Criminal Act

The majority of the time, the criminal act, or actus reus, is defined as a voluntary and conscious bodily movement. Remember, the criminal law generally punishes prohibited acts. In some circumstances however, the criminal act is defined as an omission to act. When the law criminalizes a person’s failure to act, the law requires the person to be informed of their duty.

The Requirement of Voluntariness

The criminal act must be performed voluntarily. Involuntary acts cannot form the basis of criminal liability. Alaska law describes a voluntary act as “[a] bodily movement performed consciously as a result of effort and determination.” AS 11.81.900(b)(66). In other words, the defendant must consciously control the action. Involuntary acts such as reflexes, convulsions, bodily movements during unconsciousness or sleep, or movements during hypnosis are excluded. See generally Model Penal Code § 2.01 (2). Involuntary acts, for purposes of the actus reus, do not include compelled or coerced acts. Such “involuntary acts” may excuse a person’s criminal behavior, but are “voluntary” for purposes of the criminal act.

Example of an Involuntary Act

Perry is hypnotized at the local county fair. The hypnotist directs Perry to smash a banana cream pie into his girlfriend Shelley’s face. Smashing a pie into a person’s face without their consent is likely misdemeanor assault. However, since Perry did not commit the act voluntarily he should not be convicted of a crime. Punishing Perry for assault serves little societal interest given he was not in control of his behavior. No punishment would change Perry’s, or others, behavior in the future.

Purpose of the Criminal Act

Voluntariness serves an important penological purpose. The belief that criminals must be able to avoid criminal punishment is a central purpose of the criminal justice system. Criminalizing involuntary actions fails to achieve this purpose. However, only one voluntary act is enough to fulfill the actus reus. If a voluntary act is followed by an involuntary one, the law will impose criminal liability.

Example of a Voluntary Act followed by an Involuntary Act

Timothy attends a party at a friend’s house and consumes several glasses of red wine. Timothy then drives home. While driving, Timothy passes out at the wheel and hits another vehicle, killing the other driver. Timothy is likely guilty of manslaughter. Timothy’s acts of drinking several glasses of wine and then driving were voluntary. Even though Timothy caused the collision while unconscious (an involuntary act), his involuntary act was preceded by conscious, controllable, and voluntary action.

Wagner v. State, 390 P.3d 1179 (Alaska App. 2017)

As you will see, recognizing the difference between a voluntary act and one’s culpable mental state can be difficult. The following case explores the situation when a person may not know that their voluntary action will lead to an involuntary action. As you read Wagner, ask yourself whether it is fair to hold Wagner responsible in such a situation. Does the Court’s ruling achieve the penological purpose discussed above?

390 P.3d 1179

Court of Appeals of Alaska.

Richard Laverne WAGNER Jr., Appellant,

v.

STATE of Alaska, Appellee.

Court of Appeals No. A-11682

January 27, 2017

OPINION

Judge MANNHEIMER.

In the early morning of August 23, 2011, Richard Laverne Wagner Jr. came to the end of a street, failed to stop, and drove his van into a tree. When the police arrived, Wagner told the officers that he had recently dropped off some out-of-town relatives at their hotel, and that he had then taken some medications and started driving home. Wagner told the officers that, when he came to the end of the street, he attempted to apply his brakes, but he mistakenly pressed the accelerator instead.

Later, however, Wagner changed his story: he told the police that all he remembered was being in his home, and then the next thing he remembered was striking the tree.

Because Wagner admitted drinking and smoking marijuana, he was arrested for driving under the influence. His breath test showed a blood alcohol concentration of .066 percent—below the legal limit. Wagner then consented to a blood test. A subsequent chemical analysis of Wagner’s blood showed that he had consumed zolpidem—a sedative that was originally sold under the brand name Ambien, and is now available under several brand names.

Wagner was charged with driving under the influence and driving while his license was revoked.

At Wagner’s trial, his defense attorney elicited testimony (from the State’s expert witness) that one of the potential side effects of zolpidem is “sleep-driving”—i.e., driving a vehicle without being conscious of doing so.

During the defense case, Wagner took the stand and testified that he had been at home watching television, and then he took his medication and fell asleep. According to Wagner, the next thing he remembered was waking up when he hit the tree and his air bag deployed. Wagner asserted that he remembered nothing about getting into a motor vehicle and driving.

Based on this testimony, Wagner’s attorney asked the judge to instruct the jury that the State was required to prove that Wagner consciously drove the motor vehicle. More specifically, Wagner’s attorney asked the judge to give this instruction:

If you find that [Wagner] was under the effects of a prescription medication, [and] that he was not aware of those effects when he consumed the medication, and that he performed an otherwise criminal act while unconscious as a result of this medication, [then] you must find him not guilty of that criminal act.

The trial judge rejected this proposed instruction because the judge ruled that, if Wagner voluntarily took the medication, then Wagner could be found legally responsible for what ensued, even if he was not consciously driving at the time of the crash.

The jury convicted Wagner of both charges, and Wagner then filed this appeal.

Wagner’s primary claim on appeal is that the jury should have been instructed along the lines that Wagner’s attorney proposed—i.e., that if Wagner was sleep-driving, he should be acquitted.

The correct categorization of Wagner’s claim

Although the attorneys and the judge at Wagner’s trial discussed this issue in terms of mens rea—i.e., whether Wagner acted “knowingly” when he drove the motor vehicle—Wagner’s appellate attorney correctly recognizes that Wagner’s proposed defense was actually a claim that Wagner could not be held responsible for the actus reus of driving. Wagner does not claim that his act of driving was “unknowing”. Rather, he claims that his act of driving was “involuntary”.

Normally, a person can not be held criminally responsible for their conduct unless they have engaged in a voluntary act or omission. The term “voluntary act” is defined in AS 11.81.900(b)(66) as “a bodily movement performed consciously as a result of effort and determination”. As we explained in Mooney v. State, 105 P.3d 149, 154 (Alaska App. 2005), the criminal law defines “voluntary act” as a willed movement (or a willed refraining from action) “in the broadest sense of that term”.

But as we are about to explain, a voluntary act is not necessarily a “knowing” act, as that term is used in our criminal code.

Many criminal offenses require proof of a particular type of conduct—e.g., delivering a controlled substance to another person, or warning a fugitive felon of their impending discovery or apprehension. When a crime is defined this way, there will be circumstances when a defendant’s willed actions (their “voluntary” acts) will fit the statutory definition of the prohibited conduct, but the defendant will not have been aware that they were engaging in this defined type of conduct.

For instance, a mail carrier or other delivery person may deliver a letter or package without knowing that it contains a controlled substance. Or someone (a neighbor or a news reporter, for example) may unwittingly say or do something that tips off a fugitive felon to their impending discovery or apprehension. In these instances, the person will have performed a “voluntary act”, but they will not have “knowingly” engaged in the conduct specified in the statute.

This is not the kind of defense that Wagner wished to raise at his trial. Wagner’s attorney did not argue that, even though Wagner knew he was engaging in some form of action, Wagner somehow remained unaware that, by his actions, he was putting a motor vehicle into operation.

Rather than raising a defense of “unknowing” conduct, the defense attorney argued that Wagner did not engage in any conscious action—that Wagner was essentially asleep, and that he was unaware that he was engaged in activity of any kind. This was a claim of involuntariness.

Why we reverse Wagner’s conviction

In State v. Simpson, 53 P.3d 165 (Alaska App. 2002), this Court recognized that even though the voluntariness of a defendant’s conduct is rarely disputed, the requirement of a voluntary act is “an implicit element of all crimes”. Thus, “[i]f voluntariness is actively disputed, the government must prove it.” 53 P.3d at 169.

The criminal law’s concept of involuntariness includes instances where a defendant is rendered unconscious by conditions or circumstances beyond the defendant’s control, if the defendant neither knew nor had reason to anticipate this result. [citations omitted]

Compare Solomon v. State, 227 P.3d 461, 467 (Alaska App. 2010), where this Court ruled that defendants charged with driving under the influence can raise a defense of “unwitting intoxication” if the defendant made “a reasonable, non-negligent mistake concerning the intoxicating nature of the beverage or substance that they ingested”.

Having considered these authorities, […] we conclude Wagner would have a valid defense to the charges of driving under the influence and driving with a revoked license if (1) he took a prescription dose of zolpidem, (2) he was rendered unconscious by this drug and engaged in sleep-driving, and (3) he neither knew nor had reason to anticipate that the drug would have this effect.

[…]

Conclusion

The judgement of the superior Court REVERSED.

[NOTE: Judge Mannheimer, the author of the Wagner opinion authored several of the legal opinions reprinted in this this textbook. Judge Mannheimer intentionally uses the English version of the term “judgement” in his opinions. Its use is not a typographical error.]

Status as a Criminal Act

Generally, a defendant’s status in society is not a criminal act. Status is who the defendant is, not what the defendant does. Similar to punishment for an involuntary act, when the government punishes an individual for their status, the government is targeting an individual for circumstances that may be outside of his or her control. Punishing a person for their status – as opposed to their conduct – may constitute unconstitutional cruel and unusual punishment under certain circumstances.

In Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962), the US Supreme Court held that it is unconstitutional to punish an individual for their status of being a drug addict — even if the drugs themselves are illegal. The Court compared drug addiction to an illness, such as leprosy or venereal disease. Punishing a person for being sick is not only inhumane, but does not deter future criminal conduct. See id at 665-66.

Even though it is unconstitutional to punish a person for their status, the government is entitled to punish a person for their conduct. In Powell v. Texas, 392 U.S. 514 (1968), the US Supreme Court upheld the defendant’s conviction for being “drunk in public,” despite the defendant’s status as an alcoholic. The Court reasoned that a defendant may be convicted of “being drunk in public on a particular occasion” regardless of whether a person is an alcoholic. See id. at 532. Although it may be difficult for an alcoholic to resist the urge to drink, it is not impossible. Such behavior is voluntary. According to Powell, statutes that criminalize voluntary acts that arise from status are constitutional.

Example of a Constitutional Statute Related to Status

In the previous example, Timothy drove home while intoxicated and killed another person. Assume that Timothy is an alcoholic and claims he cannot stop his drinking. Should Timothy be relieved of liability because he is an alcoholic? Holding Timothy criminally responsible for manslaughter is constitutional, irrespective of his alcoholism. Timothy was not punished for being an alcoholic; he was punished for driving while intoxicated and killing a person – a voluntary act. Timothy’s status as an alcoholic may make it more difficult for him to control his drinking, but it does not relieve him from criminal responsibility.

You be the Judge …

Boise, Idaho has a significant and increasing homeless population. Between 2014 and 2106, Boise’s homeless population increased by 15%, and by all accounts, continued to grow. The City of Boise has three homeless shelters, all run by private, nonprofit organizations. The shelters are frequently full and turn away individuals when a person suffering homelessness seeks shelter. In an effort to equitably distribute the shelter services, the three shelters limit the number of consecutive nights any single homeless person may stay at the shelter. To combat the persistence of homelessness, the City of Boise passed two ordinances that criminally punished the act of sleeping outside on public property, whether bare or with a blanket or other basic bedding. Both ordinances authorize a court to impose a monetary fine or jail if violated.

Susan is homeless and frequently relied on Boise’s shelters for housing. Although she has been staying at one of the local shelters, she was involuntarily discharged since she reached the shelter’s 17-day limit for guests. Because she could not go to a shelter, Susan slept in the downtown park. A Boise police officer arrested Susan for sleeping in the park “wrapped in blankets on the ground.” The court found Susan guilty and imposed one day in jail and a $25 fine.

Is Susan’s conviction based on her status of being homeless or based on her voluntary act of sleeping outside? Check your answer using the answer key at the end of the chapter.

Possession as a Criminal Act

Possession, even though it is passive conduct, is still considered a criminal act. Nearly every jurisdiction criminalizes the possession of illegal contraband. The most common objects that are criminalized include drugs, weapons, or specific criminal tools (i.e., burglary tools). Possession frequently falls within one of several categories: active, constructive, joint, and fleeting possession.

Actual possession means the defendant has direct physical control, care, and management of a physical item. Generally, this means the item is on, or very near, the person. Constructive possession means that although the item is not on the defendant’s person, it is within the defendant’s area of control – that is, the defendant has the right or authority to exercise control or dominion over the item. Consider a person’s ‘possession’ of their house or automobile while the person is at work. Even though the person is not physically present at their home, the person has constructive possession over the items inside the home – that is, the person has the authority to control the item. Possession can also be sole or joint. Joint possession is when two or more people have actual or constructive possession over an item. Fleeting possession is when a person physically possesses contraband innocently and momentarily, with the intent to turn the item over to the lawful authority (i.e., police). Fleeting possession is generally not criminal. For example, if a person discovers discarded heroin on a sidewalk, the person could pick up the illegal drugs with the intention of delivering it to law enforcement. If the person’s intention was genuinely innocent and momentary, the felon’s possession would be considered fleeting, and he would not be guilty of a crime. See e.g., Jordan v. State, 819 P.2d 39, 42-43 (Alaska App. 1991).

Momentary Possession Must be Truly Innocent

Crabtree and Baker were partners in a woodcutting business near Fairbanks. After Baker unsuccessfully tried to collect the $180 that Crabtree owed him, Baker took Crabtree’s handgun. Baker immediately took the handgun to a local pawnshop, where he pawned the gun for $135. While Baker was at the pawnshop, Crabtree called the police. When the police arrived, Baker explained that he was merely collecting on an outstanding debt and he had the gun for thirty minutes – the amount of time it took to drive from the business to the pawnshop. The police discovered Baker was a felon and charged him with one count of being a felon-in-possession of a firearm. AS 11.61.200(a)(1). A jury convicted him.

On appeal, Baker claimed that his possession was “fleeting” and that he only possessed the gun long enough to transport it to the pawnshop. The Court rejected Baker’s argument: “We are satisfied that the legislature did not intend to permit felons to possess prohibited weapons as collateral for debt, nor did it intend to immunize knowing possession of a weapon for the time necessary to pawn it. … [Baker] knowingly took [the gun] from Crabtree, pawned it, and retained the pawn ticket until he turned it over to the police. Under these circumstances, a reasonable jury could not find momentary or inadvertent possession of the handgun.” See Baker v. State, 781 P.2d 1368, 1369 (Alaska App. 1989).

Because possession can be either actual or constructive, both of which can be abstract concepts, courts have struggled to define when a person may be criminally liable for a possessory offense if the person merely has the ability or power to exercise control over an item versus whether the person did exercise the control over the item. The following case, Alex v. State, 127 P.3d 847 (Alaska App. 2006), is a great example of the dilemma surrounding possession.

Alex v. State, 127 P.3d 847 (Alaska App. 2006)

127 P.3d 847

Court of Appeals of Alaska.

Timothy G. ALEX, Appellant,

v.

STATE of Alaska, Appellee.

No. A–8839.

Jan. 13, 2006.

Rehearing Denied Feb. 16, 2006.

OPINION

MANNHEIMER, Judge.

Timothy G. Alex was convicted of weapons offenses after the police recovered a pistol from under the passenger seat of the vehicle in which Alex was riding. At trial, Alex claimed that he had no idea that the pistol was there.

Toward the close of the trial, Alex’s trial judge proposed to instruct the jury that a person is in “constructive possession” of an item if the person has “the power to exercise dominion or control” over that item. Alex’s defense attorney argued that proof of a person’s power to exert dominion or control over an object was not enough—that the State was also obliged to prove that the person actually exercised this power, or at least intended to exercise it. After listening to the defense attorney’s argument, the trial judge decided not to alter the wording of the jury instruction. In this appeal, Alex renews his contention that the instruction, as given, was an erroneous statement of the law.

It is not clear that this case even raises an issue of constructive possession. As we explain in more detail below, the item in question—a semi-automatic assault pistol—was found underneath the passenger seat of the vehicle in which Alex was riding (as the passenger). It would therefore appear that, if Alex indeed possessed this pistol, he had actual possession of it, not “constructive” possession.

The fact that the parties to this appeal have framed the issue in terms of “constructive possession” may stem from the fact that this concept suffers from a lack of precision. As the United States Supreme Court has noted, the two concepts of “actual” possession and “constructive” possession “often so shade into one another that it is difficult to say where one ends and the other begins”. Indeed, some legal commentators have suggested that the words employed in Alex’s case to define constructive possession—“dominion” and “control”—do not really provide a workable definition of this concept; rather, these words “are nothing more than labels used by courts to characterize given sets of facts”.

There is, in fact, some case law to support Alex’s contention that a person should not be convicted of constructively possessing an object merely because the person could have exercised dominion or control over the object—that the government must also prove either that the person did exercise dominion or control over the object, or at least intended to do so.

However, because of the way Alex’s case was litigated, we are convinced that the jury’s decision did not turn on this distinction. As we explain here, the jury’s verdicts demonstrate that the jurors must have concluded, not only that Alex knew about the pistol under his seat, but also that Alex possessed that pistol[.] Thus, even assuming that the jury instruction on “constructive possession” should have expressly required proof that Alex had already exercised dominion or control over the pistol, or that he intended to do so, this error had no effect on the jury’s decision. We accordingly affirm Alex’s conviction.

Underlying facts

On the afternoon of December 14, 2002, Anchorage Police Officer Leonard Torres made a traffic stop of a vehicle. When Torres asked to see the vehicle registration, the driver, Darryl Wilson, told the passenger, Timothy Alex, to retrieve the registration from the glove compartment. Torres moved to the passenger side of the vehicle so that he could “see … what [Alex] was reaching for in the glove compartment”. When he did so, Torres observed that Alex had an open bottle of beer between his legs.

Wilson, too, had apparently been drinking. Moreover, when Torres ran Wilson’s and Alex’s names through the computer, he learned that both men were on felony probation. Torres called for backup.

Torres focused his attention on Wilson while two backup officers, Kevin Armstrong and Jeff Carson, asked Alex to step outside the vehicle. During their conversation with Alex, one of the officers asked if there were any firearms in the vehicle. Alex told the officers that there was a firearm under the passenger seat. Carson looked on the floor of the vehicle, underneath where Alex had been sitting, and discovered a “Tec 9” (i.e., an Intratec DC–9, a 9–mm semi-automatic assault pistol).

Because Alex was a convicted felon, he was prohibited from possessing a concealable firearm.

[…]

Based on these events, Alex was indicted for … third-degree weapons misconduct (possession of a concealable firearm by a felon).

Alex did not testify at his trial. However, Alex’s attorney elicited testimony (during cross-examination of the police officers) that (1) both Wilson and Alex told the police that the Tec–9 pistol belonged to the owner of the vehicle, a man named Earl Smith, and that (2) when the police spoke to Earl Smith about this weapon, he confirmed that the Tec–9 pistol did, in fact, belong to him. Indeed, Smith declared that he had never told Wilson and Alex that there was a pistol in the vehicle.

[…]

At the end of the trial, during the defense summation, Alex’s attorney told the jury that Smith’s account was truthful: that the pistol belonged to Smith, and that Alex had not known that the pistol was in the vehicle.

The defense attorney acknowledged that two police officers (Armstrong and Carson) had testified that Alex did know about the pistol—that, in fact, Alex told them that the weapon was present in the vehicle, and that he disclosed the weapon’s location under the passenger seat. But the defense attorney told the jurors that the officers were lying—that the officers were saying this only because they knew that the State’s “whole case” depended on the argument that Alex must have knowingly possessed the weapon “because he knew it was there”.

The defense attorney repeatedly declared that the jurors should disbelieve the officers’ testimony on this point. She told the jurors: “Look at the foundation of [Alex’s] alleged confession [that there was gun underneath the seat]. Look at the root of that information. It’s tainted; it’s skewed; it’s biased; it’s untrustworthy.” A few moments later, she told the jurors: “We have the shadiest confession, completely untrustworthy.”

A little later in her summation, the defense attorney returned to this theme. She told the jurors that, because Alex was merely a passenger in the car (not the owner of the vehicle, and not the driver), the police must have known that they could not charge and convict Alex of the weapons offenses unless they had a confession—i.e., Alex’s admission that he knew that the pistol was under his seat.

Defense Attorney: So they [purportedly] get [the needed confession]. [But] did they? I don’t know. Do you know? I would think not.

…

[The police] call[ed] Mr. Earl Smith [to ask him about the gun]. And … what did Mr. Earl Smith say? “That’s my gun. [Wilson and Alex] don’t know that it’s in there.”

These arguments proved unavailing; the jury convicted Alex of the [weapon offense].

[…]

The potential problem with the definition of “constructive possession”, and why we conclude that any error was harmless

In retrospect (and after briefing), it is easier to see the potential problem caused by including the words “have the power to” in the definition of “constructive possession”.

[…]

Alaska cases have never directly addressed [the definition of constructive possession]. In [a prior opinion], the Alaska Supreme Court declared that “possession” was “a common term with a generally accepted meaning: having or holding property in one’s power; the exercise of dominion over property.” But the supreme court may have been overly optimistic when it declared that “possession” had a common, generally accepted meaning.

There is an ambiguity in the word “power”. This word can refer to a person’s right or authority to exert control, but it can also refer to anything a person might be physically capable of doing if not impeded by countervailing force. Thus, if “constructive possession” is defined as the “power” to exercise dominion or control over an object, this definition potentially poses problems—because it suggests that a person could be convicted of possessing contraband merely because the person knew of the contraband and had physical access to it, even though the person had no intention or right to exercise control over it.

For example, the children of a household might know that there is beer in the refrigerator or liquor in the cupboard. Assuming that it is within the children’s physical power to gain access to these alcoholic beverages, one might argue that the children are in “constructive possession” of these beverages—and thus guilty of a crime [of] minor in possession of alcoholic beverages – because the children have “the power to exercise dominion or control” over the beverages.

To avoid results like this, some courts have worded their definitions of “constructive possession” in terms of a person’s “authority” or “right” to exert control over the item in question. … Other courts have worded the test as the defendant’s “power and intention ” to exert control or dominion over the object.

This same type of problem might have arisen in Alex’s case if the case had been litigated differently. For example, given the facts of the case, one can imagine Alex conceding that he was aware of the pistol under his seat, but then asserting that he had no connection to the pistol and that he only became aware of its presence underneath his seat when, during his ride in the vehicle, the pistol bumped against his feet.

But this was not the strategy that Alex’s defense attorney adopted at trial. Instead of conceding that Alex knew that there was a pistol under his seat, Alex’s attorney denied that Alex knew about the pistol, and further denied that Alex had ever said anything to the police about the weapon. The defense attorney relied on Earl Smith’s statement that Alex and Wilson did not know that there was a firearm in the vehicle, and the attorney argued that the police officers had lied when they testified that Alex directed them to the weapon.

[…]

Given this defense, it is unlikely that the claimed ambiguity or error in the jury instruction defining “constructive possession” affected the jury’s decision—because the alleged flaw in the jury instruction would make a difference only if Alex conceded that he was aware of the assault pistol under his seat.

[…]

Conclusion

As we have explained here, Alex’s brief to this Court identifies a potential problem in the wording of the “constructive possession” instruction that was given at his trial. … But … we conclude that this potential problem in the wording of the jury instruction had no effect on the jury’s verdicts. Accordingly, the judgement of the superior court is AFFIRMED.

The More You Know …

In response to the dilemma highlighted in Alex v. State, Law Professor Chad Flanders argues that Alaska judges should view actual and constructive possession as separate and distinct concepts and not along a continuum. Actual possession includes both current and past physical possession. A person is in actual possession of an item if they have the item on their person or if they had previously possessed the item. Past physical possession is still actual possession (not constructive possession). Constructive possession, on the other hand, should be reserved for those cases where the person has not physically possessed the item but has a legal right (or a functional equivalent) over the item. In the end, Professor Flanders proposes a new “possession” jury instruction to address this problem.

The law recognizes two kinds of possession: actual possession and constructive possession. Actual possession means to have direct physical control, care, or management of a thing. Actual possession does not have to be current possession; it is enough for actual possession to show that the defendant recently had physical control, care, and management over the item.

A person not in actual possession may have constructive possession of an item. Constructive possession means to have ownership of an item, or power and authority over that item or over a place where that item is such that one can without difficulty or opposition reduce it to one’s direct physical control.

See id at 21.

Professor Flanders provides several good examples and explanations of these issues in C. Flanders, “Actual” and “Constructive” Possession in Alaska: Clarifying the Doctrine, 36 Alaska L. Rev. 1 (2019). The article is available via Westlaw Campus Research through the University of Alaska Anchorage Consortium Library using your student UA credentials.

Omission to Act

Generally speaking, the law does not impose criminal liability on a person’s failure to act. Under the American Bystander Rule, a person has no responsibility to rescue or summon aid for another person who is in danger, even though society may recognize a moral obligation to intervene. “Thus, an Olympic swimmer may be deemed by the community as a shameful coward, or worse, for not rescuing a drowning child in the neighbor’s pool, but she is not a criminal.” See State ex. rel. Kuntz v. Montana Thirteenth Judicial District Court, 995 P.2d 951, 955 (Mont. 2000). Prosecuting individuals for failing to act is rare since the government is reluctant to compel individuals to put themselves in harm’s way and such circumstances are difficult to legislate.

The American Bystander Rule is not without exceptions. Criminal liability may be imposed for voluntary omissions to act if the law imposes a duty to act. This legal duty becomes an element of the crime, which the prosecution must prove beyond a reasonable doubt, along with the circumstances of the defendant’s inaction. Failure to act is criminal in only four situations: (1) when there is a statute that creates a legal duty to act, (2) when there is a special relationship between the parties that creates a legal duty to act, (3) when there is a contract that creates a legal duty to act, or (4) when a person has assumed a duty by voluntarily intervening in a situation to assist another person. See e.g., Sickel v. State, 363 P.3d 115 (Alaska App. 2015). Precise legal duties to act vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

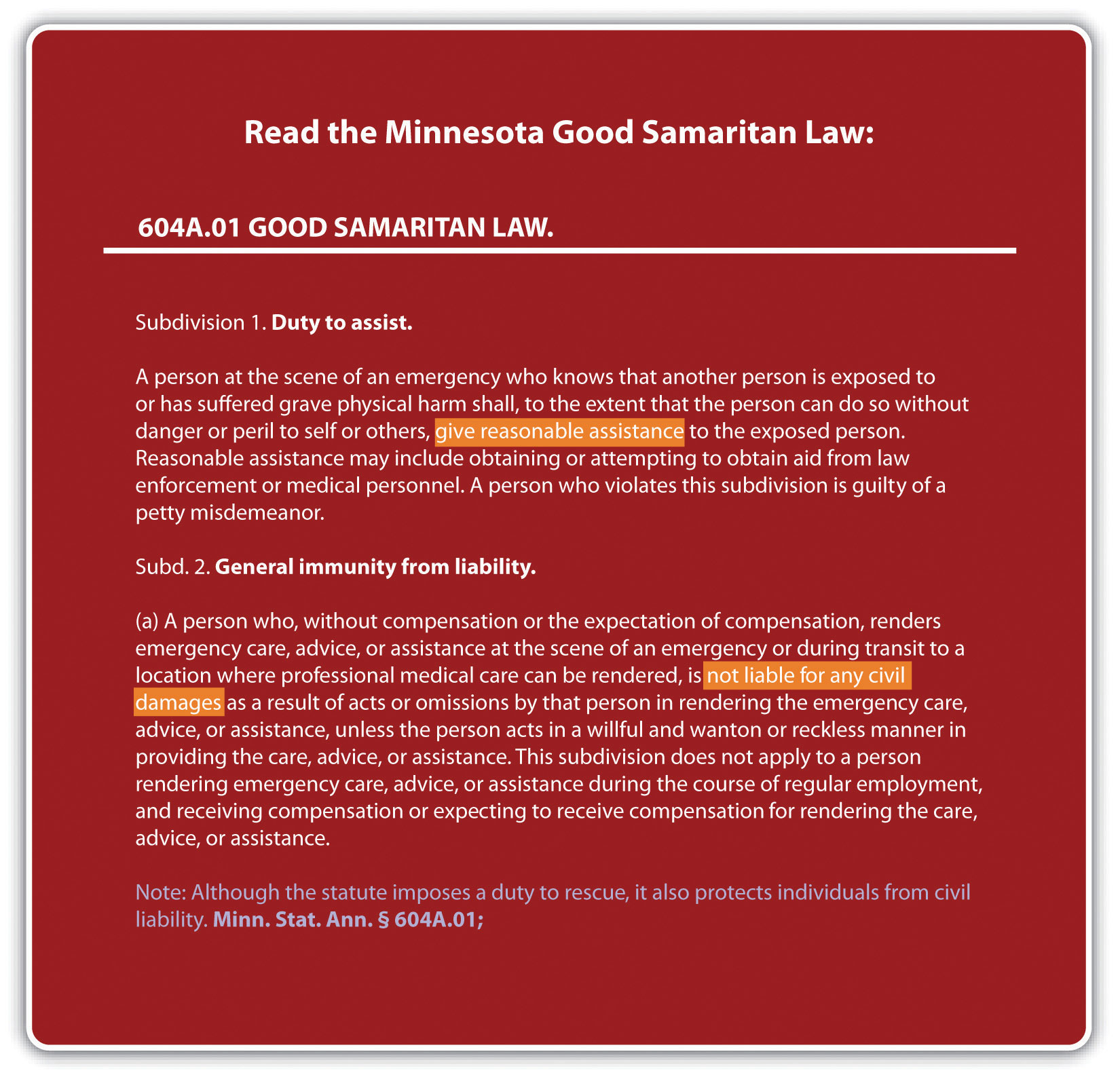

Some states have superseded the general rule by enacting Good Samaritan statutes that create a duty to assist those involved in an accident or emergency situation. Good Samaritan statutes typically contain provisions that insulate the actor from civil liability when providing assistance. See generally Minn. Stat. §604A.01 (2001).

Duty to Act Based on a Statute

When a duty to act is statutory, it usually concerns a paramount government interest. Some common examples include the duty to file state or federal tax returns, the duty of certain healthcare personnel to report specific injuries, and the duty to report suspected child abuse. For example, Alaska obligates public and private school teachers to report cases of suspected child abuse to the Office of Child Services (OCS) or law enforcement. AS 47.17.020. School teachers who fail to report cases of suspected abuse are guilty of a Class A misdemeanor, punishable by up to one year in jail. AS 47.17.068.

Figure 4.3 Alaska Criminal Code

![The following persons who, in the performance of their occupational duties, […] have reasonable cause to suspect that a child has suffered harm as a result of child abuse or neglect shall immediately report the harm to the nearest office of the [Office of Child Services] and, if the harm appears to be a result of a suspected sex offense, shall immediately report the harm to the nearest law enforcement agency: (1) practitioners of the healing arts; (2) school teachers and school administrative staff members, including athletic coaches, of public and private ` schools; [and] (3) –(9) [omitted for brevity].](https://pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/2614/2022/09/47.17.020-diagram-edit.jpg)

Duty to Act Based on a Special Relationship

A special relationship may also create a legal duty to act. The most common special relationships are parent-child, spouse-spouse, and employer-employee. Often, the rationale for creating a legal duty to act when people are in a special relationship is the dependence of one individual on another. Irrespective of the moral obligation a parent may have towards their child, the criminal law imposes a legal obligation to provide food, clothing, shelter, and medical care since the child is dependent on their parents for their basic needs. Children do not have the ability to protect themselves, and as we will see in Michael v. State, 767 P.2d 193 (Alaska App. 1998) reversed on other grounds 805 P.2d 371 (Alaska 1991), parents can be held criminally liable for failing to protect their children from harm.

Duty to Act Based on a Contract

A duty to act can be based on a contract between the defendant and another party. The most prevalent examples would be a physician’s contractual duty to help a patient or a lifeguard’s duty to save someone who is drowning. Keep in mind that experts who are not contractually bound can ignore an individual’s pleas for help without committing a crime, no matter how morally abhorrent that may seem. Remember, an Olympic swimmer can watch someone drown if there is no statute, contract, or special relationship that creates a legal duty to act, but if the Olympic swimmer is employed as a lifeguard, criminal liability may attach.

Duty to Act Based on the Assumption of Duty

Criminal liability may attach if a person fails to continue to provide aid, once assistance has started. Similar to the duty based on a special relationship, the duty to continue to provide aid is rooted in the person’s assumption of the victim’s care and the victim’s continued dependence. It is unlikely that another person will come along to help once the defendant has begun providing assistance. For example, a driver who picks up an injured person on the street, with the intent of taking them to the hospital, may be criminally liable if the driver changes his mind and leaves the person somewhere other than the hospital. See generally U.S. v. Hataley, 130 F.3d 1399, 1406 (10th Cir. 1997).

Example of a Failure to Act That Is Noncriminal

Recall the example where Clara and Linda are shopping together and Clara stands by and watches Linda put a bra in her purse without paying for it. In this example, Clara does not have a duty to report Linda for shoplifting. Clara does not have a contractual duty to report a crime because she is not a store security guard obligated by an employment contract. Nor does she have a special relationship with the store mandating such a report. Unless a statute or ordinance exists to force individuals to report crimes committed in their presence, which is extremely unlikely, Clara can legally observe Linda’s shoplifting without reporting it. Of course, if Clara assists Linda with the shoplifting, she is likely criminally accountable for Linda’s criminal conduct, but we’ll discuss accountability in Chapter 5, “Parties to Crimes.”

Example of a Failure to Act That Is Criminal

Penelope stands on the shore at a public beach and watches as a child drowns. If Penelope’s state had a Good Samaritan law, she may have a duty to help the child based on a statute. If Penelope is the lifeguard, she may have a duty to save the child based on a contract. If Penelope is the child’s mother, she may have a duty to provide assistance based on their special relationship. If Penelope began to rescue the child in the ocean, she may have a duty to continue her rescue. If Penelope is just a bystander, and no Good Samaritan law is in force, she has no duty to act and cannot be criminally prosecuted if the child suffers harm or drowns.

Michael v. State, 767 P.2d 193 (Alaska App. 1998)

As you read the next case, Michael v. State, consider that one of the primary purposes of modern criminal statutes is to provide notice to individuals as to what is, and is not, criminal. The criminal law does not explain what a person may do, but instead, what a person may not do (or in the context of omissions, what a person must do). How does a parent know when they must protect their child? The following case begins to address this issue. In the next section you will read, Willis v. State, 57 P.3d 688 (Alaska App. 2002), which will address how the government proves a parent violated their duty to protect.

767 P.2d 193

Court of Appeals of Alaska.

Steven A. MICHAEL, Appellant,

v.

STATE of Alaska, Appellee.

No. A–2041.

Dec. 23, 1988.

OPINION

COATS, Judge.

Loreli and Steven Michael were each indicted on thirteen counts of assault in the first degree. Each count of the indictment charged that Loreli and Steven Michael had assaulted their daughter D.M. Each count of the indictment represented a bone that had been broken in the body of their daughter.

[…]

Loreli and Steven Michael were tried jointly in October, 1986. Acting Superior Court Judge Alexander O. Bryner presided over the court trial. Judge Bryner found Loreli Michael guilty of three counts of first-degree assault. He concluded that Loreli Michael had personally inflicted D.M.’s injuries. He sentenced her to ten years with three years suspended on each count, placing her on probation for five years following her release from confinement. … Judge Bryner found that Steven Michael had not personally inflicted the injuries on his daughter and had not acted as an accomplice to the infliction of D.M.’s injuries. However, Judge Bryner found that Steven Michael had caused harm to his daughter by failing to prevent his wife from injuring D.M. and by failing to obtain medical aid. He found Steven Michael guilty of two counts of second-degree assault, a lesser-included offense. Judge Bryner sentenced Steven Michael to four years imprisonment with two years suspended, placing Michael on probation for five years following his release from confinement. […] Steven Michael now appeals, arguing that (1) he could not properly be convicted of assault on the theory that he did not act to prevent his daughter’s injuries[.] We affirm [Steven Michael’s] convictions.

D.M. was born on November 5, 1985, to Loreli and Steven Michael. On January 5, 1986, the Michaels brought D.M. into the emergency room at the Elmendorf Air Force Base hospital because her leg was red and swollen. Dr. Carole Buchholz examined her and ordered x-rays.

Upon examining the x-rays, Dr. Buchholz saw “obvious fractures of all four bones in the lower legs,” two bones in each leg. Dr. Buchholz ordered additional x-rays, which showed many more broken bones: both femurs (upper legs), the upper and lower bones of both arms, and at least nine ribs. Dr. Steven Diehl, a radiologist, was brought in to review the x-rays. Dr. Diehl concluded that D.M. had suffered multiple fractures and that her bones were in different stages of recovery.

Drs. Buchholz and Diehl testified that a baby’s bones heal quite rapidly if broken. The doctors were able, therefore, to determine the approximate date that each of the fractures was inflicted. Some of the fractures were very recent; others were several weeks old. The left tibia (lower leg) had been fractured twice, at two different times. The rib fractures had been inflicted at different times. Several other bones had been fractured more than once. The nature and number of the fractures and the amount of force required to inflict them excluded accidental causes. D.M. also had a bruise on the back of her left shoulder, and two burns on her left forearm. She also had broken blood vessels on her face and neck.

Loreli Michael had been the baby’s primary caretaker. She stayed home with the baby during the day. Steven Michael, who was in the Army, was out of town on field maneuvers for about two weeks beginning December 5. He returned home sometime between December 14 and 20. From his return until January 5, he would on some days spend long hours on duty, but on other days would spend a substantial amount of time at home. Although Loreli Michael did most of the caretaking—diaper changing and the like—when he was home, Steven Michael occasionally performed these duties.

Loreli Michael told Sandra Csaszar, the Division of Family and Youth Services social worker who investigated the case, that D.M. had always been in the presence of one or the other parent from the time she left the hospital after her birth until January 5. She had never been left with a babysitter.

Based upon the foregoing, and other evidence, Judge Bryner concluded that Loreli Michael was guilty of three counts of assault in the first degree. He concluded that Loreli Michael had directly assaulted D.M., personally causing D.M.’s injuries.

[At trial, the state’s theory of criminal liability] for Steven Michael was that Michael had breached his legal duty to aid and assist his child because he did not aid his daughter when he knew that she was physically mistreated and abused by his wife. [Judge Bryner found Michael guilty on this] theory [noting,]

Mr. Michael had a legal duty to aid and assist his child if she was under the threat or risk of physical damage or assault—from any person, including his wife. I find that that duty existed both under Alaska statutes as well as under common law. Second, I find that Mr. Michael did not aid and did not help his daughter when she was in fact physically mistreated and abused by his wife. Third, I find that Mr. Michael’s failure to act was knowing. In other words, I find that Mr. Michael was capable of rescuing and assisting his daughter. And I find that he knew that he was capable and—could have rescued her. I find specifically that he was aware of a substantial probability that his daughter was being mistreated, or physically abused by his wife. And that he failed to act in the face of … that awareness. As a result, I further find that as a result of his failure to act, that his daughter suffered serious physical injury.

….

Mr. Michael was aware, after December 20th, … of [a] substantial probability that his daughter was … under a risk of physical attack and assault from his wife of some sort. Knowing that risk[,] I find that the failure to render assistance under those circumstances constitutes a gross departure [or] deviation from the standard of conduct that would be expected of … ordinary people in the normal everyday conduct of their affairs under similar circumstances. And for that reason I do find that Mr. Michael, in failing to take any action on behalf of his … daughter, acted recklessly.

Stephen Michael argues that he could not properly be convicted for assault for failing to act to protect his child. The question which he raises is a question of statutory interpretation. … Neither the Alaska Supreme Court nor this court has previously decided this question; this is a case of first impression in this jurisdiction.

[…]

We … turn to the common law and to decisions of other state courts to determine how other courts have resolved similar problems. In general, under the common law a person did not face criminal liability for the failure to aid another person. However, the common law created a clear exception to this general rule where there was a parent-child relationship. A parent had a clear duty to aid his child.

Although there does not seem to be extensive case law directly on point in this area of the law, the case law that is available appears to be unanimous in establishing the duty of a parent to act to protect his child. […] Furthermore, other Alaska statutes establish a duty for a parent to care for a child. AS 11.51.120(a) provides misdemeanor criminal penalties where “a person legally charged with the support of a child under 18 years of age … fails without lawful excuse to provide support for the child.” AS 11.51.120(b) defines support to include “necessary food, care, clothing, shelter, medical attention, and education.”

We conclude that Steven Michael could properly be convicted of assault in the second degree[.] In interpreting [the law], the critical question before us is whether Steven Michael’s failure to take reasonable actions to protect his child from serious physical injury by Loreli Michael can be said to have caused D.M.’s injuries. Although generally a person has no duty to act to protect another, we find that the common law and Alaska statutes establish a clear duty upon a parent to protect his child. It seems clear under the law that where the parent fails to carry out this duty and the child is injured as a result, the parent has caused the child’s injuries and may be held criminally liable.

[…]

The conviction is AFFIRMED.

Exercises

Answer the following question. Check your answer using the answer key at the end of the chapter.

- Jacqueline is diagnosed with epilepsy two years after receiving her driver’s license. While driving to a concert, Jacqueline suffers an epileptic seizure and crashes into another vehicle, injuring both of its occupants. Can Jacqueline be convicted of a crime in this situation? Why or why not?