Attempt

Criminal law contains three inchoate crimes – attempt, solicitation, and conspiracy. Inchoate crimes are, by definition, incomplete or anticipatory crimes. The law imposes criminal liability on individuals even though the “would-be” criminal was never successful in achieving their intent – a completed crime. All inchoate offenses are specific intent crimes – that is, all inchoate crimes require a specific intent to carry out the underlying criminal offense. Compare attempt crimes, which never result in a finished criminal offense, to solicitation and conspiracy, which may result in separate, completed crimes.

We punish individuals who commit inchoate crimes because of the danger they pose. Even though criminal preparation may not result in a tangible, immediate harm, anticipatory criminal behavior increases the likelihood that the ultimate harm will occur. This preparation is dangerous in its own right. Society should not have to wait until harm occurs before intervening. Put another way, waiting until a crime is completed is unnecessarily harmful. Law enforcement should proactively investigate criminal behavior and avert injury to victims or property where possible. If a defendant could not be apprehended until a crime was accomplished, law enforcement would be forced to stand by and watch harm occur. Punishing inchoate crimes also prevents future criminal activity. If a criminal is permitted to continue trying to achieve their objective, free from any criminal consequences, they would not be deterred. Crime should not be like riding a horse; we should not encourage criminals to get back on if they fall off.

However, there is a fine line between punishing anticipatory criminal activities and punishing criminal thoughts. Remember, criminal thoughts – standing alone – are never criminal. Society does not punish the “guilty mind.” Simply dreaming about killing your boss is not unlawful. Action must occur. The difficulty is ascertaining the level of progress necessary to impute criminal responsibility. And, although the law requires a specific purpose to commit the target offense, jurisdictions have struggled to define the difference between thoughts and actions.

History of Attempt

The crime of attempt punishes the unsuccessful effort to commit the crime. But the crime of attempt is a relatively recent legal development. At early common law, an attempt was not a crime. See Wayne R. LaFave, Substantive Criminal Law §11.2(a) (3rd ed. 2018). The law required the resulting harm to occur. It was not until the late 18th century that courts began to recognize the unnecessary danger the law was encouraging. The first documented case of attempt was Rex v. Scofield, Cald. 397 (1784), in which a servant was convicted of a misdemeanor for attempting to burn down his master’s house with a lighted candle. The doctrine was crystalized in a subsequent case, Rex v. Higgins, 2 East. 5 (1801), upholding an indictment for attempted theft even though the perpetrator was unsuccessful in the intended theft. See LaFave, at §11.2(a). In modern times, nearly every jurisdiction criminalizes attempt, but as you will see, courts and legislatures continue to struggle as to what precisely constitutes an attempt.

Attempt – Voluntary Act (Actus Reus)

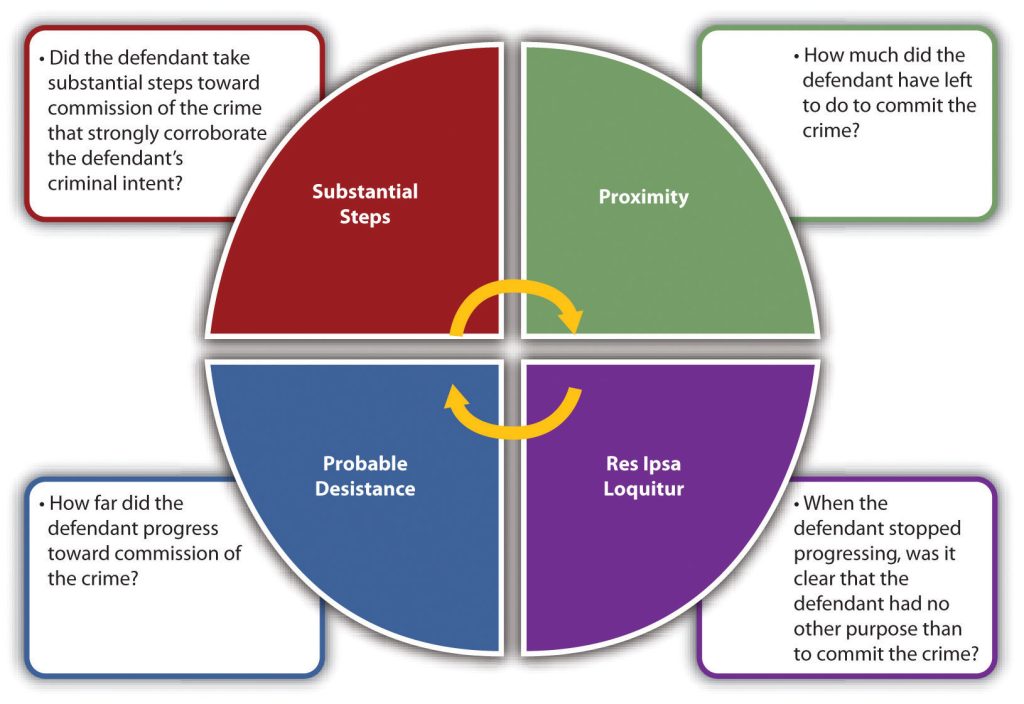

It is helpful to think of the actus reus of attempt on a continuum. On one hand, a person may have isolated, private criminal thoughts, which, without action, are not criminal. On the opposite side, is the completed crime. Attempt falls somewhere in between. Nearly every jurisdiction recognizes that mere preparation is insufficient to establish the actus reus of attempt. A defendant does not commit attempt by merely plotting or planning an offense. The crux of attempt is how close to completing the offense the defendant must get to fulfill the voluntary act requirement. To identify when the crime of attempt is consummated on the continuum, most jurisdictions have relied on one of four tests: (1) the dangerous proximity test, (2) the probable desistance test, (3) the res ipsa loquitur test, and (4) the substantial step test.

Dangerous Proximity Test

The dangerous proximity test measures the defendant’s progress by examining how close the defendant is to completing the offense. The distance measured is the distance between preparation for the offense and successful completion. It is the amount left to be done, not what has already been done, that is analyzed. See generally People v. Rizzo, 246 N.Y. 334 (N.Y. 1927). Generally, the defendant does not have to reach the last step before completion, although many defendants do.

Probable Desistance Test

The probable desistance test examines how far the defendant has progressed toward the commission of the crime, rather than analyzing how much the defendant has left to accomplish. Under this test, the trier of fact must determine whether the defendant’s conduct reached a point where he is unlikely to voluntarily abandon his efforts to complete the crime. Put another way, the conduct constitutes an attempt if, in the ordinary and natural course of events, without interruption from an outside event (like law enforcement), it will result in the crime being completed. See United States v. Manjujano, 499 F.2d 370, 374 (5th Cir. 1974).

Res Ipsa Loquitur Test

Res ipsa loquitur means “the thing speaks for itself.” See e.g., Black’s Law Dictionary (6th ed. 1990). Under the res ipsa loquitur test, also called the unequivocal test, an attempt is committed when the defendant’s conduct manifests a clear intent to commit the crime. The trier of fact must focus on the moment the defendant stopped progressing toward completion of the offense, and determine whether it was clear that the defendant had no other purpose than completing the specific crime. See Hamiel v. Wisconsin, 285 N.E. 2d 639, 665-66 (Wis. 1979).

The Substantial Step Test

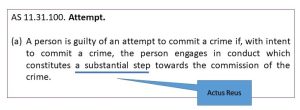

Alaska has adopted the test developed by the Model Penal Code – the substantial step test. This test was developed in response to the large variance between jurisdictions in evaluating the conduct required for attempt. It is intended to clarify and simplify the analysis – simply put, the test asks the trier of fact to determine if the defendant took a “substantial step” towards to completion of the target offense. Take a look at Alaska Statute 11.31.100(a).

Figure 13.1 Alaska Criminal Code – Attempt

To be guilty of attempt, one must engage in conduct that demonstrates a clear, definitive intent to complete the crime. The language recognizes that mere preparation is insufficient. Minimal or preliminary steps, which may be suspicious, are insufficient. The Model Penal Code provides seven examples of actions that constitute a substantial step, as long as they are corroborative of the defendant’s intent: lying in wait; enticing the victim to go to the scene of the crime; investigating the potential scene of the crime; unlawfully entering a structure or vehicle where the crime is to be committed; possessing materials that are specially designed for unlawful use; possessing, collecting, or fabricating materials to be used in the crime’s commission; and soliciting an innocent agent to commit the crime (Model Penal Code § 5.01(2)). To be clear, neither the Model Penal Code, nor Alaska law define a “substantial step”. Instead, the law requires the defendant’s act(s) are “strongly corroborative of the [defendant’s] criminal purpose” – that is, the totality of the circumstances must convincingly demonstrate the defendant’s willingness to commit the crime. See e.g., Avila v. State, 22 P.3d 890, 893-94 (Alaska App. 2001).

The substantial step test is a close cousin to the res ipsa loquitur test. And, unlike the Dangerous Proximity or the Probable Desistence Tests, there is no requirement that the offender be in physical proximity or close to the offense to be held accountable, instead the focus is on whether the person’s intent is clear.

Example of the Substantial Step Test

Kevin wants to rob an armored car that delivers cash to the local bank. After casing the bank for two months and determining the date and time that the car makes its delivery, Kevin devises a plan that he types out on his computer. On the date of the next delivery, Kevin hides a pistol in his jacket pocket and makes his way on foot to the bank. Thereafter, he hides in an alley and waits for the truck to arrive. The truck never arrives. Unbeknownst to Kevin, the delivery was canceled the night before. In the interim, his wife discovered his plan on his computer and called the police. The police arrest Kevin after they observe him enter the alley and begin to wait. In this case, Kevin has committed the criminal act required for attempted robbery. Kevin cased the bank, planned the robbery, showed up on the appointed date and time with a concealed pistol, and hid in an alley to wait for the truck to appear. Kevin’s intent was clear.

Although Kevin is guilty of attempt under the substantial step test, he is probably not guilty under the dangerous proximity test. Given that the armored truck never arrived and would not have arrived (since the delivery was canceled), Kevin was not within proximity to a completed, successful robbery. See generally People v. Rizzo, 246 N.Y. 334 (N.Y. 1927).

Example of Mere Preparation

Remember that merely preparing to commit a criminal offense will not establish the actus reus of attempt. Read the following case, Sullivan v. State, 766 P.2d 51 (Alaska App. 1998) and ask yourself whether there was any real dispute as to what the defendant’s intent was regarding his victims? Why did the court find these actions insufficient to rise to the level of substantial steps?

766 P.2d 51

Court of Appeals of Alaska.

Rodney G. SULLIVAN, Appellant,

v.

STATE of Alaska, Appellee.

No. A–2229.

Dec. 23, 1988.

OPINION

BRYNER, Chief Judge.

Rodney G. Sullivan was convicted, after a bench trial, of attempted sexual abuse of a minor in the second degree, a class C felony. AS 11.41.436(a)(2).

Sullivan … appeals, challenging his conviction for attempted sexual abuse[.] We conclude that there was insufficient evidence to convict Sullivan of attempted sexual abuse[.]

FACTS

In September of 1984, Sullivan was staying in Ketchikan at the house of a friend, who had asked Sullivan to help keep an eye on her three children while she was on vacation for two weeks. During this period, various neighborhood children had been given permission to enter the house and to play with the family dog.

One day while several children were at the house, Sullivan approached D.T., an eight-year-old girl, and offered to “give [her] some money if [she] would be his girlfriend.” She replied, “No.” That same day, Sullivan gave D.T. and another girl, K.W., a note. According to D.T., the note read: “Will you be my girlfriend? Will you kiss me? Will you take off your clothes? Will you get another girlfriend for me?” The note also included boxes for “yes” and “no” responses. Sullivan paid D.T.’s seven-year-old brother, J.T., two dollars to deliver the note. At some point during that day, Sullivan locked J.T. into a room because, according to J.T., Sullivan “wanted to tell [D.T.] a nasty letter.” Sullivan also told J.T. that he wanted to invite D.T. “and a whole bunch of other people” to a party, and that “the only parties he had is bad parties” with girls. D.T. received at least ten or twelve other notes from Sullivan while she was at his house that day. She did not remember what the other notes said.

K.W. remembered that D.T. read her a note that Sullivan had given them. The note asked, “Do you want to be my girlfriend?” and stated, “I’ll give you a thousand dollars if you do.” K.W. also remembered that Sullivan asked the girls if they would take off their clothes in front of him.

H.T., a nine-year-old girl, was also at Sullivan’s house with D.T., K.W., and J.T. She read the note Sullivan gave to D.T. and K.W. H.T. recalled the four questions that D.T. described, although she added that there was a fifth question, which she could not recall. H.T. heard Sullivan ask K.W. and D.T. to take off their clothes “a lot of times.” She recalled that Sullivan showed the children pictures of “naked ladies” in Playboy magazine and that he gave the three girls “tests” with such questions as, “Will you go to bed with me?” and, “Will you marry me?”

On a later day, D.T. received another note from Sullivan, this time delivered to her by J.T. at home. The note said that if D.T. agreed to answer “a lot of questions, [Sullivan] would have a party.” D.T. destroyed the note.

D.T. subsequently reported the notes to her mother, who notified the Ketchikan police. During police questioning, Sullivan acknowledged the incidents and attempted to reconstruct his original note to D.T. The reconstructed note read:

I really like you a lot. I would be proud to have you as my girlfriend. So I’m going to ask you some questions. Will you go with me? Will you kiss me? Will you let me feel private parts of your body? Will you take off all of your clothes in front of me? And will you let me kiss the private parts of your body? I really hope you do some of these thing in the questions.

Sullivan was subsequently indicted on one count of attempted sexual abuse in the second degree.

[…]

SUFFICIENCY OF EVIDENCE TO SHOW ATTEMPTED SEXUAL ABUSE OF A MINOR IN THE SECOND DEGREE

Sullivan argues that there is insufficient evidence to support his conviction for attempted sexual abuse.

[…]

Alaska Statute 11.31.100(a) sets out the elements of an attempt:

[A] person is guilty of an attempt to commit a crime if, with intent to commit a crime, the person engages in conduct which constitutes a substantial step toward the commission of that crime.

In order to constitute a “substantial step,” conduct must go beyond mere preparation. Whether an act is merely preparatory or is sufficiently close to the consummation of the crime to amount to attempt, is a question of degree and depends upon the facts and circumstances of a particular case.

[…]

Sullivan claims that the state failed to produce evidence that he had taken a “substantial step” toward having sexual contact with a minor.

[…]

The state … argues that Sullivan’s acts, when viewed together, constitute a substantial step toward engaging in sexual contact with D.T. However, according to the state’s own account, Sullivan engaged in these acts in preparation for the solicitation itself. For example, at trial the state claimed that Sullivan had written his notes in test format, in order to convince the children that “what he was doing was good” so that they would want to “pass [the] test.” Likewise, the state argued at trial that Sullivan showed the children pictures of naked women “so that they would be in the mood where he could have sexual contact with them once he persuaded them to get their clothes off.” Although these acts may support an inference that Sullivan had a plan to seduce young girls, they amount to no more than preparatory conduct[.] The fact that Sullivan took steps to ensure that his solicitation would be successful does not convert the solicitation into a substantial step.

[…]

Drawing all inferences in favor of the state in the present case, the evidence presented at trial establishes only that Sullivan engaged in preparatory conduct and not that he took a substantial step toward sexual contact with D.T. We therefore reverse Sullivan’s conviction of attempted sexual abuse of a minor in the second degree.

The judgment of conviction for sexual assault in the second degree is VACATED.

Figure 13.2 Various Tests for Attempt Act

Preparatory Crimes

In addition to the criminal offense of attempt, Alaska, similar to other jurisdictions, criminalizes specific preparatory behaviors. For example, Alaska prohibits the mere possession of burglar’s tools. AS 11.46.315. Thus, a defendant could be convicted of a preparatory crime and attempt if the defendant took a substantial step towards the completion of a burglary while in possession of burglary tools.

Example of a Preparatory Crime and Attempt

Hal manufactures a lock pick and takes it to the local coin shop, which is closed. Hal takes the lock pick out and begins to insert it into the coin shop doorknob. A security guard apprehends Hal before he is able to pick the lock. Hal could likely be convicted of possession of burglary tools and attempted burglary because he has committed the essential elements required for both offenses.

Attempt – Culpable Mental State

The culpable mental state required for attempt is having a specific intent to commit the target crime. Generally, reckless or negligent attempts do not exist. Thus, if the prosecution fails to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant acted purposefully with intent to commit the target crime, the defendant will be acquitted of the crime.

Example of a Case Lacking Attempt Intent

Eric is hiking and pauses in front of a sign that states “Only you can prevent forest fires.” Eric reads the sign, pulls out a cigarette, lights it, and throws the lit match into some dry brush near the sign. He starts hiking and when he finishes his cigarette, he tosses the lit cigarette butt into some arid grass. Neither the brush nor the grass burns. Eric probably does not have the requisite criminal intent for attempted criminally negligent burning. Attempt requires intentional conduct. Eric’s conduct is likely criminally negligent because he – as a reasonable person – should have been aware of the risk. On the other hand, if Eric takes the match and tries to ignite a fire, then he has likely committed attempted arson in the third degree. In this example, Eric’s actions demonstrate careless behavior that probably is not sufficient for the crime of attempt.

Defenses to Attempt – Renunciation and Impossibility

Two primary defenses exist for attempt: voluntary renunciation and impossibility.

Voluntary Renunciation (Abandonment)

Renunciation means giving up, refusing, or abandoning one’s criminal objective. Similar to accomplice liability, a defendant who freely and voluntarily renounces their criminal intent can avoid criminal liability for attempt. AS 11.31.100(c). Renunciation is difficult to prove. First, the defendant’s abandonment must be voluntary, complete, and not influenced by an extraneous fact. The defendant must have a change of heart that is not motivated by an increased possibility of detection or a change in circumstances that make the crime’s commission more difficult. In other words, a defendant cannot “renounce” her attempted crime as the police are arresting her, nor simply postpone the crime until a more advantageous time. The abandonment must be complete. See Alaska Criminal Pattern Jury Instructions, 11.31.100(c).

Second, the defendant must prevent the commission of the attempted crime. If the offender has put events in motion that will result in the complete crime, the defendant must successfully terminate the criminal process before the crime is completed. Although difficult to prove, voluntary renunciation gives defendants an incentive to stop progressing towards the consummation of a criminal offense and prevents the crime from occurring without the need for law enforcement intervention. Finally, renunciation is an affirmative defense. The defendant must prove it applies, not the government. Affirmative defenses will be explored shortly.

Example of Voluntary Renunciation

Matthew and Melissa decide they want to poison their neighbor’s dog because it barks loudly and constantly wakes them up every night. The two hatched a plan to rid the world of the pesky dog. Melissa purchases some rat poison at the local hardware store with the idea that Matthew will coat a raw filet mignon with the poison and throw it over the fence. The plan is that the dog will eat the filet, become ill, and die. After Matthew throws the filet over the fence, Melissa changes her mind. She climbs over the fence, picks up the filet, and takes it back to her house for disposal. She also talks Matthew out of poisoning the neighbor’s dog. Melissa has likely voluntarily abandoned the crime and cannot be charged with attempted animal cruelty.

Impossibility as a Defense to Attempt

What if you attempt to commit an impossible crime? For example, what if you try to kill a non-existent person? Is such conduct criminal? It seems unfair to impose criminal liability on an action that would never have been successful and would never have caused actual harm.

Such circumstances raise the issue of impossibility. Two types of impossibility exist: legal impossibility and factual impossibility. Legal impossibility means that the defendant believes what he or she is attempting to do is illegal, when it is in fact not. Conversely, factual impossibility means that the defendant could not complete the target crime because an extraneous factor prevented the criminal act. Some jurisdictions allow legal impossibility as a defense, but none allow factual impossibility.

Alaska makes no such distinction; neither legal impossibility, nor factual impossibility, is a defense against an attempt crime. AS 11.31.100(b). The reason is simple – it is difficult to tell the difference and under both scenarios the offender has committed a voluntary act and concomitantly a criminal culpable mental state. The basic elements of a criminal offense have been met.

Example of Legal Impossibility

Matthew and Melissa are still planning to kill the neighbor’s dog. Assume that Melissa is eighteen. Melissa believes that an individual must be twenty-one to purchase rat poison because that is the law in Montana (where she lived five years ago). In actuality, Alaska allows anyone over the age of eighteen to buy rat poison. When she tries to pay for the rat poison, the store asks for identification. Melissa believes she’s committing a crime, makes an excuse, and leaves. Melissa regains her composure and goes to a second store. The second store does not ask for identification, and Melissa successfully purchases rat poison. Since Alaska does not recognize the defense of legal impossibility, Melissa’s mistaken belief that she has committed a crime transforms her legal act into an illegal one.

Example of Factual Impossibility

Now let’s change the hypothetical. Assume Matthew throws a coated filet over the fence with the intent to poison the dog. Unbeknownst to Melissa and Matthew, the dog is on an overnight camping trip with its owners. Both Melissa and Matthew are under the mistaken belief that the dog is present and will eat the filet. This mistake of fact will not excuse Melissa and Matthew’s attempted animal cruelty. Melissa and Matthew intentionally engaged in conduct that would result in the poisoning of the dog if the facts were as Melissa and Matthew believed them to be. Thus, Melissa and Matthew have likely committed attempted animal cruelty regardless of the fact that their plan could not succeed under the circumstances. Factual impossibility is not a defense under Alaska law.

Merger Doctrine

The crime of attempt merges into the completed crime. AS 11.31.140(c). Double jeopardy precludes a defendant from being punished for attempt and the completed crime. See Starkweather v. State, 244 P.3d 522, 530 (Alaska App. 2010). If a defendant is charged and convicted of both an attempt crime and the target crime, the attempt merges into the completed crime at sentencing. This rule makes sense given that every complete crime necessarily includes an attempt to commit the crime. It would be unfair to punish an offender for both a completed crime and the attempted crime.

Example of Merger

Let’s assume that Melissa and Matthew were successful. The neighbor’s dog eats the poisoned filet and dies. Melissa and Matthew may not be punished for both attempted animal cruelty and animal cruelty. Once the crime is complete, the attempt crime merges into the consummated offense, and Melissa and Matthew may only be punished for the completed animal cruelty.

Attempt Grading

Most jurisdictions, including Alaska, classify an attempt as a lower-level offense than the completed offense. Generally speaking, the crime of attempt is classified one level below the completed crime. AS 11.31.100(d). For example, killing your neighbor’s noisy dog constitutes animal cruelty, a class C felony. AS 11.61.140(a)(3). If a person attempts to commit animal cruelty, the person is guilty of a class A misdemeanor, a lower-level offense with a lower penalty provision. This lower classification frequently reduces the potential punishment.

There is one notable exception to this rule – attempted murder. Attempted murder remains an unclassified felony, just like the completed offense: first-degree murder. Both crimes provide for the same maximum punishment – 99 years imprisonment. Although both are unclassified offenses, case law requires the sentencing court to recognize that attempted murder is not as serious as a completed murder, and the ultimate sentence should reflect this difference. See e.g., Rudden v. State, 881 P.3d 328 (Alaska App. 1994).