Infancy, Intoxication, Ignorance, and Mistake

Infancy

At common law, infancy was a defense to crime. Infancy asserts that the defendant should not be subject to criminal prosecution because he or she is too young to appreciate the nature of “crime.” Legally, the infancy defense recognizes that certain juveniles are simply too immature to form the culpable mental state necessary to commit a crime. Morally, the infancy defense recognizes that juveniles are simply too immature to be punished for a crime.

The common law recognized three age-based categories of increasing criminal responsibility. If an offender was under the age of seven years old, the offender lacked the capacity to form the requisite culpable mental state. The minor could not be criminally prosecuted. If a minor was between seven and fourteen years old, there was a rebuttable presumption that the offender lacked the necessary capacity. The court presumed that the offender lacked capacity, but the government could rebut the presumption with sufficient evidence. Finally, common law held that all offenders over fourteen years old could form the necessary mental state.

All modern American jurisdictions have moved away from the graded presumptions surrounding infancy and instead created juvenile justice systems. All juvenile justice systems include a mechanism to allow the most serious juvenile offenders to be prosecuted in adult court. Alaska is no different.

Juvenile Justice System

In 1899, the Illinois Juvenile Court Act created the first juvenile court. The new juvenile court introduced a special adjudicatory proceeding for delinquent youths, separate from adult court. Several states soon followed suit. The idea behind juvenile courts was to concentrate on the rehabilitative potential of minors, emphasizing an informal court structure. Under this model, juveniles were not viewed as criminals, but as troubled youths in need of supervision. A juvenile offender was never convicted of a crime; instead, the youth was adjudicated a delinquent in need of rehabilitation.

During the 1950s and 1960s, scholars began to question how juveniles were being treated in juvenile justice systems across the county. Although the philosophy of juvenile courts was still seen as benevolent, the scholars believed that significant arbitrariness existed within the various systems, raising constitutional concerns. Beginning in 1967, the US Supreme Court began providing juveniles with constitutional due process protections.

The seminal juvenile law case, In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1987), involved a young boy who was arrested for making crank phone calls to his neighbor. Neither the boy, nor his parents, received notice of the charges, assistance of counsel, or an opportunity to cross-examine witnesses. After being adjudicated a delinquent youth, the trial judge ordered the young boy to Arizona Industrial School for an indeterminate period not to exceed six years. The maximum penalty for an adult convicted of the same offense was two months in jail or a fifty-dollar fine. Because of the inequality between youths and adults, the Court held that juveniles were entitled to adequate notice of charges, the assistance of counsel, the privilege from self-incrimination, and the right to confront witnesses during delinquency proceedings.

Since Gault, the US Supreme Court has repeatedly affirmed that juveniles have the right to avail themselves of basic constitutional protections. Today, juveniles are afforded nearly all of the same adult constitutional protections when facing delinquency charges.

Like all states, Alaska’s juvenile justice system is a creature of statute. See AS 47.12. et. seq. With various exceptions, all “minor[s] under 18 years of age” at the time of a criminal offense are handled within the juvenile justice system. AS 47.12.020. The primary purpose of the juvenile system is rehabilitation, not punishment. Juveniles are not “convicted” of crime, but instead are determined to be “delinquent.” Delinquent minors are committed to the care of the Department of Health and Social Services, not the Department of Corrections. The Alaska Criminal Rules do not apply to juvenile proceedings. Juvenile matters are governed by the delinquency rules. See Alaska Delinquency Rules 1(b).

Yet, Alaska’s juvenile justice system, like most states, has significant exclusions. Certain minors, who commit certain offenses, are excluded from the juvenile system as a matter of law. In Alaska, this includes most serious felony crimes if the juvenile was 16 or 17 at the time of the offense. Thus, a 16-year-old accused of murder must be prosecuted in adult court, not juvenile court. This is commonly referred to as automatic waiver. The term is largely a misnomer in Alaska. The juvenile is never “waived” to adult court; instead, the juvenile justice system never had jurisdiction. Older juveniles (16- or 17-year-olds) who commit serious offenses are excluded from the juvenile system’s jurisdiction. Likewise, most misdemeanor traffic, wildlife, and tobacco criminal violations are handled in adult court. Although juveniles have significant constitutional protections within the juvenile system, juveniles have no constitutional right to a juvenile justice system. The Alaska legislature is free to determine which minors are prosecuted in adult court, and which minors are adjudicated in juvenile court. See e.g., Watson v. State, 487 P.3d 568 (Alaska 2021).

A small class of minors are subject to discretionary waiver – that is, minors who commit serious offenses and are “not amenable to treatment” in the juvenile system. These minors may be waived (e.g., transferred) to the adult court system at the discretion of the court. AS 47.12.100. Generally, the burden is on the government to demonstrate that the minor is not amenable to treatment within the juvenile system. However, if the minor is accused of a serious felony offense, the minor must demonstrate that he or she should not be waived. Several factors inform the court’s decision, including the nature of the offense, the sophistication it requires, the minor’s criminal history, and the threat the minor poses to public safety.

Example of the Juvenile Justice System

Robbie is fourteen years old. Robbie shoplifts a “hacky sack” to impress his friends. An off-duty police officer sees Robbie steal the Hacky Sack and arrests him when he walks out of the store. Robbie committed the crime of fourth-degree theft. Although the Anchorage District Attorney wants to make an example of Robbie, Alaska statute specifies that the juvenile justice system has jurisdiction over Robbie’s delinquent conduct. The Anchorage District Attorney would need to persuade the trial court that Robbie was not amenable to treatment within the juvenile system before Robbie could be prosecuted in adult court.

Intoxication

Intoxication is a defense that focuses on a defendant’s inability to form the requisite culpable mental state. Intoxication can be based on the defendant’s ingestion of alcohol or drugs, and it can be voluntary or involuntary.

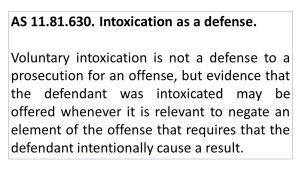

Voluntary intoxication is generally not a defense. Conduct that occurs after the voluntary intoxication is not excused unless the intoxication prevented the defendant from forming the culpable mental state intentionally. When evaluating the culpable mental states of “knowingly,” “recklessly,” and “criminal negligence,” the jury is instructed to assume the defendant was sober. AS 11.81.900(a).

Figure 15.6 – Alaska Statute 11.81.630

Involuntary Intoxication, on the other hand, may be treated as a defense, but recall, it may be analyzed under the voluntary act element requirement of crime. See Wagner v. State, 390 P.3d 1179 (Alaska App. 2012). Involuntary intoxication can occur if the defendant injected a drug or alcohol unknowingly or under force, duress, or fraud.

Ignorance and Mistake

Occasionally, a defendant asserts that he did not know his conduct was criminal. Ignorance of the law is not a defense. AS 11.81.620.

Mistake of law is slightly different. While ignorance is no defense, under a mistake of law defense, the defendant affirmatively asserts that they reasonably believed their criminal conduct was legal. A mistake of law is normally not a defense except in the limited situation where a person acts in reasonable reliance on an official pronouncement (or interpretation) of the law issued by the chief enforcement officer entrusted with the law’s enforcement. See Stoner v. State, 421 P.3d 108 (Alaska App. 2018). Under the mistake of law defense, a defendant is entitled to rely on a judicial officer’s interpretation of a law, but not a police officer’s interpretation. “The policy behind this rule is to encourage people to learn and know the law; a contrary rule would reward intentional ignorance of the law.” See Ostrosky v. State, 704 P.2d 786, 791 (Alaska App. 1985). Mistake of law is an affirmative defense that must be proven by a preponderance of the evidence.

Valid Example of Mistake of Law Defense

Jim is a commercial fisherman working out of Bristol Bay. The Board of Fisheries sets the Bristol Bay sockeye salmon run to be open from June 1 until June 15. On the day of the sockeye salmon opener, the Department of Fish and Game (DFG) issues a proclamation extending the fishery by 48 hours; the fishery will close on June 17, not June 15. Jim works the entire fishery, including the extra two days. Shortly after the fishery closes, the Dillingham Superior Court Judge issues an order finding that DFG usurped the authority of the Board of Fisheries to extend the fishery. An Alaska Wildlife Trooper cites Jim for fishing in closed waters. Under this scenario, Jim would be entitled to rely on a mistake of law defense against the prosecution. Jim could reasonably rely on DFG’s announcement as they are an entity that is entrusted with the enforcement of fish and game rules and regulations.

Invalid Example of Mistake of Law Defense

Susan is on felony probation for check forgery. Susan lives alone and fears for her safety. Susan asks her felony probation officer if she can get a shotgun for home protection. Her probation officer tells her that the restriction on felons owning firearms does not apply to possession of guns in one’s own home if necessary for self-defense. (As you know, this was a legally incorrect statement.) Susan, relying on her probation officer’s advice, buys a shotgun for her home. Police execute a search warrant on Susan’s house (directed at her roommate), and during the subsequent search, police find the shotgun. Susan admits to owning the gun, but claims her probation officer told her it was okay. As harsh as it may seem, Susan does not have a valid mistake of law defense to a felon-in-possession charge. Susan is not entitled to rely on her probation officer’s advice. The probation officer’s opinion as to what the law is does not excuse Susan’s criminal conduct.

Mistake of fact may also be a defense. If a reasonable factual mistake negates the culpable mental state required for the commission of the offense, then the defendant is not criminally responsible. Thus, a person who accidentally picks up another person’s jacket, mistakenly believing it is his own, has not acted with the specific intent to steal – that is, the person has not acted with the requisite culpable mental state. Importantly, a mistake of fact may only operate as a defense when it is a reasonable mistake. An honest, but unreasonable mistake will not absolve a defendant of criminal responsibility. AS 11.81.620(b). A mistake of fact is generally not a defense to strict liability crimes since strict liability crimes have no requisite culpable mental state (mental state is not an essential element of strict liability crimes). See Clucas v. State, 815 P.2d 384, 388 (Alaska App. 1991).

Example of Invalid Mistake of Fact Defense

Tina is pulled over for speeding. Tina claims her speedometer is broken, so she was mistaken as to her speed. Tina probably cannot assert the mistake of fact as a defense in this case. Speeding is generally a strict liability offense; it has no culpable mental state. Tina’s mistaken belief as to the facts of her speed is not relevant because there is no intent required for this offense.