Robbery, Extortion, and Coercion

Robbery is the forcible taking of property from another. At common law, robbery was considered an aggravated theft crime. Modern criminal codes treat robbery as a crime of violence. Alaska has adopted this view. Robbery is neither a crime against property, nor an aggravated theft. Robbery is a crime of violence. It protects innocent persons from physical harm – the same societal interests as assault. See Marker v. State, 692 P.2d 977 (Alaska App. 1984). Recall that robbery is an inherently dangerous felony under the felony murder rule for second-degree murder. AS 11.41.110(a)(2).

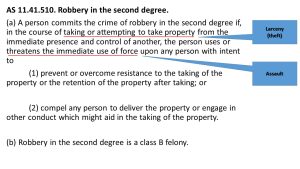

In Alaska, robbery is classified as either first- or second-degree robbery. Second-degree robbery contains the basic elements of the crime; the crime is elevated to first-degree robbery if certain special circumstances (aggravating factors) are present.

Figure 6.9 Alaska Criminal Code – Second-Degree Robbery

Example of Second-Degree Robbery

Collins decides he needs money, but does not want to hurt anyone. Collins decides to take money from the local tanning salon. Collins enters the tanning salon around 10:00 in the evening, just before the salon’s closing time. At that time, there was one employee on duty: a young woman named Tammy. Collins poses as a potential customer and asks Tammy to show him around the facility. She does so, and then Collins leaves. A little later, the salon’s last customer leaves. Soon thereafter, Collins re-enters the salon. He immediately walks behind the service counter and stands next to Tammy. Collins forces T.M.’s hands down on the counter. At the same time, Collins calmly asks Tammy where the money is. Tammy opens the cash register. Collins takes the money and leaves.

Under this scenario, Collins has likely committed the crime of second-degree robbery. Collins used force against Tammy when he took control of her hands. See e.g., Collins v. State, 2018 WL 2363462 (Alaska App. 2018).

First-degree robbery requires special circumstances to be present – such as the defendant being armed with a weapon or causing serious physical injury during the robbery. Note that the defendant need not actually be armed. First-degree robbery also encompasses the representation that the defendant is armed. Thus, all “armed” robberies – regardless of whether the defendant actually possessed a weapon – constitute first-degree robbery. The robbery statute focuses on the dangers associated with the use (or threat) of force during the theft.

Figure 6.10 Alaska Criminal Code – First-Degree Robbery

![AS 11.41.500. Robbery in the first degree (a) A person commits the crime of robbery in the first degree if the person violates [second-degree robbery] and, in the course of violating that section or in immediate flight thereafter, that person or another participant (1) is armed with a deadly weapon or represents by words or other conduct that either that person or another participant is so armed; (2) uses or attempts to use a dangerous instrument or a defensive weapon or represents by words or other conduct that either that person or another participant is armed with a dangerous instrument or a defensive weapon; or (3) causes or attempts to cause serious physical injury to any person. (b) Robbery in the first degree is a class A felony.](https://pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/2614/2022/09/Robbery1-Diagram-300x169.jpg)

Unsuccessful Robberies

Although we generally focus on successful robberies, a defendant need not be successful to be guilty of robbery. A defendant can be convicted of robbery even if it turns out that, unbeknownst to the defendant, the victim had an “empty pocket” – that is, the victim did not possess the property being sought. The robbery statutes criminalize unsuccessful attempts to take property to the same extent as successful takings. That is not to say a defendant cannot also commit the crime of attempted robbery, but once the defendant uses force, a completed robbery has occurred, regardless of whether the taking was successful. See Beatty v. State, 52 P.3d 752 (Alaska App. 2002). A defendant commits attempted robbery if the defendant takes a substantial step towards the commission of the offense, but prior to the use of force.

Finally, the force used need not be directed at the property owner. A robbery is committed, not only when the defendant uses force upon the person who possesses the property, but whenever a defendant uses force upon any person with the intent to accomplish the theft. See McGrew v. State, 872 P.2d 625 (Alaska App. 1994). For example, if a couple is “mugged” in a dark alley, the defendant is guilty of robbery if he uses force against one person to cause the other person to surrender the property.

Purse Snatching is Not Robbery

Some thefts may involve incidental or minimal force. It is not uncommon that a thief will use “force” to effectuate a theft. For example, a pickpocket may intentionally bump into a victim in an effort to distract the victim from a surreptitious theft. When the force used is truly incidental, there is no robbery. To constitute a robbery, the struggle must be something beyond a “sudden” theft. Purse-snatching may not be robbery depending on the force (or lack thereof) used.

The line between robbery and [theft] from the person … is not always easy to draw. The “snatching” cases, for instance, have given rise to some disputes. The great weight of authority, however, supports the view that there is not sufficient force to constitute robbery [if] … the thief snatches property from the owner’s grasp so suddenly that the owner cannot offer any resistance to the taking. On the other hand, when the owner, aware of an impending snatching, resists it, or when[ ] the thief’s first attempt … to separate the owner from his property [is ineffective and] a struggle … is necessary before the thief can get possession [of the property], there is enough force to make the taking robbery.

See Butts v. State, 53 P.3d 609, 612-13 (Alaska App. 2002) abrogated on other grounds by Timothy v. State, 90 P.3d 177 (Alaska App. 2004) (citing 2 Wayne R. LaFave & Austin W. Scott, Jr., Substantive Criminal Law, § 8.11(d)(1), p. 445 (1986) (internal citation omitted)). We explore theft, including theft from the person, in more detail in the next chapter.

If a person uses force to retain property after a theft, the defendant is guilty of robbery. See Ward v. State, 120 P.3d 204 (Alaska App. 2005). A defendant who commits a shoplift and then assaults the security guard in an effort to keep the stolen property commits a robbery. In other words, robbery does not require the force to be used prior to, or while taking the property, but includes force used after the theft.

You be the Judge …

In the early morning hours, Kenneth Moto entered Jacob Vesotski’s home near downtown Anchorage. Vesotski awoke to find a man fumbling with the computer on his desk, which was ten to twelve feet from his bed.

Moto walked toward where Vesotski lay in bed and told him to go back to sleep, “otherwise he was going to kill [him].” When Vesotski realized he was being robbed, he decided to encourage Moto to take whatever he wanted and leave the house. Vesotski unplugged the computer and carried it out of the bedroom to the front door.

Vesotski handed Moto the computer and pushed him out the door. Moto told Vesotski that Moto would kill him if he reported the incident to the police. Moto then left the house with Vesotski’s computer. The police apprehended Moto as he was attempting to enter a neighbor’s house. The police recovered Vesotski’s computer.

Did Moto commit first-degree robbery, second-degree robbery, or simply an aggravated theft offense? Check your answer at the end of the chapter.

Right to Recapture/Reclaim of Property (Self-Help)

You will see in Chapter 14, a person may be justified in using nondeadly force to recapture property if the property is taken from the victim and the victim reacts immediately. Thus, a theft victim may chase someone who stole personal property and take the item back. See Kone v. State, 2018 WL 573339 (Alaska App. 2018). However, the use of force to reclaim property must be immediate. Any appreciable delay converts the use of force into the crime of robbery even if the person is recovering their own property. Using force to reclaim property is only permitted in limited circumstances. Once the theft has been completed, the law requires the victim to use legal methods to reclaim property. Neither force, nor the threat of force, are permitted.

Whitescarver v. State, 962 P.2d 192 (Alaska App 1998)

In the following case, Whitescarver v. State, 962 P.2d 192 (Alaska App 1998), the court explains why a claim-of-right defense is not permitted. As you read Whitescarver, ask yourself if the victim of a theft should be required to invoke legal process to reclaim their own property.

962 P.2d 192

Court of Appeals of Alaska.

Jeffrey Scott WHITESCARVER, Appellant,

v.

STATE of Alaska, Appellee.

No. A–6428.

June 19, 1998.

OPINION

MANNHEIMER, Judge.

This case requires us to decide whether a person may defeat a charge of robbery by showing (or, more precisely, by establishing a reasonable possibility) that they assaulted the victim in an attempt to recover property that rightfully belonged to them. We hold that the answer is “no”: a defendant’s claim of ownership does not justify or excuse an attempt to recover property by assault.

On November 29, 1995, at around 1:30 in the morning, 18–year–old Jeffrey Scott Whitescarver and four of his friends paid a visit to the home of his 64–year–old grandmother, Thelma Whitescarver. Thelma Whitescarver had adopted Jeffrey, and in her capacity as Jeffrey’s adoptive mother, she had applied for and received his Alaska Permanent Fund dividend check. Jeffrey Whitescarver came to his grandmother’s house in the middle of the night because he wished to take personal possession of this dividend money.

Whitescarver’s teenage cousin, Brian Leigh, answered the door. Whitescarver falsely told Leigh that he had locked himself out of his apartment; he asked if he could come in and warm up. Whitescarver entered the house, followed by his companions. One of these companions was holding a shotgun. After they were inside the house, Whitescarver’s companion cocked the shotgun, and then Whitescarver announced that he wanted his Permanent Fund dividend money. Leigh told Whitescarver that he did not have Whitescarver’s money.

Whitescarver and his friends then accompanied Leigh downstairs, so that Leigh could awaken Whitescarver’s grandmother. When Thelma Whitescarver had been roused, Whitescarver repeated his demand for his Permanent Fund dividend money. During the ensuing argument, Whitescarver’s grandmother told him that she did not have access to his money in the middle of the night; she urged Whitescarver to return the next day, during business hours. Whitescarver would not be put off; he told his grandmother that he had waited long enough for his money, and he wanted the money then and there. During this entire argument, one of Whitescarver’s friends stood watch at the door to the room, holding the shotgun.

Whitescarver broke off arguing with his grandmother and conferred with his friends in the hallway. Following this conference, Whitescarver decided he would look for his money in an unlocked safe in the closet. However, he found only papers in the safe.

Whitescarver and his companions conferred again about whether they should “rip off what they could get” from his grandmother’s house. Whitescarver and his friends also discussed what should be done with Whitescarver’s grandmother and cousin. Eventually, Whitescarver and his friends decided to leave his grandmother’s house. As they backed out of the room, Whitescarver’s friend kept the shotgun pointed at Thelma Whitescarver and Brian Leigh. On their way out of the house, Whitescarver or one of his friends stole Thelma Whitescarver’s purse. The purse was later recovered with nothing missing from it.

Whitescarver was indicted on two counts of first-degree robbery (robbery committed while armed with a deadly weapon), AS 11.41.500(a)(1). One count named Thelma Whitescarver as the victim; the other count named Brian Leigh. At his trial, Whitescarver was convicted as charged on the count involving his grandmother. With regard to the count involving his cousin, the jury convicted Whitescarver of the lesser included offense of third-degree assault, AS 11.41.220(a)(1)(A).

Whitescarver’s primary contention on appeal is that the trial judge should have instructed the jury to acquit Whitescarver if they found a reasonable possibility that his act of robbing his grandmother and assaulting his cousin was done for the purpose of recovering property that he honestly believed belonged to him (the money from his Alaska Permanent Fund dividend).

In support of this argument, Whitescarver’s opening brief cites various common-law authorities and a few Alaska cases that discuss issues of peripheral relevance. It is obvious that Whitescarver’s appellate attorney studiously avoided discussing (or even citing) the Alaska case most directly on point, Woodward v. State, 855 P.2d 423 (Alaska App.1993).

[…]

For purposes of analyzing Whitescarver’s case, robbery is essentially an aggravated form of the type of extortion discussed in Woodward —extortion committed by a threat to inflict physical injury. Both offenses involve an attempt, by threat of injury, to induce another person to part with property. If the defendant’s intent is to take property from the victim’s immediate presence and control, and if the threat is of imminent injury, then the defendant’s conduct will constitute robbery. If these two aggravating factors are not present (for instance, if the threat is to inflict injury at some future time), then the defendant’s conduct will constitute extortion.

Viewed in this light, it is evident that there is no “claim of right” defense to robbery—for if, as we recognized in Woodward, the legislature affirmatively manifested its intention to prohibit this defense in cases of extortion by threat of future injury, it is inconceivable that the legislature intended to allow the defense in the more aggravated circumstances of robbery.

Whitescarver attempts to avoid this result by arguing that he had a good-faith belief that his Permanent Fund dividend check was not “property of another”—that he should not be deemed guilty of robbery because he honestly believed that he alone was entitled to the check. However, the crime of robbery does not require proof that the property taken from the victim was “property of another”. As we noted in Woodward, the statutory definition of robbery, AS 11.41.510(a), “[does] not require the taking of ‘property of another’, but only the taking of ‘property’.”

The legislature’s decision to define robbery in terms of “property” rather than the more restrictive “property of another” appears to stem from an explicit policy decision made by the drafters of the Criminal Code. They rejected the common-law view that robbery was “an aggravated form of theft”, and they instead decided to place primary emphasis on “the physical danger to the victim and his difficulty protecting himself from sudden attacks against his person”. The drafters of the Code specifically stated that their definition of robbery was intended to “emphasize[ ] the person, rather than the property, aspects of the offense”.

In other words, even if Whitescarver honestly believed that his grandmother was unlawfully withholding his dividend check from him, Alaska law would not allow Whitescarver to enter his grandmother’s home with a firearm, threaten her with injury unless she surrendered the dividend check, then hold her at bay with the weapon while he examined the contents of her safe and carried off her purse for later inspection. These acts constituted robbery, regardless of who was entitled to possession of the dividend check. Judge Andrews properly refused to instruct the jury on Whitescarver’s proposed “claim of right” defense.

[…]

The judgement of the superior court is AFFIRMED.

Extortion

All states and the federal government criminalize extortion, sometimes called blackmail. A defendant commits the crime of extortion if they obtain the property of another by threatening future physical or reputational harm unless the victim surrenders property. AS 11.41.520. If the defendant threatens immediate physical harm to obtain property (as opposed to future harm), the defendant is guilty of robbery, not extortion.

Reputational harm includes a broad range of threats to a person’s reputation. Specifically, extortion criminalizes threats (1) accusing a person of a criminal offense; (2) exposing confidential information tending to subject any person to hatred, contempt, or ridicule; (3) impairing a person’s credit or business repute; (4) withholding action as a public official; (5) bringing about a strike or boycott; or (6) refusing to testify. To constitute extortion, the motive for the defendant’s threat must be to make someone relinquish property. Note that some of these acts could be legal if not connected with the intent to obtain someone else’s property. But if the victim performs the acts because of the defendant’s threat with the intent to obtain property, then the defendant has committed the crime of extortion.

Coercion

The crime of coercion is essentially a lesser degree of extortion. Coercion prohibits the threat of force against a person to do or abstain from doing an act the victim has a legal right to do or not do. AS 11.41.530. Coercion differs from extortion and robbery, however, in that the defendant’s motive in making the threat is not theft, but rather a more general purpose to compel the victim to engage or abstain in a legal right.

Thus, the crime of coercion applies to a much greater range of motives than either robbery or extortion. For example, a person commits the crime of coercion when the person uses threats to coerce someone into signing a child custody agreement, dropping a lawsuit, or voting for or against a particular candidate or ballot proposition.

Extortion and coercion, like robbery, are crimes of violence. Notice how all three crimes focus on the use, or threat, of force to accomplish the defendant’s goal.