Murder

Murder is the most serious classification of criminal homicide. At common law, murder was defined as the unlawful killing of a human being with “malice aforethought,” either expressed or implied. See Black’s Law Dictionary (6th ed. 2009). Although the term ‘malice aforethought’ has a long, and somewhat confused, history, it generally refers to an evil intent or depraved heart. Express malice existed when the defendant had a deliberate intention to take the victim’s life; implied malice was found when the defendant had a depraved heart or was indifferent to whether the victim lived or died. See e.g., Gray v. State, 463 P.2d 897 (Alaska 1970). Manslaughter, on the other hand, was defined as the unlawful killing without malice aforethought.

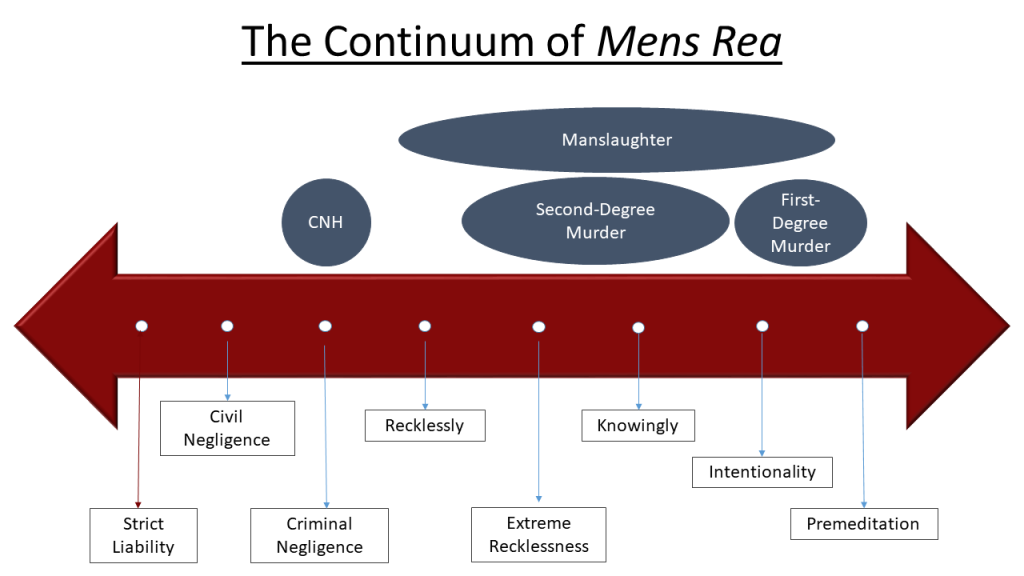

The Alaska criminal code classifies murder based on varying degrees, largely based on the defendant’s culpable mental state at the time of the killing. Generally, it is the mens rea that separates first-degree murder, second-degree murder, manslaughter, and criminally negligent homicide. One important exception is felony-murder, which will be discussed in the next chapter.

Figure 5.1 The Continuum of Homicide Mens Rea

First-Degree Murder

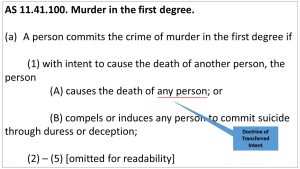

Murder in the first degree is the most serious criminal offense in Alaska. First-degree murder is an unclassified felony with a sentencing range of 30-99 years. AS 12.55.155. While there are multiple different ways to commit first-degree murder, the most frequent is intentional murder. The culpable mental state is intentionally, meaning the defendant must have a conscious objective to cause the victim’s death. AS 11.41.100(a)(1)(A). The statute lists five additional less common ways to commit first-degree murder, including forced suicide, or deaths resulting from repeated child abuse, child kidnapping, or domestic terrorism. See e.g., AS 11.41.100(a)(2)-(5).

Figure 5.2 Alaska Criminal Code – Murder in the First Degree

![AS 11.41.100. Murder in the first degree. A person commits the crime of murder in the first degree if (1) with intent to cause the death of another person, the person (A) causes the death of any person; or (B) compels or induces any person to commit suicide through duress or deception; (2) – (5) [omitted for readability]](https://pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/2614/2022/09/11.41.100-Diagram-300x169.png)

As noted, the most common theory of first-degree murder is intentional murder. Although the defendant must act with a specific intent to kill, the defendant’s intent to kill need not be deliberate or premeditated. Deliberate is normally defined as calm and methodical, without passion or anger. Premediation generally means reflection and planning. Neither is required under Alaska law. A defendant can form the intent to kill in an instant, without reflection, and with intense anger. If the defendant has a conscious objective to cause the victim’s death at the moment he committed the homicidal act, the defendant is guilty of first-degree murder. Although most criminal defendants do not announce their intention before committing a crime, a jury is entitled to presume that a defendant intends the natural and probable consequences of a criminal act he knowingly commits. See Kangas v. State, 463 P.3d 189 (Alaska App. 2020). Thus, a defendant who shoots a person in the chest at near point-blank range is likely to be found to have acted with an intent to cause death because a natural and probable consequence of shooting a person in the chest at point-blank range is death.

Example of Intentional Murder

Frank, Dillon’s supervisor, calls Dillon into his office and unexpectedly fires him. Enraged, Dillon stands up, grabs a heavy brass letter opener from the top of Frank’s desk, yells, “I hope you die!”, and plunges the letter opener into Frank’s chest. Frank stumbles and dies from a severed aorta. Dillon is likely guilty of first-degree murder. Dillon consciously picked up the letter opener and intentionally stabbed Frank in the chest. A severed artery is a natural and probable consequence of stabbing a person in the chest. In fact, Dillon verbalized his intent when he yelled, “I hope you die!” Note that Dillon acted in anger, not with calm, cool reflection. Further, the act of grabbing the letter opener appears impulsive, not planned. There is little evidence that indicates that Dillon has a strong or calculated desire to kill Frank before going into his office. Nonetheless, a jury could find that Dillion intentionally caused the death of Frank.

Transferred Intent

Occasionally, a defendant misses his intended target. Assume A deliberately shoots at B with the intent to kill B, but is a terrible shot, and hits C, killing her instantly. A had the specific intent to kill B, but accidentally killed C. Should A be guilty of first-degree murder (intentional murder), when A did not intend to kill C?

Under the common law doctrine of transferred intent, a criminal defendant’s “evil intent” is transferred from the intended target to the unintended victim.

In recent times, some jurists have noted that the doctrine is an “unnecessary fallacy” since, at common law, malice aforethought meant the intent to kill anyone. See Ward v. State, 997 P.2d 528, 533 (Alaska App. 2000) (Mannheimer, J. concurring). Thus, when a defendant acted with malice aforethought, the defendant acted with the requisite mens rea regardless of who died. Alaska avoided this debate by expressly incorporating the concept directly into the statute; an intent to kill anyone satisfies the mens rea of murder. For this reason, transferred intent is rarely discussed in Alaska case law.

Figure 5.3 Murder in the First Degree – Transferred Intent

Even though the concept is easily understood when applied to a completed crime like first-degree murder, the concept is not easily understood when applied to an inchoate crime like attempted murder. Suppose that A deliberately shoots at B with the intent to kill B, but is a terrible shot, and hits C, severely injuring her. Although C survived the attack she will be disfigured for the rest of her life. Is A guilty of attempted murder?

Ramsey v. State, 56 P.3d 675 (Alaska App. 2002) answers this question. As you read the opinion, ask yourself whether the court reached the correct and just result.

Ramsey v. State, 56 P.3d 675 (Alaska App. 2002)

56 P.3d 675

Court of Appeals of Alaska.

Evan E. RAMSEY, Appellant,

v.

STATE of Alaska, Appellee.

No. A–7295.

Oct. 11, 2002.

OPINION

COATS, Chief Judge.

A jury convicted Evan Ramsey of two counts of murder in the first degree, one count of attempted murder in the first degree, and fifteen counts of assault in the third degree. Superior Court Judge Mark Wood sentenced Ramsey to a composite term of 210 years to serve. Ramsey appeals both his conviction and his sentence. We affirm in part and reverse in part.

On Wednesday morning, February 19, 1997, sixteen-year-old Evan Ramsey entered Bethel High School with a .12 gauge shotgun hidden under his jacket. Ramsey immediately walked toward the student common area where several students were sitting. At the nearest table sat Joshua Palacios, a fellow high school student, talking with several of his friends. Palacios began to turn around and stand up when Ramsey pulled out the shotgun and shot Palacios in the stomach. Palacios later died from his wounds. Two students who were sitting across from Palacios, S.M. and R.L., were also hit by pellets from the shotgun blast.

One of the art teachers at the high school, Reyne Athanas, was in the teacher’s lounge when she heard the first gunshot. She entered the hallway and observed Ramsey shooting into the ceiling. She saw Palacios lying on the floor with another student. During this episode, Ramsey paced up and down the hall several times in a very threatening manner. She and Robert Morris, another school teacher, attempted to convince Ramsey to put the shotgun down and give up. Ramsey then aimed the gun at them, but did not shoot. Ramsey walked away from Athanas and Morris, heading in the direction of the school’s main office where the school’s administrative offices were located.

Meanwhile, Ronald Edwards, the school principal, had been walking through the school looking for Ramsey because he had heard that Ramsey was in the school with a gun. Edwards found Ramsey as he was approaching the main office. Ramsey aimed the shotgun at Edwards, and Edwards turned around to run back into the school’s office. As Edwards was trying to get back into the office, Ramsey shot him in the back and shoulder. Edwards died in his office from the gunshot wounds.

Minutes after the shooting began, Bethel police officers arrived at the high school. Several officers entered the high school and saw Ramsey standing in the common area with the shotgun. Ramsey saw the officers and fired one round in their direction. After a brief exchange of gunfire, Ramsey put the shotgun down and gave up. According to the officers, as he threw the shotgun down, Ramsey yelled “I don’t want to die.” Officers were quickly able to detain Ramsey and take him into custody.

A grand jury indicted Ramsey on two counts of first-degree murder, three counts of attempted first-degree murder, and fifteen counts of third-degree assault. The State’s theory at trial was that Ramsey sought revenge against both Palacios and Edwards. The State introduced testimony that Ramsey and Palacios got into an argument and fight two years before the shooting. The State also introduced a letter found in Ramsey’s bedroom following the shooting that indicated Edwards was one of Ramsey’s intended victims. The letter read, in part,

Hi, everybody. I feel rejected. Rejected, not so much alone. But rejected. I feel this way because the day-to-day mental treatment I get usually isn’t positive. But the negative is like a cut, it doesn’t go away really fast, they kind of stick. I figure by the time you guys are reading this, I’ll probably have done what I told everybody I was going to do. Just hope a 12–gauge doesn’t kick too hard, but I do hope the shells hit more than one person, because I am angry at more than one person. One of the big assholes is Mr. Ed—Ron Edwards, he should be there. I was told that this would be his last year, but I know it will be his last year. The main reason that I did this is because I am sick and tired of being treated this way everyday. Who gives a fuck about it? Now, I got something to say to all of those people who think I’m strange can suck my dick and like it.

…

Life sucks in its own way, so I killed a little and kill myself. Jail isn’t for me ever and wasn’t.

Ramsey’s major defense at trial was that he was suicidal and did not form the requisite intent to commit first-degree murder or first-degree attempted murder. According to Ramsey, his intent during the shooting was not to kill anyone but merely to scare the people at the school and force the police to go to the high school and kill him. Ramsey’s counsel described Ramsey’s actions as “suicide-by-cop.”

The jury convicted Ramsey of two counts of first-degree murder, one count of first-degree attempted murder, and fifteen counts of third-degree assault. The jury also acquitted him of two counts of attempted first-degree murder and one count of third-degree assault. Judge Wood sentenced Ramsey to a composite term of 210 years’ imprisonment.

[…]

Did Judge Wood err in instructing the jury on the charge of attempted murder of S.M.

When Ramsey shot Palacios, S.M. and R.L., two students sitting across from Palacios, were also hit by pellets from the same shotgun blast. The State’s theory was that if Ramsey, with intent to kill Palacios, shot and injured S.M., he committed attempted murder in the first degree against S.M. Ramsey objected, contending that he could only be guilty of the attempted murder of S.M. if he had acted with the specific intent to kill S.M. Judge Wood disagreed and instructed the jury that:

In order to establish the crime of Attempted Murder in the First Degree as charged in Count III of the indictment, it is necessary for the state to prove beyond a reasonable doubt the following:

First, that the event in question occurred at or near Bethel … on or about February 19, 1997;

Second, that Evan Ramsey intended to commit the crime of Murder in the First Degree as to Count II [First–Degree Murder of Palacios] and;

Third, that the defendant shot S.M. with a firearm, which constituted a substantial step toward the commission of Murder in the First Degree.

Judge Wood allowed the State to argue in summation that if Ramsey had fired the shotgun at Palacios with the specific intent to kill him and had simultaneously injured S.M. (thereby taking a substantial step), Ramsey was guilty of attempted murder in the first degree of S.M. Judge Wood precluded Ramsey from arguing to the jury that the jury had to find that Ramsey had a specific intent to kill S.M. to find him guilty of the attempted murder of S.M. Ramsey contends that Judge Wood erred. We agree.

The parties point out that other jurisdictions that have addressed this or similar issues have reached entirely different results. Some jurisdictions hold that attempted murder is appropriately charged if the defendant’s actions killed the intended victim and also injured an unintended victim as a matter of public policy and deterrence. Other jurisdictions have held that attempted murder is an inappropriate charge under the theory that attempt, as an inchoate offense, requires the specific intent to kill a specific victim.

The doctrine of transferred intent arose in early common law to impute criminal liability to a person who, acting with the intent to harm, caused injury to an unintended victim. To avoid injustice, courts developed the theory of transferred intent, holding the individual responsible for the injury or death to the unintended victim. Most commentators, however, note that transferred intent is a misleading half-truth because at common law the requisite mental state was “malice aforethought,” which included the intent to kill anyone. These commentators note that the law, even at common law, did not require the ultimate person harmed be the intended victim.

The doctrine of transferred intent is unnecessary to ensure criminal liability under Alaska’s statute defining first-degree murder.

Alaska Statute 11.41.100 defines murder in the first degree as:

(1) with intent to cause the death of another person, the person (A) causes the death of any person. (emphasis added).

The plain language of AS 11.41.100 imputes criminal liability to anyone who, with the intent to cause death, causes death. The statute does not require the State to prove that a defendant had a specific intent to cause the death of a particular person to convict the defendant of murder. Therefore, under Alaska law, if a defendant acts with the intent to cause the death of another person, the defendant is guilty of murder for the death of any person whose death is caused by his act.

The question presented in this case is whether a similar rationale can be applied to attempted first-degree murder. To be guilty of attempted first-degree murder in Alaska, a person must (1) intend to cause the death of another, and (2) take a substantial step causing the death of any person. The State argues that Ramsey intended to cause the death of Palacios and that his wounding of Palacios was a substantial step towards causing S.M.’s death.

The problem with the State’s argument is that its logic leads to the conclusion that Ramsey could have been found guilty of the attempted murder of everyone in the school. The jury certainly found that Ramsey intended to cause the death of Palacios. And because his actions would have placed almost any reasonable person in the school in fear of serious physical injury, it is hard to say where the State’s attempted murder theory would stop. A defendant can be found guilty of attempted murder whether or not he actually injures his intended victim. Therefore, the State’s argument, carried to its logical extension, would allow it to convict Ramsey of the attempted murder of everyone in the building.

[…]

The jury found that Ramsey acted with intent to kill Palacios. Thus, his act of firing the shotgun at Palacios would constitute either attempted first-degree murder (if Palacios survived) or completed first-degree murder (if Palacios died). If, at the same time, Ramsey killed or injured one or more bystanders while he was trying to kill Palacios, Ramsey would be guilty of an additional crime for each of these bystanders—not an additional attempted murder, but rather an additional homicide if the bystander died or, if the bystander survived, either an attempted homicide or an assault, depending on Ramsey’s culpable mental state with regard to that bystander.

Here, under the jury instructions that embodied the State’s erroneous theory of attempted murder, the jury was asked to find whether Ramsey wounded S.M. while trying to kill Palacios. The jury so found. But the jury was not asked to decide other pertinent matters.

For instance, if Ramsey had intended to kill S.M. (in addition to Palacios), then Ramsey could properly be convicted of the attempted murder of S.M. (regardless of whether he injured S.M.). Even if Ramsey did not intend to kill S.M., if Ramsey inflicted serious physical injury on S.M., while trying to kill Palacios, he might properly be convicted of first-degree assault on S.M. Alternatively, if Ramsey merely inflicted physical injury on S.M. (while trying to kill Palacios), he might properly be convicted of second-degree assault on S.M.

Accordingly, we conclude that Judge Wood erred in instructing the jury and allowing the State to argue that it could convict Ramsey of attempted murder of S.M. if Ramsey intended to kill Palacios and simultaneously injured S.M. We conclude that the proper instruction would have required the jury to find Ramsey had the specific intent to kill S.M. before it could convict Ramsey of the attempted murder of S.M. Based on this rationale, Ramsey’s conviction for attempted murder in the first degree must be reversed.

[…]

Ramsey’s conviction for attempted murder in the first degree is REVERSED. His other convictions are AFFIRMED.

The More You Know . . .

Sadly, the Bethel High School shooting occurred long before similar incidents like Columbine, Sandy Hook, or Parkland. The circumstances surrounding mass shooting incidents (e.g., school shootings) have long been explored by researchers. According to a 2019 U.S. Secret Service analysis, all school shooting attackers between 2008 and 2017 exhibited concerning behaviors (engaged in behavior that caused fear, issued direct threats of violence, or brought weapons to school), most of whom communicated their intent to attack prior to the incident. For more information, see Protecting America’s Schools: A U.S. Secret Service analysis of targeted school violence. Washington, DC: Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Secret Service. (2019). Numerous states have implemented school safety tiplines in an effort to provide resources to alert authorities of disturbing behaviors before a mass shooting event occurs. See e.g., www.safeoregon.com or www.safeut.med.utah.edu. Some have had great success.

Heat of Passion

The law provides for a unique defense to intentional murder – heat of passion. Heat of passion is a killing that occurs during an extreme emotional state before the defendant has a reasonable time to calm down, provoked by the victim’s conduct. Historically, the defense was raised in cases involving adulterous murders. A defendant discovered their spouse in bed with a lover, and in an emotional rage, the defendant killed both spouse and lover. The common law recognized that such circumstances were likely isolated, mitigated, and deserving of a lesser punishment. This lesser punishment was referred to as the crime of “voluntary manslaughter” – a purposeful murder resulting from the victim’s serious provocation. The law recognized that the killing itself was unreasonable, but understandable.

Figure 5.4 Alaska Criminal Code – Defenses to Murder

![AS 11.41.115. Defenses to murder. In a prosecution under [intentional first-degree murder] or [intentional second-degree murder], it is a defense that the defendant acted in a heat of passion, before there had been a reasonable opportunity for the passion to cool, when the heat of passion resulted from a serious provocation by the intended victim. (b)-(f) [omitted for readability]](https://pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/2614/2022/09/HOP-diagram-300x169.jpg)

Heat of passion defense requires the killing to be in response to the victim’s serious provocation. If a victim “seriously provokes” a defendant, and the defendant kills the victim in an intense rage, the intentional murder is reduced to manslaughter. Thus, the heat of passion defense mitigates the seriousness of an intentional murder if the defendant unreasonably kills based on intense emotion. Heat of passion differs markedly from self-defense. Self-defense only justifies objectively reasonable killings, and it is a complete defense to the charge, resulting in an acquittal. Heat of passion mitigates unreasonable killings. See Ha v. State, 892 P.2d 184, 197 n.6 (Alaska App. 1995). Heat of passion is classified as an imperfect defense. A defendant acting under a heat of passion is partially excused of criminal liability. Instead of being guilty of intentional murder, the defendant is guilty of manslaughter.

The modern defense encompasses more than anger or rage; it includes fear, terror, and other intense emotions. This is not to say that a defendant’s “passion” is simply a subjective fear or anger. Instead, the defendant’s emotional condition – that is, the defendant’s response – must be reasonable, even though the killing itself is unreasonable. The trier of fact evaluates the existence (or non-existence) of serious provocation through the eyes of a reasonable (and sober) person standing in the defendant’s shoes.

Heat of passion is temporary. A defendant is only entitled to rely on heat of passion if they did not have a reasonable opportunity to cool. The next case, Luch v. State, 413 P.3d 1224 (Alaska App. 2018), focuses on the circumstances that may give rise to a valid heat of passion defense. As you read Luch, pay close attention to the source of the defendant’s belief of adultery.

Luch v. State, 413 P.3d 1224 (Alaska App. 2018).

413 P.3d 1224

Court of Appeals of Alaska.

Robert James LUCH, Appellant,

v.

STATE of Alaska, Appellee.

Court of Appeals No. A-11756

January 19, 2018

OPINION

Judge MANNHEIMER.

Robert James Luch was convicted of first-degree murder for shooting and killing his wife, Jocelyn. In this appeal, Luch argues that the trial judge committed error by failing to instruct the jury on the defense of heat of passion. […] For the reasons explained in this opinion, we conclude that … Luch’s [heat of passion] claim[] [has no] merit, and we therefore affirm his conviction.

Underlying facts

In the summer of 2010, Robert Luch and his family—his wife Jocelyn and their four children (Brent, Delia, Letitia, and Marcelyn)—moved back to Anchorage from their winter home in Arizona. One night in June, Luch awakened and noticed that the telephone was in use. When he picked up the receiver, Luch discovered that his wife Jocelyn was speaking with a man—Bryan Fuqua. Luch exchanged words with Fuqua. During their short but heated conversation, Fuqua indicated that his relationship with Jocelyn either was, or would shortly become, sexual. After hearing this, Luch hung up the phone. He woke up the children, and he angrily accused Jocelyn of having an affair.

During the next several months, the family lived in a state of uneasy tension. Luch and Jocelyn spoke little, and Jocelyn began staying out late, sometimes not coming home until the following day. The couple’s daughter Marcelyn later told the police that, during this period, Luch repeatedly threatened to kill both Jocelyn and the man he believed she was seeing.

In August, two of the Luchs’ children (Delia and Letitia) moved back to Arizona to attend college. This left four people in the Anchorage household: Luch, Jocelyn, and their children Marcelyn and Brent.

On September 17, 2010, Luch purchased a handgun, purportedly for protection at the family cabin near Sutton. Luch did not inform Jocelyn of this purchase; the only other family member who knew about the gun was Luch’s son Brent.

Eleven days later, on the morning of September 28, 2010, Luch learned that a car he had loaned to his daughter Delia had been impounded in Arizona. Luch was incensed, and he began yelling at Delia on the telephone. Brent overheard this conversation and tried to calm things down, but Luch turned on Brent, and a fist fight ensued. Luch’s daughter Marcelyn eventually intervened and stopped the fight, but Luch was still angry.

Luch then drove to the hotel where his wife Jocelyn worked and tried to see her, purportedly so that he could tell her about the impoundment of Delia’s car and his fight with Brent. When Jocelyn could not leave her work station immediately, Luch parked his vehicle behind the hotel and waited for several hours, becoming angrier as time passed. Eventually, Luch drove home without Jocelyn, and Brent and Marcelyn later picked Jocelyn up.

That same night, Marcelyn and Jocelyn were scheduled to run in a race held at Kincaid Park. A friend of Jocelyn’s, a runner named Steve Crook, came to pick them up. At the last minute, Marcelyn decided not to go.

When Luch learned that Marcelyn had not accompanied Jocelyn to the race, he insisted that Marcelyn go with him to Kincaid Park to confirm that Jocelyn was actually at the race. At the park, they stood near the finish line and watched as hundreds of racers crossed the finish line, but they did not see Jocelyn.

Once the race was over, Marcelyn called Jocelyn on her cell phone. Jocelyn said that she was at a nearby bunker. (Kincaid Park was built on the site of a former missile installation.) Marcelyn suggested to Luch that he drive to the bunker while she walked over there and found Jocelyn. But as Marcelyn was walking toward the bunker, Jocelyn spoke to her again on the phone: Jocelyn corrected herself and said that she was not at the bunker, but rather at the adjacent Kincaid chalet. Marcelyn was unable to inform Luch of this new information because she (Marcelyn) had his cell phone.

Marcelyn went to the chalet and found her mother, but Luch did not arrive to pick them up. Luch had apparently driven around the Kincaid parking lot, honking repeatedly and becoming increasingly agitated, until finally he drove home alone.

When Jocelyn and Marcelyn realized that Luch was not coming for them, Marcelyn called her brother Brent, who came and picked them up.

When Jocelyn and the children arrived home, Luch was sitting in his recliner in the downstairs living room. He repeatedly accused Jocelyn of not having run the race.

Brent and Marcelyn soon went to their bedrooms upstairs. Jocelyn also went upstairs and began preparing for bed. Luch came upstairs and confronted her—accusing her of lying about participating in the race, and accusing her of seeing another man. Jocelyn assured Luch that she had been at the race, and she denied any wrongdoing, but Luch was not convinced. He went downstairs to the garage, where he retrieved the newly purchased handgun from a locked storage room. He then went back upstairs.

According to Luch’s testimony at trial, he did not retrieve the gun with the intent of harming his wife. Rather, Luch told the jury that he intended to use the gun “to posture, to stage.” Luch testified that, by simply displaying the gun to Jocelyn, he hoped to convince her that he was willing to shoot any man she was seeing, so that she would then “relay a message” to this man.

By the time Luch returned upstairs, Jocelyn had gone into the bathroom. Luch followed her there. Shortly thereafter, Marcelyn heard Jocelyn say, “Don’t push me”—and then she heard two gunshots. Marcelyn and Brent rushed into the hallway, and Marcelyn saw Luch leave the bathroom and go downstairs carrying the handgun. Luch said nothing to his children.

The children had to force their way into the bathroom because Jocelyn’s body was blocking the door. Jocelyn was still alive, but she was bleeding from two gunshot wounds. Brent located Jocelyn’s cell phone and called 911.

The police arrived within minutes. Anchorage Police Officer Mark Bakken entered the house and stayed with Jocelyn until an ambulance arrived. During that brief conversation, Jocelyn told the officer that Luch had shot her because she wanted to divorce him and she refused to return to Arizona with him.

While this was happening, Luch took the handgun back to the storage room of the garage, and he then left the house. The police found Luch walking down the street. Luch told them, “I’m the one you want.”

Jocelyn was taken to the hospital, but she died from her wounds. Luch was indicted for this homicide under alternative theories of first- and second-degree murder.

Luch’s claim that he was entitled to a jury instruction on the defense of heat of passion

Luch contends that the trial judge committed error by rejecting his attorney’s request for a jury instruction on the defense of “heat of passion”. We will first describe the law in Alaska regarding heat of passion, and then we will explain why Luch was not entitled to a jury instruction on this defense.

(a) Explanation of the defense of heat of passion under Alaska law

The defense of heat of passion is defined in AS 11.41.115. This statute declares that heat of passion is a partial defense to two types of murder:

-

- a homicide charged under AS 11.41.100(a)(1)(A)—i.e., an intentional killing that would otherwise be first-degree murder, or

- a homicide charged under AS 11.41.110(a)(1)—i.e., a killing that would otherwise be second-degree murder because it resulted from an assault where the defendant intended to inflict serious physical injury, or where the defendant knew that the assault was substantially certain to cause death or serious physical injury.

The defense of heat of passion applies to instances where the defendant “acted in a heat of passion … result[ing] from a serious provocation by the intended victim”, and where the defendant assaulted the victim “before there [was] a reasonable opportunity for the passion to cool”. AS 11.41.115(a).

For purposes of the heat of passion defense, the term “serious provocation” is defined to mean “conduct … sufficient to excite an intense passion in a reasonable [and unintoxicated] person in the defendant’s situation, … under the circumstances as the defendant reasonably believed them to be”. AS 11.41.115(f)(2). However, the statute limits the scope of “serious provocation” by adding that “insulting words, insulting gestures, or hearsay reports of conduct engaged in by the intended victim do not, alone or in combination with each other, constitute serious provocation.” Ibid.

Although heat of passion is a defense to first-degree murder charged under AS 11.41.100(a)(1)(A) or second-degree murder charged under AS 11.41.110(a)(1), it is only a partial defense. Heat of passion does not exonerate the defendant; instead, it reduces the crime to manslaughter. See AS 11.41.115(e).

[…]

(b) There was insufficient evidence that Luch was subjected to a “serious provocation” within the meaning of the heat of passion statute

A defendant is entitled to have the jury instructed on a defense if the defendant presents “some evidence” of that defense. In this context, the phrase “some evidence” is a term of art. It means evidence which, if viewed in the light most favorable to the defendant, is sufficient to allow a reasonable juror to find in the defendant’s favor on every element of the defense.

As we explained in the preceding section of this opinion, the elements of the defense of heat of passion are (1) that Luch shot his wife “in a heat of passion”, (2) that this passion was the result of a “serious provocation” (as that phrase is defined in the statute), and (3) that Luch shot his wife before there was a reasonable opportunity for his passion to cool.

Even when the evidence in this case is viewed in the light most favorable to Luch’s proposed defense, there was insufficient evidence that Luch was subjected to a “serious provocation”.

The governing statute, AS 11.41.115(f)(2), defines “serious provocation” as “conduct … sufficient to excite an intense passion in a reasonable [and unintoxicated] person in the defendant’s situation, … under the circumstances as the defendant reasonably believed them to be”. Here, the alleged “serious provocation” was the purported fact that Luch’s wife was having an affair.

As we explained earlier in this opinion, there was evidence that, several months before the shooting, Luch learned that his wife might have been having an affair—in particular, the testimony about the overheard phone call, and about Jocelyn’s refusal to explain why she was spending several nights a week away from the marital home.

But in Luch’s trial testimony, he conceded that his relationship with his wife was significantly better in the two months immediately preceding the shooting. And there was no evidence that Luch knew or even reasonably believed at the time of the shooting that Jocelyn was having an affair. There was plenty of evidence that Luch suspected that his wife was having an affair at that time, but even Luch conceded in his trial testimony that he did not know whether his suspicions were well-founded.

At trial, Luch’s attorney asked him whether his suspicions intensified on the day of the killing (September 28, 2010), after Luch went to pick up Jocelyn from work and ultimately left without her. Luch’s attorney asked him, “At [that] point, are you thinking she’s cheating?”, Luch responded:

Possibly. I—I don’t want to believe that. I want to trust my wife very badly. … I want to believe the best scenario, so I’m trying to resist going that direction in my thought. But there’s, of course, there’s a, there’s some doubts. I’m not sure.

Later that day, after the incident in Kincaid Park where Luch was unable to locate Jocelyn at the race, Luch was waiting at home when Jocelyn and the children (Marcelyn and Brent) arrived home from Kincaid Park. According to Luch, he was “festering” because he strongly suspected that his wife had not run the race at Kincaid Park—that she was “off on another tryst”. But Luch added that he was not sure about this. He explained that he was “trying to hold it all together” because “there might be something [he was] not aware of”—for instance, the possibility of “a mechanical breakdown”, or a “different finish line” to the race.

When Jocelyn got home, Luch repeatedly accused her of not having run in the race. But Jocelyn did not respond to these accusations; instead, she went upstairs after a few minutes and started preparing for bed. Luch followed her upstairs and confronted her—accusing her of lying about participating in the race, and accusing her of seeing another man. Jocelyn assured Luch that she had been at the race, and she denied any wrongdoing, but Luch was not convinced. At that point, Luch went to the garage, obtained the handgun, and returned to his wife’s bathroom.

At common law, one classic example of “serious provocation” was the defendant’s discovery of their spouse’s adultery. However, the common law required that the defendant find their spouse in flagrante delicto—that is, in the very act of committing adultery. Reflecting this principle, Alaska’s statutory definition of “serious provocation”, AS 11.41.115(f)(2), expressly declares that a “serious provocation” cannot be based on hearsay reports.

Thus, when a defendant claims that they committed a deadly assault in response to a discovery of adultery, that “discovery” must be based on the defendant’s personal knowledge, and not the defendant’s suspicions or conclusions based on hearsay accounts (which are expressly excluded by the statute).

The fact that, several months before the shooting, Luch may have had good reason to believe that Jocelyn was having an affair does not mean that Luch was experiencing a “serious provocation” when, on the day of the race, he could not find Jocelyn where he expected her to be. Luch never claimed that he had personal knowledge of his wife’s adultery, and there was no evidence that Jocelyn admitted adultery to him. In fact, the evidence was that Jocelyn denied any wrongdoing when Luch confronted her on the day of the killing.

Nor was there evidence that Luch reasonably believed that Jocelyn was committing adultery. Although Luch repeatedly expressed suspicions that his wife was having an affair, he conceded on the stand that his doubts about his wife’s fidelity were unconfirmed, and that he knew there were other potential explanations for his failure to see Jocelyn at the finish line of the race at Kincaid Park.

We therefore hold that Luch failed to present some evidence that he was subjected to a “serious provocation” as that term is defined in AS 11.41.115(f)(2). Because of this, we affirm the trial judge’s decision not to instruct the jury on the defense of heat of passion.

[…]

Conclusion

The judgement of the superior court is AFFIRMED.

The trier of fact must assess the circumstances the defendant faced from the perspective of a “reasonable person.” A reasonable person means a reasonable, mentally healthy person whose cognitive abilities are not influenced by mental difficulties, such as a head injury, intoxication, or cultural background. Provocation is measured from an ordinary person’s perspective, which causes the person to lose their normal self-control. Also, the victim’s conduct that gives rise to serious provocation must be based on information that the defendant knows. It may not be based on information that the defendant heard or suspects is true.

Second-Degree Murder

Second-degree murder is non-intentional murder. Generally speaking, second-degree murder encompasses implied malice murders, such as murder committed with the intent to inflict serious physical injury or extreme reckless killings. In Alaska, a person can commit second-degree murder in six separate ways, but all expressly exclude murder with the intent to kill. Instead, second-degree murder includes circumstances where the defendant intends to cause serious injury but causes death, death caused under circumstances manifesting an extreme indifference to human life, or commits felony murder, including when the defendant traffics in dangerous drugs and a person dies as a result of ingesting the substance.

Figure 5.5 Alaska Criminal Code – Murder in the Second Degree

![AS 11.41.110. Murder in the second degree. (a) A person commits the crime of murder in the second degree if (1) with intent to cause serious physical injury to another person or knowing that the conduct is substantially certain to cause death or serious physical injury to another person, the person causes the death of any person; (2) the person knowingly engages in conduct that results in the death of another person under circumstances manifesting an extreme indifference to the value of human life; (3) [Felony-Murder] (4)– (5) [omitted for readability]](https://pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/2614/2021/07/11.41.110-diagram-M2-v2-300x169.jpg)

Notice that subsection (a)(1) embodies two separate theories of second-degree murder. The first clause – the “serious-physical-injury theory” – requires the defendant to intend to cause serious physical injury to the victim and cause death. We will explore serious physical injury in more detail in the next chapter, but generally, serious physical injury includes any significant injury. “Intent-to-maim” murders fall within this category. For example, a jury could infer that a defendant who stabs their victim eight times in the leg had a conscious objective to cause serious injury to the victim. Should the victim die as a result of the stabbing, the defendant would be guilty of second-degree murder under the “serious-physical-injury theory”. AS 11.41.110(a)(1).

The second clause defines second-degree murder as knowingly engaging in conduct that “is substantially certain to cause death or serious physical injury to another person.” AS 11.41.110(a)(1). This type of murder requires more than reckless conduct. The defendant must be substantially aware that his conduct would result in the victim’s death or serious physical injury. See e.g., Morrell v. State, 216 P.3d 574, 577 (Alaska App. 2009). “Shooting into a crowded room without an intent to cause death or serious physical injury” would be an example of the type of conduct that would be punishable under the second clause of subsection (a)(1). See legislative commentary, 1978 Senate Journal Supp. No. 47, at 10.

Subsection (a)(2) criminalizes extreme reckless murders. Extreme recklessness is a non-codified culpable mental state that requires the jury to determine whether the defendant caused the death under circumstances that created an extreme indifference to the value of human life. This phrase – extreme indifference to the value of human life – is nebulous by design. In answering this question, the trier of fact (e.g., the jury) is obligated to balance four factors:

- the social utility of the defendant’s conduct;

- the magnitude of the risk the defendant’s conduct created, including both the nature of the harm that was foreseeable by the defendant and the likelihood that the defendant’s conduct would cause that harm;

- the defendant’s knowledge of the risk; and

- any precautions the defendant took to minimize the risk.

See generally Neitzel v. State, 655 P.2d 325, 337 (Alaska App. 1982).

The mental state requires the jury to assess the level of recklessness of the defendant’s conduct. The jury must weigh the social utility of the defendant’s conduct (if any) against the precaution the defendant took to minimize the apparent risks. Recall that playing “Russian Roulette,” is incredibly dangerous and completely lacks any social utility, but shooting in the direction of a victim of a bear attack may demonstrate some social utility despite the magnitude of the risk. See id. As always, whether a particular act constitutes extreme recklessness is a question of fact for the jury.

Felony murder, given its unique history and application will be discussed separately in the next section.

Even though second-degree murder is not as “serious” as intentional murder, it remains an unclassified felony offense with a sentencing range of 20 to 99 years imprisonment. Although the mandatory minimum sentence for second-degree murder (20 years) is less than first-degree murder (30 years).

Exercises

Answer the following questions. Check your answers using the answer key at the end of the chapter.

- Jay is angry about the grade he received on his criminal law midterm. Jay pulls a loaded revolver out of his backpack, aims at a tree and fires in an attempt to release his frustrations. Unfortunately, Jay is an inexperienced marksman and the bullet strikes an innocent bystander in the forehead, killing him. What was Jay’s criminal intent when shooting the revolver?

- Johnnie decides he wants to kill Marcus, the leader of a rival gang. Johnnie knows that Marcus always hangs out in front of the gas station on Friday nights. Johnnie puts his gun in the glove compartment of his car and drives to the gas station on a Friday night. He sees Marcus standing out front. He slowly drives by, takes aim, and shoots Marcus from the car, killing him. Could this be first-degree murder? Explain your answer.