Causation and Harm

The last two elements are causation and harm. Simply put, the defendant must cause the requisite harm. If the defendant’s actions did not cause the resulting harm, criminal liability will likely not attach. Causation can be a nebulas concept – at its core, everything is causally related. But the law places boundaries around criminal liability. Even though a defendant may initiate a series of events that ultimately results in a particular harm, it may be unjust to hold the defendant criminally responsible. The law surrounding causation has evolved to promote fairness. In this section, we will explore factual cause and legal cause, as well as situations where the defendant may be insulated from criminal responsibility. Let’s revisit first-degree murder to see these elements in statute.

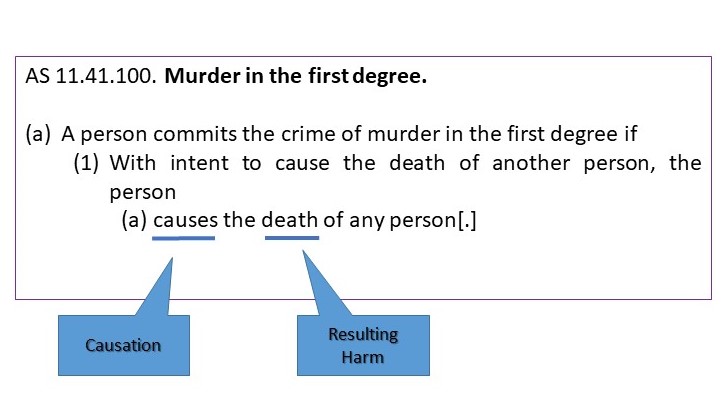

Figure 4.7 Alaska Criminal Code – Murder in the First Degree

Factual Cause

Every causation analysis is twofold. First, the defendant must be the actual cause, or the cause-in-fact, of the victim’s harm. This is routinely referred to as the “but for” test. Put another way, “but for the defendant’s act, the harm would not have occurred.” This is a relatively easy analysis – the defendant is the factual cause of the victim’s harm if the defendant’s actions started the chain of events that led to the eventual harm.

Example of Factual Cause

Henry and Mary get into an argument over their child custody agreement. Henry gives Mary a hard shove. Mary staggers backward, is struck by lightning, and dies instantly. In this example, Henry’s act (i.e. the shove) forced Mary to fall into the area where the lighting happened to strike. Henry is the cause-in-fact of Mary’s death. But for Henry shoving Mary, Mary would have lived. The more difficult question is whether it is just to punish Henry for Mary’s death. Should Henry be punished when no reasonable person could have imagined that lighting would strike Mary at the moment Henry shoved her?

Legal Cause (Proximate Cause)

The second part of the causation analysis ensures the fair application of criminal liability. In addition to being the cause-in-fact of the victim’s harm, the defendant must also be the legal or proximate cause of the harm. Proximate cause means that the defendant’s conduct must be closely related to the harm it engenders. The defendant’s conduct need not be the sole factor producing the victim’s injury. Rather, the defendant’s conduct must have been a “substantial factor” in bringing about the result. As the Model Penal Code states, the actual result cannot be “too remote or accidental in its occurrence to have a [just] bearing on the actor’s liability”. (Model Penal Code § 2.03 (2)(b)).

The test for proximate cause is reasonable foreseeability. See e.g., Johnson v. State, 224 P.3d 105, 111 (Alaska 2010). A defendant is responsible for the natural consequences of their acts or their failure to act. Natural consequences are those consequences that are reasonably foreseeable in light of ordinary experience. The trier of fact must be convinced that when the defendant acted, a reasonable person could have foreseen or predicted that the end result would occur. For this reason, Henry from the previous example is not the legal cause of Mary’s death. A reasonable person would not have foreseen that lighting would strike Mary immediately after the shove. This is not a natural consequence in light of ordinary experience.

Example of Legal Cause

Imagine that Henry and Mary get into the same argument over their child custody agreement, but this time they are in their garage, which is crowded with furniture. Henry gives Mary a hard shove, even though she is standing directly in front of a large entertainment center filled with books and a large sixty-inch television set. Mary staggers backward into the entertainment center and it crashes down on top of her, killing her. In this situation, Henry is the factual cause of Mary’s death since he started the chain of events that led to her death with his push. In addition, it is reasonably foreseeable that Mary might suffer a serious injury or death when shoved directly into a large and heavy piece of furniture. In this example, Henry is likely the factual and legal cause of Mary’s death. Proximate cause is ordinarily an issue for the jury.

Intervening or Superseding Cause

A related situation is the application of intervening or superseding causes. What happens when someone or something interrupts or exacerbates the chain of events started by the defendant? The law analyzes this situation through the lens of intervening or superseding causes. Typically, an intervening or superseding cause cuts off the defendant’s criminal liability. Harm that is linked to the defendant’s conduct, but is primarily caused by abnormal, unforeseeable conduct by the victim or third person, severs the casual chain.

Example of an Intervening Superseding Cause

Let’s revisit Henry and Mary. Let’s assume that Henry pulls out a knife and chases Mary out of the garage (instead of shoving her). Mary escapes and hides in an abandoned shed. Half an hour later, Wes, a homeless man living in the shed, returns from a day of panhandling. When he discovers Mary in the shed, he kills her and steals her jewelry. Although Henry is still the factual cause of Mary’s death, (i.e., but for Henry chasing Mary into the shed, Wes would not have found her), Henry is not likely the legal cause of Mary’s death. Instead, Wes is probably an intervening cause of Henry’s criminal liability – Wes interrupted the chain of events started by Henry. Thus, Wes, not Henry, will likely be prosecuted for Mary’s death (although Henry may be prosecuted only for assault with a deadly weapon).

Kusmider v. State, 688 P.2d 957 (Alaska App. 1984).

In the above example, Wes interrupted the chain of events, thereby relieving Henry of criminal liability. The following case, Kusmider v. State, addresses the situation of when a third person exacerbates the resulting harm. As you read Kusmider, ask yourself whether it is fair to hold Kusmider accountable for murder in this situation.

688 P.2d 957

Court of Appeals of Alaska.

Thomas KUSMIDER, Appellant,

v.

STATE of Alaska, Appellee.

No. 7845.

Sept. 21, 1984.

OPINION

BRYNER, Chief Judge.

Thomas Kusmider was convicted, after a jury trial, of murder in the second degree. He appeals, contending that Superior Court Judge Karl S. Johnstone erred in excluding evidence relating to the proximate cause of the victim’s death. We affirm.

On November 15, 1982, Kusmider’s girlfriend told Kusmider that an acquaintance, Arthur Villella, had sexually assaulted her. Kusmider went to Villella’s home in Anchorage. A confrontation ensued, and Kusmider shot Villella. The bullet entered Villella’s neck above the Adam’s apple. Although the wound did not sever any major arteries, it damaged smaller vessels, causing blood to drain down Villella’s windpipe.

Villella was unconscious by the time an ambulance arrived. He was attended by paramedics, who inserted a tube in his windpipe to help his breathing. En route to the hospital, however, Villella began flailing his arms and pulled the tube from his throat. Villella died approximately one hour after arriving at the hospital.

At Kusmider’s trial, a pathologist testified that Villella’s death was caused by the gunshot wound to his throat. However, the pathologist stated that the wound, while life-threatening, might have been survivable. Kusmider then asked the court for permission to present evidence on the issue of proximate cause. He argued that, if allowed to pursue the issue, he might be able to establish that Villella would have survived the gunshot wound if he had not been able to pull the tube from his windpipe. Kusmider maintained that the paramedics who transported Villella might have been negligent in failing to restrain Villella’s arms. Kusmider insisted that he was entitled to have the jury consider whether possible negligence by the paramedics constituted an intervening or superseding cause of Villella’s death, rendering the gunshot wound too remote to be considered the proximate cause of death.

Judge Johnstone precluded Kusmider from pursuing the issue of proximate cause before the jury. The judge ruled that negligent failure to provide appropriate medical assistance could not, under the circumstances, interrupt the chain of proximate causation and that, therefore, no jury issue of proximate cause had been raised by Kusmider’s offer of proof.

On appeal, Kusmider renews his argument, contending that the jury should have been permitted to hear evidence on the issue of proximate cause. We believe that Kusmider’s argument is flawed. Kusmider is correct in asserting that proximate cause is ordinarily an issue for the jury. Of course, in every criminal case the state must establish and the jury must find that the defendant’s conduct was the actual cause, or cause-in-fact, of the crime charged in the indictment. Here, testimony that Villella actually died from the gunshot wound was undisputed, and the actual cause of death was not in issue. On appeal, Kusmider does not argue that the trial court’s exclusion of evidence relating to proximate cause infringed in any way on the jury’s ability to determine actual cause.

Case law and commentators agree that, when death is occasioned by negligent medical treatment of an assault victim, the original assailant ordinarily remains criminally liable for the death, even if it can be shown that the injuries inflicted in the assault were survivable; under such circumstances, proximate cause is not interrupted unless the medical treatment given to the injured person was grossly negligent and unforeseeable.

In the present case, Kusmider offered to prove only that the paramedics who treated Villella might have been negligent in failing to restrain Villella’s arms. Kusmider did not argue that he could demonstrate gross negligence or recklessness, nor did he contend that the circumstances surrounding Villella’s death were unforeseeable. Since, as a matter of law, only grossly negligent and unforeseeable mistreatment would have constituted an intervening cause of death and interrupted the chain of proximate causation, we conclude that Judge Johnstone did not err in excluding evidence relating solely to the issue of negligence by the paramedics who treated Villella.

Even assuming Kusmider had offered to prove that the conduct of the paramedics was both unforeseeable and grossly negligent, we would still conclude that the trial court correctly excluded the evidence relating to proximate cause. In cases involving death from injuries inflicted in an assault, courts have uniformly held that the person who inflicted the injury will be liable for the death despite the failure of third persons to save the victim. One commentator notes:

“The question is not what would have happened, but what did happen,” and there can be no break in the legally-recognized chain of causation by reason of a possibility of intervention which did not take place, because a “negative act” is never superseding. Moreover, an injury is the proximate cause of resulting death although the deceased would have recovered had he been treated by the most approved surgical methods, or by more skillful methods, or “with more prudent care,” or “with a different diet and better nursing,” or “with proper caution and attention.” The same is true even if the injured person did not take proper care of himself, or neglected to obtain medical treatment, or delayed too long in doing so, or refused to submit to a surgical operation despite medical advice as to its necessity.

R. Perkins & R. Boyce, Criminal Law § 9 at 799–800 (footnotes omitted).

Here, Kusmider did not claim that the conduct of the paramedics inflicted any new injuries on Villella nor did he even assert that the paramedics aggravated the injuries inflicted by the gunshot wound. Rather, the gist of his claim was that negligence in failing to restrain Villella’s arms enabled Villella to disrupt the apparently successful emergency treatment that he had begun to receive. Thus, in support of his argument that proximate cause had been interrupted, Kusmider attempted to rely exclusively on the proof of a negative act: that the paramedics negligently failed to take adequate precautions to restrain Villella. Since Kusmider never offered to prove that the paramedics engaged in any affirmative conduct that might have aggravated Villella’s injuries and hastened his death, he could not, as a matter of law, have established a break in the chain of proximate cause, even if he could have shown that the paramedics committed gross and unforeseeable negligence by their failure to act. In short, no matter how negligent the paramedics may have been in failing to prevent Villella’s death, it is manifest that the gunshot fired by Kusmider remained a substantial factor—if not the only substantial factor—in causing Villella’s death. No more is required for purposes of establishing proximate cause.

Because the evidence proffered by Kusmider could not, as a matter of law, have established a break in the chain of proximate causation, we hold that Judge Johnstone did not err in excluding this evidence from trial.

The judgment of conviction is AFFIRMED.

Exercises

Answer the following question. Check your answer using the answer key at the end of the chapter.

- Phillipa sees Fred picking up trash along the highway and decides she wants to frighten him. She drives a quarter of a mile ahead of Fred and parks her car. She then hides in the bushes and waits for Fred to show up. When Fred gets close enough, she jumps out of the bushes screaming. Frightened, Fred drops his trash bag and runs into the middle of the highway where he is struck by a vehicle and killed. Is Phillipa’s act the legal cause of Fred’s death? Why or why not?