Riot, Disorderly Conduct, and Harassment

Crimes against public order include offenses that affect a community’s positive function, like public nuisances, group violence, and vice crimes. These crimes are often based on moral or value judgments. In most situations, these crimes are classified as mala prohibita offenses. More than most crimes, these crimes require a balance between citizens’ civil liberties and the right of the community to be free from vagrancy, harassment, and fear.

In this chapter, we explore disorderly conduct, riot, and harassment. Disorderly conduct and harassment are recognized as “catch-all” type criminal statutes – they both criminalize a vast range of offensive and disruptive, albeit minor, conduct.

Disorderly Conduct

Disorderly conduct criminalizes conduct that negatively impacts a community’s “quality of life”. Disorderly conduct is a low-level offense and focuses on relatively minor acts of criminality. Its enforcement, however, is necessary to preserve citizens’ ability to live, work, and travel in safety and comfort. Modern disorderly conduct statutes punish behaviors that are violent, abusive, indecent, profane, boisterous, unreasonably loud, or otherwise disturb the public. Criminal laws addressing this sort of behavior are not new: at common law, breach of peace criminalized activities that disturbed the tranquility of the citizenry. Disorderly conduct has its origins in the common law crime of affray: “[a] noisy fight in a public place … to the terror of onlookers.” See Affray Black’s Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019). Affray “comes from the same source as the word ‘afraid,’ and [its] tendency to alarm the community is the very essence of this offense.” Rollin M. Perkins & Ronald N. Boyce, Criminal Law 479 (3d ed. 1982).

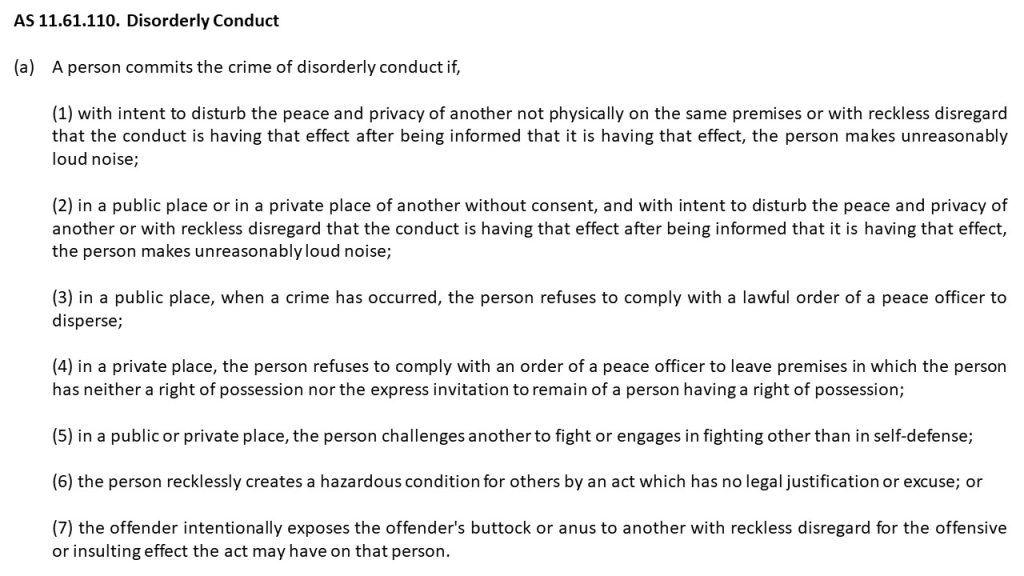

The modern definition is broader than a noisy fight in public. Alaska’s disorderly conduct statute encompasses a wide range of conduct that disturbs the peace and tranquility of our communities. AS 11.61.110(a).

Figure 9.1 Alaska Criminal Code – Disorderly Conduct

There are seven different ways of committing disorderly conduct. The first two, subparagraphs (1) and (2), prohibit the making of an unreasonably loud noise. “Unreasonably loud” is not a fixed term. It is dependent on the nature of the defendant’s conduct and the circumstances surrounding the conduct – including the location and time of day. AS 11.61.110(b). The noise must disturb a person’s peace and privacy. The legislative commentary notes that this phrase is intended to take into account the circumstances of the noisemaking. The critical question is whether the defendant’s conduct in making the noise constitutes a gross deviation from “the standard of conduct that a reasonable person would observe in the same situation.” AS 11.61.110(b).

For example, signing the national anthem at the top of your lungs using a bullhorn outside a hospital at 2:00 a.m. would likely constitute an unreasonably loud noise, but doing so in a ballpark at noon would not. Likewise, a person attending a sporting event would have a lower expectation of freedom from disturbance than a person attending a poetry reading. A police officer, conducting a bar check, could not claim to be disturbed by noise associated with a bar.

The definition of noise specifically excludes speech that is constitutionally protected. AS 11.61.110(b). Although the statute does not define constitutionally protected speech, it includes protected speech discussed in Chapter 3. The exclusion of protected speech ensures that the statute comports with the First Amendment. Unprotected speech, on the other hand, is included within the statute. Fighting words, obscene speech, and hate speech are not protected forms of speech and appropriately form the basis of a disorderly conduct conviction.

The difference between subparagraphs (a)(1) and (a)(2) is the location of the noisemaking. Subparagraph (a)(1) prohibits noisemaking that disturbs another person not on the same premises, while subparagraph (a)(2) prohibits noisemaking in a public place or on private property. For example, if an apartment dweller disturbs his neighbor’s peace by listening to his music at an unreasonably loud level at 4:00 am, the apartment dweller is guilty of disorderly conduct under (a)(1). On the other hand, if a group of teenagers plays loud music in a neighborhood park at 4:00 a.m. and disturbs the surrounding homeowners, they are guilty of disorderly conduct under (a)(2).

The next two subsections authorize police to arrest a person for failing to obey a lawful police order. First, refusing to disperse from a public place upon the lawful order of a peace officer when a crime has occurred may be prosecuted under (a)(3). AS 11.61.110(a)(3). The citizen’s refusal to disperse must substantially impede the officer’s ability to effectuate an arrest, investigation, or otherwise endanger public safety. See State v. Martin, 532 P.2d 316 (Alaska 1975). Likewise, refusing to comply with a police officer’s order to leave a private place (a place not open to the public) when the suspect has neither the right of possession nor the express invitation to remain is prohibited under (a)(4). AS 11.61.110(a)(4).

Disorderly conduct includes three final prohibitions. First, the statute prohibits the reckless creation of “a hazardous condition for others by an act which has no legal justification or excuse.” AS 11.61.100(a)(6). This criminalizes creating a dangerous situation without cause, like shouting “fire!” in a crowded movie theater. Such conduct gratuitously risks innocent people getting hurt. Second, the crime of disorderly conduct prohibits intentionally exposing one’s buttock or anus with reckless disregard for the offensive or insulting effect it may have on another person. This subsection criminalizes age-old high school activity of mooning. AS 11.61.100(a)(7).

Finally, disorderly conduct prohibits challenging another person to a fight, or engaging in fighting other than self-defense. AS 11.61.110(a)(5). Fighting, unlike assault, requires a mutuality of intention – that is, a voluntary participation to engage in physical combat. In the following case, Dawson v. State, the court explains the difference between misdemeanor assault (i.e., recklessly causing physical injury to another person) and disorderly conduct (i.e., engaging in fighting other than self-defense). As you read the next opinion, notice how the court defines “fighting” using the common law crime of “affray.”

Dawson v. State, 264 P.3d 851 (Alaska App. 2011)

264 P.3d 851

Court of Appeals of Alaska.

Ginnie DAWSON, Appellant,

v.

STATE of Alaska, Appellee.

No. A–10137.

Oct. 21, 2011.

OPINION

MANNHEIMER, Judge.

This case requires us to construe one clause of our disorderly conduct statute, AS 11.61.110—specifically, subsection (a)(5) of the statute, which declares that a person commits disorderly conduct if the person “engages in fighting other than in self-defense”. The precise issue is whether the phrase “engages in fighting” encompasses all instances where one person strikes another—or whether, instead, this phrase is limited to situations where two or more people share a mutual intent to trade blows (or at least attempt to trade blows).

For the reasons explained in this opinion, we conclude that, for purposes of this subsection of the disorderly conduct statute, “fighting” requires a mutuality of intention, and therefore this subsection of the statute does not cover all situations where one person strikes another.

Underlying facts

The Appellant in this case, Ginnie Dawson, was charged with fourth-degree assault under AS 11.41.220(a)(1) for hitting her domestic partner, Patrick Meyer, with her fists and throwing a baking pan at him. To prove this assault charge, the State had to establish that Dawson “recklessly cause[d] physical injury to [Meyer]”.

As used in our criminal code, the term “physical injury” means “physical pain or an impairment of physical condition”. The State alleged that Dawson’s acts of striking Meyer with her fists and with the baking pan constituted fourth-degree assault because this conduct caused Meyer to suffer physical pain.

At trial, Dawson conceded that she struck Meyer, but she contended that she had not caused him physical pain. Meyer took the stand and agreed that he had not suffered pain (other than emotional pain) during the attack.

Based on this testimony, Dawson’s attorney asked the trial judge to instruct the jury on the lesser offense of disorderly conduct as defined in AS 11.61.110(a)(5)—“engag[ing] in fighting other than in self-defense”. The defense attorney argued that if the jury believed Meyer’s testimony that he had not suffered pain, then the State would have proved only that Dawson fought with Meyer—and, thus, disorderly conduct under subsection (a)(5) would be the proper verdict.

The trial judge refused to instruct the jury on disorderly conduct because (1) the judge concluded that “fighting” meant a mutual physical struggle between two or more people, and (2) there was no evidence that Meyer and Dawson engaged in mutual struggle—i.e., no evidence that Meyer intended to fight Dawson, or that he responded with physical force to Dawson’s blows.

The jury convicted Dawson of fourth-degree assault, and Dawson now claims that the trial judge committed error by refusing to instruct the jury on disorderly conduct as a potential lesser included offense.

This Court’s decision in Hedgers v. State

As we have just explained, the primary issue raised in this appeal is whether the phrase “engages in fighting” (as used in subsection (a)(5) of the disorderly conduct statute) includes all situations where one person strikes another, even though there is no mutual combat—i.e., even though the second person does not wish to engage in a physical struggle, and does not respond with force. This Court has already directly addressed and answered this question in an unpublished opinion: Hedgers v. State, Alaska App. Memorandum Opinion No. 4056 (June 2, 1999), 1999 WL 349062.

The defendant in Hedgers was convicted of disorderly conduct under subsection (a)(5) of AS 11.61.110—i.e., for engaging in fighting other than in self-defense—based on evidence that, during a verbal dispute with another woman, she used her knee to kick this other woman in the leg. Hedgers, slip opinion at 1–2, 1999 WL 349062 at *1.

On appeal, Hedgers argued that she was wrongly convicted because “fighting” required mutual combat. This Court rejected Hedgers’s argument. We held that the term “fighting” encompassed any “physical struggle”—more specifically, that it included “those fights that are one-sided due to choice, surprise by the aggressor, or simply the superior ability of a participant.” Hedgers, slip opinion at 2–3, 1999 WL 349062 at *2.

Thus, in Hedgers, this Court rejected the interpretation of “fighting” that Dawson’s trial judge employed in the present case. Instead, Hedgers adopted the interpretation that Dawson proposes: the interpretation that “fighting” includes all instances where one person knowingly strikes another, even though the other person does not wish to fight and does not respond with force.

Given the underlying facts of Dawson’s case, and given the fact that the primary dispute between the parties at Dawson’s trial was whether Meyer suffered physical pain as a result of Dawson’s striking him, it would appear that, under our decision in Hedgers, Dawson was indeed entitled to a jury instruction on the lesser offense of disorderly conduct.

However, for the reasons explained in this opinion, we conclude that we were mistaken in Hedgers when we declared that “fighting” does not require any degree of mutuality. We now hold that the phrase “engages in fighting” encompasses only those situations where the participants share a mutual purpose or understanding that they will trade blows or attempt to trade blows.

The origins of subsection (a)(5) of our disorderly conduct statute

The common law provided criminal penalties for direct assaults or batteries upon another person, but it also provided penalties for people who breached the public peace with violent, tumultuous, or otherwise disorderly conduct, even when that conduct did not constitute a punishable assault or battery.

If a group of people assembled for the purpose of engaging in violent or tumultuous behavior (and then engaged in that behavior), they were guilty of “riot”. This offense (as generally defined) consisted of “planned and deliberate violent or tumultuous behavior involving a confederation of three or more persons”. Most American jurisdictions have enacted statutory versions of the offense of riot.

A lesser common-law crime—“affray”—applied to breaches of the peace by people who had come together in a public place by chance or otherwise innocently, and then a quarrel arose which prompted them to engage in violent or tumultuous behavior. In such circumstances, the participants “[were] not guilty of riot, but of sudden affray only”, because “[the] breach of the peace happened unexpectedly without any previous intention concerning it.” Affray was defined as “a mutual fight in a public place to the terror or alarm of [other] people”.

To constitute an “affray”, the parties’ intention or willingness to fight had to be mutual. If one person unlawfully attacked another, and the other person used force in an effort to defend himself, the instigator was guilty of assault and battery, while the other participant was entirely innocent of crime. In such circumstances, there was no affray.

Moreover, with respect to both of these offenses—riot and affray—the gravamen of the offense was not any injury to persons or property that might ensue, but rather the present breach of the public peace and the attendant risk of terror or alarm that the violent or tumultuous behavior might cause.

As is true with the offense of riot, most American jurisdictions have codified the common-law crime of affray. Sometimes the codified crime is called “affray”, but often state legislatures insert this offense into one of the provisions of their disorderly conduct statutes. The Alaska territorial legislature took this latter approach: they enacted a disorderly conduct statute in 1935 which, among other things, prohibited “tumultuous conduct in any public place or private house to the disturbance or annoyance of any person”. 1949 Compiled Laws of Alaska, § 65–10–3.

Following statehood, this definition was carried forward in former AS 11.45.030, a statute entitled “Disorderly conduct and disturbance of the peace”. As originally enacted (that is, before the 1973 amendments that we describe later), subsection (2) of this statute provided that a person committed disorderly conduct if they:

[were] guilty of tumultuous conduct in a public place or private house to the disturbance or annoyance of another, or [were] otherwise guilty of disorderly conduct to the disturbance or annoyance of another[.]

We note that this statute was broader in scope than the common-law crime of affray, in that it applied to tumultuous or disorderly conduct not only in public places but also in private houses.

During the early days of Alaska statehood, various city governments also enacted disorderly conduct ordinances that covered the type of conduct which would have been an “affray” at common law. For example, the Anchorage disorderly conduct ordinance (in its 1970 version) declared, in pertinent part, that it was unlawful “for any person[,] with purpose and intent[,] to cause public inconvenience, annoyance or alarm, or recklessly create a risk [of these things] by … [e]ngaging in fighting or threatening, or in violent or tumultuous behavior”.

But in 1972, in Marks v. Anchorage, 500 P.2d 644 (Alaska 1972), the Alaska Supreme Court ruled that this Anchorage ordinance was unconstitutional—and the supreme court’s decision led to a complete revision of the state disorderly conduct statute.

In Marks, the supreme court concluded that the Anchorage disorderly conduct ordinance was unconstitutionally vague both in its prefatory language (“cause public inconvenience [or] annoyance”) and in its use of the phrase “violent or tumultuous behavior”. Id., 500 P.2d at 645, 652–53. Although, technically speaking, the Marks decision dealt only with the Anchorage ordinance, the Alaska Legislature could see the writing on the wall, so they completely rewrote the state disorderly conduct statute the following year (1973). (The Alaska Supreme Court indeed struck down the pre–1973 version of the state statute in Poole v. State, 524 P.2d 286, 289 (Alaska 1974).)

In the 1973 revision of AS 11.45.030, the phrases “tumultuous conduct in a public place or private house to the disturbance or annoyance of another” and “disorderly conduct to the disturbance or annoyance of another” were replaced by a series of more specific provisions. For purposes of the present discussion, the pertinent clause of this revised, post–1973 version of the disorderly conduct statute is subsection (a)(3). This subsection declared that a person was guilty of disorderly conduct if “in a public or private place” [the person] “challenge[d] another to fight, or engage[d] in fighting other than in self-defense[.]”

In other words, subsection (a)(3) of the post–1973 disorderly conduct statute is the source of the language that is now found in subsection (a)(5) of our current disorderly conduct statute, AS 11.61.110—the statute that we must construe in this appeal.

The treatment of fighting and other breaches of the peace under Alaska’s current criminal code

The Alaska criminal code was completely rewritten in the late 1970s. The drafters of the new criminal code proposed a series of three statutes (all of them contained in Title 11, chapter 61) to cover the general subject of conduct that threatens the peace. See Alaska Criminal Code Revision, Tentative Draft, Part 5 (1978), pp. 78–89. These three statutes were later enacted as AS 11.61.100, AS 11.61.110, and AS 11.61.120.

AS 11.61.100 defines the felony of “riot”. Under this statute, a person commits riot “if, while participating with five or more others, the person engages in tumultuous and violent conduct in a public place and thereby causes, or creates a substantial risk of causing, damage to property or physical injury to a person.”

Moving down in degree of seriousness, AS 11.61.120 defines the misdemeanor of harassment. The pertinent portions of this statute are subsections (a)(1) and (a)(5), which declare that a person commits harassment if the person “insults, taunts, or challenges another person in a manner likely to provoke an immediate violent response”, or if the person “subjects another person to offensive physical contact”.

The first clause of the statute is a codification of the common law. At common law, a person was chargeable with a breach of the peace if the person directed opprobrious or abusive language toward another person with the intent to incite the other person to violence, or under circumstances where the language was likely to provoke immediate violence. The second clause of the statute was intended to cover minor shoves, slaps, or kicks that would not qualify as assaults under AS 11.41.200–230 because they do not inflict “physical injury”. This latter clause was also intended to cover touchings of a sexual nature that would not qualify as sexual assaults or sexual abuse under AS 11.41.410–440.

Finally, AS 11.61.110 defines the class B misdemeanor of “disorderly conduct”. As we have already noted, the pertinent portion of this statute (for purposes of the present appeal) is subsection (a)(5), which declares that a person commits disorderly conduct if, “in a public or private place, the person challenges another to fight or engages in fighting other than in self-defense”. This is simply a reiteration of subsection (a)(3) of the prior statute (as it was rewritten in 1973).

Although disorderly conduct is designated a class B misdemeanor (a class of offense which normally carries a maximum penalty of 90 days’ imprisonment), the legislature has specified that the sentence of imprisonment for disorderly conduct can be no more than 10 days. See AS 11.61.110(c).

Why we conclude that the phrase “engages in fighting other than in self-defense” requires proof of a mutual intention or willingness among the participants

We now return to the issue of statutory interpretation presented in Dawson’s case. Under AS 11.61.110(a)(5), a person commits disorderly conduct if the person “challenges another to fight or engages in fighting other than in self-defense”. The question is whether the phrase “engages in fighting” encompasses any instance where one person strikes another—or whether this phrase applies only to situations where the parties share a mutual intention or understanding that they will exchange blows, or at least attempt to exchange blows.

As we have explained, this statutory language was formulated in 1973, when the legislature rewrote the disorderly conduct statute in response to the supreme court’s decision in Marks v. Anchorage. At that time (i.e., before the enactment of our current criminal code), Alaska law contained a separate statute—former AS 11.15.230—that punished all acts of assault and battery, including all instances where one person unlawfully struck another person.

Former AS 11.15.230 declared that any person who unlawfully assaulted, threatened, or struck another person was guilty of a misdemeanor and subject to imprisonment for up to six months. As our supreme court noted in Rivett v. State, 578 P.2d 946, 948 (Alaska 1978), a person could commit assault and battery under this former statute by throwing “a simple punch [to] the nose, by means of a bare fist”.

Because the crime of “assault and battery” as defined in former AS 11.15.230 already covered any act of unlawfully striking another person, the legislature must have intended to deal with a different social problem when, in 1973, they rewrote the disorderly conduct statute and included a subsection that prohibited “fighting other than in self-defense”.

We believe that the legislature’s intention is explained by the statutory history that we recited in the preceding section of this opinion.

As we have already described, prior to the 1973 amendments prompted by Marks v. Anchorage, Alaska’s disorderly conduct statute prohibited all “tumultuous conduct in a public place or private house to the disturbance or annoyance of another”. This prohibition on “tumultuous conduct” was derived from the common-law crime of affray, which covered any sudden or unplanned breach of the peace by fighting or other tumultuous behavior.

But in Marks, the Alaska Supreme Court struck down a similarly worded municipal disorderly conduct ordinance—in part, because it employed the phrase “violent or tumultuous behavior”. Id., 500 P.2d at 645, 652–53. This prompted the Alaska Legislature to revise the state disorderly conduct statute by deleting the phrase “tumultuous conduct” and substituting more concrete definitions of the prohibited conduct. Among these more concrete definitions were “challeng[ing] another to fight” and “engag[ing] in fighting other than in self-defense”.

Given the fact that this prohibition on “fighting” has its origins in the common-law offense of affray (which required a mutual intent or willingness to fight), and given the fact that a separate existing statute prohibited all batteries, one can infer that the legislature was describing situations of mutual fighting, rather than all situations where one person unlawfully strikes another.

This inference is strengthened by the fact that the phrase “engages in fighting” is immediately preceded by the phrase, “challenges another to fight”. The act of “challenging” another to fight clearly involves daring or inviting someone else to engage in mutual fighting. And because this first clause of subsection (a)(5) employs the word “fight” in this sense of “mutual fighting”, one can infer that the legislature was referring to the same concept—mutual fighting—when they used the phrase “engages in fighting” in the second clause of the statute.

Under the rule of statutory construction known as noscitur a sociis (literally, “it is known by its associates”), we … conclude that the phrase “fighting other than in self-defense” refers to the same type of mutual fighting as the phrase “challenges another to fight”. That is, both phrases refer to a physical struggle or combat among willing participants.

This conclusion is also bolstered by the disparity in the punishment for assault, and even the punishment for harassment, versus the punishment for disorderly conduct. [Misdemeanor assault is punishable up to one year in jail whereas the maximum punishment for disorderly conduct is 10 days.]

[…]

The fact that a person who is found guilty of disorderly conduct for “engaging in fighting other than in self-defense” faces such a minimal penalty compared to the sentences that can be imposed for assault or even harassment suggests to us that the legislature viewed disorderly conduct as a significantly lesser offense. But this view of disorderly conduct would make little sense if “fighting” included all instances where one person unlawfully strikes or offensively touches another person. The disparity in punishment suggests that the legislature took a narrower view of “fighting”—the view that “fighting” referred to instances of fighting between mutually willing participants.

If the legislature viewed “fighting” in this more limited sense, then it would be reasonable for the legislature to impose greater punishments for assault and for harassment (which includes non-consensual offensive touchings, as well as “insults, taunts, and challenges” that are likely to provoke immediate violence). When an assault leads to combat, it will be a combat where one participant is at fault and the other participant is exercising the right of self-defense. And when harassment leads to combat, it will be a combat where one participant is significantly more at fault than the other. In cases of mutual “fighting”, on the other hand, there is no primary offender or victim; this conduct is punished only because the turmoil of the fight could breach or threaten the public peace.

[…]

For these reasons, we conclude that the phrase “engages in fighting other than in self-defense” (as used in subsection (a)(5) of our disorderly conduct statute) does not include one-sided attacks of one person upon another—i.e., acts punishable as assault, or acts punishable as harassment under AS 11.61.120(a)(5) (subjecting another person to offensive physical contact). Rather, the phrase “engages in fighting other than in self-defense” is limited to altercations where the parties share a mutual intent or willingness to fight.

It is possible that in some cases where a defendant is charged with assault, the evidence may give rise to a reasonable possibility that the defendant is not guilty of assault but rather of the lesser crime of disorderly conduct under the “engages in fighting” clause of AS 11.61.110(a)(5). It is also possible that the evidence may give rise to a reasonable possibility that the defendant is guilty of the lesser crime of harassment under either AS 11.61.120(a)(1) (insulting, taunting, or challenging another person in a manner likely to provoke an immediate violent response) or AS 11.61.120(a)(5) (subjecting another person to offensive physical contact).

If the government has not already charged these lesser crimes as alternative offenses, and if the evidence presented at trial is sufficient to support the conclusion that the defendant is not guilty of assault but is instead guilty of one or (conceivably) both of these lesser offenses, then either party may request a jury verdict on these lesser offenses. In such cases, the jurors should be instructed that they cannot return a verdict on a lesser offense unless they have reached unanimous agreement that the defendant should be acquitted of the charged assault.

[…]

Conclusion

The judgement of the district court is AFFIRMED.

Riot

Riot is violent, dangerous group behavior. Collective, group action can quickly become out-of-control mobs destroying property and injuring scores of innocent victims. When groups begin to engage in dangerous and violent behavior, the individual members are guilty of riot. Before a person can be convicted of the crime of riot, however, they must participate with five or more people in tumultuous and violent conduct in a public place, which creates a substantial risk of causing property damage or personal injury. AS 11.61.100. Riot is a low-level felony.

Riot is a very restrictive statute. The law requires that the rioter’s conduct be both tumultuous and violent. It must be more than just a loud noise or a minor disturbance. It must involve ominous threats of physical injury or property damage. Merely tumultuous conduct is insufficient and likely interferes with a person’s rights of speech and assembly. See e.g., Marks v. Anchorage, 500 P.2d 644, 653-54 (Alaska 1972). The phrase “tumultuous behavior,” standing alone, encompasses “conduct ranging from actual violence to speaking in a loud and excited manner.” Id. Mere tumultuous behavior leaves an officer with unfettered discretion that infringes upon a citizen’s rights of speech and assembly. Before a person is guilty of riot the group must engage in violent or destructive behavior.

As a practical matter, in the event of a riot, rioters are frequently arrested for the crimes that are actually committed, or attempted to be committed, and not riot (assuming that they are even arrested). For example, if a rioter throws a firebomb against a building or assaults an innocent bystander, the rioter is likely to be charged with arson and assault, respectively, and not necessarily riot. Likewise, a mob that overturns a police car in the middle of the street will be prosecuted for criminal mischief, irrespective of whether the mob is also charged with riot. Riot, although an important criminal offense, is difficult to prove and is rarely charged.

Harassment

Harassment criminalizes serious, but still somewhat trivial, conduct that interferes with a person’s personal autonomy. Harassment, like disorderly conduct, is a “catch-all” type of criminal statute. Harassment, unlike disorderly conduct, focuses on conduct that is intentionally harassing or annoying to another person – usually through a series of specific actions like spitting, taunting, prank phone calls, unwanted sexting, cyberbullying, or offensive touching. Accidental annoyance does not qualify. The crime is broken into two degrees, both of which are misdemeanors. Compare AS 11.61.118(a)(b) and 11.61.120(b).

Harassment is a specific intent crime – the defendant must act with the “intent to harass or annoy” another person. First-degree harassment, the most-serious degree of harassment, covers relatively specific conduct. First, it only occurs if a person subjects another person to offensive physical conduct by throwing bodily fluids onto another person. AS 11.61.118(a)(1). Bodily fluids include human and animal blood, mucus, saliva, semen, urine, vomitus, or feces. As you can see, the statute covers both the person who spits on another person at a baseball game and the inmate who throws feces at correctional officers. Both are guilty of first-degree harassment.

The crime is also committed, however, if a person touches another person’s genitals or buttocks, over clothing, without consent. AS 11.61.118(a)(2). This offensive conduct is not “sexual conduct” for purposes of a sex offense. See State v. Mayfield, 442 P.3d 784 (Alaska App. 2019). This would include a nonconsensual pinch of a stranger’s buttocks in a crowded elevator. Recall Townsend, the individual who grabbed Tim’s genitals in the downtown Juneau bar. Townsend was only guilty of first-degree harassment, not sexual assault. State v. Townsend, 2011 WL 4107008 (Alaska App. 2011).

Second-degree harassment covers a much broader range of conduct. The statute prohibits insulting, taunting, or challenging another in a manner likely to provoke an immediate and violent response. This subsection criminalizes fighting words. Fighting words are more than merely challenging another person to fight (such conduct would constitute disorderly conduct). This subsection focuses on whether a reasonable person would be provoked into an immediate breach of peace. AS 11.61.120(a)(1). Recall it is virtually impossible to prosecute someone for taunting a police officer with fighting words. See e.g. Anniskette v. State, 489 P.2d 1012 (Alaska 1971). No reasonable police officer would be provoked by mere words. The average citizen, on the other hand, is not expected to show such restraint.

The communication need not occur face-to-face. The statute includes sending an electronic communication that insults, taunts, challenges, or intimidates a minor and places the minor in reasonable fear of physical injury. AS 11.61.120(a)(7). Cyberbullying would fall within this subsection.

The statute also criminalizes making annoying, threatening, or obscene phone calls or other electronic communications. A person may not call another person with the intent to impair the ability of the person to place or receive telephone calls. AS 11.61.120(a)(2). A person may not make repeated telephone calls at extremely inconvenient hours. AS 11.61.120(a)(3). And, a person may not make a single obscene or threatening telephone call. AS 11.61.120(a)(5). All of this conduct is captured by second-degree harassment. These subsections are intended to stop prank and harassing phone calls. The advent of call-waiting and cellular phones have largely rendered the statute superfluous, but can still be used to deter repeated and extremely inconvenient phone calls.

Sharing or sending sexually explicit photos or videos without the consent of the victim falls with second-degree harassment. Compare AS 11.61.120(a)(6) and (a)(8). Specifically, the statute prohibits sharing images or videos that show “the genitals, anus, or female breast” of another person without the person’s consent. AS 11.61.120(a)(6). Put another way, if a person shares otherwise private sexually explicit images or videos, the person is guilty of second-degree harassment. This conduct is sometimes referred to as revenge porn. The statute also criminalizes the sending of unwanted sexual images or videos. AS 11.61.120(a)(8).

Finally, the statute prohibits subjecting another person to offensive physical contact. AS 11.61.120(a)(5). While this is similar to the prohibition set forth in first-degree harassment, the contact does not involve another person’s genitals, buttocks, or female breast. Instead, the conduct would include minor shoves or slaps that do not qualify as “physical injury” under assault.