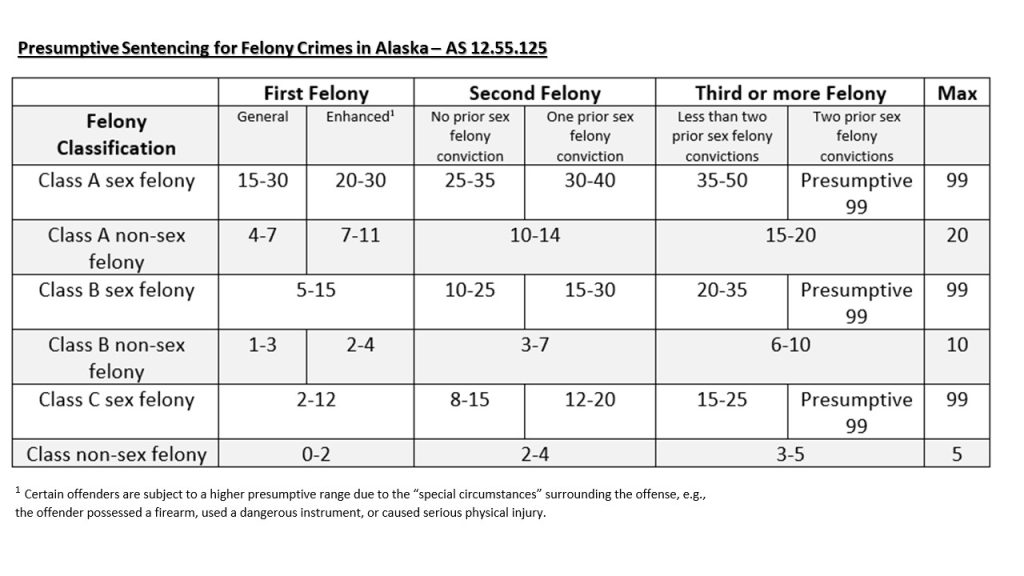

Presumptive sentencing is a sentencing scheme that creates a statutory maximum sentence and then establishes a presumptive prison range within the statutory maximum based on the offender’s criminal history. The presumptive range increases incrementally depending on the offense classification and the offender’s prior felony convictions. Recall that the Alaska Legislature has broken felony crimes into four classifications: Unclassified, Class A, Class B, and Class C. The legislature has established a maximum penalty for each classification. Figure 1.6, below, sets forth a simplified sentencing chart outlining Alaska’s presumptive sentencing scheme. As you can see, an offense being classified as a felony sex offense dramatically increases the applicable sentencing range. AS 12.55.155(i).

Figure 2.6 Alaska Presumptive Sentencing Scheme

Here is an example: let’s assume Sam is convicted of First-Degree Robbery, a Class A felony offense. AS 11.41.500(b). Let’s also assume that Sam has two prior felony convictions. Using the sentencing chart in Figure 1.6, you can see that a Class A non-sex felony offense has a maximum sentence of 20 years. Given that Sam has two prior felony convictions and has been convicted of a Class A felony, he faces a presumptive term of 10 to 14 years. Thus, the sentencing judge’s discretion is constrained by the presumptive sentencing range – the court must impose a term of imprisonment somewhere between 10 and 14 years absent exceptional circumstances.

At sentencing, the judge must impose a definite term of incarceration within the presumptive range unless certain facts – referred to as aggravating and mitigating factors – are established. Sentencing judges may not increase a term of imprisonment above the presumptive range absent an aggravating factor, and likewise, judges may not impose a term of imprisonment below the presumptive range unless a mitigating factor is proven. AS 12.55.155.

Alaska uses a determinate sentencing system, that requires the offender to be placed in the custody of the Alaska Department of Corrections for a definite length of time. If authorized, an offender may be eligible for early release from prison due to mandatory or discretionary parole, both of which are determined post-incarceration by the Alaska Parole Board. Unlike some states, Alaska has not adopted an indeterminate sentencing scheme – that is, a scheme where the sentencing court imposes a sentencing range and the precise term of imprisonment is determined by a separate body, like the parole board, based on its judgment of whether the offender has been rehabilitated or has served an adequate term of imprisonment.

Misdemeanors and unclassified felonies are not subject to presumptive sentencing. Such crimes are generally subject only to a statutory maximum sentence and, if applicable, a statutory mandatory minimum. For these crimes, the sentencing judge may impose any sentence up to the statutory maximum, subject only to any applicable statutory minimum term (or special circumstances) that may apply.

The law treats a “presumptive” sentence much differently than a “mandatory minimum”. A mandatory minimum term is the least possible sentence that can be imposed and represents the legislature’s assessment of how much prison time should be imposed even when the defendant’s background is extremely favorable. A presumptive term, on the other hand, represents the legislature’s judgment as to the appropriate sentence for a typical (average) felony offender (i.e., an offender with a typical background who commits a typical offense).

Take-Away

Criminal laws do not exist in a vacuum, nor do they exist without purpose. Society criminalizes behavior to justify a criminal sanction. Society wants to hold offenders accountable while simultaneously changing future behavior. An in-depth exploration of the various theories of punishment and whether they are effective are beyond the scope of this text. For example, there is good reason to believe that Alaska’s rejection of retribution as a valid sentencing goal is simply a legal fallacy. One central principle of punishment is that sanctions ought to be proportional to the harm caused. Yet, modern retribution theorists argue that society’s over-reliance on notions of deterrence, rehabilitation, and incapacitation is producing much more severe harm than if it simply focused more clearly on “just deserts”. In general, society continues to impose more punitive criminal sentences because it refuses to embrace a desert theory of punishment, and the concept of proportionality that it assumes. That debate, however, is for a different day.

Likewise, sentencing law is a complex area and its mastery is not attainable based solely on the description contained herein. Even though sentencing is a discretionary function, numerous statutes govern (and limit) individual sentencing decisions. This chapter only highlights its overarching schematic design. As discussed, incarceration is not the only sanction available to a sentencing judge. The court has the authority to impose alternatives, such as monetary fines, community supervision, house arrest, community work service, or asset forfeiture. AS 12.55.015. But a complete discussion of sentencing, incarceration, and possible alternatives are beyond the scope of this text and not essential to a functional understanding of substantive criminal law.

That said, as you explore the various acts that constitute criminal behavior consider several broader questions: why does society punish, what are the natural tensions that exist, and what are the competing roles of the different branches of government in criminal punishments?

- In practice, the sentencing factors are routinely referred to as the Chaney criteria, which refer to the legal opinion that originally announced the relevant factors a sentencing court may consider when formulating an appropriate punishment. See State v. Chaney, 477 P.2d 441, 443 (Alaska 1970). The Alaska Legislature subsequently codified the sentencing goals (and others) in AS 12.55.005. ↵