Assault (and Battery)

This chapter explores some of the most common crimes against the person, sometimes referred to as violent crimes. All violent crimes involve some element of bodily harm or the threat of bodily harm. Violent crime is simply a broad umbrella term used to group criminal conduct that involves the use of force, fear, or physical restraint. Violent crimes, as a classification, include homicide, robbery, assault, sexual assault, kidnapping, and others.

Violent crimes are generally graded based on the resulting harm. The more serious the resulting harm, the more serious the resulting punishment. Even though this is true of most criminal offenses, society tends to punish violent crimes more harshly than crimes against property or crimes against morality and social order. Convictions for violent crimes tend to expose defendants to more collateral consequences (i.e., collateral barriers resulting from a conviction) than other types of criminal convictions. This is especially true of lower-level violent crimes like misdemeanor assault. For example, federal law prohibits a person convicted of domestic violence misdemeanor assault from possessing firearms or ammunition. See e.g., Voisine v. United States, 579 U.S. 686 (2016). Other non-violent misdemeanor offenses generally do not result in such long-lasting, post-conviction consequences.

Assault and Battery

At common law, assault and battery were separate crimes. Battery referred to the use of force against another person, normally requiring physical contact that resulted in injury or offensive touching. Assault, on the other hand, did not require physical contact. Assault was the apprehension of imminent injury. Assault was committed by either (1) attempting to commit a battery, or (2) by intentionally placing another person in fear of a battery.

Both crimes were considered misdemeanors. The crimes were elevated to felonies depending on the defendant’s mens rea or the instrumentality used. For example, shooting a person in the wrist constituted aggravated battery, since the defendant acted with the “intent to maim” and used a “deadly weapon.” Likewise, a defendant pointing a loaded gun at the victim with the intent to frighten the victim, constituted aggravated assault. See generally Wayne R. LaFave, Substantive Criminal Law §16.3(b) (3rd ed. 2018). Although some jurisdictions continue to use such distinctions, the modern trend is to consolidate assault and battery into the single offense classification of “assault.” Alaska has followed this trend.

Alaska’s Assault Statutes

Alaska’s assault statutes encompass both the infliction of injury and acts that cause the apprehension of injury. Prior to the adoption of Alaska’s revised criminal code, Alaska’s assault laws included the specific crimes of assault and battery; assault with a dangerous weapon; assault with intent to kill; assault with the intent to rape; assault while armed; aggravated assault; and mayhem. The revised criminal code eliminated these specific assault crimes, and instead grouped assault by degree, based on three factors: (1) the defendant’s culpable mental state; (2) the instrumentality of injury; and (3) the result of the assault.

Thus, in every assault, three questions must be considered:

-

- What was the result of the assault – e.g., was someone placed in fear of injury or injured, and if injured, how seriously?

- What was the instrumentality of the assault – e.g., how was the assault committed? Was the assault committed by words or conduct; was a dangerous instrument used; or was the conduct repeated?

- What was the culpable mental state of the offender – e.g., did the defendant act intentionally, recklessly, or with criminal negligence?

Assault Grading

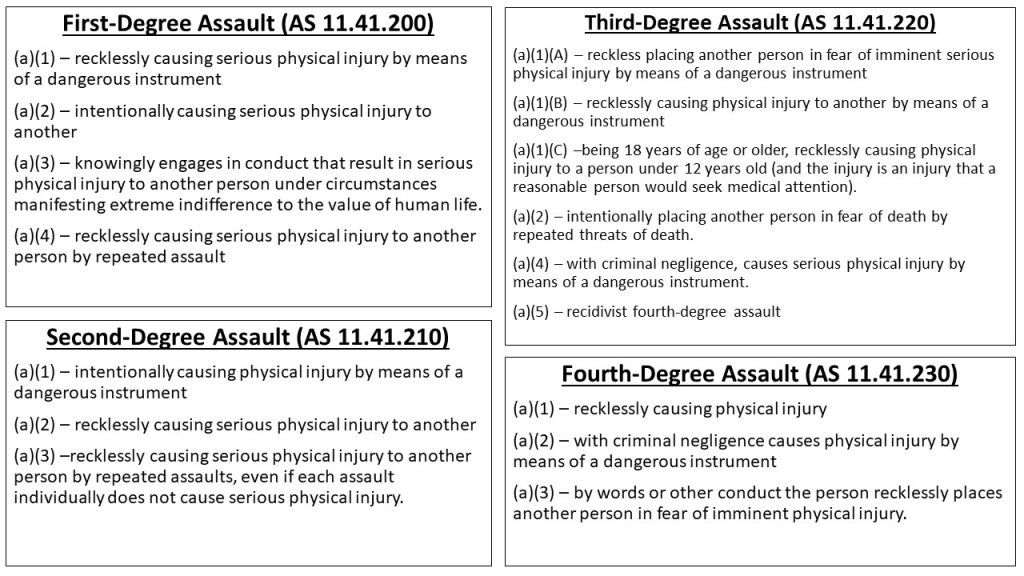

Using these three questions, the criminal code grades assault into four different degrees based on severity. Each degree criminalizes a different combination of the circumstances discussed above – the extent of injury, the instrumentality used (if any), and the defendant’s culpable mental state. For example, assault in the first degree is classified as a class A felony offense and covers the most serious assaults – in terms of resulting harm, instrument used, and culpable mental state (see Fig. 10.1 below). Less serious felony assaults are classified as second- and third-degree assaults depending on the circumstances surrounding the offense. Misdemeanor assaults are classified as assault in the fourth degree.

Figure 6.1 Alaska Criminal Code – Assault Statutes

The code also includes two additional misdemeanor assaults: Assault in the Presence of a Child, which criminalizes physical or sexual assault that occurs in front of minors under the age of 16, and the misdemeanor of Reckless Endangerment, which criminalizes recklessly creating a substantial risk of serious physical injury to another person. AS 11.41.240 and AS 11.41.250(a), respectively.

Extent of Injury (Resulting Harm)

The result of the assault partially dictates what degree of assault was committed. Injury can be viewed on a continuum, with no injury (but the apprehension of injury – i.e., fear) at one end, physical injury in the middle, and serious physical injury at the other end.

Physical injury means a physical pain or an impairment of physical condition. AS 11.81.900(b)(48). Put another way, the assaultive act must cause the victim physical suffering or discomfort. The phrase “impairment of physical condition” is undefined in Alaska law, but likely includes minor injuries, like scratches, small cuts, and bruises even if the injury causes no “pain.”[1] Thus, a punch in the mouth will, under most circumstances, constitute a physical injury, but a simple offensive shove that produces no pain or injury will not.

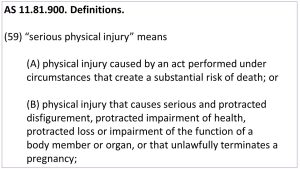

Serious physical injury encompasses more significant injuries. Serious physical injury includes physical injuries that (1) create a substantial risk of death; (2) cause serious and protracted disfigurement; (3) cause protracted impairment of health; (4) cause protracted impairment of bodily organ; or (5) unlawfully terminates a pregnancy. AS 11.74.900(b)(59).

Figure 6.2 Alaska Criminal Code – Serious Physical Injury

Many injuries qualify as serious physical injury, including a broken jaw, a disfiguring cut, a stab or a gunshot wound. The key aspect is whether the injury caused disfigurement or a prolonged recovery. Both are questions of fact for the jury. Thus, a “broken nose” may or may not constitute serious physical injury. It depends on whether the recovery was protracted or whether the victim suffered a serious disfigurement. What constitutes “serious and protracted disfigurement” is for the jury to decide, but it occurs when the injury “detracts from the person’s appearance.” For example, a discolored scar running from a person’s eyebrow to the bridge of their nose likely constitutes serious disfigurement. In contrast, a thin white line scar on the side of the neck likely does not constitute serious disfigurement. See e.g., Saelee v. State, 2011 WL 807391 (Alaska App. 2011).

Notice that serious physical injuries also include physical injuries caused “by an act performed under circumstances that create a substantial risk of death.” AS 11.41.900(b)(57)(A). This definition focuses on the circumstances surrounding the defendant’s actions that caused the physical injury. The victim’s death need not be probable, but the risk of death must be real and substantial. Prompt medical treatment or a victim’s speedy recovery is not the determining factor. Instead, the focus is on the circumstances that caused the injury.

Borozny v. State, 2012 WL 953200 (Alaska App. 2012)

In the following case, the court faced the situation where the victim, although stabbed in the abdomen, fully recovered without significant medical intervention. Does a stab wound to the abdomen constitute “serious physical injury” if the victim was not seriously injured?

2012 WL 953200

Stephen J. BOROZNY, Appellant,

v.

STATE of Alaska, Appellee.

No. A–10634.

March 21, 2012.

MEMORANDUM OPINION AND JUDGMENT

COATS, Chief Judge.

Stephen J. Borozny was convicted by a jury of assault in the first degree for recklessly causing serious physical injury to Francis Katongan by stabbing her with a knife. Borozny argues that the evidence presented at trial was insufficient to show that he caused serious physical injury. He also contends that the State’s argument to the jury about the evidence concerning serious physical injury was improper. We affirm.

Factual and procedural background

On the evening of August 18, 2008, a cabdriver drove three people from the Mush Inn to the Spirits of Alaska liquor store near downtown Anchorage. The party included Borozny and Katongan. When they arrived at the liquor store, Borozny gave Katongan $50 and asked her to purchase some alcohol. She returned with an eighteen-pack of Budweiser, which she gave to Borozny in the front seat of the cab.

Katongan gave Borozny only $12 in change from the purchase. This displeased Borozny. He was “shaking and angry.”

Borozny left the front seat of the cab and walked around to the back seat, where Katongan was sitting. Words were exchanged. He then stabbed Katongan in the abdomen with a knife, picked up the beer, and ran off. Katongan remained near the vehicle, holding her stomach on her lower left side.

Katongan called the police. The driver called 911. The driver spent some time following Borozny as he traveled through the nearby Fairview neighborhood. Borozny was soon arrested nearby. The knife was never found. Katongan was transported by ambulance to Alaska Native Medical Center.

The State charged Borozny with assault in the first degree for recklessly causing serious physical injury to Katongan by stabbing her with a knife. “[S]erious physical injury” is defined as “physical injury caused by an act performed under circumstances that create a substantial risk of death….”

In a jury trial conducted by Superior Court Judge Michael Spaan, Borozny did not dispute that he stabbed Katongan. He defended on the ground that the injuries that he caused did not constitute serious physical injury. The jury rejected his argument and found Borozny guilty. Borozny raises the same argument on appeal.

Why we conclude that the jury could find that Borozny caused serious physical injury

The critical evidence on the issue of whether Katongan suffered serious physical injury was presented through the testimony of Dr. Kevin Stange, an experienced trauma surgeon at Alaska Native Medical Center who had treated Katongan. Dr. Stange testified that the knife wound was two centimeters wide and roughly ten centimeters deep. He said the knife entered Katongan’s left abdominal cavity somewhere between her ninth and tenth ribs. Dr. Stange stated that vital organs in the area of the wound included the stomach, colon, and spleen. Injury to any of these, he testified, had the potential to cause serious harm or death. Fortunately, in Katongan’s case, the knife went up toward her heart and lungs rather than down toward her colon and intestines. Although the knife punctured her chest wall, it did not puncture her lung.

Dr. Stange testified that Katongan was fortunate that the knife went in at an angle that missed her vital organs. Although the wound caused Katongan to lose one-third of her blood volume, this was not sufficient to kill her. Dr. Stange acknowledged that a person who had an injury such as Katongan’s had “an appreciable and significant risk of death, absent medical intervention.” He also noted that the same wound received by someone else, who was older or was not in as good shape as Katongan, “could easily kill them by heart attack, stroke, etc.”

Dr. Stange testified that, although the kind of wound that Katongan received could be dangerous and life-threatening, because she was fortunate and the knife did not strike any vital organs, massive medical intervention turned out to be unnecessary. Ultimately, after taking x-rays and CT scans, Katongan was treated by simply monitoring and observation. Katongan’s body was able to heal, and she ultimately made a good recovery.

Borozny argues that because Katongan was able to recover without any substantial medical intervention, he did not cause serious physical injury. But we rejected this view in James v. State. In James, we stated: “It makes little sense to focus exclusively on the victim’s personal ability to tolerate or recover from an injury, without reference to the seriousness of the risk the injury poses at the time of its infliction.” Whether a defendant commits serious physical injury under AS 11.81.900(56)(A) is determined by whether the defendant caused physical injury “by an act performed under circumstances that create a substantial risk of death.” The question is not the nature of the injury, although that could be relevant to demonstrate the circumstances under which the injury was inflicted, but the circumstances themselves. In the present case, according to Dr. Stange’s medical testimony, when Katongan was brought to the hospital after being stabbed, she faced “an appreciable and significant risk of death.” It was only after significant observation that Dr. Stange was able to discover that Katongan would survive. But the fact that Katongan (and by extension, Borozny) was lucky does not change the fact that the wound that he inflicted created a substantial risk of death. We conclude that there was sufficient evidence for the jury to find that Borozny caused serious physical injury.

[…]

Conclusion

The judgment of the superior court is AFFIRMED.

Instrumentality of Injury

Generally speaking, a defendant who causes injury to another, or places another in fear of injury, using a dangerous instrument is guilty of felony assault. The use of a dangerous instrument elevates an otherwise misdemeanor assault to a felony. Dangerous instrument is broadly defined – it includes anything which, under the circumstances in which it is used, attempted to be used, or threatened to be used, is capable of causing death or serious physical injury. AS 11.81.900(b)(15).

A beer bottle or frying pan could qualify as a dangerous instrument if a person used them in a manner capable of causing serious injury. For example, hitting someone over the head with a frying pan is capable of causing a “protracted impairment of health” (one of the definitions of serious physical injury). But slamming a frying pan down on the stove – even if done in concert with a threat of harm – would not qualify. The focus is on the circumstances surrounding the instrument’s use.

Konrad v. State, 763 P.2d 1369 (Alaska App. 1988).

Even though the definition of a dangerous instrument is broad, it is not limitless. In the following case, the court addresses whether bare hands can qualify as a “dangerous instrument” under the law. As you read Konrad, notice how the court distinguishes between actual weapons and hypothetical weapons.

763 P.2d 1369

Court of Appeals of Alaska.

George A. KONRAD, Appellant,

v.

STATE of Alaska, Appellee.

No. A–2126.

Nov. 10, 1988.

OPINION

BRYNER, Chief Judge.

George A. Konrad was convicted, following a jury trial, of assault in the third degree [and other felonies]. Konrad appeals, arguing that the trial court erred in failing to dismiss his indictment[.] We affirm Konrad’s [other] convictions, but vacate his conviction for third-degree assault.

BACKGROUND

Konrad was indicted for a series of incidents that occurred during the breakup of his marriage to Luann Konrad. The indictment charged Konrad with third-degree assault for recklessly causing physical injury to Luann Konrad by striking her on the head and ribs with his hands[.]

ASSAULT IN THE THIRD DEGREE

On May 9, 1986, following a heated argument, George Konrad struck Luann Konrad twice with his hands: once on the head and once on the ribs. Luann Konrad experienced abdominal pain following the assault. Several days later a physician determined that the blow to Luann’s midsection had injured her spleen, causing it to bleed into her abdominal cavity. The injury resolved itself without treatment.

Based on the May 9 incident, the state requested the grand jury to charge Konrad with assault in the third degree. The state proceeded under AS 11.41.220(a)(2), which states that “a person commits the crime of assault in the third degree if that person recklessly … causes physical injury to another person by means of a dangerous instrument.” The state’s theory was that Konrad’s hands were dangerous instruments.

After reading the statutory definition of “dangerous instrument” to the grand jury, the prosecutor stated, in relevant part: “I would instruct you at this time that in the state of Alaska hands or feet can be considered a dangerous instrument under the definition that I have given you of a dangerous instrument.” The grand jury returned a true bill.

Prior to trial, Konrad moved to dismiss the third-degree assault charge, challenging the propriety of the prosecutor’s instruction to the grand jury. The superior court denied Konrad’s motion. At trial, Konrad unsuccessfully moved for a judgment of acquittal on the third-degree assault charge, contending that the evidence was insufficient to establish the use of a dangerous instrument. Konrad now renews these arguments on appeal.

The term “dangerous instrument” is defined in AS 11.81.900(b)(11):

(11) “[D]angerous instrument” means any deadly weapon or anything which, under the circumstances in which it is used, attempted to be used, or threatened to be used, is capable of causing death or serious physical injury.

“Physical injury” and “serious physical injury” are in turn defined in AS 11.81.900(b)(40) and (50):

(40) “[P]hysical injury” means a physical pain or an impairment of physical condition;

(50) “[S]erious physical injury” means

(A) physical injury caused by an act performed under circumstances that create a substantial risk of death; or(B) physical injury that causes serious and protracted disfigurement, protracted impairment of health, protracted loss or impairment of the function of a body member or organ, or that unlawfully terminates a pregnancy.

This court has never squarely decided whether a bare hand can be a “dangerous instrument” within the meaning of these provisions. In Wettanen v. State, we held that a bare foot could qualify as a dangerous instrument under certain circumstances. The evidence there established that Wettanen had kicked another person repeatedly about the face and head, inflicting serious physical injuries. Because the state neglected to establish whether Wettanen was shod when he committed the assault, it was necessary to decide if a bare foot could qualify as a dangerous instrument. We concluded that sufficient evidence had been presented at trial to allow a finding that Wettanen’s foot was a dangerous instrument, even if it was unshod. In reaching this conclusion, we expressly declined to decide whether a bare hand could similarly qualify as a dangerous instrument, noting that the cases from other jurisdictions on the issue are in conflict.

Since deciding Wettanen, we have had no occasion to resolve this issue. In at least one case, however, we have assumed that a hand might qualify as a dangerous instrument in some situations.

For the purpose of deciding the present case, we may likewise assume that there is no categorical prohibition against a hand being deemed a dangerous instrument under the definition set forth in AS 11.81.900(b)(11). Our prior cases nevertheless firmly establish that the question of whether a hand qualifies as a dangerous instrument in any given case must be answered by examining the precise manner in which the hand is actually used.

The need to focus on the specific circumstances of each case derives from the definition of “dangerous instrument.” While the statutory definition encompasses “anything” that is capable of causing death or serious physical injury, the express language of the statute requires that an instrument’s potential for causing death or serious physical injury be assessed in light of “the circumstances in which it is used, attempted to be used, or threatened to be used.” AS 11.81.900(b)(11). It is the actual use of the instrument in each case that must be considered, not abstract possibilities for use of the instrument in hypothetical cases.

We emphasized this point in Wettanen, cautioning that “every … blow, even if it causes serious injury, will not automatically be an assault with a dangerous instrument.” We pointed out that the inquiry must focus on the vulnerability of the victim and the specific nature of the assault in each case. In this regard, we emphasized that “the requirement of a dangerous instrument serves to shift the focus of the trier of facts’ attention from the result (physical injuries), which in any given case may have been unforeseeable to the defendant at the time the assault was committed, to the manner in which the assault was committed.”

We elaborated on Wettanen in Carson v. State, […], a case involving an analogous situation. In that case, police officers performing a misdemeanor arrest subdued Carson by kicking him in the groin and unleashing a police dog, which bit Carson on the legs and buttocks until he ceased struggling. At issue was whether the officers’ actions amounted to “deadly force.” The applicable statute defined “deadly force” to include any force used under circumstances that “create a substantial risk of causing death or serious physical injury.”

We found that the evidence in Carson did not support a finding that deadly force had been used. In reaching this conclusion, we emphasized the need to focus on the actual risk of serious physical injury posed in the specific case, rather than on the abstract possibility of serious physical injury under other, hypothetical circumstances. We said, in relevant part:

Although we can certainly conceive of cases in which specific testimony describing a kick to the groin or an attack by a dog would support the inference that a substantial risk of death or serious physical injury was created, we are unwilling to conclude that testimony establishing no more than the unadorned fact of a kick to the groin or an attack by a police dog is per se sufficient to create a jury question as to the use of deadly force. The issue is not one to be resolved in the abstract. There must, at a minimum, be some particularized evidence from which a reasonable juror could conclude that a substantial risk of serious physical injury was actually created in the specific case at bar.

The issue is analogous to one we considered in Wettanen v. State. There, we held that, while any object, including an unshod foot, that was capable of inflicting serious physical injury might qualify under the broad statutory definition of “dangerous instrument,” the actual determination of whether a dangerous instrument was used must be made on a case-by-case basis, based on the totality of the circumstances surrounding the actual use of the object in question.

When read together, Wettanen and Carson stand for the proposition that, before a hand may be deemed a “dangerous instrument,” the state must present particularized evidence from which reasonable jurors could conclude beyond a reasonable doubt that the manner in which the hand was used in the case at issue posed an actual and substantial risk of causing death or serious physical injury, rather than a risk that was merely hypothetical or abstract.

Obviously, whenever serious physical injury does in fact occur, there will be prima facie evidence to support a finding that a dangerous instrument was used. Conversely, when serious physical injury does not occur, other case-specific evidence must be adduced to establish that the risk of such injury was both actual and substantial, even though it did not in fact occur.

The facts of the present case are problematic when viewed in light of this analysis. We consider initially the grand jury proceedings. The state did not contend below, and it does not argue on appeal, that Luann Konrad suffered serious physical injury when Konrad struck her with his hands. In presenting its case to the grand jury, the prosecution instructed that “under Alaska law hands or feet can be considered dangerous instruments.”

The ambiguity of this instruction is troublesome. While it might be taken to indicate that the decision as to whether Konrad’s hands were dangerous instruments was a factual one to be made by the grand jury, it might as readily be taken to indicate that there was no need at all for the grand jury to consider the issue, since it was settled as a matter of Alaska law. In our view, the giving of this instruction raises a serious question as to whether the grand jury in Konrad’s case ever actually determined, as a factual matter, whether Konrad used his hands in a manner capable of inflicting death or serious physical injury.

In any event, even without the ambiguous instruction, we believe that the circumstances of the present case would have been sufficiently unique to require a specific admonition to the grand jury concerning the manner in which it was required to determine whether a dangerous instrument had been used.

We recognize that the grand jury was appropriately instructed on the statutory definitions of “dangerous instrument,” “physical injury,” and “serious physical injury.” Nevertheless, when, as in the present case, the defendant is alleged to have used a dangerous instrument that was not a “deadly weapon” and that did not actually inflict death or serious physical injury, the possibility that the grand jury might decide the instrument’s potential for causing injury as an abstract or hypothetical matter is, in our view, sufficiently great to require that an express instruction be given. The instruction should alert the grand jury to the need for it to find, based on the evidence in the case before it, that the defendant used an instrument in a manner that actually created a substantial risk of death or serious physical injury. In view of the lack of an appropriate clarifying instruction and the ambiguity of the instruction actually given, we conclude that the trial court erred in denying Konrad’s pretrial motion to dismiss the count charging him with assault in the third degree.

[…] As we have already indicated, the state does not allege that the evidence established that Konrad inflicted serious physical injury by striking Luann Konrad with his hands. While Luann suffered internal bleeding from the spleen, the condition healed without treatment within a short period of time. No medical evidence was adduced to establish that Luann’s condition verged on becoming more serious or that a blow to the ribs similar to that inflicted by Konrad actually posed a risk of inflicting more severe injuries to the spleen or to other internal organs.

Apart from Luann Konrad’s testimony that Konrad’s hand was in a fist when he struck her, there is nothing in the record to establish that the manner in which Konrad used his hands was inordinately violent or particularly calculated to inflict serious physical injury. No evidence was offered to suggest that Konrad had received martial arts training or that he was otherwise skilled in using his hands to inflict physical injury.

Other than the fact that Konrad had awakened Luann Konrad shortly before he assaulted her, there was no evidence to suggest that she was especially susceptible to incurring a serious physical injury. Although it can be inferred that Luann would have been better able to ward off Konrad’s blows and to prevent the injuries that she did receive had she not recently been asleep, nothing in the evidence establishes that she was vulnerable to suffering injury more serious than that actually inflicted merely because she had been sleeping and was caught off guard by Konrad’s assault.

In arguing that the evidence was sufficient to support a finding that Konrad’s hands were dangerous instruments, the state notes that, after the assault, Konrad offered to take Luann to the doctor when he got back from work. The state contends that this evidence reflects upon the seriousness of Konrad’s assault and could legitimately be relied on by the jury.

To the extent that Konrad’s offer of assistance betrayed his awareness that he had assaulted Luann Konrad with sufficient force to inflict injuries requiring medical treatment, the state is correct. However, the evidence does nothing to indicate that Konrad believed he had inflicted serious physical injury, as opposed to nonserious physical injury. Consequently, the evidence fails to establish, either directly or inferentially, that his assault created an actual and substantial risk of serious physical injury.

In ruling on the sufficiency of the evidence at trial, we must view the evidence and the inferences arising therefrom in the light most favorable to the state to determine whether reasonable jurors could conclude that the defendant’s guilt was established beyond a reasonable doubt. Applying this standard to the present case, we conclude that insufficient evidence was adduced to support Konrad’s conviction of third-degree assault. In our view, the evidence cannot justify a finding that Konrad’s hands qualified as dangerous instruments. On the record of the present case, a conclusion that Konrad’s hands were capable of causing death or serious physical injury under the circumstances in which they were actually used—that is, that they actually created a substantial risk of death or serious physical injury to Luann Konrad—would be wholly speculative.

Were we to find sufficient evidence in this case to support a conclusion that Konrad’s hands were dangerous instruments, a similar conclusion would be justified in virtually every case involving blows struck with fists that inflicted some physical injury. We conclude that the trial court erred in denying Konrad’s motion for a judgment of acquittal as to the charge of assault in the third degree.

[…]

The conviction for assault in the third degree is VACATED. This case is REMANDED to the superior court, with directions to amend the judgment accordingly.

You be the Judge …

In 2015, Dulier and John Sears got into an argument when they were smoking cigarettes outside the Rendezvous Bar in Juneau. Sears and Dulier had a heated exchange before Sears went back inside.

Later, Sears and another patron went outside again. Dulier, who was still outside, stepped up to Sears, held a flare gun to Sears’s neck, and fired it. A bar patron grabbed Sears by the shoulder just as the flare gun went off, causing Sears to move to the left just before the flare hit him. The flare impacted the front of Sears’s neck, next to his Adam’s apple. The flare ricocheted off Sears’s neck, hit the wall of the bar, and then landed on the bar’s welcome mat, where it sat burning for a moment before another patron kicked it out toward the street. When the officers arrived at the bar, Sears had a “large bloody powder burn” and welt on his neck. After speaking to the police, Sears went to the hospital for treatment. In addition to a bad burn, Sears had a large bruise and a bloody gouge on his neck. He was prescribed antibiotics and a painkiller. After the incident, Sears had a hard time talking, and the inside of his throat was swollen for four or five days.

The prosecution charged Dulier with felony assault for recklessly causing physical injury to Sears “by means of a dangerous instrument.” Based on these facts, do you think there was sufficient evidence that Dulier used a “dangerous instrument” to support an assault conviction? Why or why not? Check your answer at the end of the chapter.

The term dangerous instrument also includes any “deadly weapon.” A deadly weapon includes any knife, axe, club, or explosive. It also includes all firearms, whether loaded or unloaded. The firearm need not be functional to constitute a “deadly weapon.” AS 11.81.900(b)(27). Thus, pointing an unloaded, non-functional pistol at a person in a threatening manner qualifies as felony assault, even though the weapon – factually – is incapable of causing injury.

Manual Strangulation (Hands as a Dangerous Instrument)

Any object, including hands, used to obstruct a person’s airway and breathing, constitutes a per se dangerous instrument. AS 11.81.900(b)(15)(B). Strangulation – aka “sleeper holds”, “chokeholds”, or anything that forcibly compresses a person’s airway – is particularly dangerous. Strangulation is highly lethal; unconsciousness may occur within seconds and death within minutes. Further, in the context of intimate partner violence, past strangulation is highly predictive of future violence. Victims of non-fatal strangulation are more than seven times more likely to be the victim of homicide. (Glass et al. 2008[2]).

In 2015, in an effort to make it easier to prosecute perpetrators with felony assault who strangle their victims, the Alaska legislature amended the definition of “dangerous instrument” to include “hands, other body parts, or other objects when used to impede normal breathing or circulation of blood by applying pressure on the throat or neck or obstructing the nose or mouth.” AS 11.81.900(b)(15)(B); SLA 2005, ch. 20, §1.

Under this definition, when a perpetrator strangles their victim (most commonly using their hands), the instrumentality used (e.g., hands) will constitute a “dangerous instrument” as a matter of law. The government is not required to prove that the defendant’s hands (or object used) caused a substantial risk of death. In essence, this alternate definition recognizes that when hands or other objects are used to impede a person’s breathing, the perpetrator is effectively using a deadly weapon.

Note that the alternate definition does not change the result of Konrad v. State, 763 P.2d 1369 (Alaska App. 1988), excerpted above. This definition of “dangerous instrument”, adopted nearly twenty years after Konrad, only applies when the defendant uses their hands or other objects to impede the victim’s breathing. AS 11.81.900(b)(15)(B).

Imminent Fear (or lack thereof)

When the victim is injured, the law focuses on the extent of the injury and the instrumentality used. However, both third-degree assault and fourth-degree assault criminalize fear assault – that is, an act that places a person in “fear of imminent” injury. Compare AS 11.41.220(a)(1)(A) and AS 11.41.230(a)(1). If a defendant places a person in fear of immediate physical injury by words or conduct, then the crime is misdemeanor assault. If a defendant places a person in fear of serious physical injury using a dangerous instrument, the crime is elevated to felony assault. This is the difference between threatening to punch someone in the nose and threatening to shoot someone with a gun. The former is a misdemeanor while the latter is a felony.

Two issues arise in fear assault prosecutions. First, the risk of injury must be imminent. Future, uncertain, or conditional threats are insufficient. The defendant must engage in some physical gesture or specific conduct that reflects an immediate ability to inflict harm. See e.g., Lussier v. Alaska, 2021 WL 2453649 (Alaska App. 2021) (citing Coleman v. State, 621 P.2d 869, 876-77 (Alaska 1980)). Second, the defendant must place the victim in fear. The term “fear”, in this context, means the victim was aware of the threat, not that the victim was scared. This is because not all victims are created equal. Some will cower away, afraid of injury, while others will stand up and fight. The Alaska Court of Appeals describes “fear” as follows:

As used in [the assault statute], the word “fear” does not refer to fright, dread, intimidation, panic, or terror. Rather, a person is “placed in fear” of imminent injury if the person reasonably perceives or understands a threat of imminent injury. The victim’s subjective reaction to this perception is irrelevant. It does not matter whether the victim of the assault calmly confronts the danger or quivers in terror. The question is whether the victim perceives the threat.

See Hughes v. State, 56 P.3d 1088, 1090 (Alaska App. 2002).

The victim must perceive the threat and their apprehension of danger must be reasonable. If the victim is unaware of the defendant’s threatening actions or their apprehension was unreasonable, then an assault was not committed. See e.g., Hodge v. State, 2008 WL 2609662 (Alaska App. 2008). For example, an enraged father is not guilty of assault for throwing a hammer at his infant child since the child cannot be aware of the threat. See e.g., Harrod v. Maryland, 499 A.2d 959, 962 (Md. Ct. Spec. App. 1985). See generally Wayne R. LaFave, 2 Substantive Criminal Law § 16.3(b), at 569 (“It is not enough, of course, to intend to scare the other without succeeding; if the other fails to notice the threatened battery, the threatener, not having succeeded in his plan, cannot be held guilty of assault.”).

Although the victim must be aware of the defendant’s threatening actions, the defendant need not purposely cause apprehension (provided the defendant otherwise acts “recklessly”). If a defendant recklessly places a victim in apprehension of injury, even if the defendant is unaware of their own threatening conduct, the defendant is guilty of assault. For example, a drunk driver who nearly strikes a pedestrian, but fortuitously misses the person, is still guilty of felony assault even if the defendant was unaware of the pedestrian. See e.g., State v. Watts, 421 P.2d 124 (Alaska App. 2018).

- I say minor injuries, like scratches, "likely" constitute physical injuries under Alaska law because the Alaska Court of Appeals has refused to expressly answer the question. See Eaklor v. State, 153 P.3d 367, 370 n.3 (Alaska App. 2007). However, in Eaklor, the Court suggested that such minor injuries would qualify. ↵

- See Non-Fatal Strangulation Is an Important Risk Factor for Homicide of Women, Glass N., Laughon K., Campbell J., Block C.R., Hanson G., Sharps P.W., Taliaferro E. (2008), Journal of Emergency Medicine, 35 (3), pp. 329-335. ↵