Drugs and Alcohol

The Alaska code includes several crimes that are often viewed as victimless and harmless (other than the harm done to the defendant or society in general). Specifically, Alaska has criminalized conduct surrounding drugs, alcohol, prostitution, and gambling. Drug offenses criminalize the manufacture, delivery, sale, and possession of various drugs. Alcohol offenses criminalize conduct involving the sale, possession, and delivery of alcohol. Alaska regulates alcohol to a greater extent than most states. Prostitution, pimping, and pandering (now referred to as sex trafficking) criminalize “consensual” sexual activities. Finally, the code criminalizes specific types of gambling. Each of these crimes violates society’s collective morality.

Drug Policy

The American criminal justice system has long punished the use of intoxicating substances deemed harmful to the human body. From Prohibition in the 1920s to the War on Drugs beginning in the 1960s, the criminal justice system has been at the forefront of society’s response to the negative consequences of the use of illicit drugs and alcohol. Nearly every community has been impacted. Alaska has been no exception.

A complete discussion of the efforts to combat illicit drug trafficking is beyond the scope of this textbook. Broadly speaking however Alaska’s statutory scheme seeks to reduce the availability of drugs through various enforcement and interdiction methods, including the prosecution of both drug traffickers and drug users. While policymakers may face criticism for criminalizing drug use, Alaska is not unique in its efforts. But Alaska does treat traffickers differently from users.

Alaska grades drug offenses based on the type of drug involved and the conduct the defendant engaged in. For example, a person who sells heroin to a minor is guilty of an unclassified felony, whereas a person who simply possesses cocaine for personal use is guilty of a misdemeanor. Compare AS 11.71.010 and 11.71.050. Alaska’s statutory scheme relies on the interplay between these two components.

Drug Schedules

Controlled substances (drugs) are divided into categories, called schedules, based on how dangerous the drug is. The schedules contain both illicit drugs (e.g., “street drugs”) and non-illicit drugs (e.g., prescription drugs). All controlled substances are classified into one of six schedules, which are labeled schedules IA through VIA. AS 11.71.140 – AS 11.71.190. The scheduling of substances is patterned after the federal drug schedules, which classify substances into five schedules, labeled I through V. See 21 U.S.C. §812. Alaska has adopted the letter “A” after its numbered schedules to clearly distinguish between state and federal schedules.

Although both the federal government and Alaska classify substances based on similar criteria: a substance’s potential for abuse, its biomedical hazard, its likelihood of dependence, and its relationship to criminal activity – the jurisdictions weigh the factors very differently. As a result, the schedules are not identical and contain some significant differences. For example, under federal law, Schedule I includes drugs that have “no currently accepted medical use”. 21 U.S.C. §812(b)(1)(B). Alaska has specifically omitted this criterion.

In Alaska, the more dangerous a drug is, regardless of medical use, the higher it is placed on the drug schedules. For example, fentanyl is a powerful painkiller, and doctors frequently prescribe it during childbirth and for end-of-life pain management. Fentanyl is a synthetic opiate and can be lethal if taken in excess. It is also highly addictive. Alaska classifies it as a Schedule IA controlled substance along with all opiates and opiate derivatives. AS 11.71.140(c)(29). Methamphetamine, on the other hand, currently has no medical use, and is seen almost exclusively in illegal drug trafficking. Although methamphetamine is dangerous, it does not have the same potential for abuse as opiates. It is classified as a Schedule IIA controlled substance. AS 11.71.150(e)(2). Understanding the relevant drug schedules is very important, as it directly ties to the seriousness of the criminal behavior.

One very significant difference between the federal and state schedules is marijuana. The federal government classifies marijuana as a Schedule I controlled substance (the highest and most dangerous level of drug) because of its lack of accepted medical use. Federal law criminalizes the possession of any amount of marijuana. 21 USC § 844. Alaska, on the other hand, classifies marijuana as a Schedule VIA controlled substance (the lowest level) because state lawmakers have found it to be the least dangerous drug. Alaska permits a person 21 years or older to lawfully purchase and possess marijuana. AS 17.38.020.

Drug Trafficking versus Drug Possession

A drug’s placement on the drug schedules is just one component of understanding Alaska’s drug statutory scheme. The second component involves the defendant’s conduct. Broadly speaking, the law criminalizes two types of conduct associated with controlled substances: drug possession and drug trafficking. Possessory offenses are generally graded lower; trafficking offenses are generally graded higher.

Possessory offenses, as the name implies, criminalize the possession of a controlled substance for personal use. Recall that possession can take several forms, including both actual and constructive possession. Actual possession occurs when a controlled substance is found in an individual’s physical or immediate presence. Constructive possession occurs when an individual is not in physical possession of an item but has the authority (legal or otherwise) to control an item. See Alex v. State, 127 P.3d 847 (Alaska App. 2006).

Is Evidence of Drug Use Evidence Drug Possession?

In 1989, police executed a search warrant at a suspected crack house. Police found Earl Thronsen lying face down on a couch in the living room. His hands were concealed beneath him. When officers placed Thronsen in handcuffs, officers found a syringe underneath his arms. The syringe was consistent with intravenous drug use, as were Thronsen’s track marks on his arms.

Pursuant to a search warrant, police obtained samples of Thronsen’s blood and urine. The urine tested positive for the presence of cocaine and cocaine metabolites. The Grand Jury indicted Thornsen for possession of cocaine “in his body.” Thronsen challenged the indictment, arguing that the presence of a controlled substance in a person’s body is insufficient evidence to prove the person possessed the drug.

Can a person be convicted of drug possession based on evidence that the person had previously ingested drugs? Why or why not? Check your answer at the end of the chapter.

Although exceptions exist, normally first-time offenders found in possession of controlled substances (other than marijuana) are guilty of a misdemeanor. AS 11.71.050(a)(4). Colloquially, this is referred to as simple possession. By classifying first-time possession as a misdemeanor, the legislature has emphasized rehabilitation and treatment over other penological goals. At least theoretically, the criminal justice system treats users as individuals with a disease in need of intervention. The legislature has sought to avoid the collateral impacts normally associated with a felony conviction. First-time defendants convicted of simple possession are not hardened criminals in the eyes of the criminal code.

As one can imagine, these sentencing goals change with repeat offenders. A second-time offender is no longer guilty of a misdemeanor. If the defendant has been previously convicted of simple possession in the previous 10 years, the crime is elevated to a felony. AS 11.71.040(a)(12).

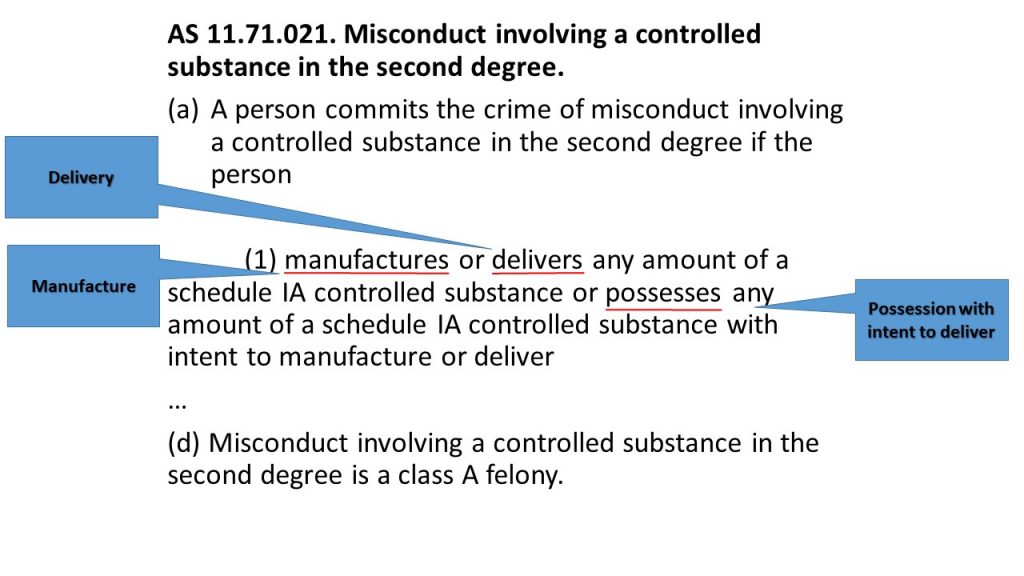

Drug trafficking is a much more serious offense. The code criminalizes three separate voluntary acts associated with trafficking: the manufacture of a controlled substance, the delivery of a controlled substance, and possession of a controlled substance with the intent to distribute. Each action is a component of a successful drug trafficking operation and the legislature seeks to punish each one. A typical drug trafficking statute, like AS 11.71.021(a)(1), includes all three.

Figure 11.1 – Alaska Criminal Code – AS 11.71.021(a)(1)

Notice that the subsection does not require the defendant to manufacture, deliver, or possess a certain amount of the controlled substance. Any amount is sufficient to impose criminal liability. Quantity is not an attendant circumstance in this subsection. The statute criminalizes the action, independent of the amount trafficked. You will see momentarily, the quantity trafficked is a sentencing issue, not a liability issue.

Manufacturing a controlled substance includes producing, preparing, converting, growing, or processing a controlled substance. AS 11.71.900(13). Simply put, any change to a drug or its precursors will likely be sufficient to demonstrate manufacturing. Thus, converting cocaine hydrochloride (powder cocaine) into crack cocaine (by neutralizing the hydrochloride so it is no longer water-soluble) constitutes “manufacturing.” See Chamber v. State, 881 P.2d 318, 321 (Alaska App. 1991). This is true even though the basic cocaine molecule does not change during the process.

Delivery means the actual or constructive transfer of the controlled substance to another person. AS 11.71.900(13). The law does not require remuneration or an established agency relationship (i.e., dealer/user). A defendant is guilty of trafficking even if the defendant gives a controlled substance to another person for benevolent reasons. For example, if a person shares their prescription oxycodone (a powerful painkiller and schedule IA narcotic) with an injured friend during a camping trip, the person is guilty of drug trafficking under AS 11.71.021(a)(1). To avoid criminal liability, the person could assert the affirmative defense of necessity, but the person would have to demonstrate that there was no reasonable alternative. AS 11.80.320. In short, the law is not limited to drug dealers; any transfer of a controlled substance without a prescription is criminalized. Conversely, a drug purchaser (i.e., a user) may not be prosecuted or convicted of trafficking as an accomplice to the delivery. See e.g., Howard v. State, 496 P.2d 657, 660 (Alaska 1972). In other words, drug users are not facilitating the delivery of drugs when they purchase the drugs.

Possession with the intent to deliver or manufacture is the most common theory of drug trafficking prosecutions. The theory does not require evidence of actual manufacturing or actual delivery, but instead, focuses on the defendant’s intent. If the defendant possessed a controlled substance with the intent to subsequently deliver it, the defendant is guilty of drug trafficking. The line between drug trafficking and simple drug possession is not always clear, however; in fact, it is often blurry. The jury considers the totality of the circumstances in determining whether the defendant possessed the drugs with the intent to deliver, including the quantity, value, and associated drug paraphernalia. Although no one fact is determinative, possession of a large quantity of drugs, especially when the amount is larger than typically used for personal use, frequently demonstrates that the defendant is a dealer and not a user. See e.g., Stacy v. State, 500 P.2d 1023 (Alaska App. 2021). The government frequently relies on expert testimony to explain to the jury what constitutes indicia of drug distribution as opposed to personal use. Such experts are typically drug investigators, which may be qualified as hybrid experts in court. See id.

Alaska law distinguishes between low- and high-level traffickers through the application of aggravating and mitigating factors. An aggravating factor applies when a large quantity of a controlled substance is involved, and a mitigating factor applies when a small quantity of a controlled substance is involved. AS 12.55.155(c)(23)-(c)(26); 12.55.155(d)(13)-(d)(15). These factors allow the court to depart upwards or downwards from the felony presumptive-range sentence that would be imposed absent an aggravating or mitigating factor. Whether a quantity is determined to be large or small is fact-driven and looks at several variables:

Within any class of controlled substance, what constitutes an unusually small or large quantity may vary from case to case, depending on variables such as the precise nature of the substance and the form in which it is possessed, the relative purity of the substance, its commercial value at the time of the offense, and the relative availability or scarcity of the substance in the community where the crime is committed. Variations may also occur over time: what amounted to a typical controlled substance transaction ten years ago might be an exceptional one today. These variables do not lend themselves to an inflexible rule of general application, and they render it both undesirable and wholly impractical to treat the question of what constitutes a “large” or “small” quantity . . . as an abstract question of law. The question must instead be resolved by the sentencing court as a factual matter, based on the totality of the evidence in the case and on the court’s discretion, as informed by the totality of its experience.

See Knight v. State, 855 P.2d 1347, 1349-50 (Alaska App. 1993).

Marijuana

Marijuana is largely legal under Alaska law and regulated similarly to alcohol. Following a 2015 ballot initiative, Alaska legalized the manufacture, distribution, and sale of marijuana by licensed marijuana establishments. The marijuana industry is heavily regulated by the state’s Marijuana Control Board. The state’s criminal statutes surrounding marijuana largely target the marijuana “gray market” – that is, the unlawful cultivation, distribution, and possession of unregulated marijuana.

The legalization of marijuana presents interesting constitutional dilemmas given that federal law continues to list marijuana as a Schedule I drug and does not permit its possession, use, or sale for any person. Thus, Alaska’s laws surrounding the recreational and medical use of marijuana potentially violate the Supremacy Clause in the federal Constitution. That said, the US Supreme Court has not invalidated any state’s marijuana statutory scheme on this basis. The Court has upheld Congress’s authority to prohibit the possession and use of small quantities of marijuana under the Federal Controlled Substances Act, however, and has rejected a medical necessity exception for the possession and use of marijuana. See Gonzales v. Raich, 545 U.S. 1 (2005); United States v. Oakland Cannabis Buyers’ Cooperative, 532 U.S. 483 (2001).

Alcohol

The debate surrounding the dangerousness of alcohol – and the government’s role in a solution – has mutated over the past century. For example, in 1919, and for largely puritan reasons, an overwhelming majority of states ratified the 18th Amendment prohibiting alcohol in the United States. Over the next 14 years, both federal and state law enforcement officers dedicated significant time and resources to its enforcement. Fourteen years later, prohibition was repealed through the passage of the 21st Amendment. While a more laissez-faire scheme took hold surrounding the possession of alcohol, the government remained intimately involved in alcohol’s manufacture and distribution.

Alcohol remains a heavily regulated activity. At the federal level, both the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (ATF) regulate interstate and foreign commerce of alcohol. At the state level, the Alaska Alcohol Beverage Control Board (ABC) regulates the manufacture, sale, and possession of alcohol within the state. State law defines the legal drinking age, licensing requirements, and possession limitations. See e.g. AS 04. et.seq. For example, it is illegal to sell, give, or barter an alcoholic beverage to an intoxicated person. AS 04.16.030(a)(1). Likewise, it is illegal for a person to remain in a bar if they are intoxicated. AS 04.16.040. Although the ABC Board regulates the industry, violation of state law results in criminal liability.

Unique to Alaska, Alaska law allows local municipalities to enact local option laws that prohibit the sale, importation, or even possession of alcohol within a community. AS 04.11.499. Violation of a community’s local option law is significant – it is a felony to import alcohol into a municipality if the community has prohibited such conduct. AS 04.16.200(b).

What’s in a name…

Colloquially, a municipality that has passed an ordinance to ban the importation, sale, or possession of alcoholic beverages is called dry; a community that allows limited amounts of alcohol, or under specific circumstances, such as for personal use, is called damp. Finally, a community with limited or typical alcohol regulations – like Anchorage – is referred to as wet.

Public Intoxication

Recall that it is unconstitutional to punish a person for being addicted to drugs or alcohol. Robinson v. California, 370 U.S 660 (1962). A person’s addiction relates to their status in the community. Status is not a criminal act.

While the government may not criminally punish a person for their addiction, police frequently place individuals who are severely intoxicated into protective custody. Such police actions are not part of an officer’s criminal enforcement function, but instead part of an officer’s community caretaker function. Society has determined that severely intoxicated individuals need supervision, and in some circumstances, medical intervention.

When an officer encounters a person who is intoxicated – that is, substantially impaired as the result of alcohol or drugs – the law permits the officer to take the person into custody until the person is sober. AS 47.37.170(a). However, if a person is so intoxicated that they are incapacitated – that is, incapable of making rational decisions as a result of alcohol or drugs – police must take the person into protective custody. AS 47.37.270(7). Police have a mandatory duty to take incapacitated persons into protective custody. AS 47.37.170(b).

Example of Protective Custody

Sam recently received fantastic news. He received an “A” on his Criminology final exam. In an effort to celebrate, Sam and a couple of his friends decide to go out after school for drinks and merriment. After a long night of drinking, Sam stumbles out of the bar and begins walking home. Sam doesn’t make it far. About three blocks from the bar, Sam finds a park bench and lies down. Sam quickly passes out on the park bench. Sam’s friends are nowhere to be found. Sam is alone. About 20 minutes later, an officer happens upon Sam passed out on the bench. The officer rouses Sam and begins asking him questions. Sam is incoherent. He is unable to answer the officer’s questions and unable to tell the officer where he lives and how he plans to get home. If the officer determines that Sam is intoxicated, the officer may take Sam into protective custody and transport him to a detention facility (jail) until Sam is sober. On the other hand, if the officer determines that Sam is incapacitated, the officer is required to take Sam into protective custody. The officer does not have the discretion to let Sam stay on the park bench.