Freedom of Speech

The First Amendment states, in relevant part, “Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech.” Although this language specifically targets Congress, the First Amendment has been held applicable to the states by virtue of selective incorporation. See Gitlow v. New York, 268 U.S. 652 (1925). Most states, like Alaska, have a similar constitutional provision protecting freedom of speech. In fact, the Alaska Constitution recognizes that although all citizens have the right to speak freely, they are equally responsible for the consequences of such speech.

“Every person may freely speak, write, and publish on all subjects, being responsible for the abuse of that right.”

Alaska Constitution, Art. 1, §5.

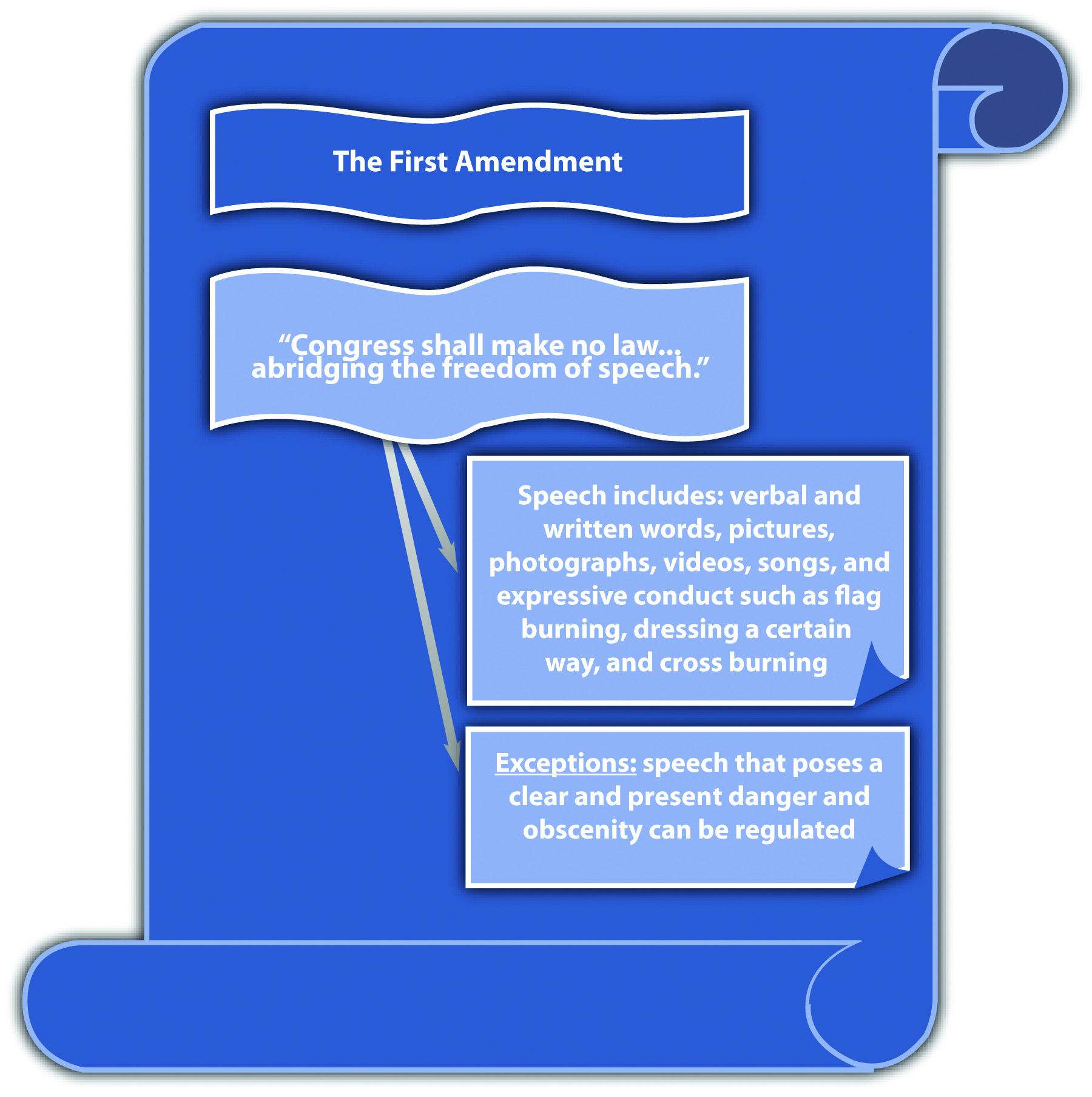

Freedom of speech is frequently referred to as “the bedrock of a democratic society.” Our Founding Fathers believed that a robust, free exchange of ideas was the great shield against tyranny and memorialized this principle in the free speech clause of the First Amendment. The First Amendment prevents the government from restricting (and criminalizing) our expressions, ideas, messages, and content. The word speech has been interpreted to cover virtually any form of expression, including verbal and written words, pictures, photographs, videos, and songs. First Amendment speech not only covers words and ideas, but also symbolic speech, including expressive conduct such as dressing a certain way (Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, 393 U.S. 503 (1969)), flag burning (Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 (1989)), and cross burning (R.A.V. v. St. Paul, 505 U.S. 377 (1992)).

However, even though our free speech is paramount to a well-functioning democracy, it is not limitless. Not all speech is protected. When limiting a person’s speech, the court conducts a balancing test – the court must weigh an individual’s right to free expression against society’s interest in a safe, secure, and peaceful community.

Exceptions to the First Amendment’s Protection of Free Speech

In general, courts have examined the history of the Constitution and the policy supporting freedom of speech when creating exceptions to its coverage. Modern decisions afford freedom of speech the strictest level of scrutiny; only a compelling government interest can justify an exception, which must use the least restrictive means possible. See Sable Communis. of California, Inc. v. FCC, 492 U.S. 115 (1989). For brevity, this book reviews the constitutional exceptions to free speech in statutes criminalizing fighting words, incitement to riot, true threats, hate crimes, and obscenity.

Figure 3.5 The First Amendment

Fighting Words

Although the First Amendment protects peaceful speech and assembly, if speech creates a clear and present danger to the public, it can be regulated. Schenck v. U.S., 249 U.S. 47 (1919). This includes fighting words, or “those [words] which by their very utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace.” See Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U.S 568, 572 (1942).

Any criminal statute prohibiting fighting words must be narrowly tailored and focus on imminent rather than future harm. Modern US Supreme Court decisions indicate a tendency to favor freedom of speech over the government’s interest in regulating fighting words, and many fighting words statutes have been deemed unconstitutional under the First Amendment or void for vagueness and overbreadth under the Fifth Amendment and Fourteenth Amendment due process clause. The Alaska case, Anniskette v. State, 489 P.2d 1012 (Alaska 1971), included below demonstrates the judiciary’s concern of governmental overreach when criminalizing “mean” words.

Example of an Unconstitutional Fighting Words Statute

Georgia enacted the following criminal statute: “Any person who shall, without provocation, use to or of another, and in his presence…opprobrious words or abusive language, tending to cause a breach of the peace…shall be guilty of a misdemeanor.” See former Ga. Code § 26-6303. The US Supreme Court determined that this statute was vague and overbroad, and unconstitutional under the First Amendment. See Gooding v. Wilson, 405 U.S. 518 (1972).

The Court noted that “[b]ecause First Amendment freedoms need breathing space to survive, government may regulate in the area only within narrow specificity.” See id. at 522. The Court held that the dictionary definitions of “opprobrious” and “abusive” gave government greater reach than fighting words. Thus the statute was overbroad since it did not restrict its prohibition to imminent harm. The terms opprobrious and abusive have various meanings, so the statute is subject to uneven enforcement and is void for vagueness. As the Court stated, this statute “licenses the jury to create its own standard in each case.” See id. at 528 (citing Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U.S. 242, 263 (1937)).

Incitement to Riot

Inciting a riot is not protected speech. Incitement to riot is regulated under the clear and present danger exception. Similar to fighting words, an incitement to riot statute must prohibit imminent lawless action. See Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969). Statutes that prohibit simple advocacy with no imminent threat or harm cannot withstand the First Amendment’s heightened scrutiny.

Brandenburg .v Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969)

In Brandenburg v. Ohio, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down a statute that criminalized “advocat[ing]…the duty, necessity, or propriety of crime, sabotage, violence, or unlawful methods of terrorism as a means of accomplishing industrial or political reform” and “voluntarily assembl[ing] with any society, group or assemblage of persons formed to teach or advocate the doctrines of criminal syndicalism”. See former Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2923.13. An excerpt of the case is included below. Notice how the Court focused on the difference between simple advocacy and incitement to violence.

89 S.Ct. 1827

Supreme Court of the United States

Clarence BRANDENBURG, Appellant,

v.

State of OHIO.

No. 492.

Argued Feb. 27, 1969.

Decided June 9, 1969.

Opinion

PER CURIAM.

The appellant, a leader of a Ku Klux Klan group, was convicted under the Ohio Criminal Syndicalism statute for[:]

‘advocat(ing) * * * the duty, necessity, or propriety of crime, sabotage, violence, or unlawful methods of terrorism as a means of accomplishing industrial or political reform’ and for ‘voluntarily assembl(ing) with any society, group, or assemblage of persons formed to teach or advocate the doctrines of criminal syndicalism.’ […]

[See former Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2923.13.]

He was fined $1,000 and sentenced to one to 10 years’ imprisonment. The appellant [Brandenburg] challenged the constitutionality of the criminal syndicalism statute under the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution, but the intermediate appellate court of Ohio affirmed his conviction without opinion. The Supreme Court of Ohio dismissed his appeal … Appeal was taken to this Court, and we noted probable jurisdiction. We reverse.

The record shows that a man, identified at trial as the appellant, telephoned an announcer-reporter on the staff of a Cincinnati television station and invited him to come to a Ku Klux Klan ‘rally’ to be held at a farm in Hamilton County. With the cooperation of the organizers, the reporter and a cameraman attended the meeting and filmed the events. Portions of the films were later broadcast on the local station and on a national network.

The prosecution’s case rested on the films and on testimony identifying the appellant as the person who communicated with the reporter and who spoke at the rally. The State also introduced into evidence several articles appearing in the film, including a pistol, a rifle, a shotgun, ammunition, a Bible, and a red hood worn by the speaker in the films.

One film showed 12 hooded figures, some of whom carried firearms. They were gathered around a large wooden cross, which they burned. No one was present other than the participants and the newsmen who made the film. Most of the words uttered during the scene were incomprehensible when the film was projected, but scattered phrases could be understood that were derogatory of Negroes and, in one instance, of Jews. Another scene on the same film showed the appellant, in Klan regalia, making a speech. The speech, in full, was as follows:

‘This is an organizers’ meeting. We have had quite a few members here today which are—we have hundreds, hundreds of members throughout the State of Ohio. I can quote from a newspaper clipping from the Columbus, Ohio Dispatch, five weeks ago Sunday morning. The Klan has more members in the State of Ohio than does any other organization. We’re not a revengent organization, but if our President, our Congress, our Supreme Court, continues to suppress the white, Caucasian race, it’s possible that there might have to be some revengeance taken.

‘We are marching on Congress July the Fourth, four hundred thousand strong. From there we are dividing into two groups, one group to march on St. Augustine, Florida, the other group to march into Mississippi. Thank you.’

The second film showed six hooded figures one of whom, later identified as the appellant, repeated a speech very similar to that recorded on the first film. The reference to the possibility of ‘revengeance’ was omitted, and one sentence was added: ‘Personally, I believe the nigger should be returned to Africa, the Jew returned to Israel.’ Though some of the figures in the films carried weapons, the speaker did not.[…]

1927, this Court sustained the constitutionality of [a substantially similar law, the] California’s Criminal Syndicalism Act. …[U.S. Supreme Court precedent has] fashioned the principle that the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not permit a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or of law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action. As we said in Noto v. United States, 367 U.S. 290 (1961),

‘the mere abstract teaching … of the moral propriety or even moral necessity for a resort to force and violence, is not the same as preparing a group for violent action and steeling it to such action.’ A statute which fails to draw this distinction impermissibly intrudes upon the freedoms guaranteed by the First and Fourteenth Amendments. It sweeps within its condemnation speech which our Constitution has immunized from governmental control.

Measured by this test, Ohio’s Criminal Syndicalism Act cannot be sustained. The Act punishes persons who ‘advocate or teach the duty, necessity, or propriety’ of violence ‘as a means of accomplishing industrial or political reform’; or who publish or circulate or display any book or paper containing such advocacy; or who ‘justify’ the commission of violent acts ‘with intent to exemplify, spread or advocate the propriety of the doctrines of criminal syndicalism’; or who ‘voluntarily assemble’ with a group formed ‘to teach or advocate the doctrines of criminal syndicalism.’ Neither the indictment nor the trial judge’s instructions to the jury in any way refined the statute’s bald definition of the crime in terms of mere advocacy not distinguished from incitement to imminent lawless action.

Accordingly, we are here confronted with a statute which, by its own words and as applied, purports to punish mere advocacy and to forbid, on pain of criminal punishment, assembly with others merely to advocate the described type of action. Such a statute falls within the condemnation of the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

[…]

Reversed.

True Threats

Courts have long recognized that the First Amendment does not prohibit a state from criminalizing “true threats”- that is, threats to cause harm to another person. States have a legitimate interest in preventing persons from engaging in speech that unjustifiably creates an objective, reasonable fear. Although a person may have a fundamental right to express abusive, caustic, or offensive views, no one has the right to threaten physical violence. States can, and frequently do, criminalize such conduct. What constitutes a threat, however, must be distinguished from what constitutes constitutionally protected speech.

“True threats” encompass those statements where the speaker means to communicate a serious expression of an intent to commit an act of unlawful violence to a particular individual or group of individuals. The speaker need not actually intend to carry out the threat. Rather, a prohibition on true threats “protect[s] individuals from the fear of violence[.]”

See Virginia v. Black, 538 U.S. 434, 359-60 (internal citations omitted).

Although the government need not prove the defendant intended to carry through with the threat, the government bears the burden of proving that the utterance was more than simple hyperbole. This determination requires the court to view the defendant’s speech in context, weighing the reaction of the listeners and its conditional nature (if any). See e.g., Watts v. United States, 394 U.S. 705, 708 (1969). This is not always an easy task.

Nonetheless, Alaska has enacted several criminal statutes that proscribe threats of physical violence or criminalize conduct that may cause a reasonable person to be afraid. For example, second-degree terroristic threatening criminalizes making a threat that causes an evacuation of a public building (e.g., a bomb threat). AS 11.56.810(a)(1)(b). Stalking, on the other hand, criminalizes a pattern of nonconsensual contact that causes a reasonable person to be placed in fear. AS 11.41.270. We will explore these crimes, and others, in subsequent chapters, but for now recognize that whenever the government seeks to proscribe threatening conduct, the First Amendment may limit the reach of the proposed crime.

Hate Crimes

Many states and the federal government have enacted hate crimes statutes. When hate crime statutes criminalize speech, including expressive conduct, a First Amendment analysis is appropriate. When hate crimes statutes enhance a penalty for criminal conduct that is not expressive, the First Amendment is not applicable. See Wisconsin v. Mitchell, 508 U.S. 476 (1993). In Alaska, hate crimes are subject to enhanced punishment. AS 12.55.155(c)(22).

Hate crimes statutes punish conduct that targets a specific classifications of people. These classifications are listed in the statute and can include race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, or religion. Hate crimes statutes that criminalize speech may be constitutional under the clear and present danger exception if they are tailored to apply only to speech or expressive conduct that is supported by an intent to intimidate. See Virginia v. Black, 538 U.S. 343 (2003). This can include speech or expressive conduct such as threats of imminent bodily injury, death, or cross burning. As with all criminal statutes that implicate the First Amendment, hate crimes statutes must be narrowly drafted, and will be struck down if vague or overbroad.

Hate crimes statutes that criminalize the content of speech, like a prejudicial opinion about a certain race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, or religion, are unconstitutional under the First Amendment. See R.A.V. v. St. Paul, 505 U.S. 377 (1992). Statutes that criminalize content-based speech have a “chilling effect” on free expression by deterring individuals from expressing unpopular views, which is the essence of free speech protection. Although this type of speech can stir up anger, resentment, and possibly trigger a violent situation, the First Amendment protects content-based speech from governmental regulation unless the government can demonstrate a compelling state interest.

Is Cross Burning Constitutional?

Cross burning has a long and violent history in America, one that is intertwined with the rise of the Ku Klux Klan. Several jurisdictions have sought to criminalize such conduct due to its violent and intimidating nature. Whether such laws withstand First Amendment scrutiny, however, largely depends on whether the law targets the content of speech or the conduct at issue (regardless of the speech’s content).

An Unconstitutional Statute Prohibiting Cross Burning

St. Paul, Minnesota, enacted the Bias-Motivated Crime Ordinance, which prohibited the display of a symbol that a person knows or has reason to know “arouses anger, alarm or resentment in others on the basis of race, color, creed, religion or gender” See former Ordinance, St. Paul, Minn., Legis. Code § 292.02 (1990). In R.A.V. v. St. Paul, the US Supreme Court held that this ordinance was unconstitutional on its face because the regulation was based on the content of speech, with no additional requirement for imminent lawless action. The Court held that the ordinance did not proscribe the use of fighting words (the display of a symbol) toward specific groups of individuals, which would be an equal protection clause challenge. Instead, the Court determined that the statute prohibited the use of specific types of fighting words – that is, words that promote racial hatred. This was impermissible viewpoint-based censorship. As the Court stated, content-based regulations “are presumptively invalid.” See id. at 382 (citations omitted).

Compare the St. Paul ordinance discussed above with the Virginia statute below.

A Constitutional Statute Prohibiting Cross Burning

Virginia enacted a statute that made it criminal “for any person…, with the intent of intimidating any person or group…, to burn…a cross on the property of another, a highway or other public place.” See Va. Code Ann. § 18.2-423. The US Supreme Court held this statute constitutional under the First Amendment because it did not single out cross-burning indicating racial hatred, unlike the Minnesota cross-burning ordinance, but instead required the government to prove that the accused acted with the intent to intimidate. The Court stated, “[u]nlike the statute at issue in R. A. V., the Virginia statute does not single out for opprobrium only that speech directed toward ‘one of the specified disfavored topics.'” See Virginia v. Black, 538 U.S. 343, 362 (2003) (citations omitted). [Under the Virginia statute] it does not matter whether an individual burns a cross with intent to intimidate because of the victim’s race, gender, or religion, or because of the victim’s “political affiliation, union membership, or homosexuality.” See id. According to the Court, this was constitutional since the ordinance was content-neutral.

Anniskette v. State, 489 P.2d 1012 (Alaska 1971)

The following Alaska case, Anniskette v. State, 489 P.2d 1012 (Alaska 1971), demonstrates how the court analyzes a potential challenge to a criminal statute under the First Amendment. As you read the case, ask yourself whether you believe the court is treating the victim differently than other citizens given his profession.

489 P.2d 1012

Supreme Court of Alaska.

Ralph ANNISKETTE, Appellant,

v.

STATE of Alaska, Appellee.

No. 1231.

Oct. 15, 1971.

Before BONEY, C. J., and DIMOND, RABINOWITZ, CONNOR and ERWIN, JJ.

OPINION

CONNOR, Justice.

Appellant was convicted by a district court jury of disorderly conduct and disturbance of the peace under AS 11.45.030. The complaint stated that on or about August 22, 1969, Ralph Anniskette ‘did unlawfully conduct himself in a disorderly manner in his home to the disturbance of an Alaska State Trooper, Lorn Campbell, by telephoning Trooper Campbell and berating him with loud and abusive language.’

It seems that appellant regularly telephoned the local resident trooper and complained at length regarding the trooper’s qualifications and performance. Repeated calls were often made late at night while appellant was apparently intoxicated. The trooper and his family became increasingly upset with such recurrent harassment, which occurred even while the trooper was out of town.

However, appellant was charged with making but a single telephone call on August 22, 1969. The call was from appellant’s home to Trooper Campbell’s home. During the course of that conversation, he complained at length regarding the trooper’s effectiveness, and even questioned whether the trooper was properly qualified to be a law-enforcement official.[1]

At his trial, appellant moved to dismiss the charge for failure to state an offense under AS 11.45.030. If an offense was stated, it was, he argued, an unconstitutional application of the statute. Alternatively, he asserted that the statute was unconstitutionally vague on its face, and that it constituted an invalid prior restraint on his freedom of speech. His motion was denied. He was convicted in the district court and appealed to the superior court. Upon affirmance of his conviction by that court, this appeal followed.

…

This is not a case in which a comprehensive interpretation of the disorderly conduct statute is required. Whatever the statute means, it cannot be applied to behavior which is constitutionally exempt from criminal prohibition. It must be recognized at the outset that it is communicative utterances which are the subject of prosecution. They constitute the sole form of behavior for which the defendant was prosecuted.

Under the First Amendment to the Constitution, it is only in the most limited circumstances that speech may be punished. Certainly the defendant’s conduct does not fall within the unprotected area of ‘obscenity’. No claim is made that Anniskette’s message was erotically arousing. See Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15 (1971). The defendant did not use ‘profanity’ of the type which creates in and of itself a public nuisance. At least no such ‘profanity’ is charged here.[2] Writing for the court in Cohen, Mr. Justice Harlan pointed out that coarse words must often be a necessary concomitant to achieving those values which open debate and free speech are designed to serve:

‘Against this perception of the constitutional policies involved, we discern certain more particularized considerations that peculiarly call for reversal of this conviction. First, the principle contended for by the State seems inherently boundless. How is one to distinguish this from any other offensive word? Surely the State has no right to cleanse public debate to the point where it is grammatically palatable to the most squeamish among us. Yet no readily ascertainable general principle exists for stopping short of that result were we to affirm the judgment below. For, while the particular four-letter word being litigated here is perhaps more distasteful than most others of its genre, it is nevertheless often true that one man’s vulgarity is another’s lyric. Indeed, we think it is largely because governmental officials cannot make principled distinctions in this area that the Constitution leaves matters of taste and style so largely to the individual.’ [citations omitted]

Nor can we find in defendant’s telephone call an exhortation to violence by others which creates a clear and present danger that such violence will occur.

We cannot classify the defendant’s telephonic communication as falling within the category of ‘fighting words’, which is recognized as another exception to the freedom of speech guaranteed by the Constitution. The ‘fighting words’ doctrine covers those face-to-face utterances which ordinarily provoke, in the average, reasonable listener, an immediate violent response. The defendant’s conduct in this case did not reach that degree of provocation.

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568 (1942), is not apposite. It concerns a narrowly construed statute prohibiting ‘face-to-face words plainly likely to cause a breach of the peace by the addressee’. An important distinguishing feature of Chaplinsky is that the words, ‘You are a God damned racketeer’ and ‘a damned Fascist and the whole government of Rochester are Fascists or agents of Fascists’, were uttered at a street intersection where the listening crowd had become unruly, and after a disturbance in the crowd had actually occurred. Because these words, in context, tended to incite an immediate breach of the peace, they were held not to be protected as free speech

But here the situation is quite different. For even if it were assumed for purposes of argument that Anniskette’s message contained ‘fighting words’, constitutional protection would still extend to the particular factual setting presented here. The time necessary for the officer to travel from his residence to that of the defendant should have allowed enough cooling off so that any desire on the part of the officer to inflict violence on the defendant should have been dissipated. We assume that the officer had sufficient self-control that, after such a period of time, he would not have assaulted the defendant for what had been said earlier. As another court has observed,

‘A policeman’s special powers and training, and his constant exposure to situations where the norms of common speech are not distinguished by unvarying delicacy of expression, leave him less free to react as quickly as the private citizen to a purely verbal assault. In a situation where he is both the victim of the provocative words of abuse and the public official entrusted with a discretion to initiate through arrest the criminal process, the policemen may, ordinarily at least, be under a necessity to preface arrest by a warning. It would appear that there is no First Amendment right to engage in deliberate and continued baiting of policemen by verbal excesses which have no apparent purpose other than to provoke a violent reaction.’

Williams v. District of Columbia, 419 F.2d 638, 646, n. 23 (1969).

That the officer was personally offended by the telephone call does not render the defendant’s conduct a crime. That would be to make the terms of the statute and the content of the First Amendment shift with the mentation and emotional status of the recipient of the verbal communication. Under an objective standard it is not permissible to make criminality hinge upon the ideological vicissitudes of the listener. A great deal more is required to place speech outside the pale of First Amendment protection. The point was made forcefully [by the United States Supreme Court] in Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1, 4 (1949):

‘Speech is often provocative and challenging. It may strike at prejudices and preconceptions and have profound unsettling effects as it presses for acceptance of an idea. That is why freedom of speech, though not absolute, (citing Chaplinsky) is nevertheless protected against censorship or punishment, unless shown likely to produce a clear and present danger of a serious substantive evil that rises far above public inconvenience, annoyance, or unrest.’

…

We understand the difficulties encountered by a state trooper in a small community, where village vexations at times can reach a fever pitch. We may even view appellant’s conduct with personal disapproval. But we find neither legislative language nor constitutional power to read the statute as including within its ambit a single telephone call criticizing a public officer for the performance of his official duties. [citations omitted]

In the light of these constitutional mandates … [w]e hold that defendant’s conduct did not constitute a crime.

We reverse and remand with direction that the complaint be dismissed.

Reversed.

[1] The trooper testified that:

‘Mr. Anniskette-he told me I was a no good goddam cop and that he had a call into Juneau right now to find out if I was a State trooper and that when they had their own policeman that they never had the problems that since I’d been over there that they have with their kids drinking, that what was I gonna’ do about a subject named Ernie Fawcett (phonetic) who had stabbed a Marvin Milton (phonetic), that the was still running on the street and that if he got to checking that he’ll bet that I didn’t even report this and make a report concerning this, and he went on and on over the same type of things.’

[2] The expletive, ‘no good goddamn cop’, merely as a part of a more generalized conversation, would hardly rise to the level of profanity which can constitutionally be reached by the criminal law. […]

Obscenity

Another exception to free speech is obscenity; obscene speech is not protected speech. Obscenity is usually conveyed by speech, such as words, pictures, photographs, songs, videos, and live performances. See generally Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476, 484-86 (1957). “Obscene”, however, is not easily defined. As Justice Stewart famously explained, in his view, obscenity may be “indefinable … [b]ut I know it when I see it.” See Jacobellis v. Ohio, 378 U.S. 184, 197 (1964) (Stewart, J., concurring).

In Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15 (1973), the US Supreme Court devised a three-part test to ascertain if speech is obscene and subject to government regulation. Generally, speech is obscene if (1) the average person, applying contemporary community standards would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest in sex; (2) it depicts sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law in a patently offensive way; and (3) it lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value. See id.

Example of Speech That Is Not Obscene

In Jenkins v. Georgia, 418 U.S. 153 (1974), the US Supreme Court viewed the film Carnal Knowledge to determine whether the defendant could be constitutionally convicted under an obscenity statute for showing it at a local theater. The Court concluded that most of the film’s sexual content was suggestive rather than explicit, and the only direct portrayal of nudity was a woman’s bare midriff. Thus although a jury convicted the defendant after viewing the film, the Court reversed the conviction, stating that the film does not constitute the hard-core pornography that the three-part test for obscenity isolates from the First Amendment’s protection. The Court stated, “Appellant’s showing of the film ‘Carnal Knowledge’ is simply not the ‘public portrayal of hard core sexual conduct for its own sake, and for the ensuing commercial gain’ which we said was punishable in Miller.” See Jenkins, at 161 (internal citations omitted).

Nude Dancing

Statutes that regulate nude dancing have also been challenged under the First Amendment. While the US Supreme Court has found that nude dancing falls within a constitutionally protected expression, it has noted that nude dancing falls only “within the outer ambit of First Amendment protection.” See City of Erie et al v. Pap’s A.M., 529 U.S. 277, 289 (2000). The US Supreme Court has generally upheld government reasonable regulation of erotic dancing, such as requirements that nude dancers wear pasties and a g-string. See id. The Court has noted that the government has a legitimate interest in preventing negative secondary effects (i.e., prostitution, excessive noise, traffic congestion, etc.).

The Alaska Supreme Court, interpreting the Alaska Constitution, has noted that sexually-oriented speech is not less worthy of protection than other types of speech. In the eyes of the Alaska Supreme Court, nude dancing is a form of free expression and any government regulation must be narrowly tailored to achieve its result (strict scrutiny). See Club SinRock LLC v. Anchorage, 445 P.3d 1031, 1037-38 (Alaska 2019).