Sexual Violence and Sex Offenses

Alaska has a long, significant, and well-documented problem with sexual violence. Alaska frequently has one of the worst rates of sexual assault in the nation. Some simple statistics put the problem in context. According to the 2020 Alaska Victimization Survey, more than one-third of women in Alaska have experienced sexual assault in their lifetime (40.5%), compared to less than one-fifth of women nationwide. Alaska Native women are disproportionately affected by sexual violence. In 2019, among felony-level sex offense cases reported to Alaska law enforcement, Alaska Native women comprised 50.4% of all victims. See Lisa Purinton, 2019 Felony Level Sex Offenses: Crime in Alaska Supplemental Report (2019). Given the epidemic nature of sexual violence in Alaska, the Alaska legislature is frequently changing the laws surrounding sex offenses. This chapter is not intended to be a comprehensive explanation of Alaska’s sex offenses. Instead, this chapter explores the origins of the crime of rape, subsequent reforms, and the current law. To be clear, the debate surrounding how to appropriately criminalize certain sexual acts – both wanted and unwanted – is far from over. It continues today.

Although Alaska has eliminated antiquated references to the crimes of rape, sodomy, and statutory rape, to fully understand the complexity of the various issues surrounding sex offenses, one must first explore the origins of rape, including what acts were and what acts were not criminalized.

Common Law Rape

For centuries, rape was punishable by death. Rape was “the unlawful carnal knowledge of a woman by a man forcibly and against her will.” See Rape, Black’s Law Dictionary (6th ed. 1990). At common law, carnal knowledge was the penetration of the female sex organ by the male organ. Thus, rape was limited to sexual penetration. The law did not treat sexual contact – nonconsensual touching – as rape. See Wayne R. LaFave, Substantive Criminal Law, §17.2 (3rd ed. 2018). Further, a husband could not be convicted of rape by forcing his wife to engage in sexual intercourse. Spousal rape was not a sexual offense. See id. at §17.4(d).

These were not the only limitations with common law rape. Only a man could commit rape. Women were incapable of committing the crime. Likewise, a man could not be the victim of rape. Same-sex sexual assault was not rape. The crime of sodomy was the penetration of the male anus by another man. But sodomy was condemned and criminalized irrespective of consent because of religious and moral beliefs deeming it a “crime against nature.” See e.g., Harris v. State, 457 P.2d 638 (Alaska 1969).

Modern Trends – Sexual Assault

During the 1970s, many states began to update their antiquated rape statutes. Alaska followed suit. Before the enactment of Alaska’s Revised Criminal Code, Alaska largely tracked the common law definition. The Revised Criminal Code eliminated several outdated terms, concepts, and limitations. The majority of Alaska sex offenses are now categorized as either sexual assault or sexual abuse of a minor. Sexual assault typically refers to criminal conduct against an adult; sexual abuse of a minor typically refers to criminal conduct against a minor. Although modern sex offenses depart from the common law in important ways, you will see the law’s historical roots throughout.

The modern criminal code recognizes that sexual violence need not be sexually motivated. All sex offenses are classified as crimes that violate an individual’s personal autonomy. The sexual act – be it genital penetration, fellatio, or cunnilingus – does not require sexual stimulation, sexual satisfaction, or ejaculation. See Beltz v. State, 980P.2d 474 (Alaska App. 1997). All sex offenses focus on the unwanted sexual activity, not the defendant’s motive for engaging in the activity. Remember that motive is never an element of a criminal offense even though it is frequently helpful in explaining the defendant’s criminal conduct.

The basic purpose of both Sexual Assault and Sexual Abuse of a Minor statutes is to protect victims from offensive and coerced intimacy. Whether charged as sexual assault or sexual abuse of a minor, each offensive act is a violation of the victim’s dignity, personal freedom, and bodily integrity. See Johnson v. State, 328 P.3d 77, 89 (Alaska 2014). Each offensive act constitutes a separate offense.

Alaska’s two general classifications – sexual assault and sexual abuse of a minor – are separately graded based on severity. The code includes four degrees of sexual assault and four degrees of sexual abuse of a minor.

Sexual Assault

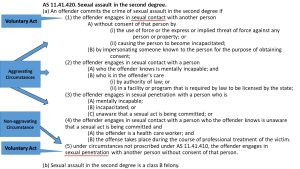

The keys to understanding the different degrees of sexual assault are to understand the necessary mens rea of the offense, the different actus rei involved (“without consent,” “sexual penetration,” and “sexual contact”), and the different aggravating circumstances (“incapacitation,” “force,” and “mentally incapable”). As a general rule, assaults involving sexual penetration are graded higher than assaults involving sexual contact. Aggravating circumstances tend to elevate the offense. For example, sexual assault in the second degree criminalizes aggravated sexual contact, but also “simple” sexual penetration without consent. See Fig 6.4.

Figure 6.4 Alaska Criminal Code – Sexual Assault in the Second Degree (AS 11.41.420)

Mens Rea of Sexual Assault

At common law, rape was a specific intent crime. The government was required to prove that the defendant intentionally engaged in sexual intercourse without the victim’s consent. Under current law, the defendant need not act intentionally but instead must knowingly engage in the sexual act with reckless disregard for the victim’s lack of consent. AS 11.81.610(b). The test for recklessness is a subjective one – the defendant must actually be aware of, and consciously disregard, the victim’s consent. In the eyes of the Alaska Court of Appeals, this rule protects a “defendant against conviction for first-degree sexual assault where the circumstances regarding consent are ambiguous at the time he has intercourse with the complaining witness.” See Reynolds v. State, 664 P.2d 621, 625 (1983). Put another way, the question is whether the defendant understood the victim’s expression of consent (either by words or action), and if consent was not given, whether the defendant was reckless as to the lack of consent.

“Without Consent”

Recall that at common law, rape required the sexual act to be “forcibly and against [the woman’s] will.” The victim had to manifest an extreme resistance to the assault to demonstrate a lack of consent. Early legal scholars viewed a sexual encounter without active resistance as consensual. Rape required proof that the sexual act was achieved by the use of force or threat of force and that it was non-consensual.

Alaska’s criminal code has decoupled force and consent. The law no longer requires the sexual act to be achieved “forcibly and against her will.” Instead, the government must prove that the defendant engaged in the sexual act without the consent of the victim. Resistance is not required; the victim need not fight back or say “no.” Sexual activity may be non-consensual even if the victim acquiesces, freezes, or privately submits. AS 11.41.445(c). Any expression of a lack of consent is sufficient.

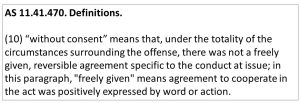

Consent is a positive agreement to cooperate in a specific sexual act. It must be freely given and demonstrated through expressed words or action. Consent is also temporal. It is specific to the sexual act at issue and reversible. Although the defendant must still act recklessly concerning the lack of consent, consent is based on the surrounding circumstances, including what was said (and not said) before, during, and after the encounter. AS 11.41.470(10).

Figure 6.5 Alaska Criminal Code – Alaska Statute 11.41.470(10)

Thus, although a defendant must act recklessly with respect to the victim’s lack of consent, in the simplest of terms, unwanted sexual activity is sexual assault. Sexual penetration without consent is a Class B felony sex offense. Sexual contact without consent is a Class C felony sex offense. Compare AS 11.41.420(a)(5) and AS 11.41.425(a)(7).

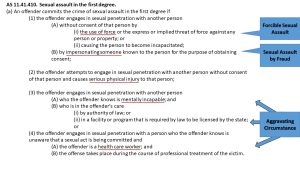

Aggravated Sexual Assault

If a defendant compels sexual activity through force, fraud, or another aggravating circumstance, the crime is elevated to aggravated sexual assault. See e.g., Figure 10.8. For example, first-degree sexual assault (aggravated sexual penetration) outlines six separate aggravating circumstances that, if proven, elevate the assault to either an unclassified or class A felony sex offense. AS 11.41.410(b). Non-consensual sex achieved without the use or threatened use of force, fraud, or other aggravating circumstance remains a sex offense, albeit a lower one. See e.g. Figure 6.6.

Figure 6.6 Alaska Criminal Code – First-Degree Sexual Assault (AS 11.41.410(a))

Forcible Sexual Assault

A defendant’s use of force to commit the sexual act frequently demonstrates that the sexual activity was non-consensual. But this is not always the case. Force does not necessarily prove a lack of consent. For example, “rough sex,” provided it is consensual and does not cause serious physical injury, is not a crime.

For aggravated sexual assault, the defendant’s use of force must go beyond what is necessary to achieve the charged act (i.e., sexual penetration or sexual contact). But recall, Alaska’s definition of “force” is quite broad. Any struggle, resistance, or implicit threat will suffice. See e.g. Dorsey v. State, 480 P.3d 1211 (Alaska App. 2021); Inga v. State, 440 P.3d 345 (Alaska App. 2019). Coercion is evaluated from the perspective of the victim who is subjected to unwanted sexual activity. See State v. Mayfield, 442 P.3d 794, 799 (Alaska App. 2019). To be guilty of forcible sexual assault, the evidence must demonstrate that the victim engaged in sexual activity as the result of coercion (i.e., force or the threat of force) and not as the result of a non-forcible threat (e.g., threatening a victim with economic harm like job termination). Such conduct is still sexual assault, but not aggravated sexual assault. For example, a situation where a person grabs the victim’s genitals spontaneously, and the victim freezes out of shock, but no threats are made, would constitute “simple” sexual assault, not “aggravated” sexual assault.

You be the Judge …

Tim and Mary (Tim’s fiancée) were at a crowded bar in downtown Juneau. The bar was packed and Mary had to guide Tim through the crowd holding his hand. It was impossible to walk through the bar without brushing up against people.

Townsend approached Tim and grabbed and squeezed Tim’s genitals through his clothing for about three to four seconds. Tim dropped Mary’s hand and turned to see who grabbed him. Townsend made eye contact and said, “How are you doing?” Tim and Townsend had never met before. Tim lunged at Townsend but was prevented from reaching him by other people in the bar.

Tim chased Townsend out of the bar and then saw a police officer. Tim reported the incident to the officer. The officer contacted Townsend; Townsend admitted that he grabbed Tim’s genitals and explained that he did this to “hit on” Tim.

The prosecutor charged Townsend with then-second-degree sexual assault, which was defined as engaging in “sexual contact with another person without the consent of that person.” (Formerly AS 11.41.410(a)(1), now AS 11.41.425(a)(7)). Did Townsend touch Tim’s genitals “without consent” as that term is defined in Alaska Law? Check your answer at the end of the chapter.

Sexual Assault by Fraud

A defendant who tricks a victim into having sex by impersonating someone else is guilty of sexual assault. This is a substantial change from common law. Historically, sex by fraud was non-criminal. For example, at common law, a twin who tricked his twin brother’s wife into having sex was not guilty of common law rape. See e.g., People v. Hough, 607 N.Y.S2d 884 (N.Y. 1994). This conduct is criminal under Alaska law. AS 11.41.410(a)(1)(B). Thus, if a victim falls asleep in bed with their lover and, unbeknownst to the victim, another person gets into bed with them, and the victim has “consensual” sex with the person believing the person to be their lover, the person would be guilty of aggravated sexual assault. The government would still need to prove the person took steps to impersonate someone known to the victim, but sex through impersonation is criminal.

Attendant Circumstances – Inability to Consent

There are circumstances when a person is unable to consent as a matter of law. Notably, individuals who are “mentally incapable,” “incapacitated,” or under the “age of consent.” In the eyes of the law, these individuals are unable to make informed decisions, and thus, are unable to consent to otherwise voluntary sexual activity.

Mentally incapable means that the person is suffering from a mental disease or defect that renders the person incapable of understanding the nature or consequence of the sexual act, including the potential for harm the victim may suffer. See AS 11.41.470(4). Recall that a mental disease or defect means the person is incapable of coping with the ordinary demands of life. AS 12.47.130(5).

This group – those who are either temporarily or permanently mentally incapable – comprise a very small segment of the larger mentally impaired population. Mental incapacity means more than mental illness. The victim must not have the capacity to understand the full range of ordinary and foreseeable social, medical, and practical consequences of sexual activity. Profound intellectual disability (formerly called profound mental retardation) falls within this category of mental incapacity. See e.g., Jackson v. State, 890 P.2d 587 (Alaska App. 1995).

Incapacitation, on the other hand, means the victim was temporarily incapable of understanding that they were engaged in sexual activity. Normally, this occurs as the result of extreme intoxication, but may also occur because the victim is unconscious or asleep. If the victim is incapable of understanding that they were engaged in the sexual act – either because of voluntary intoxication or unconsciousness (sleep) – the law treats the victim as incapacitated. See Ragsdale v. State, 23 P.3d 653, 658 (Alaska App. 2001). The unaware victim cannot consent to the sexual act.

Sexual Abuse of a Minor (Statutory Rape) – Modern Trends

Certain minors, depending on their age, cannot consent to sexual activity. They are incapable of consent as a matter of law. Whereas sexual assault requires affirmative proof of the victim’s lack of consent, sexual abuse of minor substitutes the child’s age for proof of consent. These statutes punish all acts of sexual activity between adults and minor children, regardless of whether the child consented to the sexual activity or not. Sexual abuse laws protect children from undue, coercive adult influences, and are intended to deter abusers from preying on children.

At common law, statutory rape prohibited an adult man from engaging in sexual relations with a child under “the age of consent.” See Statutory Rape, Black’s Law Dictionary (6th ed. 1990). Each state determined the age of consent, typically somewhere between twelve and sixteen years old, as it saw fit. See Wayne R. LaFave, Substantive Criminal Law, §17.4(c) (3d ed. 2018).

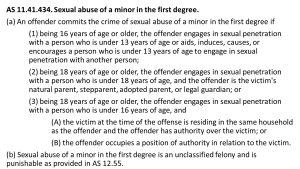

Modern criminal codes, including Alaska’s, have largely maintained the overarching policy of statutory rape: children are too socially and emotionally immature to consent to sex with an adult. Generally speaking, a child under the age of 16 years old cannot consent to sexual activity with an older adult. Although sixteen is commonly referred to as “the age of consent,” the law is more complicated than the phrase suggests. The criminal code has created a web of laws that prohibit older individuals from engaging in either sexual penetration or sexual contact with younger individuals. The prohibited conduct is dependent on both the age of the victim and the age of the perpetrator. Typically, the law creates a three-year age difference requirement to distinguish young adults and older adults. As an example, look at how Alaska’s sexual abuse of a minor in the first degree statute outlines the different prohibited conduct and the required ages of both the offender and the victim.

Figure 6.7 Alaska Criminal Code – Sexual Abuse of a Minor in the First Degree (AS 11.41.434)

Mistake of Age Defense

Historically, the defendant was held strictly liable for the age of the victim. The defendant’s mistaken belief of the victim’s age was no defense. In this sense, statutory rape was considered a strict liability offense. It did not matter whether the defendant honestly and reasonably mistook the victim’s age or even if the victim represented they were older. If the defendant engaged in sexual activity with a child under the age of consent, the defendant was guilty of statutory rape regardless of the circumstances. See e.g., State v. Guest, 583 P.2d 836 (Alaska 1978).

The harshness of this rule has given way to the affirmative defense of the mistake of age. See AS 11.41.445(b). Now, a defendant charged with sexual abuse can present evidence that they honestly mistook the victim’s age (believing the victim was older), and took reasonable measures to verify the victim’s age. As with all affirmative defenses, the defendant bears the burden of proving the existence of the defense. As recognized by the Court of Appeals, “it is fair to expect people to exercise caution when choosing a youthful sexual partner. And, if the defendant claims that a mistake was made, it is fair to expect the defendant to prove the reasonableness of that mistake—to prove that the mistake was not the result of intoxication, lack of concern, or other unreasonable behavior.” Steve v. State, 875 P.2d 110, 123 (Alaska App. 1994), abrogated on other grounds by Jeter v. State, 393 P.3d 438 (Alaska App. 2017).

Position of Authority

In 1990, Satch Carlson, an Anchorage high school teacher, had consensual sex with a seventeen-year-old student. Once authorities discovered the sexual relationship, the government criminally charged Carlson with several counts of sexual abuse of a minor. The statutes in effect at that time prohibited adults from having sex with sixteen- and seventeen-year-old minors entrusted to their care “by authority of law.” The charges against Carlson were dismissed after an Anchorage Superior Court Judge determined that the statutes prohibited sex with legal guardians, but not teachers.

In response to the Carlson decision, the Alaska legislature amended the law to prohibit sexual activity between minors and adults in “positions of authority.” The legislature intended this provision to encompass not just teachers, but “substantially similar” adults “who are in positions that enable them to exercise undue influence over children.” The term position of authority means “employer, youth leader, scout leader, coach, teacher, counselor, school administrator, religious leader, doctor, nurse, psychologist, guardian ad litem, babysitter, or a substantially similar position, and a police officer or probation officer other than when the officer is exercising custodial control over a minor.” AS 11.41.470(5). This list is not exclusive. Any authority figure that is substantially similar to the positions listed will constitute a person in a position of authority. See id.

Sexual Penetration

Recall that at common law, rape required “carnal knowledge.” Modern criminal codes have eliminated such arcane language and replaced it with sexual penetration (or sexual contact where appropriate). The term sexual penetration is very broad, and includes not only genital intercourse, but also cunnilingus, fellatio, and anal intercourse. AS 11.81.900(b)(62). Sexual penetration includes, “any intrusion, however slight, of an object or any part of a person’s body into the genital or anal opening of another person’s body.”

The definition of sexual penetration is intentionally broad, and not limited to medical interpretation. Thus, any intrusion of the victim’s genitals or anus will qualify. For example, the term “vagina” is not a medical term for purposes of sex offenses. Instead, it is used in the broader, colloquial sense. Likewise, “genital” opening is not limited to “vaginal” opening. Female genitalia includes the labia majora, labia minora, and clitoris. In short, the entire female external genital organ. Mason v. State, 2004 WL 1418694 (Alaska App. 1994). This distinction is important as most victims, advocates, and criminal justice practitioners use imprecise medical terminology when describing sexual assaults and sexual abuse.

Sexual Contact

Remember that unwanted sexual contact is typically graded lower than sexual penetration. The term sexual contact means the touching by the defendant of the victim’s genitals, anus, or female breast or the defendant causing the victim to touch the defendant’s or victim’s genitals, anus, or female breast. AS 11.81.900(b)(61). Sexual contact can occur over or under clothing. The victim need not be undressed for sexual contact to occur. Sexual contact may also occur through the unwanted “contact with semen”. See Fig 6.8.

Figure 6.8 – Alaska Criminal Code – Sexual Contact (AS 11.81.900(b)(61))

![AS 11.81.900(b). Definitions. (61) “sexual contact” means (A) the defendant's (i) knowingly touching, directly or through clothing, the victim's genitals, anus, or female breast; (ii) knowingly causing the victim to touch, directly or through clothing, the defendant's or victim's genitals, anus, or female breast; or (iii) knowingly causing the victim to come into contact with semen; (B) [omitted for readability]](https://pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/2614/2022/09/Sexul-contact-diagram-300x169.jpg)

The term “female breast,” as contained in the statutory definition of sexual contact, refers to the breasts of all females, including prepubescent girls without developed breasts; therefore, a defendant can be convicted of second-degree sexual abuse of a minor by touching a nine-year-old girl’s breasts. Stephan v. State, 810 P.2d 564 (Alaska App. 1991). Touching another person’s buttocks does not constitute “sexual contact” under Alaska law, but may constitute the crime of harassment. See AS 11.41.120; State v. Mayfield, 442 P.3d 794 (Alaska App. 2019).

Rape Shield Law

A defendant is not permitted to rely on a victim’s promiscuity to prove consent. The idea that since a victim freely consented to have sex with other people, the victim likely consented to sex with the defendant is a long-outdated view of human sexuality. Such evidence is not admissible. Generally speaking, a victim’s past sexual conduct has no relevance to a victim’s current sexual conduct. Napoka v. State, 996 P.2d 106 (Alaska App. 2000). This rule is codified as Alaska’s rape shield law. See AS 12.45.045.

The statute is designed to protect the victim from unwarranted invasion into their private life. This includes evidence of the victim’s past sexual employment (e.g., adult film star) or sexual orientation. Children are protected from the introduction of their past sexual conduct to the same extent as adults. The rule applies in both sexual assault prosecutions and sexual abuse of a minor prosecutions. If the evidence is built on the inference that the victim freely consented to sex with the defendant because of the victim’s sexual past, then the evidence is irrelevant and inadmissible. See Jager v. State, 748 P.2d 1172 (Alaska App. 1988). Simply put, a person’s prior sexual experience (or lack thereof) is largely irrelevant to whether a person consented to a particular sexual act.

To be clear, the rape shield law only prohibits evidence of a victim’s sexual conduct when the purpose of the evidence is to imply the victim willingly engaged in sexual relations with the defendant because the victim willingly engaged in sexual relations with other people. It is not an absolute bar to the introduction of the victim’s past sexual conduct. If, for example, the victim’s past sexual conduct is offered to explain the victim’s sexualized behavior, it might be admissible (e.g., to explain why a child knows certain “sexualized” terms) or if offered to show the victim had made a prior false allegation of sexual assault. See e.g., Worthy v. State, 999 P.2d 771 (Alaska App. 2000). Likewise, given that consent is based on the “totality of the circumstances surrounding the offense”, it is possible that a court would find that a victim’s past sexual behavior is relevant in determining whether a particular sexual act was consensual under the circumstances. See AS 11.41.470(10).

Example of Relevant Past Sexual Conduct of Victim

Amanda and Sam dated for approximately 6 months, during which time, they engaged in consensual sexual intercourse on several occasions. After they break up, Amanda and Sam engage in sexual intercourse. Amanda reports to police that Sam came to Amanda’s house and forced her to have sex against her will. Amanda tells the police that she tried to stop Sam from coming into her house, but Sam forced his way in and then forced himself on Amanda. When police interview Sam, Sam admits to having sex with Amanda but contends that the sex was “100% consensual”, both before and after their breakup. Sam tells police that he never had non-consensual sex with Amanda. At trial, Sam argues that the entire past sexual relationship between him and Amanda was consensual. Sam wants to tell the jury that Amanda is lying and she is simply mad at him for breaking up with her.

In this case, evidence of Amanda’s past sexual conduct with Sam would be admissible. Amanda’s past sexual conduct with Sam is not excludable under the rape shield law. Sam is not arguing that Amanda is promiscuous, but instead, he is offering evidence to show that they (Sam and Amanda) had a past, consensual sexual relationship. Sam is properly seeking to use this evidence to show that he reasonably believed that she consented to the sexual encounter at issue given their past relationship. The jury is entitled to know about Sam and Amanda’s history of consensual sex in determining whether the sexual encounter at issue was non-consensual. This is not to say that the jury is required to believe Sam. Instead, it is simply a recognition that Sam and Amanda’s past relationship puts the allegation in context.

Sex Offense Penalties

The penalties for sex offenses are significant. For example, first-degree sexual assault carries a presumptive range of 20 to 30 years for a first felony offender, 30 to 40 years for a second felony offender, and 40 to 60 years for a third felony offender. See Figure 1.6. Except for murder, no other crime has such harsh penalties. Even though the legislature enacted significant sentences for sex offenders, the sentences do not constitute cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment or the Alaska Constitution. See Sikeo v. State, 258 P.3d 906, 908 (Alaska App. 2011). Sex offenders also face severe collateral consequences unseen elsewhere in the criminal justice system.

The reason is two-fold: one, sex offenders, similar to murderers, inflict a nearly unmatched level of harm against victims. Victims of sexual violence suffer long-term trauma, especially when the victims are children. Because of the level of harm caused, punishment tends to focus on incapacitation instead of rehabilitation. Second, many believe sex offenders are more likely to recidivate than other offenders. “[A]s a group, convicted sex offenders are much more likely than other offenders to commit additional sex crimes.” Doe v. Pataki, 120 F.3d 1263, 1266 (2d Cir. 1997).

Recent research suggests that the recidivism rationale for harsh criminal penalties for sex offenders may be misplaced. Although a detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this book, there is a significant body of research to suggest that sex offenders are actually less likely to recidivate than other sorts of criminals. Data on the recidivism rates for sex offenders released from prison show that their recidivism rates are relatively low compared to Alaskans convicted of other offenses. See Brad A. Myrstol et. al., Alaska Sex Offender Recidivism and Case Processing Study: Final Report, Alaska Justice Statistical Analysis Center (2016); see also 2019 Sex Offense Report, Alaska Criminal Justice Commission (2019). To be clear, this is not to suggest that sex offenders should receive less harsh penalties, but simply that the stated rationale that sex offenders are more likely to re-offend may be on shaky ground.

Imprisonment is not the only penalty. A host of direct and collateral consequences flow from a criminal conviction for a sex offense. Certain sex offenders are not eligible for discretionary parole unless the three-judge sentencing panel has expressly made them eligible for parole. AS 12.55.125(i)(1)(F); 33.16.090. Sex offenders also receive a heightened level of treatment, programming, and management by the Department of Corrections, both while in-custody and upon release to community supervision. See 2019 Sex Offense Report, Alaska Criminal Justice Commission (2019). Convicted sex offenders are prohibited from holding certain jobs and professional licenses. A complete list of collateral consequences is beyond the scope of this text.

Alaska Sex Offender Registration Act

Sex offenders must also register with the Alaska Department of Public Safety (DPS) under the Alaska Sex Offender Registration Act (ASORA). DPS maintains a publicly searchable, internet-based, central registry of all offenders. The registry provides the offenders’ full name, photograph, home address, and type of criminal conviction. ASORA requires sex offenders convicted of a single, non-aggravated sex offense to register as a sex offender for 15 years. AS 12.63.020(a)(2). Lifetime registration is required when a person is convicted of (1) a single aggravated sex offense, or (2) two or more sex offenses. AS 12.63.020(a)(1)(A). The “two or more” sex offenses may be part of the same criminal proceeding. See Ward v. State, 288 P.3d 94, 95 (Alaska 2012). Thus, a defendant who commits multiple aggravated sex offenses in one episode will be required to register as a sex offender for life, even if the convictions are the defendant’s first criminal convictions.

Although offenders are required to register for significant periods – 15 years or life – depending on the nature of the underlying conviction, an offender is entitled to petition the Superior Court for removal from the registry if the offender can demonstrate that they are no longer a danger to the community. See Doe v. DPS, 444 P.3d 116 (Alaska 2019). Offenders who fail to register with DPS are guilty of a new criminal offense: Failure to Register as a Sex Offender under AS 11.56.840. The first conviction for failing to register is punishable by up to one year in jail; subsequent convictions are felonies. AS 11.56.835.