Other Use-of-Force Justification Defenses

Self-defense is not the only use of force justification. A person is legally justified in using force to defend another person, recapture certain property, and protect one’s home (habitation). Also, certain individuals, like police officers, are legally justified in using both nondeadly and deadly force under circumstances that an ordinary citizen may not due to their official position. Specifically, police officers are authorized to use force to make an arrest, stop individuals who are committing crimes, or capture escapees. In Alaska, each of these scenarios acts as a perfect defense – that is, the individual is free from any criminal liability (although the person may face civil liability). Heat-of-passion, a use of force defense based on provocation, operates as an imperfect defense and will be explored in the next chapter.

Defense of Others

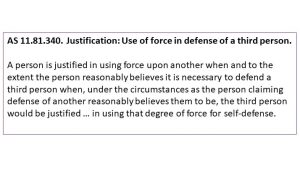

At common law, a defendant could use force to defend another if the defender had a personal relationship with the other person, such as a family connection. See Wayne R. LaFave, Substantive Criminal Law §10.5(a) (3rd ed. 2018). Nearly all jurisdictions have rejected such a narrow rule. Under modern criminal codes, including Alaska, a person may defend anyone to the same degree that he or she could use self-defense. AS 11.81.340. With one exception, defense of others requires the same elements as self-defense: the individual defended must be facing an unprovoked, imminent attack and the defendant must use a proportional degree of force with a reasonable belief that the force is necessary to repel the attacker.

Figure 14.3 AS 11.81.340. Justification: Use of force in defense of a third person.

Occasionally, a person will use force to defend another who has no legal right to use force in self-defense. Under such a scenario, a defendant may use force to defend another person if it reasonably appears that the use of force is justified under the circumstances. See David v. State, 698 P.2d 1233, 1235 (Alaska App. 1985). If a person has a reasonable, subjective belief that the individual needing protection could use force themselves, the defense of others doctrine authorizes the person to use force.

Example of Defense of Others

Alex and Shane are aspiring WWE professional wrestlers and are training in a rural field outside of Wasilla. Alex pretends to attack Shane, aggressively “kicking” him while he is on the ground. Of course, Alex does not strike Shane with any force. It is all an act. Timmy, who is jogging in the area, dashes over and begins beating Alex. Although Timmy misinterpreted the circumstances, he is likely entitled to claim the defense of others justification because it reasonably appeared that Alex was unlawfully attacking Shane. Since Timmy honestly believed Shane had the right to self-defense in this situation, Timmy has a justification defense.

Defense of Property

Individuals may use force to defend property under limited, specified circumstances.

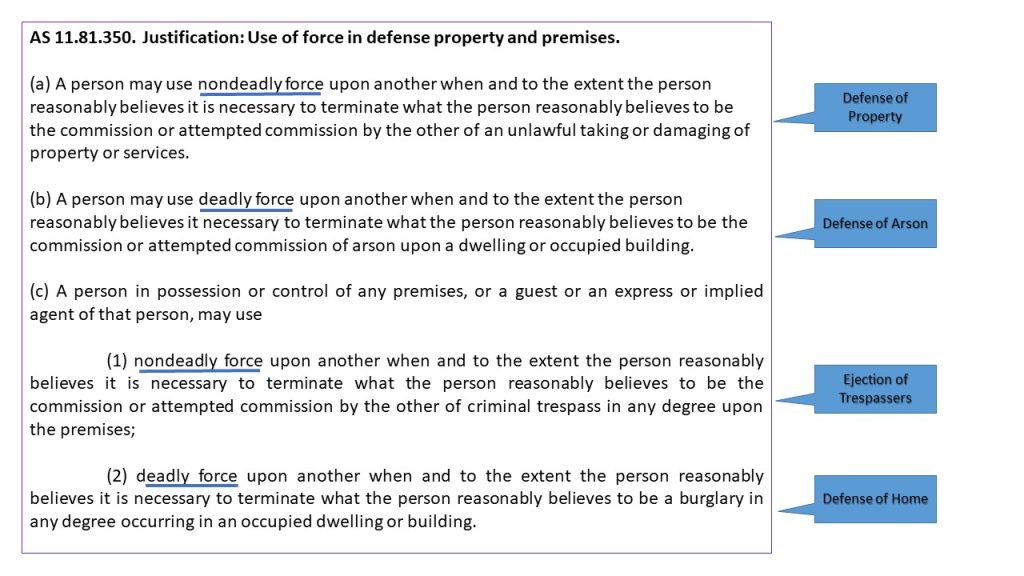

The general principle of necessity applies. A person may use nondeadly force upon another person when the person reasonably believes that the other person is unlawfully taking or damaging property. AS 11.81.350(a). Generally, the defendant must have an objective, reasonable belief of an imminent threat of theft, damage, or destruction. The right to use force to defend or reclaim property only applies when the damage or theft is “about to be committed or is actually being committed.” See Woodward v. State, 855 P.2d 423, 428 n.14 (Alaska App. 1993). Alaska has adopted the “traditional view that a theft victim is allowed to use force to recapture property only if the victim acted immediately after the dispossession of property or upon hot pursuit.” See Kone v. State, 2018 WL 573339 (Alaska App. 2018). Thus, a defendant can chase someone who steals personal property and take the item back, but the chase must be immediate. Delay extinguishes the defense.

The force used must also be objectively reasonable. A defendant may only use reasonable force to protect property. (A defendant may also use reasonable force to prevent a theft of services, although such events are rare.) A defendant may not use deadly force to reclaim personal property or prevent damage to property. Except in the narrow situations discussed shortly, deadly force is never appropriate when defending property.

Property can be real, personal, or intangible. Real property is land and anything permanently attached to it. Personal property is any tangible, movable object. Intangible property includes personal services.

Example of Defense of Property

Jack and Martha are sitting on a park bench enjoying the Alaska summer when Sam runs by and grabs Jack’s briefcase. Martha chases Sam down, tackles him, and recovers the briefcase. Sam suffers several abrasions during Martha’s tackle. Martha will be able to rely on the defense of property as a defense to misdemeanor assault (i.e., recklessly causing injury to Sam) since it is clear that Martha believed that force was immediately necessary to recapture Jack’s briefcase.

Ejection of Trespassers

A trespasser is an individual who enters or remains unlawfully on another person’s property. AS 11.46.320-30. Property owners, authorized agents, and guests have a legal right to eject trespassers using nondeadly force. AS 11.81.330(b)(1). The amount of force must be reasonable; deadly force is never reasonable to eject a trespasser unless the trespasser threatens imminent deadly force against the ejector or third person. In such a scenario, traditional rules of self-defense govern. Put another way, deadly force may be justified by self-defense or defense of others, but never under the need to eject a trespasser.

Deadly Force – Defense of Home / Defense of Arson

But for two exceptions, deadly force is never permitted to defend property. The law holds life paramount. That said, deadly force is permitted when defending one’s home from intruders or defending one’s home from arsonists. Take note, however, that both of these exceptions are not necessarily “defense of property” justifications, but are really defense of person justifications.

At early common law, a person’s home was his castle, and the law authorized the use of deadly force to defend it. This was commonly referred to as the “castle doctrine.” Alaska, like most states, has largely incorporated the castle doctrine into the criminal code. A person may use deadly force when the person reasonably believes it is necessary to terminate either: (1) an arson of an occupied building, or (2) a burglary of an occupied building. AS 11.81.350. Thus, the law specifically allows a person to use deadly force to protect the occupants of a building from burglary or arson. Like with other self-defense situations, a person defending a home need not retreat prior to using deadly force. AS 11.81.350(f).

The law contains an important caveat – it only applies to an “occupied” dwelling or building. Deadly force is not permitted to defend unoccupied structures. Thus, a person may not use deadly force to terminate a burglary of an unoccupied residence. Likewise, a person may not use deadly force to stop an arsonist from starting a fire in an abandoned warehouse. Put another way, the law allows deadly force in situations where it is likely necessary to protect the people inside the building. Since the building must be occupied, the use of spring-guns or other lethal defense weapons designed to protect unoccupied dwellings is not permitted.

Figure 14.4 AS 11.81.350. Justification: Use of force in defense of property and premises.

Example of Defense of Home under the Castle Doctrine

Nate, a homeowner with three children, hears the side door open in the middle of the night. Nate removes a handgun from the nightstand and creeps silently down the stairs. Nate sees a male figure tiptoeing towards his daughter’s bedroom. Nate shoots and kills the person. The person turns out to be Bobby, Nate’s daughter’s boyfriend, who was trying to sneak into her bedroom at her request. Nate is not likely guilty of murder under the defense of home. Bobby made entry into an occupied residence. It is difficult to identify individuals in the dark and ascertain their motives and it was objectively reasonable to believe that Nate felt threatened by Bobby’s presence in the home.

Carjacking

Similar to the right to defend an occupied building from an intruder with deadly force, the law also permits a person to use deadly force to stop a “carjacking.” AS 11.81.350(d). This specific provision is largely superfluous. Carjacking is not a crime under Alaska law, but robbery of an occupied vehicle is. Just as a person would be entitled to use deadly force to prevent any robbery, the law permits a person to use deadly force to stop a vehicle robbery – also known as a “carjacking”.

Execution of Public Duties

Public servants are frequently called upon to use force in the performance of their duties. Police officers use force when arresting suspects, emergency personnel use force when providing emergency services, and prison guards use force when detaining prisoners. Such intrusions to a person’s liberty would ordinarily constitute a violation of criminal law, namely assault. But the law permits public servants (and private persons assisting public servants) to use reasonable force under the execution of public duties justification. While the law allows most public servants to use force when necessary, police officers are the most frequently scrutinized. Law enforcement routinely use force during lawful investigative stops, suspect apprehension, or recapturing escapees. Police officers are justified in using force in situations that an ordinary citizen would be prohibited.

Use of Force in Arrest and Apprehension of Criminal Suspects

As you have read, the crux of all use of force justifications is reasonableness. The law requires all individuals to act reasonably when using force. Law enforcement officers are no different. Yet even though officers must act reasonably, police officers’ use of force requires the balancing of two competing interests not found in ordinary citizen situations. On one hand, law enforcement have sworn a duty to uphold the law and keep the public safe. The public demands that police enforce criminal laws – especially serious ones. Society has authorized officers to use force in the performance of this duty. On the other hand, individuals have a cognizable interest to be free from unreasonable government harm. Excessive force is never allowed, and police officers who use excessive force can face criminal sanctions.

In a series of judicial opinions, the US Supreme Court recognized the difficulty of this balance and clarified that the Fourth Amendment governs constitutional torts arising from law enforcement’s use of force. The Fourth Amendment protects all citizens from “unreasonable searches and seizure.” U.S. Const. amend. IV. Although the Fourth Amendment implicates criminal procedure, and not substantive criminal law, an officer’s use of force constitutes a seizure, and the Fourth Amendment requires police actions to be objectively reasonable. This was a significant departure from common law and was important to the understanding of police use of force.

In Tennessee v. Garner, 417 U.S. 1 (1985), an unarmed fleeing burglar was shot in the back. The involved officer admitted that he was reasonably sure that the suspect was unarmed, but nonetheless, he used deadly force under the common law fleeing felon rule, which authorized police to use deadly force to apprehend a felon fleeing from the police irrespective of whether the felon was armed or otherwise dangerous. (Tennessee had codified the rule in statute.) The Court found the fleeing felon rule (and Tennesse’s statute) unconstitutional. The Court held that law enforcement may only use deadly force against a fleeing suspect when the officer has probable cause to believe that the suspect poses a significant threat of death or serious physical injury to the officer or others. The mere belief that the suspect committed a serious crime is insufficient. Since the use of deadly force is the ultimate seizure, law enforcement must act reasonably in using it.

Nondeadly force is no different. In Graham v. Connor, 490 U.S. 386 (1989), the Court held that the use of nondeadly force must also be analyzed under the Fourth Amendment. Objective reasonableness requires the trier-of-fact to consider the circumstances confronting the officer at the time force was used. This determination is not made with the “20/20 vision of hindsight.” See id. In other words, when determining whether an officer’s use of force was reasonable, the situation has to be viewed at the precise moment the force was deployed. The fact that officers could have done something different to avoid the use of force is irrelevant. Instead, the question is whether a reasonable officer, faced with the same circumstances, would have believed that the degree of force was necessary. Jones-Nelson v. State, from the previous section, is largely in accord with this principle.

Alaska’s statutory use of force justification for police officers largely codifies this rule. Police officers are entitled to use nondeadly force, and threaten the use of deadly force, when apprehending a criminal suspect. AS 11.81.370(a). It is for this reason that police officers may draw their weapons during an arrest. Officers may also use nondeadly force when conducting investigative stops and recapturing escapees. Investigative stops are beyond the scope of this text, but generally speaking, an investigative stop occurs when the officer has a reasonable suspicion that criminal activity is afoot. Coleman v. State, 553 P.2d 40, 46 (Alaska 1976).

An officer’s use of deadly force is much more limited. An officer may use deadly force when the officer reasonably believes (1) the suspect has committed, or attempted to commit, a violent felony, (2) the suspect has escaped and is armed with a firearm, or (3) the suspect is engaging in highly dangerous behavior and must be immediately arrested to prevent death or serious injury. AS 11.81.370.

The authorizations to use force in this final paragraph are in addition to the justification ordinary citizens have. The circumstances presented here are the extraordinary circumstances that an officer may face that an ordinary citizen may not. But remember, a police officer, like any person, has the right to use deadly force to defend herself against a threat of imminent serious physical injury or death to herself or others. Thus, if an officer uses force to defend herself or a third person, their conduct is analyzed under self-defense or defense of others.

Unreasonable Force by Law Enforcement During an Arrest

In 2014, Bethel Police Officer Andrew Reid responded to a report of an intoxicated man in the parking lot of the local grocery store. Officer Reid found Wassillie Gregory lying in the middle of the parking lot. When Officer Reid began to take Gregory into custody, Gregory refused to comply – Gregory passively tucked his hands under his body to prevent Officer Reid’s attempted use of handcuffs. In response, Officer Reid repeatedly slammed Gregory into the ground and used pepper spray until Gregory complied. Gregory dislocated his shoulder that eventually needed surgery to correct it. The incident was captured on the store’s surveillance camera. Officer Reid was charged and convicted of misdemeanor assault because the amount of force used – admittedly nondeadly – was not objectively reasonable or necessary. Officer Reid was not justified in using the level of force in arresting Gregory; it was excessive.

Assessment of Criminal, Not Civil, Liability.

Finally, recall that this section addresses situations where a police officer has used force against a person and faces criminal liability. Although questions of civil liability frequently overlap when discussing law enforcement excessive force issues, the justifications discussed here focus on criminal behavior.

Like all criminal behavior, the ultimate charging decision rests with the prosecutor. Because of the level of scrutiny that occurs when an officer uses deadly force, the Alaska Attorney General’s Office reviews all deadly force incidents to determine if the officer was legally justified in using deadly force and whether the officer should be criminally charged with a crime. The Attorney General’s role in these cases is unique. Although the Alaska Attorney General has a duty to prosecute all violations of criminal law, the Attorney General’s Office is not an investigatory agency. AS 44.23.020(b)(2). It relies on the criminal investigation conducted by the involved agency or a sister agency. The Attorney General’s Office does not conduct its own investigation. Further, Alaska law enforcement agencies have no legal requirement to report the use of force – deadly or otherwise – to the Attorney General for review. Instead, most law enforcement agencies have adopted a policy to refer officer-involved deadly force incidents to the Attorney General for review.

Special Relationships

There are several situations when a person may use nondeadly force based on a special relationship. AS 11.81.430. For example, the law specifically authorizes parental and school corporal punishment. Parents and guardians are permitted to use nondeadly force when reasonably necessary to promote the welfare of the minor. School administrators (principals, teachers, etc.) are entitled to use nondeadly force to enforce school rules. Common carriers may use force against passengers to maintain order. A person may also use nondeadly force to prevent a suicide. Finally, medical professionals may use nondeadly force when providing medical treatment. Deadly force is never permitted.

Exercises

Answer the following questions. Check your answer using the answer key at the end of the chapter.

- Melanie watches as Betty verbally abuses Colleen. Betty is a known bully who verbally abused Melanie in the past. Betty calls Colleen an expletive and gives her a firm shove. Melanie walks up behind Betty, removes a knife from her pocket, and plunges the knife into Betty’s back. Betty suffers internal injuries and later dies. Can Melanie use the defense of others as a defense to murder? Why or why not?

- Officer Use of Force, Recommended Listening: Listen to the podcast episode “Graham” from Radiolab©. As you listen to the episode reflect on the impact of the reasonable officer standard for purposes of holding police officers accountable and whether police accountability is achievable under the current system. The episode and transcript can be found at https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/radiolab/articles/graham. As you listen, keep in mind that both Garner and Graham address the appropriate legal standard for use in the federal civil rights statute (42 USC § 1983), not the legal standard for use in a criminal statute. However, as you have seen, this standard has been largely incorporated into Alaska law. See e.g. C. Flanders & J. Welling, Police Use of Deadly Force: State Statutes 30 Years After Garner, 35 St. Louis U. Pub. L. Rev. 109 (2015).