Abuse of Public Office (Official Misconduct)

Bribery is only one form of public servant misconduct. Closely related are the crimes of official misconduct and misuse of confidential information. Unlike bribery, neither official misconduct nor misuse of confidential information require the exchange or attempted exchange of a benefit. Also, unlike bribery, both are misdemeanors.

The crime of official misconduct occurs when a public servant performs (or fails to perform) an act relating to the public servant’s office, knowing that the act constitutes an unauthorized exercise of the public servant’s official function. AS 11.56.850. The statute covers both malfeasance and nonfeasance. In other words, a public servant can commit the crime by acting improperly as well as failing to act properly.

Official misconduct is a specific intent crime. To be guilty, the public servant must act or refrain from acting with a conscious objective to obtain a benefit or to deprive another person of a benefit. Mere negligent behavior or awareness that a person is being harmed or deprived of a benefit will not establish the requisite culpability.

The act must constitute an unauthorized exercise of the public servant’s official functions, and the public servant must know the act is unauthorized. Take “sealed” court records as an example. As a general rule, all court records are open and accessible to the public. See Alaska Admin. Rule 37.5(c)(5). All court staff, however, are trained that when a judge “seals” a court pleading, the pleading is only available for inspection by court order. This normally occurs when the pleading contains highly sensitive, private, or confidential material. See Alaska Admin. Rule 37.5(c)(5). Neither the public nor the parties to the litigation may review the pleading absent express court authorization. If a court clerk, acting with the intent to advantage someone, shows a “sealed pleading” to a person without court permission, the court clerk has committed the crime of Official Misconduct – the clerk committed an act relating to their office knowing that the act constituted an unauthorized exercise of their official function.

A public servant also commits official misconduct if the public servant knowingly fails to perform a duty imposed by law or that is clearly inherent in the nature of their office. Thus, returning to the court clerk example, if the court clerk fails to file a lien against a friend’s property in order to prevent the lienholder from perfecting their security interest, the clerk would be guilty of official misconduct.

Failing to Perform a Duty …

Erin Pohland and Skye McRoberts were close friends and roommates. Pohland was also a lawyer within the Attorney General’s Office advising the Alaska Labor Relations Agency — the agency within the executive branch that dealt with labor union matters. Pohland’s close friend McRoberts worked as a union organizer for the Alaska State Employees Association. The State Employees Association was seeking to unionize the employees of the University of Alaska. In connection with the effort, McRoberts submitted numerous forged employee “interest” cards to the Labor Relations Agency all of which purported to express interest in becoming union members.

The Labor Relations Agency suspected that the interest cards were falsified, so the Agency contacted Pohland for legal advice about how to proceed with an official investigation. Pohland, purportedly acting as the Agency’s lawyer, advised the agency to not investigate McRoberts.

In this case, Pohland committed the crime of Official Misconduct. Pohland failed to provide her client – the Labor Relations Agency – with proper legal advice with the specific intent to benefit her friend, McRoberts. This was an unauthorized exercise of her official duties. (Pohland also committed an ethical violation that resulted in her disbarment from the practice of law.)

To learn more about the case read Pohland v. State, 436 P.3d 1093 (Alaska App. 2019) and In Disciplinary Matter Involving Pohland, 377 P.3d 911 (Alaska 2016).

Misuse of Confidential Information

Misuse of Confidential Information prohibits a public servant from using confidential information learned in public office for their own benefit. AS 11.56.860. Not all information, however, is confidential. The legislature intentionally provides a very strict definition of confidentiality for purposes of criminal liability. Confidential information means information that has been classified by law. AS 11.56.860(b). Public officials are routinely privy to an extraordinary amount of private, sensitive, or even secret information in the regular performance of their job duties. Information deemed “secret”, “classified”, or “private”, is not confidential, unless a specific statute or regulation deems the information “confidential”. A state employee or bureaucrat may not deem certain records confidential simply by decree or executive order. See commentary, Senate Journal Supp. No. 47, at 92 (June 12, 1978). Only the legislature may classify information “confidential”.

Example of Misuse of Confidential Information

As part of their official duties, Alaska law enforcement officers have access to a significant amount of Criminal Justice Information (CJI). CJI contains highly private and sensitive information gathered by local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies, including a person’s criminal history, driver’s license information, and court information. All criminal justice information is confidential by law. See e.g., AS 12.62.160(a) (noting that “criminal justice information and the identity of recipients of criminal justice information are confidential[.]”). The Department of Public Safety (DPS) maintains all CJI for the state in the Alaska Public Safety Information Network (APSIN).

Law enforcement routinely accesses APSIN when conducting investigations. This can include confirming a person’s identity during a simple traffic stop, extensively reviewing a person’s arrest and criminal history during a serious criminal investigation, or determining if a person has an outstanding warrant for their arrest. These are all proper uses of APSIN. However, if a law enforcement officer accesses APSIN for personal reasons – like to retrieve a phone number of a person they would like to date – the law enforcement officer would be guilty of Misuse of Confidential Information.

Misconduct Involving Confidential information

Like public officials, private citizens may not misuse confidential information. To do so is criminal. When a private citizen obtains another person’s confidential information without the other person’s consent, they commit the crime of Misconduct Involving Confidential Information in the Second Degree. AS 11.76.115. Unique to this statute, however, “confidential information” includes not only information classified as confidential by law, but also information encoded on an access device, identification card, or driver’s license. AS 11.76.115. This information is not necessarily “confidential” but is private. AS 11.76.116(c). Thus, if a person surreptitiously obtains private information encoded on an identification card or credit card without the owner’s consent (e.g., “credit card skimming”), the person is guilty of second-degree misconduct involving confidential information. The statute does not require the private information to be used in any nefarious manner. The actus reus of the offense is obtaining the encoded information (not using the information) and the culpable mental state is knowing. The crime is aggravated to misconduct involving confidential information in the first degree if the stolen information is used to commit a crime, obtain a benefit, or unlawfully publish information from a child-victim investigation. AS 11.76.113(A)(1). Both crimes are misdemeanors, similar to the misuse of confidential information discussed above.

Interference with Constitutional Rights

A rarely prosecuted, and distant cousin, to the crimes listed above is the crime of Interference with Constitutional Rights. I say distant cousin because, with one exception, the offense does not require the defendant to be a public official or nor does it relate to private or secret information.

The crime of interference with a constitutional right is intended to protect the exercise of a person’s state constitutional and statutory rights. AS 11.76.110. The statute is modeled after the criminal counterpart to the Federal Civil Rights Act (18 USC § 241, 242). See commentary, Senate Journal No. 47, at 121-22 (June 12, 1978). But even though the statute is modeled after the federal law, the statute excludes violations of federal law. A person who violates a person’s federal constitutional rights could be prosecuted under the federal criminal code by the federal government.

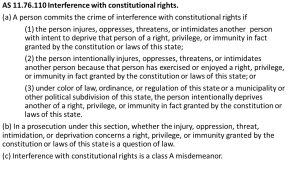

Figure 8.2 – Alaska Criminal Code – AS 11.76.110.

As you can see, a person can violate the statute in three different ways. The first is by injuring or threatening a person with the intent to deprive that person of a right granted by state law or the state constitution. For example, state law guarantees all registered voters the right to vote in a state election. AS 15.07.010. A person who threatens another person with the intent to prevent that person from voting would be guilty of a crime under this statute. AS 11.76.110(a)(1).

The second way the crime may be committed is by retaliating against someone because they have exercised a right granted by state law or the state constitution. For example, if, after leaving the polling place on election day, a person is assaulted because they voted, the crime of Interference with Constitutional Rights has occurred.

Finally, the crime is committed if a person, acting “under color of law”, intentionally deprives another person of a right guaranteed by state law or the state constitution. Thus, if an election official prevents a citizen from voting because the official knows the voter’s political affiliation, the election official could be liable under this section. AS 11.76.110(a)(3).

What constitutes a constitutional or statutory right is a question of law. The court, not the jury, determines whether the right interfered with was protected by the constitution or statute. AS 11.76.110(b). Importantly, the perpetrator need not know that their interference was impacting a protected right. As noted by the drafters, “while the [statute] requires that the defendant act intentionally, use of the phrase ‘in fact’ to describe the protected rights means the defendant need not be aware that the right, privilege, or immunity with which he is interfering is of statutory or constitutional origin.” See commentary, Senate Journal No. 47, at 121-22 (June 12, 1978).

The crime is relatively minor. Like all of the crimes in this section, Interference with a Constitutional Right is a misdemeanor.