Burglary and Trespass

Although we often associate burglary with theft, it is actually an enhanced form of trespass. At common law, burglary was the “breaking and entering of another’s dwelling at night with the intent to commit a felony therein.” See Burglary Black’s Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019). This narrow definition was an effort to protect citizens in their property, and specifically, in their homes. A “man’s home [was] his castle,” and burglary specifically criminalized the invasion of habitation. Because burglary required the defendant to intentionally commit a felony once inside, burglary was viewed as a series of steps towards the commission of the target offense (generally theft), but since it was a crime against habitation and frequently instilled fear in the victims, it was severely punished. In this regard, burglary was truly a unique form of attempt. See generally, Wayne R. LaFave, Substantive Criminal Law, §21.1(g) (3d. ed. 2018).

Although Alaska has significantly revised the crime of burglary since its territorial days, its primary purpose remains: to punish the “breaking into someone’s property [that] is likely to instill terror in the occupants of the property.” See Pushruk v. State, 780 P.2d 1044, 1046 (Alaska App. 1989). Burglary remains a quasi-inchoate crime akin to attempt; the defendant is punished for entering a building with the intent to commit a crime therein. Completion of the target crime is unnecessary. See State v. Ison, 744 P.3d 416 (Alaska App. 1987).

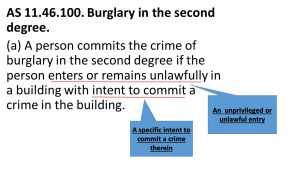

All burglary offenses, regardless of jurisdiction, contain two basic principles – (1) an unprivileged or unlawful entry into a structure, with (2) a specific intent to commit a crime therein. See generally Taylor v. United States, 495 U.S. 575 (1990) (recognizing that the generic, contemporary meaning of burglary “contains at least the following elements: an unlawful or unprivileged entry into or remaining in a building or other structure with intent to commit a crime.”).

Modern burglary statutes tend to grade the offense based on the type of structure entered and the seriousness of the surrounding circumstances. Alaska has followed this trend. The general burglary statute (second-degree burglary) provides the basic burglary definition. AS 11.46.310. Second-degree burglary has a maximum punishment of five years. Second-degree burglary is relatively straightforward. See Figure 11.2.

Figure 7.2 Alaska Criminal Code – Burglary

First-degree burglary is an aggravated burglary and occurs when (1) the defendant was armed with a weapon, (2) the structure burglarized was a dwelling, or (3) the defendant injured an occupant while inside. AS 11.46.300. First-degree burglary is elevated because of the existence of one of the attendant circumstances identified above. First-degree burglary is punishable by up to 10 years of imprisonment. Also, recall that first-degree burglary is an inherently dangerous felony for felony-murder (provided however, the target crime is not murder). AS 11.41.110(a)(2); 11.41.115(c).

Unauthorized Entry

The actus reus of burglary is satisfied upon a “breaking and entering.” The crime is complete upon the entry. An entry does not necessarily mean the intruder must place their entire body inside a building. Instead, an entry occurs when “an intruder enters by entry of his whole body, part of his body, or by insertion of any instrument that is intended to be used in the commission of a crime.” See Sears v. State, 713 P.2d 1218, 1220 (Alaska App. 1986). The converse is also true. A person who is unable to penetrate a building is only guilty of attempted burglary. See State v. Ison, 744 P.2d 416 (Alaska App. 1987).

Example of an Unauthorized Entry

Jed uses a burglar tool to remove the window screen of a residence. The window is open, so once Jed removes the screen, he places both hands on the sill, and begins to launch himself upward. The occupant of the residence, who was watching Jed from inside, slams the window down on Jed’s hands. Jed has likely committed the unlawful entry required for burglary. When Jed removed the window screen, he committed a breaking. When Jed placed his hands on the windowsill, his fingers intruded into the residence, which satisfied the entry requirement. Jed will likely be prosecuted for burglary rather than attempted burglary, even though he never managed to gain access to the residence.

Example of No Entry

Let’s change the hypothetical above slightly. Instead of using a burglary tool to remove a window screen, let’s assume Jed approaches the front door of the residence to gain entry. Jed inserts a credit card into the door jam, between the door and its frame, intending to slip the lock (and thereby unlocking the door). The credit card never protrudes into the residence. The occupant of the residence, who was watching Jed from inside, runs up to the front door and activates the deadbolt lock. In this scenario, Jed did not penetrate the building – either with his body or an instrument. Jed is guilty of attempted burglary, not a completed burglary. See e.g., State v. Ison, 744 P.2d 416 (Alaska App. 1987).

“Enter or Remain Unlawfully” Under Alaska Law

Although the voluntary act necessary for burglary has not changed, the common law term of “breaking and entering” has been replaced by the broader concept of “enter or remain unlawfully.” AS 11.46.310. “Enter or remain unlawfully” is defined to mean not only entering a place where the defendant is not permitted, but also includes staying inside somewhere after the premises has closed. Thus, if a person hides inside a department store until it closes with the intent to commit a theft, the person is guilty of burglary.

Conversely, if a person lawfully enters a store – for example, through the front door, during regular business hours and commits a crime– the person is only criminally liable for the crimes they commit thereafter. Put another way, if a defendant commits a theft while inside a store, the defendant is not guilty of burglary, even if the theft occurs in a restricted area. The initial entry was not unlawful. See Arabie v. State, 699 P.2d 890 (Alaska 1985).

You be the Judge…

Dan entered a grocery and liquor store in Fairbanks while it was open for business. The store was a single building with a single main entrance into a foyer. The foyer contained separate entrances to the liquor and grocery departments. The back of the store contained an employee work and storage area, which employees could access from either department. Dan entered a beer cooler and back storage room that was posted “employees only.” While in the back room, Dan picked up two cases of beer and attempted to run out the back door. A store employee heard Dan and stopped him from leaving. The prosecutor has charged Dan with one count of second-degree burglary for “entering or remaining unlawfully” in a building with the intent to commit a crime therein (i.e., theft). Is Dan correctly charged with second-degree burglary? Check your answer at the end of the chapter.

A Specific Intent to Commit a Crime Therein

Burglary is a dual intent crime. A defendant must knowingly enter or remain unlawfully inside a building with the intent to commit the target crime. The government must prove that the defendant (1) knew he was trespassing when he entered or remained in the building and (2) at the time of the trespass, he intends to commit an additional crime inside.

Alaska has departed however from the common law doctrine that a defendant must have a specific intent to commit a crime at the time he “breaks and enters.” If a defendant has the intent to commit a crime at the time his privilege to be on the premises is terminated, the person is guilty of burglary. Thus, a defendant commits the crime of burglary at the time the defendant’s presence becomes unlawful and the defendant has an intent to commit a crime. Recall that if a person hides inside a department store until it closes in an effort to steal merchandise, the person is guilty of burglary.

Building versus Dwelling

Alaska grades burglary differently based on the type of property entered. If a defendant burglarizes a “building,” the defendant is guilty of simple burglary (second-degree burglary); if a defendant burglarizes a dwelling, the defendant is guilty of an aggravated burglary (first-degree burglary). Building is defined broadly to include not only what we ordinarily think of as a building, but also any “propelled vehicle” or any structure large enough for a human to physically enter and occupy. AS 11.81.900(b)(5).

A dwelling is any building that “is designed for use or is used as a person’s permanent or temporary home or place of lodging.” AS 11.81.900(b)(22). Since a camper is a building for use as a person’s temporary home, it would be a dwelling for purposes of the burglary statute. Dwelling also includes tents, hotel rooms, and even fishing boats (if equipped for that purpose). See Shoemaker v. State, 716 P.2d 391 (Alaska App. 1986) (recognizing that a fishing boat was a “dwelling” if equipped to house fishers). Thus, entering a person’s tent who is living on the street, with the intent to steal their belongings once inside, is an aggravated burglary in Alaska.

Coleman v. State, 407 P.3d 502 (Alaska App. 2017)[1]

At first blush, one might assume that classifying a structure as either a building or dwelling is relatively easy. Unfortunately, such an assumption would be wrong. Generally, whether a structure is a building or dwelling is a question of fact for the jury. See State v. Austin, 883 P.3d 992 (Alaska App. 1994). However, if a defendant breaks into a structure that is neither a building, nor a dwelling, the defendant cannot be charged with burglary. Such was the issue in the following case. In Coleman v. State, the question before the Court of Appeals was whether a bicycle shed constituted a “building” for purposes of the burglary statute. Such a distinction is significant – depending on the definition of building, Coleman is either guilty of two misdemeanors (trespass and theft) or a felony and a misdemeanor (burglary and theft).

407 P.3d 502

Court of Appeals of Alaska.

James Kevin COLEMAN (aka James Kevin Almudarris), Appellant,

v.

STATE of Alaska, Appellee.

October 13, 2017

OPINION

Judge ALLARD.

James Kevin Coleman was convicted, following a jury trial, of second-degree burglary [and other offenses] based on allegations that he broke into a storage shed used by a commercial bike shop and stole two bicycles. …

On appeal, Coleman challenges his conviction for burglary, arguing that the bicycle storage shed was too small to qualify as a “building” for purposes of the burglary statutes.

…

For the reasons explained in this opinion, we conclude that the bicycle storage shed qualified as a “building” as that term is defined in the burglary statutes.

…

Accordingly, we affirm Coleman’s convictions for second-degree burglary[.]

Why we conclude that the bicycle storage shed was large enough to qualify as a “building” for purposes of Alaska’s burglary statute

Under AS 11.46.310(a), a person commits burglary if the person “enters or remains unlawfully in a building with the intent to commit a crime in the building.” Alaska Statute 11.81.900(b)(5) defines “building,” in pertinent part, as follows:

“building,” in addition to its usual meaning, includes any propelled vehicle or structure adapted for overnight accommodation of persons or for carrying on business[.]

In the current case, Coleman was convicted of second-degree burglary for breaking into a shed that was used to store bicycles for a business. The shed was a permanent wooden structure with four walls, a floor, and a roof; it contained multiple enclosed storage lockers, secured by individual padlocks. Although the record does not reveal the exact dimensions of the shed, the evidence presented at trial indicated that the shed was approximately chest- to shoulder-high, and the shed could contain 20 to 25 bicycles. To enter the shed to retrieve the bicycles, an average-sized person would need to stoop.

At trial, the general manager of the bicycle shop testified that the shed was used to store bicycles that were brought in for repairs. On an average summer work day, 5 to 6 employees would access the shed to retrieve or store bicycles. The manager testified that employees would typically not need to fully enter the shed to retrieve the bicycles, but that they would sometimes have to crawl all the way into the shed if they were having difficulty getting a bicycle out. The entrance to each storage locker in the shed was kept secured with a padlock and equipped with a break-in alarm.

On appeal, Coleman argues that the shed did not qualify as a “building” for purposes of the burglary statute. Coleman contends that, because the crime of burglary was originally intended to protect dwellings, a structure can only qualify as a “building” for purposes of the burglary statute if it is either designed for human habitation or large enough to “comfortably accommodate people moving around” in it. According to Coleman, because the shed was made to accommodate bicycles and not people, and because an average-sized person would need to stoop to enter the shed, the shed did not qualify as a “building,” and his conviction for second-degree burglary must be reversed.

In response, the State argues that the bicycle storage shed was a building both in the “usual meaning” of the word and because the shed was a structure that had been “adapted” for carrying on the bicycle shop’s business—specifically, the storing and repairing of bicycles. The State concedes, however, that “at some point, a storage unit [may be] so small that it could not reasonably be considered ‘a structure,’ ” and as such, would not be “a building.”

The issue presented here is, therefore, how large a structure must be in order to be considered a “building” for purposes of the burglary statute. Because the statute is ambiguous on this point, we look to the purpose of the legislation and the legislative history for indications of legislative intent.

The definition of “building” codified in AS 11.81.900(b)(5) is derived from Oregon law. Both Alaska and Oregon define “building” broadly, and the two statutory definitions of “building” are essentially the same. As already set out, the Alaska statute defines “building” to include “its usual meaning” as well as “any propelled vehicle or structure adapted for overnight accommodation of persons or for carrying on business.” Likewise, under the Oregon statute, “building” is defined “in addition to its ordinary meaning” as also including “any booth, vehicle, boat, aircraft or other structure adapted for overnight accommodation of persons or for carrying on business therein.”

The legislative history of these statutory definitions indicates that the Alaska and the Oregon legislatures intended these definitions to be expansive. The commentary to the tentative draft of Alaska’s 1978 criminal code revision states that the definition is intended to be “broad enough to include house trailers, mobile field offices, house boats, vessels and even tents used as dwellings.” The commentary to the Oregon Criminal Code likewise explains that the definition of “building” was expanded from the “ordinary meaning of the word” so as to also include “those structures and vehicles which typically contain human beings for extended periods of time, in accordance with the original and basic rationale of the crime [of burglary]: protection against invasion of premises likely to terrorize occupants.”

Coleman relies heavily on the Oregon commentary for his claim that the Oregon and Alaska legislatures intended to limit the definition of “building” to only those vehicles or structures that “typically contain human beings for extended periods of time.” But neither the plain language of the statute nor the legislative history support this claim.

At common law, the crime of burglary required proof that the defendant unlawfully entered a human habitation. Burglary was defined as the breaking and entering of a dwelling at night with the intent to commit a crime therein. The common-law offense of burglary was therefore strictly an offense aimed at protecting the security of habitation rather than property.

But statutory enactments over the past 60 years have changed and expanded the common-law definition of the offense. For most jurisdictions, the requirement that the crime take place at night or that it be directed at a dwelling have disappeared. Instead, most states (including Alaska and Oregon) now define burglary simply as unlawfully entering or remaining in a “building” with the intent to commit a crime therein. The offense is elevated to a higher degree of burglary with increased punishment if the “building” is a “dwelling” or if the defendant’s conduct poses a particular danger to people found within the building.

This transformation is evident in the relevant Oregon caselaw, which has upheld burglary convictions involving storage sheds and storage containers, even though they were designed to accommodate property, not people. For example, in State v. Essig, the Oregon Court of Appeals held that a large potato storage shed qualified as a building under the burglary statute, describing it as a substantial structure and thus a building within the ordinary meaning of the term. Similarly, in State v. Handley, the Oregon Court of Appeals held that a storage locker in an apartment complex’s carport qualified as a building. In State v. Barker, the court held that “self-contained storage units” within a commercial storage facility qualified as “buildings,” and in State v. Webb, the court held that a tractor trailer adapted by a business to store goods likewise qualified as a “building.”

Coleman points out that these Oregon cases all involve storage containers or sheds that are considerably larger than the bicycle storage shed involved in his case. For example, the potato shed in Essig was large enough to “contain several trucks.” Likewise, the tractor trailer in Webb was twenty-five feet long and eight to nine feet wide (although no height was listed). But not all of the Oregon cases involve such large storage structures. The storage lockers in Handley were only four feet wide, nine feet long, and seven feet high. And the dimensions of the storage unit in Barker were essentially unknown, although the court noted that it was “large enough for a human being to enter and move about.”

[…]

Like the storage units in Barker, the storage shed at issue in Coleman’s case appears to fit within the dictionary meaning of the term “building.” Black’s Law Dictionary defines the word “building” as:

[A] structure designed for habitation, shelter, storage, trade, manufacture, religion, business, education, and the like. A structure or edifice inclosing a space within its walls, and usually, but not necessarily, covered with a roof.

Here, the storage shed was a permanent structure with four walls, a roof, a floor, and a fixed entry place through which a person could enter the structure in order to store or retrieve the bicycles placed there by the business.

Coleman contends that, despite these attributes, the storage shed does not qualify as a “building” because the entrance was not high enough for an average-sized person to enter without stooping and it was not big enough for an average-sized person to move around “comfortably.”

We agree with Coleman that, as a general matter, a structure that is too small for a human being to physically enter and occupy with their whole body cannot be considered a “building” that can be burglarized. We note that courts in other jurisdictions have reached a similar conclusion with regard to their burglary statutes.

For example, in Paugh v. State, the Wyoming Supreme Court held that a three-foot display case in a department store was not a “separately secured or occupied portion” of a building for purposes of Wyoming’s burglary statute because the display case was “too small to accommodate a human being.” The Washington Court of Appeals similarly held that a police evidence locker that was 10 inches high, 10 inches wide, and 2 feet deep was too small to qualify as a “building” under Washington’s burglary statute. Coin boxes at a car wash have likewise been found to be too small to qualify as a “building,” as have soft drink vending machines, and a large tool box on wheels.

But these cases all involve containers that are significantly smaller than the storage shed at issue in Coleman’s case. Here, the trial testimony indicated that the bicycle shop’s storage shed was designed to be wide enough, long enough, and tall enough—approximately chest- to shoulder-high—to allow an average-sized person to enter the shed and move about, albeit not necessarily for an extended period of time and not necessarily entirely comfortably. Indeed, the testimony at trial established that human beings did, at times, fully enter the shed to retrieve the bicycles stored inside.

Given these circumstances, and given that the shed otherwise exhibited all of the attributes associated with the term “building” in the usual meaning of the term, we conclude that the storage shed at issue here qualified as a “building” for purposes of Alaska’s second-degree burglary statute. We therefore reject Coleman’s claim that the evidence was insufficient to support his conviction for second-degree burglary on this ground.

[…]

Conclusion

… We … AFFIRM the judgment of the superior court.

Criminal Trespass

Criminal trespass is a related, but distant cousin of burglary. Criminal trespass criminalizes the unlawful intrusion onto someone else’s real property. Like burglary, criminal trespass is graded based on perceived severity.

Criminal Trespass in the Second Degree occurs when a person “enters or remains unlawfully” in or upon a premises. AS 11.46.330(a)(1). Premises means any real property and any building. A simple trespass onto land or in a building will be second-degree criminal trespass. Criminal Trespass in the Second Degree also occurs when a person enters or remains unlawfully in a propelled vehicle. AS 11.46.330(a)(2). This second theory of trespass covers relatively trivial conduct, such as unlawfully entering a vehicle to take a nap. (If a person unlawfully takes a propelled vehicle, the person is not guilty of trespass, but the more serious offense of Vehicle Theft).

Criminal Trespass in the First Degree covers two forms of more serious conduct. AS 11.46.320. The first is entering or remaining upon real property with the intent to commit a crime on the property. For example, if a person enters private land with the intent to take an animal out of season, the person would be guilty of first-degree criminal trespass. Ordinarily, trespass on land would be prosecuted as second-degree criminal trespass, but if the defendant intends to commit a crime on the land, then the trespass is elevated to aggravated criminal trespass (first-degree trespass).

First-degree criminal trespass also occurs when a person enters or remains unlawfully in a dwelling. AS 11.46.330(a)(2). Take note that this conduct would be first-degree burglary if the person entered or remained unlawfully in the dwelling with the intent to commit a crime. But if the person has no intention of committing a crime inside the dwelling, the person is only guilty of aggravated trespass.

For purposes of trespass, “enter or remain unlawfully” means failing to leave the premises after being lawfully directed to do so. AS 11.46.350(a)(2). Thus, a person “remains unlawfully” if the person fails to leave after being informed that they are no longer welcome. Property owners (or their designees) can notify individuals that they are not privileged to enter either through signage (i.e., a “closed” sign) or personal notification (i.e., “you are trespassed”). For unimproved or unfenced land, landowners must post signage in a reasonably conspicuous manner. AS 11.46.350(b). However, if a person enters land with the intent to commit a crime thereon (for example, to commit theft of property on the land), the law does not require that the land be posted. AS 11.46.350(b)(2).

Emergency Use of Premises

The law provides a limited affirmative defense to burglary and criminal trespass. If the unlawful entry was due to an emergency “of immediate and dire need” the person is not guilty. AS 11.46.340. To take advantage of the defense, the defendant must notify local law enforcement or the owner of the unlawful entry once able and within a reasonable amount of time. For example, a person being chased by a bear may break into a cabin to avoid being attacked. But once the bear has left the area, the person must notify the homeowner or local law enforcement of their unlawful entry. Otherwise, the person is guilty of trespass; they are not entitled to claim the affirmative defense. As an affirmative defense, the defendant bears (pun intended) the burden of proving the emergency by a preponderance of the evidence.

- Coleman v. State, 407 P.3d 502 (Alaska App. 2017) was abrogated on different grounds in Phornsavanh v. State, 481 P.3d 1145 (Alaska App. 2021)). ↵