Offenses Relating to Judicial Proceedings (Obstruction of Justice)

Obstructing justice is defined as “impeding or obstructing those who seek justice in a court[.]” See Obstructing Justice, Black’s Law Dictionary (6th ed. 1990). The term applies to a host of activities that obstruct the administration of justice, including preventing witnesses from appearing, assaulting process servers, influencing jurors, or interfering with criminal investigations. “Obstruction of Justice” is not a crime in Alaska, but the actions that encompass it surely are.

Obstructing justice is simply a broad classification of proscribed conduct that seeks to subvert the legal system. Those who interfere with the legal process through threats, manipulation, or undue influence erode society’s faith in the legal process and procedural justice is impossible unless the government can protect the integrity of the process. We believe that the ultimate decision-maker (i.e., judge or jury) will make its decision free from influence and witnesses will testify truthfully without external pressure.

Conduct that interferes with these principles is prohibited and offenses that interfere with the administration of justice are largely categorized between conduct that involves violence and bribery and conduct that does not. The former is normally graded higher (and has higher penalties).

Interference with Official Proceedings

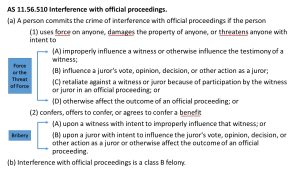

Interference with Official Proceedings is the most serious offense within this category. The statute punishes threats and bribery when such conduct is directed at witnesses, jurors, or the proceeding’s outcome. See Figure 14.1.

Figure 8.1 – Alaska Criminal Code – AS 11.56.510

As you can see, the crime prohibits both the use of force and threaten force against witnesses or jurors. The offense is a specific intent crime. The defendant must act with the intent to “improperly influence” the testimony of a witness. This term – improperly influence a witness – means to cause a witness to testify falsely, offer misleading testimony, or unlawfully withhold testimony. AS 11.56.900(1)(A). It also includes causing a witness to avoid the legal process, absent themselves from a hearing, or engage in evidence tampering. AS 11.56.900(1)(B)-(D). In other words, the statute prohibits any attempt to influence the testimony of a witness if done with force, threats, or bribery. Motive is irrelevant. An individual who beats up a witness to compel the witness to testify truthfully is just as culpable as the person who threatens a witness to ensure they avoid legal process.

Threats need not be explicit. Veiled threats suffice. If the defendant’s words or conduct could reasonably communicate an intention to inflict harm, then the defendant has “threatened” the witness. See e.g., Baker v. State, 22 P.3d 493 (Alaska App. 2001). Thus, it is just as criminal to tell a witness that she had “better shut her mouth, or I’ll shut it for her”, as it is for a person to overtly threaten to kill the witness if she shows up to court. See id. at 497.

Violence or threats of violence directed at jurors, if done with the intent to influence the juror’s vote, opinion, or decision, is equally prohibited. AS 11.56.610(a)(1)(B). Assaultive conduct that interferences with a juror’s ability to make its decision is punished to the same level as threats directed at witnesses.

The statute also prohibits a defendant from using force (or threatening the use of force) to retaliate against a witness or juror because the person participated in an official proceeding. AS 11.56.510(a)(1)(C). Thus, a defendant who threatens a juror after a trial (because the juror voted to convict) is still guilty of official interference, even though the conduct occurred after the verdict.

Finally, the statute criminalizes any threatening conduct designed to affect the outcome of the official proceeding. AS 11.56.510(a)(1)(D). This would include threatening to hurt a juror’s family offering a bribe to a witness with the intent to cause a mistrial or general menacing behavior directed at a judicial officer if done to obtain a particular result.

The statute contains a second general prohibition – the prohibition against bribing witnesses or jurors with the intent to improperly influence the witness’s testimony or juror’s opinion. AS 11.56.10(a)(2). This provision is similar to the code’s general bribery statute but is specifically tailored to protect witnesses and jurors. Bribery is treated as serious as threats of violence.

The statute protects more than criminal jury trials. Official proceeding is defined as a proceeding “heard before a legislative, judicial, administrative, or other government body … authorized to hear evidence under oath.” AS 11.81.900(b)(43). Thus, a person who threatens a witness during a legislative hearing is just as guilty as the person who threatens a witness during a criminal jury trial.

The term witness is broadly defined. Witness means a person summoned or appearing to testify in an official proceeding or a person who the “defendant believes may be called as a witness in an official proceeding, present or future”. AS 11.56.900(6). The code explicitly defines witness from the perspective of the person charged with interfering with the official proceeding (i.e., the defendant). Thus, if the defendant believes a person may be a witness in an official proceeding, it is immaterial that the person is in fact, not a potential witness. Likewise, it is immaterial whether the government knows the person is a witness. So long as the defendant knows the person is a potential witness, the person is a “witness” for criminal liability. This definition avoids confusion as to when an individual actually becomes a witness and instead, focuses on protecting witnesses and the integrity of the system.

The term juror includes all members of impaneled juries, including grand juries, as well as persons who have been drawn or summoned to appear as prospective jurors. Thus, a person threatened on their way to jury duty is entitled to receive the same protection as the impaneled juror. AS 11.56.900.

Constitutional Challenges

Because these offenses limit a person’s speech, the question frequently arises whether such speech is protected under the First Amendment. Recall that doctrine of free speech does not protect all speech. Although a person may use caustic, offensive, and even potentially intimidating language in communication, the First Amendment does not protect “true threats.” As described by the Alaska Court of Appeals, “a person has no First Amendment right to ask other people to lie under oath or to try to persuade them to do so.” See Baker v. State, 22 P.3d 493 (Alaska App. 2001). The difficulty is distinguishing between threats and hyperbole. Hyperbole, particularly political hyperbole, is protected speech, and in the eyes of the U.S. Constitution, necessary to ensure a robust, wide-open debate about governmental policy.

You be the Judge …

William, a resident of Valdez, learned that the local telephone company had terminated his cell phone service without his prior knowledge. The dispute progressed until William filed a civil complaint in Valdez Superior Court against the telephone company. Shortly after the telephone company filed its Answer, William went to the courthouse and spoke with a state magistrate. William demanded that his case be set for a jury trial immediately. The magistrate explained to William that setting a trial date was not a simple task and required the involvement of a Superior Court Judge in Anchorage.

William grew angry and began yelling at the magistrate. The magistrate became so frightened that she locked the door to her chambers. William eventually left. Two days later, Williams sent the following letter to the courthouse:

To Whom It May Concern:

I am still waiting for my trial date in the above case. When the telephone company suspended phone service to my business it was for the express purpose of forcing hardships upon my family. I’ve had enough. I told them when I lost my home if I had not received a fair trial by jury I was going to kill the things. Last week I signed a quitclaim to my home and property. I can stay until I get an honest trial or someone else buys the property. As far as I am concerned the things are living on borrowed time. And this is the last time I am asking for my rights as a human.

After learning of the letter, law enforcement interviewed William. William confirmed that the letter’s apparent threat to kill “the things” was directed at the magistrate. William also told officers he wrote the letter in the hopes that he would be arrested so he could receive a trial date sooner. The government indicted William on one count of interference with official proceedings in violation of AS 11.56.510(a)(1)(D) for sending the threatening letter.

Based on these facts, would William be successful in arguing that the statute impermissibly infringed upon his First Amendment rights? Check your answer at the end of the chapter.

Receiving a Bribe by a Witness or Juror

Just as the law prohibits a person from bribing a witness or juror, the law equally prohibits a witness or juror from receiving a bribe. The crime of Receiving a Bribe by a Witness or Juror is committed when a witness or juror solicits, accepts, or agrees to accept, a benefit with the understanding that they will be improperly influenced as a witness or as a juror. AS 11.56.520. Receiving a Bribe is a class B felony offense, similar to Interference with a Official Proceeding and is punishable by up to 10 years imprisonment. Again, this statute is modeled after the code’s general bribery statute.

Witness Tampering

Witness tampering criminalizes conduct that unduly influences a witness’s participation or testimony in a judicial hearing. Alaska has separated witness tampering into two degrees: first- and second-degree witness tampering. The former is a class C felony, whereas the latter is a class A misdemeanor.

A person commits the crime of first-degree witness tampering if the person knowingly induces a witness to testify falsely, offers misleading testimony, unlawfully withholds testimony, or causes the witness to be “absent from a judicial proceeding to which the witness has been summoned”. AS 11.56.540.

This is much different than the crime of interference with an official proceeding discussed above. Witness tampering does not involve the use of force, threats, damage to property, or bribery. Merely inducing a witness is not as blameworthy as threatening violence or offering a bribe.

Persuading a witness to avoid legal process (for example, to avoid being served with a subpoena) is not a crime, unless the defendant uses forces or the threat of force. This line – the line between witness tampering and lawfully explaining the legal process – is a fine one. It is not unlawful to instruct a witness that they need not appear in court or testify unless subpoenaed. It is not unlawful to tell a witness to refuse to cooperate with law enforcement. It is not unlawful to tell a witness not to elaborate with asked questions. See e.g., Rantala v. State, 216 P.3d 550, 555 (Alaska App. 2009). It is unlawful to disobey a court order. Once a subpoena has been served, any persuasion, done with the intent to cause the witness to disobey the subpoena, constitutes witness tampering.

Further, context matters. If a defendant tells a witness to be non-cooperative or avoid process, and in context, the defendant is attempting to pressure the witness to testify falsely or withhold testimony, then the defendant is guilty of witness tampering.

You be the Judge …

Boggess began sexually abusing his eleven-year-old stepdaughter during the summer of 1985. During the police investigation, officers learned that Boggess’s wife could corroborate some of her daughter’s statements. Immediately before the grand jury presentation, a witness heard Boggess tell his wife to “plead the fifth” or “break down and cry” instead of answering the prosecutor’s questions.

Upon hearing this evidence, the grand jury indicted Boggess with first-degree witness tampering for attempting to induce his wife to “unlawfully withhold testimony in an official proceeding.”

do you think this conduct is witness tampering or witness preparation? Why or why not? Check your answer at the end of the book.

Second-degree witness tampering occurs if a person knowingly induces a witness to be absent from an official proceeding, other than a judicial proceeding, to which the witness has been summoned. AS 11.56.545. Thus, a defendant who causes a person to be absent from a legislative, administrative, or other adjudicative hearing after being summoned, is guilty of misdemeanor witness tampering. The offense is only elevated to a felony if the hearing is a “judicial proceeding”.

Jury Tampering

The crime of jury tampering is committed when a person directly or indirectly communicates with a juror other than as permitted by court rules. AS 11.56.590. The perpetrator must act with the intent to influence the juror’s vote. The crime of jury tampering differs from interference with an official proceeding only in one respect – a lack of bribery or force. If the attempt to influence a juror’s vote is committed without a bribe and without force (or the threat of force), the tampering is less serious in the eyes of the law – it only constitutes a class C felony. Threatening a juror or bribing a juror, on the other hand, is a much more serious offense.

Misconduct by a Juror

Conversely, misconduct by a juror is committed when a juror promises, before submission of the case to the jury, to vote for a particular verdict. AS 11.56.600. This includes conduct that may only cause a mistrial (i.e., refusing to reach unanimity for purpose of a verdict). Note that this crime supplements the trial court’s general power of contempt of court. Contempt of court is the inherent power to punish a person for the willful disobedience of a court order. A court always has the power to hold a juror in contempt should the juror violate a court rule.

Misconduct by a juror is similar to the crime of receiving a bribe by a juror, but unlike receiving a bribe, this crime does not require the consideration of a benefit. Instead, the crime simply requires the juror to agree to a particular verdict outside of the trial process.

Simulating Legal Process

The crime of simulating legal process is a relatively new and very rarely charged offense. It protects the legitimacy of government administration by maintaining the public’s trust and confidence in genuine governmental documents. The offense prevents a person who is attempting to collect a debt from using a document that has the appearance of being court-issued, such as an attachment, execution, judgment, or lien. AS 11.56.650(2). It also covers the fraudulent use of subpoenas, summons, and similar documents (i.e., warrants) that have the appearance of being court-issued. AS 11.56.650(2).

What is simulating legal process anyhow?

Ed and Paul are in a dispute over the property boundaries on their adjoining land. Ed sued Paul in small claims court. Ed asks the previous owner of the land, Sam, to testify in court. Sam refuses to testify unless ordered to do so by the court. Ed knows it’s too late to get the court to issue a subpoena. Ed makes a copy of another subpoena, changes the name to Sam, and sends it to Sam.

In this example, Ed has committed the crime of simulating legal process by issuing and sending a simulated subpoena with the intent to cause Sam to appear at trial. (Note: Ed has also likely committed second-degree forgery under AS 11.46.505(a)(2) for falsely altering a written instrument that is a public record.)

Tampering with Physical Evidence

The crime of tampering with physical evidence prohibits tampering with “physical evidence” – a term that refers to any “article, object, document, record, or other thing of physical substance.” AS 11.56.900(4). The object need not be admissible evidence or evidence admitted in court. It simply needs to an object that is relevant to the investigation.

The code outlines three separate methods of tampering with physical evidence. AS 11.56.610. As you will see, evidence tampering is a specific intent crime – the offender must have a conscious objective to achieve the intended result. First, the offense prohibits the intentional destruction, mutilation, alteration, concealment, or removal of physical evidence with the intent to “impair its verity” (i.e., truthfulness) or its “availability in a criminal investigation.” AS 11.56.610(a)(1). Second, the crime prohibits the making, presenting, or using evidence known to be false in a proceeding with the intent to mislead a juror or a criminal investigation. AS 11.56.610(a)(2). Third, the offense prohibits the use of force, deception, or threats to prevent the production of physical evidence during a criminal investigation. AS 11.56.610(a)(3). Finally, the statute criminalizes conduct identical to the above three paragraphs, but done with the intent to prevent the initiation of an official proceeding. This final paragraph covers those situations where a person tampers with physical evidence, with the intent to prevent the initiation of a non-criminal official proceeding (i.e., a legislative or civil investigation). AS 11.56.610(a)(4).

As a crime, evidence tampering has broad reach. Every act of evidence tampering is a felony regardless of the underlying offense. Thus, it is irrelevant that the underlying offense to which the evidence relates is a misdemeanor or violation. The destruction or alteration of evidence constitutes a felony offense. See Y.J. v. State, 130 P.3d 954 (Alaska App. 2006).

You be the Judge …

Officers received a detailed report of a shooting near a residence in Fairview. Although no one was injured in the shooting, several individuals provided officers with a detailed description of the shooter and the vehicle involved. Officers located the suspect’s vehicle quickly and attempted to stop it. A chase ensued through the neighborhood. During the chase, the driver, Anderson, tossed several items related to the shooting out of the vehicle, including the handgun, the firearm’s magazine, and a box of matching caliber ammunition.

Do you think Anderson has committed the crime of tampering with physical evidence for throwing the items out of the car window under AS 11.56.610(a)(1) (that is, for concealing the evidence with the intent to impair its availability in a criminal investigation under)? Check your answer at the end of the chapter.

Exercises

Answer the following questions. Check your answers at the end of the chapter.

- Two months after the shooting of Victor, detectives learn that a witness (Bobby) saw the suspect, Homer Frink, shoot Victor. When interviewed, Bobby tells detectives that he did not come forward earlier because Frink threatened to shoot Bobby if he talked to the police. In addition to homicide, what crime has Frink committed? Why or why not?

- In response to a newspaper ad seeking information about witnesses to a collision between two cars, John Citizen reports that Bobby Bystander was standing at the intersection when the car driven by the defendant ran the red light and was struck broadside by the car driven by Plaintiff. The Plaintiff has hired a private investigator, Rick, to contact witnesses. Investigator Rick contacts Bobby who at first refuses to say anything. Bobby tells Investigator Rick he does not want to be involved. Investigator Rick then offers Bobby $500.00 to tell him what he saw. Bobby accepts the money and tells Rick that he saw the defendant run the red light. Has Investigator Rick committed a crime? Why or why not?