Criminal Intent (Culpable Mental State)

All crimes, with a few exceptions to be discussed shortly (e.g., strict liability), include a culpable mental state or mens rea. Mens rea refers to the mental state of the accused at the time they committed the offense. Put another way, mens rea describes the purposefulness – or lack thereof – of the defendant’s conduct. A person’s level of criminal intent forms the basis of grading a particular offense – that is, the more “evil” a person’s intent, the more serious the offense is considered in the eyes of the law.

A culpable mental state is an essential element for most crimes. If the government is unable to prove that the defendant acted with the applicable culpable mental state, the person is not guilty of the offense. AS 11.81.600(b). It is the same as the defendant not committing the act. Mental state is different than criminal thoughts or motive. Thoughts – no matter how evil – cannot be criminalized. Motive, while potentially helpful in understanding why a person committed a crime, is never something the government is required to prove. Let’s look at first-degree murder as an example.

Figure 4.4 Alaska Criminal Code – Murder in the First Degree

![AS 11.41.100. Murder in the first degree. A person commits the crime of murder in the first degree if With intent to cause the death of another person, the person (a) causes the death of any person[.]](https://pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/2614/2021/05/11.41.100-diagram.jpg)

As you can see, first-degree murder must be committed intentionally. The defendant must intend to cause the death of the victim – accidentally causing death is insufficient. Likewise, intending to seriously injure the victim is insufficient. The defendant must have a conscious objective to cause the victim’s death.

All jurisdictions vary in their approach to defining a particular culpable mental state. For clarity, this section explores the common law definitions of criminal intent before exploring the different culpable mental states under the Alaska Criminal Code.

Example of Noncriminal Thoughts

Brianna, a housecleaner, fantasizes about killing her elderly client Phoebe and stealing all her jewelry. Brianna writes her thoughts in a diary, documenting how she intends to rig the gas line so that gas is pumped into the house all night while Phoebe is sleeping. Brianna includes the date that she wants to kill Phoebe in her most recent diary entry. As Brianna leaves Phoebe’s house, her diary accidentally falls out of her purse. Later, Phoebe finds the diary on the floor and reads it. Phoebe calls the police, gives them Brianna’s diary, and insists they arrest Brianna for attempted murder. Although Brianna’s murder plot is sinister and is documented in her diary, charging Brianna with attempted murder is inappropriate at this point. Brianna cannot be criminally punished for her thoughts alone. If Brianna took a substantial step toward killing Phoebe, an attempted murder charge might be appropriate. However, at this stage, Brianna is only planning a crime, not committing a crime. You will explore the crime of attempt in Chapter 6, “Inchoate Offenses.”

Motive

Remember, intent should not be confused with motive. The criminal law never requires the government to prove motive. Motive, or the reason the defendant commits a criminal act, can help explain a defendant’s actions or culpable mental state, but motive alone cannot act as a substitute for the applicable mens rea. Motive is never an element of a crime.

Common Law Mental States

At common law, all crimes require the criminal act be committed with a “guilty mind.” The level of one’s “guilty mind” resulted in three culpable mental states ranked in order of culpability: malice aforethought, specific intent, and general intent. Although individual statutes and cases use different words to indicate particular criminal intent, what follows is a basic description of the intent definition adopted by many jurisdictions. Further, even though Alaska has abolished the common law culpable mental states, they are routinely referenced in caselaw. For this reason, a general understanding of common law is necessary for a complete understanding of criminal law.

Malice Aforethought

Malice aforethought is a special common law mental state designated for only one crime: murder. Malice aforethought means “intent to kill” without adequate justification. We will explore justifications in subsequent chapters, but for now, recognize that malice aforethought is the specific intent to kill. Society considers acting with a specific intent to kill another human being the most evil of all intents, so individuals who act with malice aforethought generally receive the most severe punishment. Malice aforethought and criminal homicide are discussed in detail in Chapter 9, “Criminal Homicide.”

Specific Intent

Specific intent is the highest level of culpability other than malice aforethought. Specific intent refers to an intent to accomplish a specific act prohibited by law. Typically, specific intent means that the defendant acts with a more sophisticated level of awareness. The crimes of theft and larceny are historically specific intent crimes. Theft requires the “intent to permanently deprive” another of property. The statute requires more than simply taking the property, the law requires the defendant to intend to keep the property permanently. This is the difference between criminal theft and simply borrowing someone’s property without consent. For example, if Pauline borrows Peter’s razor to shave her legs, she has “taken property of another,” but she has not committed the crime of theft for the simple reason that she intends to return the property after use.

General Intent

General intent is less sophisticated than specific intent. General intent crimes are easier to prove. A basic definition of general intent is the intent to perform the criminal act or actus reus. For example, a person commits the crime of second-degree harassment if the person “subjects another person to offensive physical contact.” AS 11.61.120(a)(5). This statute describes a general intent crime. To be guilty of harassment, the defendant must recklessly cause harmful or offensive contact. The defendant does not have to desire that the contact produces a specific result, such as scarring, or death; nor does the defendant need awareness that the physical contact is illegal.

Alaska’s Mental States

Alaska divides criminal intent into five culpable mental states listed in order of culpability: intentionally, knowingly, extreme recklessness, recklessness, and criminally negligence. Although there are five culpable mental states under Alaska law, the criminal code only defines four. The fifth – extreme recklessness – is defined by caselaw.

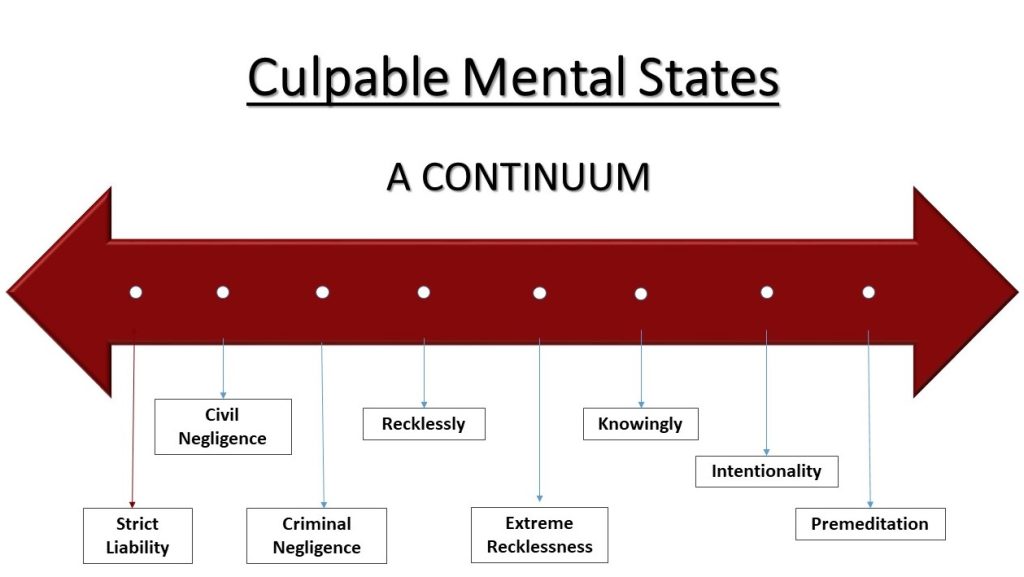

It can be helpful to think of criminal intent as a continuum with no intent (i.e., strict liability) on one end and premeditation on the other end.

Figure 4.5 Culpable Mental State Continuum

Intentionally

A defendant acts intentionally if he has a conscious objective to cause a particular result. AS 11.81.900(a)(1). Put another way, the defendant intends to engage in conduct of that nature and intends to cause a certain result. Intentionally resembles specific intent to cause harm, discussed previously. Although the defendant must intend to cause a particular result, the person’s intent need not be the person’s only objective. A person can, and frequently does, have multiple intents. For example, consider the person who walks in on their spouse and lover engaged in a sexual act. The person may, in a moment of rage, form an intent to kill their spouse and their spouse’s lover. The intent to kill one person (e.g., the spouse), does not mean the person does not also hold an intent to kill another person (e.g., the lover). Also, take note that acting intentionality is not the same as acting deliberately, or premeditatively. Alaska law does not require a person to premediate (i.e., plan) the criminal act. Intentionality can – and frequently does – form in an instant.

Knowingly

Knowingly indicates that the defendant is substantially aware of the nature of the act and its probable consequences. AS 11.81.900(a)(2). Knowingly differs from intentionally in that the defendant is not acting to cause a certain result but is acting with the awareness that the result is practically certain to occur. Alaska law describes knowingly as follows: “A person acts ‘knowingly’ with respect to conduct … when the person is aware that the conduct is of that nature; … knowledge is established if a person is aware of a substantial probability of its existence, unless person actually believes it does not exist[.]” AS 11.81.900(a)(2).

Example of Knowingly

Victor brags to his girlfriend Tanya that he can shoot into a densely packed crowd of people on the subway train without hitting any of them. Tanya dares Victor to try it. Victor takes his pistol to the subway train, aims at a group of people standing with their backs to him, and shoots. As he shoots, Victor tells Tanya, “watch how close I can get without hitting them!” A bullet strikes and kills Monica, who was standing in the group. In this case, Victor did not intend to shoot Monica. In fact, Victor’s goal was to shoot and miss all the standing subway passengers. However, Victor was aware that he was shooting a loaded gun (the nature of the act) and was substantially certain that shooting into a crowd would result in somebody getting hurt or killed. Victor acted knowingly under Alaska law. Victor is likely guilty of second-degree murder. AS 11.41.110(a)(1).

Extreme Recklessness

As mentioned before, extreme recklessness is not one of the four defined culpable mental states in the code but instead a creature of statutory interpretation (case law). The criminal code refers to extreme recklessness as “conduct manifesting an extreme indifference to the value of human life.” See generally Neitzel v. State, 655 P.2d 325, 337 (Alaska App. 1982).

Very few crimes require the defendant act with extreme recklessness. In fact, Alaska only recognizes three offenses that include this mental state – second-degree murder, first-degree assault, and murder of an unborn child. AS 11.41.110(a)(2), 11.41.200(a)(3), and 11.41.150(a)(4), respectively.

The mental state requires the jury to assess the level of recklessness of the defendant’s conduct. The jury must weigh the social utility of the defendant’s conduct (if any) against the precaution the defendant took to minimize the apparent risks. For example, playing “Russian Roulette,” in which the participant has a 16.7% chance of being killed and an 83.3% chance of not being killed, is incredibly dangerous and completely lacks any social utility. On the other hand, the law recognizes that there may be some social utility in firing a gun at an attacking bear in an attempt to rescue a victim even if the bullet strikes the victim, not the bear. The law recognizes that the social utility of this latter example may outweigh the magnitude of the risk. See id. Whether particular acts constitute extreme recklessness is a question of fact for the trier of fact (like all culpable mental states).

We will explore this mental state in more detail in Chapter 9, “Criminal Homicide”.

Example of Extreme Recklessness

Victor and his girlfriend Tanya go camping for the weekend with friends. Late one night, Victor, Tanya, and friends are sitting around the campfire playing with their pistols. Unbeknownst to Victor, Tanya crawls into the tent to go to sleep. Victor, mistakenly believing the tent is empty, shoots into the tent to be funny. One of the bullets strikes Tanya, killing her instantly. In this case, Victor did not intend to shoot Tanya, nor was Victor substantially certain that his errant bullet would kill Tanya. Instead, Victor likely acted with extreme recklessness since there was little social utility to his conduct (i.e., there was no reason to shoot into a tent not knowing if it was occupied) and Victor took no steps to ensure that it was safe to shoot. Under these circumstances, Victor likely engaged in conduct that caused Tanya’s death under circumstances that manifest an extreme indifference to human life – that is, with extreme recklessness. Victor is guilty of second-degree murder. AS 11.41.110(a)(2).

Recklessly

Recklessly is a lower level of culpability than knowingly. The degree of risk awareness is key to distinguishing a reckless intent crime from a knowing intent crime. A defendant acts recklessly if they consciously disregard a substantial and unjustifiable risk that the bad result or harm will occur. AS 11.81.900(a)(3). This is different from a knowing intent crime, where the defendant must be “substantially certain” of the bad results. The reckless intent test is two-pronged. First, the defendant must consciously disregard a substantial risk of harm. The first prong is subjective; the defendant must know of the substantial risk and consciously disregard it. This risk must be unjustifiable, meaning that there is no valid reason for the risk. The second prong is objective; the defendant’s disregard of the risk must be a gross deviation from what a reasonable person would be willing to do. Under these circumstances, the defendant’s action is reckless. As the code states, “the risk must be of such a nature and degree that disregard of it constitutes a gross deviation from the standard of conduct that a reasonable person would observe in the situation.” AS 11.81.900(a)(3)

Example of Recklessly

Let’s revisit Victor and Tanya. Suppose Victor and Tanya are driving back from their weekend camping trip with friends. As they are driving back Victor is shooting at passing highway signs. Although there is oncoming traffic on the highway, the oncoming cars are few and far between. As they pass an upcoming highway sign Victor shoots. The bullet ricochets off the sign and strikes a passing car, killing a passenger. A jury would likely find that Victor was acting recklessly in this situation. Victor’s knowledge and awareness of the risk of injury or death when shooting a gun with passing cars is probably substantial. A reasonable, law-abiding person would probably not take this action under these circumstances. Victor is likely guilty of manslaughter, a lower-level of criminal homicide. AS 11.41.120(a).

Criminal Negligence

The lowest level of criminal culpability is criminal negligence. The difference between reckless and criminally negligent culpability is the defendant’s lack of awareness. The criminally negligent defendant is faced with a substantial and unjustifiable risk, in which they are unaware, whereas the reckless defendant consciously disregards the unjustified risk. The criminally negligent defendant “fails to perceive” the risk. AS 11.81.900(a)(4).

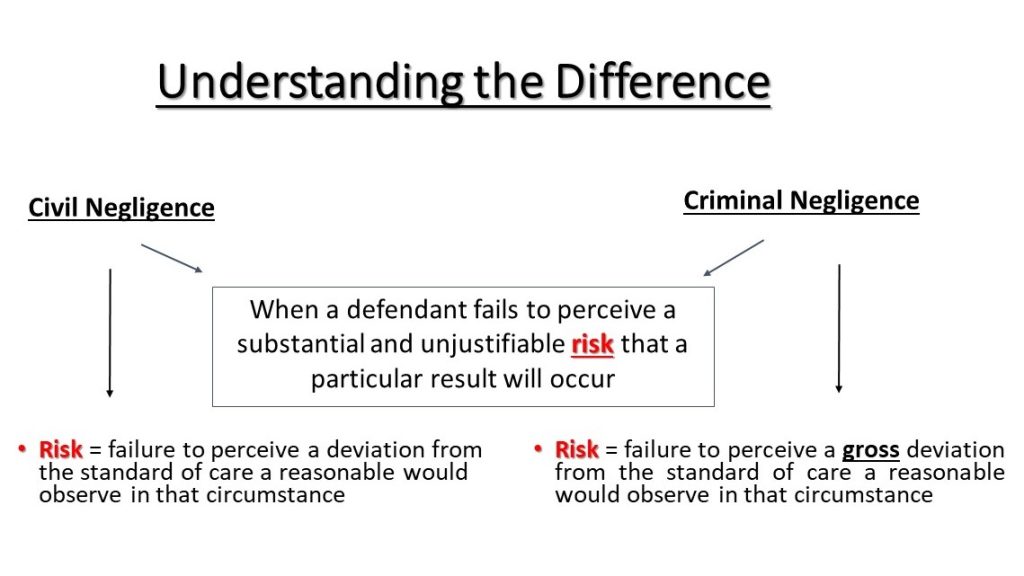

It is important to note that criminal negligence is different than civil negligence. See State v. Hazelwood, 946 P.2d 875, 878 (Alaska 1997). Criminal negligence requires a gross deviation from the standard of conduct a reasonable person would observe in a particular situation, whereas civil negligence requires a simple deviation from what a reasonable person would do in the situation. While this distinction may seem minor, remember, that criminal liability results in the potential deprivation of liberty. Civil liability simply results in the loss of money.

Figure 4.6 Understanding the Difference between Criminal and Civil Negligence

Example of Criminal Negligence

Let us discuss Victor and Tanya one last time. Assume that Victor is driving him and Tanya back home after their long, fun weekend of camping with friends. While driving, Victor continually sends text messages to a friend who missed the camping trip. While Victor is typing out a text message he drives off the roadway, causing the vehicle to roll into the ditch. Tanya dies in the accident. Under these facts, Victor may be unaware that texting and driving could result in him driving off the roadway and flipping the vehicle into the ditch. However, the trier of fact may determine that a “reasonable person” would be aware of the dangers of texting and driving, and such behavior could result in injury or death. This would be a finding that Victor acted criminally negligent in causing Tayna’s death. Under these circumstances, Victor is likely guilty of criminally negligent homicide. AS 11.41.130(a).

Elements of Different Culpable Mental States

Occasionally, a criminal statute will require different culpable mental statutes for different elements. In this scenario, the government must prove each mens rea beyond a reasonable doubt for each element.

Example of a Crime that Requires More Than One Criminal Intent

A person commits the crime of burglary in the first degree if the person “knowingly enters a dwelling with the intent to commit a crime therein.” AS 11.46.300. The statute contains three elements: (1) entering, (2) a dwelling, and (3) with the intent to commit a crime inside. The defendant must act “knowingly” with respect to entering a dwelling, but the defendant must act intentionally with respect to committing a crime while inside. This statute contains two different culpable mental states the prosecution must prove beyond a reasonable doubt to secure a conviction.

Willis v. State, 57 P.3d 688 (Alaska App. 2002)

The following case, Willis v. State, revisits the circumstances surrounding a parent’s duty to protect their child. How is a parent supposed to know what circumstances may lead to criminal liability? The answer involves the application of the relevant culpable mental states. As you read the case, pay attention to how the mens rea and the failure to act are intertwined.

57 P.3d 688

Court of Appeals of Alaska.

Kevin WILLIS and Barbara Nauska, Appellants,

v.

STATE of Alaska, Appellee.

Nos. A–7587, A–7778.

Oct. 25, 2002.

OPINION

MANNHEIMER, Judge.

Kevin Willis and Barbara Nauska were indicted for seriously injuring their two-month-old child. At six o’clock in the evening on July 17, 1997, Nauska brought the baby to the emergency room at Bartlett Regional Hospital in Juneau. The baby had a fractured skull and broken ribs.

According to medical testimony, these injuries were likely inflicted when someone grasped the infant by its chest and bashed its head against a wall or other hard object. Medical testimony also indicated that the baby sustained these injuries during the two hours preceding his arrival at the hospital. During most of this time, the infant was in the care of Willis and Nauska on their small houseboat. However, Willis and Nauska both claimed that they did not know how the baby was injured.

Following a police investigation, Willis and Nauska were indicted for second-degree assault. The State conceded that it could not prove which of them had assaulted the baby. However, the indictment was based on the theory that one of them had personally assaulted the infant while the other had knowingly stood by and allowed the assault to happen—thus violating their parental duty to protect the child and rendering them criminally liable for the resulting injuries.

At trial, Willis and Nauska asserted that their babysitter, Patrick Prewett, had assaulted the baby before they returned home that afternoon. The jury rejected this defense and convicted Willis and Nauska of second-degree assault[.] Both defendants now appeal their convictions and their resulting sentences.

[…]

The adequacy of the jury instructions concerning criminal responsibility based on a parent’s failure to act to protect their child

As explained above, the State could not identify either Willis or Nauska as the person who inflicted the baby’s injuries. The State’s theory of prosecution was that one of them assaulted their child while the other stood by and allowed the assault to occur. Because the case was litigated this way, the jurors had to be instructed concerning the circumstances under which a parent can be held criminally responsible for failing to protect their child.

Judge Weeks gave the jurors an instruction that combined both theories of criminal responsibility — i.e., responsibility based on personal commission of an assault, and responsibility for failing to act to prevent the assault:

A person commits the crime of assault in the second degree if, either by acting or by failing to act when he or she has a legal duty to act, that person recklessly causes serious physical injury to another person.

In order to establish the crime of assault in the second degree …, it is necessary for the state to prove beyond a reasonable doubt the following:

First, that the event in question occurred at or near Juneau and on or about July 17, 1997;

Second, that the defendant had a duty to protect [the child];

Third, that the defendant performed an act or failed to perform an act which resulted in serious physical injury to [the child];

Fourth, that the defendant acted recklessly.

[…]

On appeal, Willis and Nauska argue that the jury instruction on the elements of assault fails to correctly state the components of criminal responsibility based on dereliction of duty. As we explain below, the defendants are correct. However, … [g]iven the facts of this case and the way it was litigated, we conclude that this jury instruction did not constitute plain error [requiring reversal].

The two culpable mental states that must be proved when a parent is charged with homicide or assault for failing to protect their child

The elements of criminal responsibility based on dereliction of duty are set out in Michael v. State, 767 P.2d 193 (Alaska App.1988). The actus reus of the offense is the defendant’s failure to act when the defendant had a duty to act. The State must show that this failure to act was “knowing”.

More specifically, when a defendant is prosecuted for failing to act, the State must show that the defendant was aware of the circumstance that triggered the duty to act and that, being aware of this circumstance, the defendant chose to do nothing—i.e., “knowingly” refrained from acting. In the case of a parent prosecuted for assault or homicide for failing to protect their child, the State must prove that the parent knew of the need to take action to protect the child and knowingly refrained from taking action.

In addition to proving this actus reus, the State must additionally prove that the parent acted with the requisite culpable mental state regarding the result specified by the offense. (In a homicide prosecution, the prohibited result is death. In an assault prosecution, the prohibited result is either serious physical injury, physical injury, or apprehension of imminent injury.)

At first blush, it might seem superfluous to require proof of a separate culpable mental state regarding the possibility of the child’s injury—for, as we have just explained, the State must prove that the parent knew of the need to protect the child in order to establish that the parent’s failure to act was “knowing”. But children often engage in sports and other activities that hold some degree of physical peril. Even though a parent understands that their child might be injured while engaging in these activities, the parent’s knowing failure to intervene does not constitute a crime unless the government also proves that the parent acted (or, more precisely, failed to act) with a culpable mental state regarding the potential injury—a culpable mental state that will vary according to the crime charged.

For example, even though a child might conceivably suffer serious physical injury while skiing or while driving a motor vehicle, the child’s parent could not be convicted of second-degree assault under AS 11.41.210(a)(2) (recklessly causing serious physical injury) for failing to take protective action unless the government proved that the parent acted “recklessly” with regard to this result—i.e., proved that the parent was “aware of and consciously disregard [ed] a substantial and unjustifiable risk” that serious physical injury would occur if the parent failed to intervene. See AS 11.81.900(a)(3), the statutory definition of “recklessly”.

Under this statutory definition, the government would have to show that the risk of serious physical injury was “of such a nature and degree that [the parent’s] disregard of it constitute[d] a gross deviation from the standard of conduct that a reasonable person would observe in the situation”. This, in a nutshell, is the difference between letting a toddler play with a firearm and letting an adolescent go on a hunting trip.

[…]

Why we conclude that Judge Weeks did not commit plain error when he gave this jury instruction

We have just explained why, when a defendant is prosecuted for second-degree assault based on dereliction of their parental duty, the government’s burden to prove that the defendant knowingly failed to act is distinct from its burden to prove that the defendant was reckless with respect to the possibility that their failure to act might result in serious physical injury. Nevertheless, it is often true that the same facts will prove both elements.

For example, if a parent does nothing even though they are aware that their spouse is assaulting their infant child, this fact will tend to prove both the defendant’s knowing failure to act and the defendant’s recklessness concerning the possibility of serious physical injury. That was the case in Michael, and it was also the State’s theory of prosecution against Willis and Nauska.

The State presented evidence that Willis’s and Nauska’s baby sustained serious physical injury in the late afternoon of July 17, 1997, that this injury was the result of an assault rather than an accident, and that Willis and Nauska were alone with the baby on a small houseboat when the injury occurred. The State alleged that one of the two defendants violently assaulted the baby while the other one looked on and did not intervene.

Faced with this theory of prosecution, Willis and Nauska conceivably might have pursued litigation strategies that highlighted the need to instruct the jury on the element of a knowing failure to act. For instance, either defendant might have contended that they left the houseboat for some reason and that their spouse was alone with the baby when the baby was injured. Alternatively, either defendant might have contended that, although they were present on the houseboat when the baby was injured, they had fallen asleep from fatigue and/or intoxication and thus they were unaware that the baby was being assaulted by their spouse. Or either defendant might have asserted that their spouse assaulted the baby but that the assault occurred in an instant, giving the defendant no time to intervene or do anything other than rush the baby to the hospital.

Likewise, the defendants might have pursued a litigation strategy that highlighted the distinction between a knowing failure to act and recklessness concerning the possibility of serious physical injury. For instance, one of the defendants might have asserted that, even though they knowingly failed to prevent their spouse from assaulting the child, they had no reason to believe that the assault would be severe enough to inflict serious physical injury on the baby.

But Willis and Nauska did not pursue such litigation strategies. Instead, from beginning to end, Willis and Nauska jointly asserted that no harm had befallen the baby while he was in their presence. Both defendants argued that Prewett [the babysitter] was the culprit—that he assaulted the baby before Willis and Nauska returned to the houseboat in the late afternoon.

Given the way this case was litigated, the jury’s crucial task was to determine who injured the baby. If it was either Willis or Nauska, this meant that the remaining spouse witnessed the assault and did nothing. Under these circumstances, the two culpable mental states effectively coalesced. Judge Weeks’s jury instruction told the jurors that the State was obliged to prove that the non-assaulting parent acted recklessly—that the non-assaulting parent was aware of and consciously disregarded a substantial and unjustifiable possibility that their spouse would inflict serious physical injury on the baby. Given the defense strategy adopted by Willis and Nauska, such a finding was tantamount to a finding that the non-assaulting parent knowingly failed to protect the baby.

[…]

Conclusion

The judgements of the superior court are AFFIRMED.

Strict Liability

There is one big exception to the rule that every criminal law violation includes a culpable mental state – strict liability. Strict liability offenses have no intent element. AS 11.81.600(b). Strict liability offenses hold a person criminally responsible for their conduct regardless of their intent. Generally speaking, strict liability offenses are limited to regulatory and public welfare crimes. With a strict liability crime, the prosecution has to prove only the criminal act, causation, and harm, depending on the elements of the offense.

Example of a Strict Liability Offense

The Glenn Highway has a posted speed limit of 65 mph. If Susie is stopped by Anchorage police for driving 75 mph, she is subject to a traffic ticket regardless of her intent. Thus, “but officer, I didn’t know I was speeding” is not a valid defense. This is a strict liability offense. Susie’s knowledge of the nature of the act is irrelevant. The prosecution only needs to prove the criminal act to convict Susie because this statute is strict liability.

Kinney v. State, 927 P.2d 1289 (Alaska App. 1996)

Does the government have to prove a person knew their conduct was illegal? This is a different situation than strict liability discussed above. In the example above, Susie claimed she did not know she was speeding. But what if the defendant does not know their conduct was illegal? Generally, ignorance of the law is no defense. But this rule is not absolute. In the following case, Kinney v. State, the court faced a defendant claiming the government was required to prove that he knew his conduct was illegal. As you read Kinney notice how several of the principles discussed throughout the text impact the court’s reasoning.

927 P.2d 1289

Court of Appeals of Alaska.

Dean C. KINNEY, Appellant,

v.

STATE of Alaska, Appellee.

No. A–5812.

Nov. 29, 1996.

OPINION

MANNHEIMER, Judge.

Dean C. Kinney was convicted of arranging a sale of liquor in a local-option community—a community where, by local vote, the sale of liquor was banned. Kinney argues that his conviction is invalid because the jury never determined whether Kinney knew that he was breaking the law when he arranged the sale of the liquor. We hold that the State was not required to prove that Kinney knew he was breaking the law.

[…]

Facts of the Case

During January and February of 1994, the state troopers conducted an investigation of bootlegging in Bethel. One of their undercover informants was Rick Wilson. Wilson had arranged to purchase liquor from A.A., a suspected bootlegger, on February 1st, but when Wilson arrived for the transaction, A.A. demurred. Instead, A.A. offered to introduce Wilson to another bootlegger. He then took Wilson to the Hammer Manor Apartments, where he introduced him to the manager, Dean Kinney. Kinney offered to sell liquor to Wilson, but Wilson declined.

The next day, Wilson returned to the Hammer Manor Apartments and attempted to purchase alcohol from Kinney. This time, Kinney told Wilson that he would have to make a telephone call first. Kinney made the call and, soon thereafter, someone knocked at Kinney’s door. Kinney went out to speak to the person at his door; when Kinney came back in, he was carrying a bottle of vodka. Kinney gave the bottle to Wilson, and Wilson gave Kinney $50.00 in pre-recorded buy money. Upon leaving Kinney’s apartment, Wilson took the bottle to his trooper supervisor and reported this transaction. Based on this sale, the troopers obtained a warrant to record ensuing transactions between Wilson and Kinney.

On February 4th, Wilson returned to Kinney’s apartment and asked if he could buy another bottle of liquor. This second transaction occurred in much the same way as the first: Kinney made a telephone call, a bottle was delivered outside Kinney’s apartment, and Kinney sold the bottle to Wilson for $50.00. During the negotiation of this sale, Wilson asked Kinney if he could “give [him] a break on the price”. Kinney replied that he was only making a profit of $5.00 on each sale and he therefore could not lower the price.

On February 18th, Wilson made a third purchase from Kinney. Wilson went to Kinney’s apartment and told Kinney that he wanted to make a purchase. This time, Kinney asked Wilson how many bottles he wished to purchase; Wilson replied that he wanted just one. Again, Wilson offered Kinney $50.00, but this time Kinney told Wilson to return one hour later. Both men left Kinney’s apartment. Approximately one hour later, Kinney returned to the apartment, and Wilson arrived soon thereafter. Kinney had a bottle of liquor for Wilson upon his return. During this third transaction, Wilson again asked Kinney to give him a break on the price, but Kinney again refused, adding that he “wasn’t making anything”.

Kinney was ultimately indicted on three counts of felony bootlegging[.] Following a jury trial in the Bethel superior court, Kinney was convicted for the second and third sales (the ones that had been recorded).

In a prosecution for bootlegging, must the government prove that the defendant knew his conduct was illegal?

At trial, Kinney asked the judge to instruct the jury that Kinney could not be convicted unless the government proved that he was “aware that his conduct was of an illegal nature”. The trial judge declined to give this instruction. On appeal, Kinney argues that his proposed instruction was constitutionally required.

Kinney’s argument hinges on language taken from Hentzner v. State, 613 P.2d 821 (Alaska 1980), a case in which the supreme court interpreted the culpable mental state required for the crime of selling unregistered securities. Hentzner was prosecuted under [a statute], which provide[d] criminal penalties for anyone who “willfully” violates the Securities Act. The supreme court had to decide what “willfully” meant.

To interpret this statute, the supreme court relied on the principle that a person may not be convicted of a crime (with the exception of minor violations and public welfare offenses) unless the government proves that the defendant acted with “criminal intent”, in the broad sense of “a culpable mental state”. Referring to this basic requirement of criminal intent, the court said:

Where the crime involved may be said to be malum in se, that is, one which reasoning members of society regard as condemnable, awareness of the commission of the act necessarily carries with it an awareness of wrongdoing. In such a case[,] the requirement of criminal intent is met upon proof of conscious action, and it would be entirely acceptable to define the word “willfully” to mean no more than consciousness of the conduct in question. … However, where the conduct charged is malum prohibitum[,] there is no broad societal concurrence that it is inherently bad. Consciousness on the part of the actor that he is doing the act does not carry with it an implication that he is aware that what he is doing is wrong. In such cases, more than mere conscious action is required to satisfy the criminal intent requirement….

The crime of offering to sell or selling unregistered securities is malum prohibitum, not malum in se. Thus, criminal intent in the sense of consciousness of wrongdoing should be regarded as a separate element of the offense[.]

Hentzner, 613 P.2d at 826.

Kinney contends that the crime of bootlegging, like the crime of selling unregistered securities, is malum prohibitum. He therefore argues that, like the defendant in Hentzner, he too could not be convicted unless the State proved that he acted with “consciousness of wrongdoing”. According to Kinney, this means proving that he understood that his conduct violated the law.

The distinction between crimes that are “mala prohibita” and those that are “mala in se” has not only shaped but, to a certain extent, also bedeviled the law. Basically, a crime is termed “malum prohibitum” if it is “not inherently evil [but is] wrong only because prohibited by the legislature”. A crime is “malum in se” if it is “wrong in [itself], inherently evil”.

However, as [legal scholars] point out, this terminology has never been precise. Generally, common-law crimes are called “mala in se” and statutory crimes are called “mala prohibita”, but courts also say that a crime is “malum in se” if it involves “moral turpitude”. These criteria sometimes point in different directions. For instance, the offenses of embezzlement and obtaining money by false pretenses are statutory expansions of the common-law crime of larceny, yet few would dispute their classification as crimes of moral turpitude.

[…]

Given criteria like these, there is little wonder that courts reach differing answers when asked to classify the same offense. For instance, the crimes of driving while intoxicated and possession of drugs have been classified by some courts as mala in se, while other courts have found them to be mala prohibita. [Legal scholars] conclude that “[t]he difficulty of classifying particular crimes as mala in se or mala prohibita suggests … that the classification should be abandoned[.]”

As an intermediate appellate court, we are loath to abandon a classification that our supreme court has expressly relied on. Rather, our task should be to interpret how that classification applies to the case before us.

Hentzner declares that a crime is malum prohibitum if “there is no broad societal concurrence that [the proscribed conduct] is inherently bad”. One could argue that even though unlicensed sale of liquor is normally malum prohibitum, sale in a local-option community is malum in se. If a person sells liquor in a community where sale is legal but restricted to certain license-holders, then the crime is simply a violation of laws regulating commercial transactions. But if a community has seen the need to prohibit all sales of alcohol, then there may be “broad societal concurrence” that the act of selling alcohol is condemnable.

Despite this potential argument, we will assume for purposes of deciding Kinney’s appeal that all laws prohibiting the sale or distribution of alcohol create mala prohibita crimes. Nevertheless, we reject Kinney’s assertion that, under Hentzner, the State had to prove that Kinney understood the law and knew that he was breaking it.

As noted above, Hentzner involved a prosecution for the crime of offering securities that had not been registered with the Department of Commerce and Economic Development. [In Hentzer], the defendant, who was attempting to raise money for a gold-mining venture, offered to sell his to-be-mined gold for the price of $80.00 an ounce (substantially below market value) to anyone who would pay the purchase price immediately. That is, Hentzner was asking people to give him money in exchange for his promise that, in several months, they would be repaid in gold at the extremely favorable rate of one ounce for every $80.00 they advanced him.

The State alleged that Hentzner’s fund-raising effort constituted the offering of a “security” (more specifically, an “investment contract”). The State’s theory was that, by offering to sell gold that had not yet been mined, Hentzner was in effect asking people to invest money upon the promise that they would share in future gold-mining profits to be derived from Hentzner’s entrepreneurial or managerial efforts.

Hentzner represented a collision between the practice of “grubstaking”, a traditional way for western miners to raise capital, and Alaska’s securities act—in particular, the labyrinth of definitions and exemptions codified in [Alaska securities laws]. Under Alaska’s securities laws, the request for a grubstake is the offer of a “security”, and a miner who wishes to ask for a grubstake must register this offering.

The definition of a security and the rules governing registration are not matters of common knowledge. Thus, the supreme court faced a situation in which a miner who pursued a traditional capital-raising practice, who engaged in no misrepresentation, and who (at least arguably) acted reasonably in failing to discover the need to register his fund-raising effort, could nevertheless face felony conviction for his failure to register the grubstake offer with the Department of Commerce and Economic Development. Given this context, it is hardly surprising that the supreme court ruled that “willfully” failing to register the grubstake offer required proof of something more than mere failure to register.

Kinney interprets Hentzner as saying that this “something more” must be proof that the defendant understood that his conduct violated the law.

[…]

[However, the] language from Hentzner indicates that the supreme court did not think it had imposed the mens rea requirement that Kinney argues for in the present appeal—the purported requirement that the government prove that the defendant acted with “knowledge of the law” and awareness “that he was breaking it”.

…

[The supreme court’s] “primary concern was to avoid application of strict liability in cases where the accused could be subjected to severe criminal penalties”. Hentzner was charged with a felony, not for offering his investment scheme, but for failing to register it. Thus, Hentzner’s crime was one of omission. “The gist of [Hentzner’s] crime was … the defendant’s failure to perform an act required by law—registering the securities before offering them to the public.”

[W]hen a crime is defined in terms of a failure to act, “the prevailing view is that one may not be held liable if one does not know the facts indicating a duty to act”. Thus, [under the law] if a person reasonably fails to perceive that his business activities fall within the securities laws, so that his failure to register is an act of reasonable inadvertence, then that person should not be guilty of a felony for failing to register.

Kinney’s case is substantially different. Kinney was charged with selling alcohol; his crime was one of commission, not omission. Kinney’s sales of alcohol did not arise through inadvertence or neglect. Moreover, it is common knowledge in our society that one is not permitted to sell alcohol without a license, and it is common knowledge in Alaska that various localities have voted themselves dry. Under these circumstances,

[w]hat is essential is not an awareness that a given conduct is a “wrongdoing” in the sense that it is proscribed by law, but rather, an awareness that one is committing the specific acts which are defined by law as a “wrongdoing”. It is … no defense that one was not aware his acts were wrong in the sense that they were proscribed by law. So long as one acts intentionally, with cognizance of his behavior, he acts with the requisite awareness of wrongdoing. In the words of Justice Holmes:

If a man intentionally adopts certain conduct in certain circumstances known to him, and that conduct is forbidden by the law under those circumstances, he intentionally breaks the law in the only sense in which the law ever considers intent.

Ellis v. United States, 206 U.S. 246, 257 (1907).

It was not necessary for the State to prove that Kinney was aware of the bootlegging law and knew that his conduct violated that law. We therefore uphold the trial judge’s refusal to give Kinney’s proposed jury instruction.

[…]

Conclusion

The judgement of the superior court is AFFIRMED.

Concurrence of the Act and Intent

There must be a “joint operation” between the culpable mental state and prohibited conduct. This ‘joint operation’ is referred to as concurrence. While concurrence almost always occurs at the same moment, they need not be simultaneous. Instead, the two elements must causally relate – that is, the actus reus must be attributable to the mens rea. See Jackson v. State, 85 P.3d 1042 (Alaska App. 2004). This means that an innocent mistake is generally not a crime, or is an evil mind without action. Exceptions exist of course, but the general rule is that there must be a marriage between the voluntary act and the guilty mind.

Example of a Situation Lacking Concurrence

Susan decides she wants to kill her husband using a handgun. As Susan is driving to the local gun shop to purchase the handgun, her husband is distracted and steps in front of her car. Susan slams on the brakes as a reflex, but unfortunately, she is unable to avoid striking and killing her husband. Susan cannot be prosecuted for criminal homicide in this case. Although Susan had formulated the intent to kill, the intent to kill did not exist at the moment she committed the criminal act of hitting her husband with her vehicle. Susan was trying to avoid hitting her husband at the moment he was killed. Thus this case lacks concurrence of act and intent, and Susan is not guilty of criminal homicide.