Theft and Related Offenses

Although violent crimes like murder, sexual assault, and robbery are considered particularly heinous, crimes against property can cause enormous loss and suffering, and even injuries or death in some extreme situations. This chapter explores different types of common property crimes, including theft, crimes that invade property like burglary and trespass, arson, and finally, criminal mischief (vandalism).

While this chapter explores crimes against property as a category, not all property is created equal. The law distinguishes crimes depending on the type of property interfered with. Generally, the property falls into one of three categories: real property, personal property, and personal services. Real property is land and anything permanently attached to the land, like a building. Personal property is any tangible or intangible item, but which is movable. Tangible property includes items like money, jewelry, vehicles, clothing, and the like. Intangible property means an item that has value, even though it cannot be touched or held, like stocks and bonds. Personal services include any activity provided by a provider of services.

Consolidated Theft Statutes

Common law theft was separated into three categories: larceny, embezzlement, and false pretenses. The categories differed in the type of property stolen and the method of stealing. Modern jurisdictions have largely abolished these common law categories. Instead, modern criminal codes rely on consolidated theft statutes, which provide a uniform grading system dependent largely on the value of the stolen property or the type of property stolen. What follows is a discussion of theft as defined under Alaska’s modern consolidated theft offenses.

Alaska’s Modern Consolidated Theft Offenses

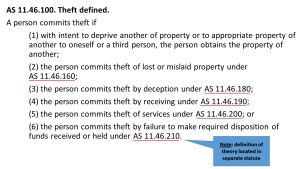

The primary purpose of Alaska’s statutory theft scheme is the consolidation of the common law “theft-like” crimes, including larceny, larceny by trick, embezzlement, theft of mislaid property, false pretenses, receiving stolen property, and theft of services. The Alaska Legislature eliminated all of these distinct crimes. Alaska now defines “theft” in six separate ways, but largely codifies the former law. Figure 11.1 (AS 11.46.100) outlines the conduct constituting theft. Note that the statute only defines what “theft” is; a person accused of theft is not charged under AS 11.46.100. Instead, the accused thief is charged under one of the degrees of theft (explained below).

Figure 7.1 Alaska Criminal Code – Theft defined

These subsections refer to individual statutes describing how a particular form of theft may be committed. Each particular form is a theory of theft. A theory of theft is how the theft was committed – the degree of the theft is determined by the value or item(s) stolen.

Although theft is defined in one of the above-six ways, it is graded into four degrees for purposes of punishment, depending primarily on the value of the property or services that was the subject of the theft. For example, if the property stolen is valued at more than $25,000, the crime is theft in the first degree, a Class B felony. AS 11. 46.120. On the other hand, the crime of second-degree theft, a class C felony, is committed when the property stolen is valued at more than $750 but less than $25,000 or the item stolen is a firearm or explosive, regardless of the value. Compare AS 11.46.130(a)(1) and 11.46.130(a)(2). Thefts under $750 are treated as misdemeanors.

As you will see, theft spans a wide range of different behavior. The Legislature specifically defined theft broadly to eliminate the confusing distinctions between historical theft offenses. Common law was frequently plagued with confusing and narrow distinctions between the various forms of larceny. See e.g. Williams v. State, 648 P.2d 603 (Alaska App. 1982). The legislature’s change makes sense: at the end of the day, a victim has suffered loss at the hands of a thief. The defendant’s criminal liability should not be dependent on what the theft is called. Legally speaking, a defendant charged with theft is on notice that they may be convicted of theft under any of the different theories. What follows is a summary of the six theories of theft.

Obtains Property of Another with the Intent to Deprive

The first theory of theft is when a suspect obtains the property of another with the intent to either: (a) deprive another of the property, or (b) appropriate property of another. This theory encompasses both common law larceny and common law embezzlement.

This theory, like most theories of theft, is a specific intent crime. The suspect must have a conscious objective to deprive the rightful owner of the property. AS 11.46.990(8). Thus, “borrowing” property with the intent to return it later does not constitute theft. Theft requires that the defendant either permanently deprive the owner of the property’s use or deprive the owner of the property for a period of time whereby the property’s economic value is lost.

A person can deprive another of property in several ways, including disposing of the property so that it is highly unlikely that the rightful owner will get it back, not returning it unless the owner pays a reward for its return, or transferring any interest in the property. For example, imagine a thief who uses a stolen generator for several days and then throws it into a lake to hide the evidence of the crime. In this scenario, the thief acts with the “intent to deprive another person of property” since he disposed of the property in a way that it is unlikely that the rightful owner will get it back.

Not only must the thief intend to deprive the owner of the property, but the thief must also obtain the property. Obtain simply means that the defendant exercised control over the property. This would include taking, withholding, or appropriating property of another. There is no requirement that the property be carried away as was required under common law larceny (sometimes called “asportation”). In modern times, this means that the property need not be moved to constitute theft. A defendant can appropriate property if the defendant controls the property so that the economic benefit goes to the defendant and not to the rightful owner, or the defendant disposes of the property for the benefit of himself. AS 11.46.990(2).

Simon v. State, 349 P.3d 191 (Alaska App. 2015)

In the following case, the Court of Appeals discusses how the legal definition of “obtains” (for purposes of theft) is broader than one may initially think. Simon v. State analyzes the actus reus of theft in the context of shoplifting. As you read the opinion, notice how the court points out that a shoplifter need not actually deprive a store of their property to be guilty of theft. If a shoplifter exercises unauthorized control over property with the intent to deprive, the essential elements of theft have been satisfied.

349 P.3d 191

Court of Appeals of Alaska.

Harold Evan SIMON, Appellant,

v.

STATE of Alaska, Appellee.

May 8, 2015.

OPINION

MANNHEIMER, Judge.

The earliest, most classic definition of theft is laying hold of property that you know belongs to someone else and carrying it away without permission, with the intent to permanently deprive the owner of the property. The present case requires us to examine how this general notion of theft applies to modern retail stores—stores where customers are allowed to take merchandise from the shelves or display cases, and walk around the store with these items, until they ultimately pay for the items at a checkout station.

The State contends that if a person intends to take the property without paying for it, then the crime of theft occurs at the moment the person removes an article of merchandise from a shelf or display case within the store. The defendant, for his part, contends that the crime of theft is not complete until the person physically leaves the store.

For the reasons explained in this opinion, we conclude that the true answer lies in between the parties’ positions: In the context of a retail store where customers are allowed to take possession of merchandise while they shop, the crime of theft is complete when a person, acting with the intent to deprive the store of the merchandise, performs an act that exceeds, or is otherwise inconsistent with, the scope of physical possession granted to customers by the store owner.

In the present case, the parties disagreed as to precisely where the defendant was located when he was stopped by the store employee: whether he had reached the outer door of the store, or whether he was still inside the vestibule leading to that outer door, or whether he was merely approaching that vestibule. But it was undisputed that the defendant had already gone through the check-out line, and that he had paid for a couple of inexpensive items while, at the same time, either hiding or disguising other items of merchandise—items that he then carried toward the exit.

Even viewed in the light most favorable to the defense, this conduct was inconsistent with the scope of physical possession granted to customers by the store owner. This conduct therefore constituted the actus reus of theft—the physical component of the crime. This conduct, coupled with the mental component of the crime (intent to deprive the store of the property), made the defendant guilty of theft. We therefore affirm the defendant’s conviction.

Underlying facts

The defendant, Harold Evan Simon, went into a Walmart store in Anchorage. Like many other retail merchants, Walmart allows its customers to exert control over its merchandise before making a purchase: customers are allowed to roam the aisles of the store, to handle and examine the items that are offered for sale, and to take these items with them (either in their hands, or in a basket or shopping cart) as they walk through the store, before going to the cash registers or scanning stations to pay for these items.

While Simon was walking through the Walmart store, he took a jacket from a sales rack, put it on, and continued to wear it as he walked through the store. Simon also took a backpack and started carrying it around. At some point, Simon placed several DVDs in the backpack. Simon also picked up a couple of food items. Finally, Simon went to the row of cash registers. He paid for the food items—but he did not pay for the jacket, the backpack, or the DVDs hidden in the backpack.

Simon then left the cash register area and headed for the store exit. Before Simon reached the exit, a Walmart employee approached him and detained him. Simon handed the backpack to the employee, and then he removed the DVDs from the backpack. Simon told the Walmart employee, “There you go; there’s your stuff. I’m sorry; I was going to sell it.” A short time later, the police arrived, and they noticed that Simon’s jacket was also unpaid-for. (It still had the Walmart tags on it.)

Based on this incident, and because of Simon’s prior convictions for theft, Simon was indicted for second-degree theft under AS 11.46.130(a)(6) (i.e., theft of property worth $50 or more by someone with two or more prior convictions for theft within the previous five years). Simon ultimately stipulated that he had the requisite prior convictions, so the only issue litigated at Simon’s trial was whether he stole property worth $50 or more.

The State presented the evidence we have just described. Simon presented no evidence. In his summation to the jury, Simon’s attorney focused on potential weaknesses in the State’s proof, and he argued that Simon might have been so intoxicated that he lacked the culpable mental state required for theft (the intent either to deprive Walmart of the property or to appropriate the property for himself). Additionally, toward the end of his summation, Simon’s attorney suggested that Simon “didn’t deprive anyone of property” because “he didn’t even enter the vestibule [leading to the final exit door]”.

This latter argument mistakenly conflated the “conduct” component and “culpable mental state” component of the crime of theft. The State was not required to prove that Simon actually deprived Walmart of its property. Rather, the State was required to prove that Simon exerted control over the property with the intent to deprive Walmart of its property (or to appropriate the property to his own use). See AS–11.46.100(1).

But it appears that the defense attorney’s argument struck some of the jurors as potentially important—because, during its deliberations, the jury sent a note to the judge in which they asked about the vestibule. The jury’s note read: “At what point does [the] defendant ‘exert control over the property of another’ [in] reference to the vestibule area … [and] # 20 of [the jury] instructions[?]”

(The jury instructions informed the jurors, in accordance with AS 11.46.100(1) and AS 11.46.990(12), that before Simon could be found guilty of theft, the State had to prove that Simon “exert[ed] control over the property of another”.)

After conferring with the parties, and without objection from Simon’s attorney, the trial judge responded to the jury’s question [by stating,

The issue for you to decide is whether the State proved, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the defendant intended to take the items from Walmart without paying for them, without regard to any particular area where he was confronted by the Walmart employee.]

[…]

Shortly after receiving [this] reply from the judge, the jury found Simon guilty of theft.

Six days later, Simon’s attorney filed a motion for a new trial, arguing that the judge had committed reversible error in his answer to the jury’s question. Even though Simon’s attorney had not objected to the wording of the judge’s answer (indeed, Simon’s attorney had actually contributed to the wording of the judge’s answer), the attorney now contended that there was a flaw, amounting to plain error, in the wording of the first sentence of the second paragraph.

According to the defense attorney, that sentence should have been worded, “One issue for you to decide …”, rather than “The issue for you to decide …”, because more than one issue was contested at Simon’s trial. The defense attorney pointed out that he had contested the State’s evidence regarding Simon’s culpable mental state, and that he had also argued that Simon might only be guilty of attempted theft, rather than the completed crime.

[…]

Our call for supplemental briefs on how to define the actus reus of theft in this context, and the parties’ positions

Although the judge’s answer to the jury was not flawed in the way Simon contended in his opening brief, the judge’s answer was potentially flawed in another way—because, depending on how the phrase “exert control over property of another” is defined in the context of a retail store, Simon’s location at the time he was apprehended might possibly be the factor that distinguished a completed act of theft from an attempted theft.

We therefore asked the parties to submit supplemental briefs on the issue of what, exactly, is the actus reus of theft in the context of a retail store where customers are allowed to take possession of items of merchandise while they shop.

In its supplemental brief, the State argues that if a person intends to take an article of merchandise without paying for it, then the crime of theft is complete at the moment the person first “exerts control” over that merchandise—by which the State means the act of taking the item from its shelf or display case. Simon, on the other hand, argues that even if a person takes an article of merchandise off the shelf with the intent to steal it, the crime of theft is not complete until the person physically leaves the store with the merchandise.

Why we conclude that, in this context, Alaska’s definition of theft requires proof that the defendant did something with the merchandise that was outside the scope of, or otherwise inconsistent with, the possession authorized by the store

The general definition of the crime of theft is contained in AS 11.46.100(1). Under this definition, theft occurs if a person “obtains the property of another”, acting with the intent “to deprive another of property or to appropriate property of another to oneself or a third person”.

For purposes of the issue raised in Simon’s case, the key portion of this definition is the word “obtains”. This word is defined in AS 11.46.990(12); the relevant portion of that definition is: “to exert control over property of another”.

In situations where the accused thief had no right at all to exert control over the other person’s property, this definition expresses our traditional notion of theft. It describes what most of us think of when we hear the word “theft”—situations where a thief picks up someone else’s property and makes off with it.

The State contends that this definition applies equally to the circumstances of Simon’s case. The State argues that a person in a retail store “exerts control” over an item of merchandise when they pick it up and take it from the shelf or display case. Thus, if a person performs this action with an intent to steal the item, the crime of theft is complete—even if the person is apprehended before they ever attempt to leave the store.

It is true that, in common usage, one might say that shoppers “exert control” over the items that they take from the shelves and put in their shopping baskets (or carry in their hands). But the State’s proposed interpretation of the statute is inconsistent with the traditional common-law approach to theft.

Our present-day crime of theft covers conduct that, at common law, was viewed as two different offenses: larceny and embezzlement.

The common-law crime of larceny covered classic instances of theft, and it required proof of a “trespassory taking”. That is, the government was required to prove that the defendant committed a trespass—violated someone else’s property rights—when they exerted physical control over the property.

The English judges were willing to stretch the concept of trespassory taking to cover situations where the defendant acquired possession by fraud—i.e., situations where the owner of the property voluntarily gave possession (but not title) to the defendant because of the defendant’s lies. But the common-law crime of larceny did not apply to situations where, in the absence of fraud, the owner voluntarily allowed another person to take possession of the property.

For example, a wealthy person might entrust a butler or maid with daily custody of their silverware, or they might take the silverware to a shop and temporarily leave it with the employees for polishing or cleaning. Or, turning to more modern situations, people who are about to purchase a house or other real estate will ordinarily leave a large sum of money in escrow with a third party (a bank or an escrow company), with instructions that the money be transferred to the seller if the deal is successful. And the owners of businesses ordinarily entrust their bookkeepers with checkbooks or access codes that allow the bookkeepers to pay bills, pay employees’ salaries, and otherwise disburse the company’s funds for business purposes.

To cover situations where theft occurred after the owner of the property voluntarily allowed one or more people to exert control over the property for a particular purpose (or range of purposes), a new crime was created: “embezzlement”.

In these situations, one might reasonably say that the employees or custodians were already “exerting control” over the owner’s property (with the owner’s permission) before they stole it. Accordingly, one might argue that these employees or custodians became guilty of embezzlement at the very moment they formed the mens rea of the crime—the moment they decided to deprive the owner of the property—even if they performed no further action toward this goal.

But one of the axioms of the common law was that a person should not be punished for their thoughts alone. Thus, in prosecutions for embezzlement, proof of the defendant’s larcenous thoughts was not enough: the common law required proof that the defendant’s conduct departed in some way from the conduct of someone who was dutifully upholding the property owner’s trust (and that this conduct was prompted by an accompanying intent to steal). The government was required to prove that the defendant exerted unauthorized control over the property—i.e., engaged in conduct with the property that was inconsistent with the type or scope of control that the property owner had allowed.

When the drafters of the Model Penal Code created the crime of “theft” (a crime that was intended to encompass and modernize the common-law crimes of embezzlement and larceny in its various forms), the drafters expressly included this concept of exerting unauthorized control.

Model Penal Code § 223.2(1), the provision that defines the crime of theft as it relates to movable property, declares that a person is guilty of theft if the person “unlawfully takes, or exercises unlawful control over, movable property of another with purpose to deprive him thereof.” (Emphasis added) And in Section 2 of the Comment to § 223.2, the drafters emphasized that the crime of theft requires an unauthorized taking or an unauthorized exercise of control:

The words “unlawfully takes” have been chosen to cover [all] assumption of physical possession or control without consent or authority…. The language “exercises unlawful control” applies at the moment the custodian of property begins to use it in a manner beyond his authority…. The word “unlawful” in each instance implies the [actor’s] lack of consent or authority [for the taking or the exertion of control].

American Law Institute, Model Penal Code and Comments, Official Draft and Revised Commentary (1962), pp. 165–66.

In Saathoff v. State, 991 P.2d 1280, 1284 (Alaska App.1999), this Court recognized that this provision of the Model Penal Code “appears to be the source of the definition of ‘obtain’ codified in AS 11.46.990[ (12) ]—‘to exert control over property of another’.”

But unlike the vast majority of other states that enacted theft statutes based on the Model Penal Code, the drafters of Alaska’s criminal code did not include the words “unauthorized” or “unlawful” when they defined the word “obtain”. Instead, the drafters defined “obtain” as simply “to exert control over property of another”. See Tentative Draft 11.46.990(6), Alaska Criminal Code Revision Subcommission, Tentative Draft, Part 3 (“Offenses Against Property”), p. 98.

There is nothing in the Tentative Draft of our criminal code explaining (or even commenting) on the drafters’ omission of “unauthorized” or “unlawful”. There is only a derivation note, saying that Alaska’s definition was based on the Oregon theft statutes—that it came from Oregon Statute 164.005. Id. at 104.

This Oregon statute uses the word “appropriate” rather than the word “obtain” to describe the actus reus of theft. But, like Alaska’s definition of “obtain”, the Oregon definition of “appropriate” does not include the words “unauthorized” or “unlawful”:

“Appropriate property of another to oneself or a third person” or “appropriate” means to:

(a) Exercise control over property of another, or to aid a third person to exercise control over property of another, permanently or for so extended a period or under such circumstances as to acquire the major portion of the economic value or benefit of such property; or

(b) Dispose of the property of another for the benefit of oneself or a third person.

But even though this statutory language does not expressly include the modifiers “unauthorized” or “unlawfully”, the Oregon courts have construed this language to require proof that, when the defendant “appropriated” the property of another, the appropriation was unauthorized or unlawful—in the sense that it constituted a “substantial interference with [another person’s] property rights”, State v. Gray, 543 P.2d 316, 318 (1975), or that it constituted an “unauthorized control of property”, State v. Jim, 508 P.2d 462, 470 (1973).

The Oregon Court of Appeals’ decisions in State v. Gray and State v. Jim were issued before the Alaska Criminal Code Revision Subcommission drafted our theft provision in 1977. Thus, when the drafters of the Alaska theft statutes composed our definition of “obtain” (based on the Oregon statute), the Oregon courts had already construed their statute to require proof of an unauthorized exertion of control (even though the statute did not explicitly mention this requirement).

For these reasons, we hold that Alaska’s definition of “obtain”, AS 11.46.990(12)(A), includes a requirement that the defendant’s exertion of control over the property was unauthorized. This interpretation of the statute is supported by the principles of the common law, it is consistent with the law of Oregon (the state from which our statute was immediately derived), and it brings Alaska’s law of theft into conformity with the law of every other jurisdiction (at least, every other jurisdiction we are aware of) that has enacted theft statutes based on the Model Penal Code.

Application of this law to Simon’s case

We have just held that the actus reus of theft requires proof, not just that the defendant exerted control over someone else’s property, but that this exertion of control was unauthorized. […] Depending on the facts of a particular case, it might make a difference where a shoplifter is apprehended—because there might be cases where defendants could plausibly argue that they had not yet taken the merchandise anywhere that was inconsistent with the scope of their implicit authority as customers.

On this point, we wish to point out that even though a defendant’s physical location when apprehended may be relevant to the issue of whether their exertion of control was unauthorized, physical location is not necessarily determinative. There are other types of conduct that a person can engage in, within the confines of a retail store, that are inconsistent with a customer’s scope of authority. See, for example, State v. T.F., 2011 WL 5357814 (Wash.App.2011), where the Washington Court of Appeals upheld the theft conviction of a defendant whose female accomplice hid an item of merchandise under her clothes, even though the defendant and the accomplice never left the store:

T.F. handed the belt to [the accomplice] R.M., [who,] rather than carrying it in the open, … exerted unauthorized control over the belt by placing the belt under her shirt and starting toward the store’s exit. Concealing the belt in this way was an act inconsistent with the store’s ownership of the item…. On these facts, the trial court could have found that a third degree theft had been committed.

T.F., 2011 WL 5357814 at *2.

Turning to the facts of Simon’s case, we conclude that any technical flaw in the judge’s response to the jury was harmless beyond a reasonable doubt.

As we have explained, there was a dispute in Simon’s case as to precisely where Simon was located when he was stopped by the store employee. But under any version of the evidence, Simon had already gone through the check-out line—where he paid for a couple of food items while, at the same time, either hiding or disguising the jacket, the backpack, and the DVDs he had taken—and he was headed toward the exit when he was apprehended.

Even viewed in the light most favorable to the defense, Simon’s conduct constituted the actus reus of theft. His conduct was inconsistent with the scope of possession granted to customers—regardless of whether Simon had reached the outer door, or even the entrance to the vestibule, when he was stopped. Thus, under the specific facts of Simon’s case, the judge’s response to the jury was correct: any variation in the testimony on this point was irrelevant to Simon’s guilt or innocence of theft.

Simon also argues on appeal that the jury instructions on the lesser offense of attempted theft were flawed. Given our resolution of the preceding issue, any error in the jury instructions on attempted theft was harmless.

[…]

Conclusion

The judgement of the superior court is AFFIRMED.

Theft of Marital Property

To commit most forms of theft, the defendant is required to obtain property of another. Property of another means property that the defendant is not privileged to infringe. AS 11.46.990(6). You cannot steal your own property, but it is no defense that the property stolen was previously stolen (i.e., the victim was himself a thief). Stealing from a thief is still theft.

But what about jointly owned property, like marital assets? Marital assets include all property earned by either spouse during the marriage. The property, even if earned by one spouse, is owned jointly with the other spouse. Under Alaska law, commonly held property of a married couple constitutes “property of another,” even as between two spouses. Thus, a spouse can steal property from a co-spouse, if they do so with the intent to permanently deprive the spouse of the property. However, such a case is rare. As the Court of Appeals noted in LaParle v. State, 957 P.2d 330 (Alaska App. 1998),

This is not to say that a husband or wife commits theft whenever they spend funds from a joint checking account without the other spouse’s knowledge or permission, or whenever they use common funds to make a purchase or an investment that the other spouse does not approve of. Before a husband or wife can be convicted of stealing marital property, [Alaska law] requires the government to prove that the defendant “[was] not privileged to infringe” the other spouse’s interest. In most instances, both spouses have equal right to possess, use, or dispose of marital property. Thus, one spouse’s unilateral decision to draw funds from a joint checking account or to give away or sell a marital possession normally will not constitute theft, because the actor-spouse will have had a privilege to infringe the other spouse’s interest in the property.

See id. at 334.

Property Subject to a Security Interest

With regard to property subject to a security interest, the code provides that the person in lawful possession of the property shall have the superior right of possession. This is true even if legal title lies with the holder of the security interest pursuant to a conditional sales contract or security agreement. Although this sounds hyper-technical, in essence, unless there is an agreement to the contrary, such as a sales contract, the legal owner of a vehicle (e.g., bank) cannot repossess the vehicle from the registered owner for failure to make payments without first seeking a writ of assistance from the court. Of course, if the sales contract provides for a right of non-judicial repossession, then the legal owner need not seek court intervention.

Theft of Lost or Mislaid Property

The second theory of theft is theft of lost or mislaid property. AS 11.46.160. If a defendant obtains property in a manner knowingly that the property is lost, mislaid, or delivered by mistake, the person is guilty of theft. The defendant must have the specific intent to permanently deprive the rightful owner of the property and fail to make reasonable efforts to find the owner. Reasonable efforts include notifying the property owner or law enforcement.

Example of Theft of Lost or Mislaid Property

John receives a check from his friend for $10. John goes to the bank and cashes the check. The teller inadvertently gives John $100 (as opposed to $10). Once John knows of the mistake, he is required to return the $90. If John takes steps to deprive the bank of the money (by hiding it under his porch), he may be prosecuted for theft.

Theft by Deception

Theft by deception is similar to the common law crime of false pretenses. AS 11.46.180. Some states refer to this crime as Larceny by Trick. At common law, a person committed the crime of false pretenses if the person obtained title and possession of property by making a false representation about a material fact with the intent to defraud the property owner. The gravamen of false pretenses was the uttering of a deliberate factual misrepresentation to obtain property. The revised code focuses on deception. Deception covers a broad range of conduct designed to create a false impression intended to obtain property. AS 11.81.900(b)(18). For example, a defendant is guilty of theft by deception if they befriend an older adult and tell the person a series of lies in an effort to obtain their money. See e.g., Linne v. State, 674 P.2d 1345 (Alaska App. 1983). Prosecutions of elder fraud can be grounded in this theory of theft.

Theft by Receiving

Theft by receiving, the fourth theory of theft, occurs if a person buys, receives, retains, conceals, or otherwise disposes of stolen property with reckless disregard that the property was stolen. AS 11.46.190. Within the criminal milieu, this person is commonly referred to as a fence – a person who knowingly buys and sells stolen property. But for criminal liability to attach, the defendant need not “know” that the property was stolen. If the defendant consciously disregards an unjustifiable risk that the property is stolen (i.e., recklessness), the defendant is guilty of theft. Receiving is broadly defined and includes acquiring possession or title to the property. The actus reus of the theory is the retaining of stolen property. A defendant who innocently takes possession of stolen property, unaware that it has been stolen, and later learns the true origins of the property is guilty of theft at the moment they retain the known stolen property. See Saathoff v. State, 991 P.2d 1280 (Alaska App. 1999) affirmed 29 P.3d 236 (Alaska 2001). In essence, theft by receiving is not a continuing offense. The theft is complete once the defendant decides to keep an item aware that it is stolen.

Example of Theft by Receiving

George needs a new flat screen television for his apartment. George buys a large, 4K ultra-flat screen television from a guy in an alley for $50. (Similar televisions retail at $2000 brand new). The guy won’t tell George his name, won’t tell him where the television came from, and tells George to ignore the “Property of UAA” sticker that is on the back of the television. In this example, George is guilty of theft by receiving if he decides to buy the television. George acted recklessly when he purchased the television.

Theft of Services

Recall that personal services are different than real or personal property. Personal services include such things as labor, professional services, transportation (such as a taxi ride), telephone service, entertainment, food, and lodging. Theft of services includes obtaining services by deception, force, theft, or other means of avoiding payment for the services. AS 11.46.200. For example, improperly connecting to a video streaming service (e.g., Netflix®) would be theft of services, even if you never watched a single Netflix® show. Cruz-Reyes v. State, 74 P.3d 219 (Alaska App. 2003). It also includes absconding without paying for a hotel, restaurant, or other similar services, and such conduct is prima facie evidence that the services were obtained by deception. Theft of services includes when a person improperly diverts services under their control to their benefit. For instance, the foreman of a painting crew who has his subordinates paint his house on company time. The foreman is guilty of theft of services.

Theft by Failure to Make Required Disposition of Funds Received or Held

The final theory of theft covers the situation where a person receives property by promising to dispose of it in a certain way and fails to fulfill the obligation. Typically, this occurs when an employer withholds specific amounts of money from an employee’s paycheck for taxes and fails to pay the necessary taxes, and instead simply keeps the money for the employer’s own benefit.

Determination of Value

Because the value of the property stolen is critical for determining which degree of theft has been committed, and consequently the penalty, Alaska law specifies how to determine value. Value generally means the market value of the property, or if that cannot be ascertained, the replacement cost of the property. Further, if a series of thefts is committed “under one course of conduct,” the thefts are aggregated (added together) to determine the total value. AS 11.46.980.

Example of Aggregation

A police officer apprehends a fence (an individual who knowingly purchases stolen property and then resells the items to others), and the investigation proves that the fence purchased the stolen items from the same person over a relatively short period of time. If the stolen items have individual values of $100, $200, $500, and $400, the defendant can be charged with felony theft since the total value of the property was $1200 (remember that felony theft is any theft over $750). The property values can be aggregated.

Theft From the Person (Purse Snatching)

Recall that there are circumstances in which the distinction between robbery and theft is fuzzy. Robbery requires more than “incidental or minimal” force. A defendant who intentionally bumps into a person in an effort to distract the victim from a surreptitious theft does not commit the crime of robbery. Instead, if the property is taken “from the person of another,” the defendant is guilty of second-degree theft. The law treats non-forcible thefts (i.e., pickpocketing) as felony theft, regardless of the value of the stolen property, in part because of the danger associated with using any force to accomplish a theft. AS 11.46.130(a)(3). A purse snatching constitutes felony theft, not felony robbery, unless the amount of force used was non-minimal.

Non-Consolidated Theft Offenses

In addition to consolidated theft offenses (discussed above), the code also includes several crimes that appear similar to theft on their face, but are used to prosecute specific circumstances. For example, the code criminalizes issuing a bad check. AS 11.46.280. A person commits the crime of issuing a bad check if the defendant knows that it will not be honored by the bank. This statute does not require the defendant act with the intent to defraud or that the defendant actually obtain the property. A detailed examination of the various non-consolidated theft offenses is beyond the scope of this book. Alaska’s non-consolidated theft offenses can generally be found in 11.46 et. seq.

Vehicle Theft

One non-consolidated theft offense that frequently arises is vehicle theft. Alaska has two degrees of vehicle theft due to the unique circumstances that arise with vehicle thefts. Compare AS 11.46.360 and 11.46.365. First-degree vehicle theft covers those situations we typically think of as “traditional” vehicle theft – that is, a person who takes another person’s vehicle without permission. It also covers less common conduct. Joyriding – the temporary taking of a vehicle without the owner’s consent, but without the intent to permanently deprive the owner of the property – is first-degree vehicle theft. See Allridge v. State, 969 P.2d 644 (Alaska App. 1998). The key to first-degree vehicle theft is that the initial taking must be trespassory. A person who lawfully “borrows” a car, but fails to return it, is not guilty of first-degree vehicle theft. (Although such conduct may constitute second-degree vehicle theft, discussed below.) See Eppenger v. State, 966 P.2d 995 (Alaska App. 1998). First-degree vehicle theft is a felony whereas second-degree vehicle theft is a misdemeanor.

A person who lawfully obtains a vehicle, but retains it beyond the period of time authorized, is guilty of a less serious vehicle theft: second-degree vehicle theft. AS 11.46.365. This occurs most commonly when a person fails to return a car pursuant to a commercial rental agreement, or fails to pay a debt on a rental car.

You be the Judge …

Brockman visited Alaska Pacific Leasing, a company that leases and sells trucks and other heavy equipment. Brockman told the salesperson that he was in the market for a new truck, and he indicated he was interested in a 2004 GMC pickup. Brockman discussed financing terms with the salesperson and asked if he could test drive the truck. The salesperson photocopied Brockman’s driver’s license and then gave him the keys so he could take it for a test drive. Brockman drove away in the truck.

Eight days later, the truck was found parked outside the locked gate of Alaska Pacific Leasing. The truck was slightly damaged, had trash inside, and had three thousand additional miles on it. Brockman was charged with first-degree vehicle theft. Was Brockman appropriately charged with vehicle theft? Why or why not. Check your answer at the end of the chapter.

Forgery and Related Offenses

Both at common law and under the revised criminal code, the crime of forgery is separate from the crime of theft. Forgery is the creation of a false legal document (or a material modification of an existing legal document) with the intent to defraud another person. The key to common law forgery was that the false document, created with the intent to defraud, had legal significance (if the document had been genuine). Common law also recognized the related crime of uttering if the false document was presented to the victim as authentic with the intent to defraud.

The revised criminal code divides the crime of forgery into three degrees, which cover different methods of creating, possessing, and passing forged written instruments. The dividing line between the degrees of forgery is not the dollar amount or value impacted, but the kind of document involved.

Any written instrument may be the subject of forgery. A written instrument includes any written or printed matter used for the purpose of conveying evidence of value, right, privilege, or identification. A driver’s license, stock certificate, or deed falls within the definition. AS 11.46.580(b)(3).

Forgery requires the defendant act with an intent to defraud culpable mental state. Intent to defraud includes “an intent to injure someone’s interest which has value, or an intent to use deception.” AS 11.46.990(11)(A). Included within this definition is a forger who passes the forged instrument as long as he knows that he is facilitating an eventual fraud – i.e., selling forged stock certificates that are represented to be forged, to a third person who intends to pass them as genuine.

Forgery normally requires the person to make, complete, or alter a written instrument. Drawing a check and signing someone else’s name would constitute “falsely making” a written instrument. A person who merely signs someone’s name to a check that has already been drawn “falsely completes” a written instrument. The person who changes a check made out for five dollars to five hundred dollars by adding the word hundred “falsely alters” the instrument. All three scenarios constitute forgery. The alteration must be a material one, however. Simply adding a person’s middle initial to a signature would not ordinarily be forgery absent evidence that such an alteration is significant.

Alaska has incorporated the common law crime of uttering into the modern crime of forgery. AS 11.46.510. Now uttering a forged instrument is included within the definition of third-degree forgery. Utter includes all methods of making use of a forged instrument, such as issuing, transferring, circulating, or tendering. Thus, the person creating the forged document and the person using the forged document are both guilty of forgery.

The law elevates forgery to a low-level felony if the forged written instrument is an instrument that conveys a legal right, such as a will, contract, negotiable instrument, or promissory note. If the instrument is a valuable government instrument, then the law elevates the forgery to a class B felony offense.

Alaska has also created several specific crimes surrounding a person’s intent to defraud a victim. A detailed discussion of the offenses is beyond the scope of this book. Each offense focuses on a different method of fraud. For example, criminal simulation criminalizes a fraudulent misrepresentation about antique or rare objects. This occurs when someone attempts to sell an object claiming that it is very old or made by a particular person. AS 11.46.530. Criminal impersonation, on the other hand, is aimed at a person who, with the intent to defraud, assumes a false identity or falsely claims to be someone else. AS 11.46.565. Both, like all forgery offenses, require the prosecution to prove that the defendant acted with a specific intent to defraud the victim.

White-Collar Crimes

White-collar crimes normally fall within the category of business and commercial offenses. White-collar crimes are frequently complex because of their nature. Criminal investigations usually take months or years, and involve close cooperation between various law enforcement agencies and the prosecutor’s office. White-collar criminal investigations are not built quickly. They require significant analysis of documents and the deceptive behavior of suspects. Although such conduct is complex and difficult to investigate, white-collar criminal statutes allow for the prosecution of sophisticated criminal enterprises.

For example, the crime of scheme to defraud covers large-scale fraudulent schemes involving five or more victims or large amounts of money. AS 11.46.600. Similar to the federal mail fraud statute, the statute is used to prosecute large-scale consumer frauds. Courts interpret scheme broadly. The scheme may include trickery, deceit, half-truths, concealment of information, and affirmative misrepresentations. The fraud must be more than mere puffery, but it covers a calculated scheme designed to deceive people of ordinary prudence and comprehension even though no misrepresentation was made. Victims are not required to suffer a particular dollar loss; any monetary loss is sufficient to invoke the statute provided it involved more than five victims.

Example of Scheme to Defraud

Edward Byford was convicted of scheme to defraud for defrauding nine people over the course of two and half years by promising to build log homes for the victims. Byford would show the unsuspecting victims photographs of beautiful log cabins that he had never built. Byford asked the victims to pay him substantial portions of the money up front (hundreds of thousands of dollars) for buildings that never materialized. In addition to taking the victims’ money up front, Byford refused to refund any money to the victims. Byford was convicted of scheme to defraud; his convictions were upheld on appeal. See Byford v. State, 352 P.3d 898 (Alaska App. 2015).

Federal Mail Fraud Statute

The federal mail fraud statute has been used to punish a wide variety of schemes, including Ponzi schemes, like the high-profile prosecution of Bernie Madoff. In a Ponzi scheme, the defendant informs investors that their investment is being used to purchase fictional real estate, stocks, or bonds, when in reality, the money is appropriated by the defendant to pay earlier investors. Eventually, this leads to the collapse of the enterprise and results in significant losses to the investors.

Other Commercial Fraud Crimes

Criminal statutes also punish misapplication of property (frequently used to prosecute attorneys for stealing from their clients), falsifying business records (the preparatory action in anticipation of fraud), and deceptive business practices (criminal violations of the Consumer Protection Act), among others. In essence, all of the statutes criminalize specific acts of “white collar” fraudulent behavior. See 11.46.600 et. seq.