Weapon Offenses

From drive-by shootings to brass knuckles, Alaska weapon offenses cover a wide array of misconduct. Some are serious and some are relatively minor. One constant is that they all involve a “weapon” under prohibited circumstances. Not all weapons are equal, however: some are inherently deadly (e.g., a firearm), some are only dangerous if used in a particular manner (e.g., bear spray), and some are relatively common (e.g., a steak knife).

Weapon offenses share a second commonality. Under Alaska law, there is no “victim” to a weapon offense. While a person may be seriously injured as a result of a weapon, the harm is punished under other criminal code provisions (namely, assault). Weapon offenses do not penalize the resulting harm, injury, or damage. They penalize the danger created by the weapon.

This chapter does not attempt to analyze each different weapon statute. Given the sheer amount of misconduct that is covered it is difficult to summarize beyond simply outlining the individual statutes. Instead, this chapter explores some key categories of the various types of conduct that constitute Misconduct Involving a Weapon (the name for weapon offenses). You will notice that offenses are graded into five degrees. The most serious is a class A felony, whereas the least serious is a class B misdemeanor. Compare AS 11.61.190 and 11.61.250.

Inherently Dangerous Conduct

In response to the belief that violent gang activity was plaguing Alaskan communities in the 1990s, the Alaska Legislature passed a series of laws designed to increase the penalties associated with the use of firearms. The belief was that criminal street gangs were responsible for significant violence in Alaska’s urban communities, and stiffer penalties for gun use would assist police in stopping the violent behavior.

As noted during the 1996 legislative process,

[The proposed changes were] introduced in response to the rapid escalation of violent gang activity throughout Alaska. [The staff member] noted that the amount of gang related violence [in 1996] and previous. In 1995, there were more than four gang-related murders committed in Anchorage, as well as, numerous gang-related hold-ups and drive by shootings, and other criminal activities by gangs. Present intelligence from the Anchorage Police Department notes that there are over 463 gang members active in Anchorage. The central purpose behind this bill [to amend weapon offenses] is to give law enforcement and prosecutors the tools that they desperately need to deal with the increased presence of gangs in Alaska.

See Minutes from House Judiciary Comm., 1995-1996 Leg., 19th Sess. (Alaska March 27, 1996) (statement of S. Ernouf, staff to bill sponsor).

The most significant change was to Misconduct Involving a Weapon in the First Degree, which created a class A felony offense for discharging a firearm from a motor vehicle under circumstances creating a substantial and unjustifiable risk of injury to another person or damage to property. 11.61.190(a)(2). The statute targets drive-by shootings.

The gravamen of the offense is the danger created by the firearm, not the injury. Drive-by shootings create generalized public danger, regardless of whether a person is struck, injured, or placed in fear. If multiple people are injured or placed in fear by a drive-by shooting, the defendant will likely face punishment for both first-degree weapons misconduct and multiple counts of assault. See e.g., Young v. State, 331 P.3d 1276, 1284 (Alaska App. 2014).

Less serious weapon offenses criminalize shooting from a vehicle under circumstances that do not create a risk of injury or property damage. Misconduct Involving a Weapon in Third Degree, a class C Felony, prohibits the reckless discharge of a firearm from a motor vehicle under circumstances that do not rise to the level of a drive-by shooting. AS 11.61.200(a)(10). This would cover circumstances where a person randomly shoots a firearm into the air while driving. While such conduct is still extremely dangerous and unnecessary, the shooting is not done to instill fear or injury.

Misconduct Involving a Weapon in the Fourth Degree, a misdemeanor, prohibits shooting from, on, or across a highway. AS 11.61.210(a)(2). It also prohibits a person recklessly discharging a firearm that creates a risk of injury or damage to property. AS 11.61.210(a)(3). The statute is similar to reckless endangerment: it does not require that injury or damage occur. Whereas first-degree weapon misconduct is targeted at particular conduct – i.e., drive-by shootings – these lesser offenses penalize serious, but less dangerous behavior.

To further combat gang violence, the Alaska legislature created a subsection within Misconduct Involving a Weapon in the Second Degree that prohibits knowingly discharging a firearm in the direction of a building or dwelling. AS 11.61.195(a)(3). The law intended to ensure punishment for shooting at a house regardless of whether the house was occupied. See Minutes from Senate Judiciary Comm., 1997-1998 Leg., 20th Sess. (Alaska March 26, 1997) (sponsor statement). Unlike first-degree weapon misconduct, second-degree weapon misconduct neither requires proof that the shooting created a substantial risk of injury or death nor shooting from a vehicle.

As you review these statutes notice how they collectively punish the danger associated with the intentional or reckless discharge of firearms. Whenever a firearm is used there is a risk of an errant bullet causing injury, damage, or even death. It is a fundamental rule of gun safety. It is all inherently dangerous, but punishment is graded based on the level of risk the defendant’s conduct creates.

Drugs and Guns

Illegal drug trafficking, and the underworld in which it thrives, functions on fear and the threat of violence, at least in the eyes of the Alaska Legislature. Firearms are the drug dealer’s tool of choice, and firearms are necessary to protect both product and profit. The legislature has created a specific statutory scheme that severely punishes individuals who use or possess a firearm during a felony drug offense. These so-called drug and gun laws target the dangerous relationship between firearms and drug trafficking. Using or possessing a gun during a felony drug offense substantially increases the risk of death or serious physical injury for already dangerous conduct.

The first-degree weapon misconduct statute penalizes the use of a firearm during a felony drug offense. Possession of a firearm during a felony drug offense constitutes Misconduct Involving a Weapon in the Second Degree. Compare AS 11.61.190(a)(1) and 11.61.195(a)(1). This distinction is significant. First-degree weapons misconduct is a Class A felony, punishable up to 20 years imprisonment, whereas second-degree weapon misconduct is a Class B felony, punishable up to 10 years imprisonment.

Misconduct Involving a Weapon in the Second Degree contains two important limitations before authorizing punishment for “simple gun possession” during a drug offense. First, the code only criminalizes firearm possession during a felony drug offense. Misdemeanor drug offenses are excluded from the statute. Thus, it is generally not illegal for a defendant to possess a firearm while at the same time possessing personal use amounts of drugs. See e.g., AS 11.71.050(a)(4)

Second, the law requires a nexus between the firearm possession and the felony drug offense. The “mere” possession of a firearm during a drug offense is insufficient. Collins v. State, 977 P.2d 741 (Alaska App. 1999). Firearms are particularly common in Alaska, and many Alaskans possess firearms to protect their homes and provide for their families. The Legislature did not intend to criminalize personal home protection firearms simply because a person may also be engaged in a felony drug offense. Murray v. State, 54 P.3d 821, 825 (Alaska App. 2002).

To prove a nexus between the firearm possession and the felony drug offense, the government must establish the defendant’s possession of the firearm furthered the felony drug offense in some manner. See Collins, 977 P.2d at 753. The defendant’s possession of the gun must somehow aid, advance, or facilitate the defendant’s overall criminal drug trafficking objective. Multiple factors may be considered, including (1) the type of drug activity conducted, (2) the accessibility of the firearm, (3) the type of firearm, (4) whether the firearm was stolen, (5) the status of the defendant’s possession (legitimate or illegal), (6) whether the firearm was loaded, (7) the proximity of the firearm to drugs or drug profits, and (8) the time and circumstances under which the gun was found. See Murray, 54 P.3d at 824.

The jury is asked to weigh all of these factors, and any additional information, in determining whether the defendant’s possession furthered the drug enterprise or whether the defendant simply possessed a gun in addition to drug trafficking. This determination is fact specific. No one factor is determinative.

Prohibited and Untraceable Weapons

Certain weapons, fully automatic weapons for example, are illegal under both federal and state law. Alaska law classifies such weapons as prohibited weapons. Alaska’s law is patterned after the National Firearms Act. The statute prohibits the manufacture, possession, transportation, sale, or transfer of a prohibited weapon. AS 11.61.200(a)(3). Prohibited weapons include rockets, bombs, silencers/suppressors, automatic weapons, sawed-off shotguns, or grenades. AS 11.61.200(h)(1). In the eyes of the Alaska legislature, “[s]uch weapons have little or no legitimate function, are unnecessary for protection, and are not commonly used for commercial or recreational purposes.” See commentary from Senate Journal Supp. No. 47 at 100-122. Prohibited weapons are used in furtherance of crime and create a substantial – and unnecessary – risk of harm to others. Two important exceptions exist: first, weapons registered under the National Firearms Act are exempt. AS 11.61.200(c). Second, police officers acting within the scope and authority of their employment are exempt from prosecution. Thus, if a law enforcement agency has authorized an officer to use an otherwise prohibited weapon – e.g., a grenade – the officer is exempt from prosecution. AS 11.61.200(e).

Individuals are also prohibited from removing or destroying a firearm’s serial number with the “intent to render the firearm untraceable”. AS 11.61.200(a)(5). The law does not criminalize the possession of a firearm with an obliterated serial number unless the government can prove that the purpose of the altered serial number was to render it untraceable. AS 11.61.200(a)(6). The government normally proves this culpable mental state through police officer expert testimony. See e.g., Collins v. State, 977 P.2d 741, 745 (Alaska App. 1999).

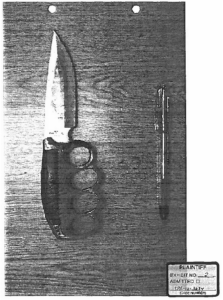

Certain non-firearms are also prohibited, but not at the felony level. Possessing, making, selling, or transferring metal knuckles is a misdemeanor offense. AS 11.61.210(a)(4). Sometimes referred to as brass knuckles, metal knuckles mean “a device that consists of finger rings or guards made of a hard substance and designed, made, or adapted for inflicting serious physical injury or death by striking a person.” AS 11.81.900(b)(37). See Figure 12.2 below.

Figure 9.2 Metal Knuckles

The above photograph was the subject of an appeal in Thrift v. State, 2017 WL 2709732, at *2 (Alaska App. June 21, 2017) where the defendant argued that the above weapon did not constitute “metal knuckles” since a short knife was affixed to the end. Thrift contended that the weapon should be classified as a “knife”. The court rejected Thrift’s argument. “Under Thrift’s interpretation of the statute, the addition of a knife blade to an illegal weapon—a change that makes the illegal weapon even more dangerous—would render the formerly illegal weapon into a legal one. This is illogical.” See id.

Prohibited Persons

Several statutes prohibit certain classes of individuals from possessing weapons, including those convicted of a felony offense, those who are intoxicated, and those who are the subject of a domestic violence protective order. Each class is discussed in turn below.

Felon-In-Possession

Alaska has a relatively unique felon-in-possession law. A convicted felon is only prohibited from possessing a “concealable firearm” or residing in a dwelling where a concealable firearm is stored. AS 11.61.200(a)(1) & (a)(10). At their core, felon-in-possession statutes are anticipatory-type offenses. They seek to prevent harm before it occurs, namely future violent crime. See Davis v. State, 499 P.2d 1025, 1038 (Alaska 1972) reversed on other grounds 415 U.S. 308 (1974).

Given the definition of a firearm, it is immaterial whether the gun is loaded or unloaded, or even functional. AS 11.81.900(a)(1). The weapon must have been designed to discharge a shot by the force of gunpowder; it need not be capable of discharging the shot. A pellet gun, for this reason, is not a firearm, even though it would constitute a “dangerous instrument” for the assault statutes. See generally Kinnish v. State, 777 P.2d 1179 (Alaska App. 1989).

Alaska law does not prohibit felons from possessing all firearms. Only those firearms that are capable of being concealed on the person are prohibited. This unique definition allows Alaskans who have been previously convicted of a felony to possess long guns (e.g., rifles and shotguns) and not be in violation of Alaska law. While this limits the types of firearms that are prohibited, there is no requirement that the firearm actually be concealed on the person. Mere possession of a concealable firearm or residing in a dwelling knowing that there is a concealable firearm present will sustain a conviction. Given the need for long guns in traditional hunting and trapping activities, the legislature recognized that restricting felons from possessing all firearms would be overly restrictive.

The law punishes selling or transferring a concealable firearm to a felon to the same extent it punishes the felon’s possession. AS 11.61.200(a)(2). If a person sells or transfers a firearm capable of being concealed on the person, knowing that the person receiving the firearm is a felon, the transferor is guilty. In the eyes of the law, the person who knowingly transfers a firearm to a felon is “viewed as equally culpable and deserving of identical punishment as the [felon].” See commentary from Senate Journal Supp. No. 47 at 100-122.

A felon who possesses a firearm capable of being concealed while on school grounds or at a child care facility faces an aggravated charge. AS 11.61.195(a)(2). The law elevates the offense to a class B felony (from a class C felony) in this circumstance. This increased punishment is significant, raising the maximum punishment from up to 5 years in jail to 10 years in jail. AS 11.61.195(b).

The Code provides an affirmative defense if the felon has received a pardon, the conviction has been set aside, or if the conviction did not result from any violation of AS 11.41 (crimes against a person) and ten years has elapsed from the date of the defendant’s unconditional discharge. AS 11.61.200(b). A defendant is unconditionally discharged once the defendant is no longer under the care or custody of the Department of Corrections and the defendant has completed any probationary or parole period. AS 12.55.185. As a result, under state law, certain felons are permitted to possess firearms after ten years from their unconditional discharge.

Loss of their right to “bear arms” (as protected under both the federal and Alaska constitutions) is one of the numerous consequences of a felony conviction. Wilson v. State, 207 P.3d 565 (Alaska App. 2009). The statutory prohibition begins the moment the individual is convicted of a felony. Since the status of being a “felon” is an attendant circumstance to the crime, it is not a valid defense that the person did not know felons are prohibited from possessing firearms. See Afcan v. State, 711 P.2d 1198 (Alaska App. 1986). Ignorance of the law is no defense. However, the defendant must know they are a felon (as opposed to a misdemeanant). See Hutton v. State, 305 P.3d 364 rev’d on other grounds 350 P.3d 793 (Alaska App. 2013). A defendant’s genuine belief that their prior conviction was for a misdemeanor may relieve them of criminal liability. This dispute rarely comes up however, since only felons are placed on felony probation and are required to meet with a felony probation officer.

Federal Felon-In-Possession Law

As you have seen, there are significant differences between Alaska and federal law. Felon-in-possession laws highlights another difference. Under Alaska law, a felon is prohibited from possessing a concealable firearm. AS 11.61.200(a)(1). Under federal law, felons are prohibited from possessing any firearm, regardless of type, including ammunition. 18 USC §922(g)(1). This includes long guns and shotguns (which are not considered prohibited weapons under Alaska law). Incidentally, another key significant difference between Alaska and federal law is that federal law prohibits individuals convicted of misdemeanor domestic violence from possessing firearms. 18 USC §922(g)(9). Alaska does not have a corollary provision.

Intoxicated Individuals

Guns and alcohol do not mix. It is a misdemeanor for a person to possess a firearm while under the influence of an intoxicating liquor or drug. AS 11.61.210(a)(1). But the person must be substantially impaired, not merely intoxicated. The law prohibiting possession of a firearm while under the influence of an intoxicating liquor or controlled substance applies equally to all persons and is akin to the prohibition against driving under the influence. See Simpson v. State, 489 P.3d 1181 (Alaska App. 2021).

Although it is a misdemeanor to possess a gun while intoxicated, it is a felony for a person to sell or transfer a firearm to a person knowing that the person is substantially intoxicated. AS 11.61.200(a)(4). If a person gives a gun to an obviously intoxicated person they are guilty of a more serious offense than the person who actually receives the firearm. Compare AS 11.61.200(a)(4) and AS 11.61.210(a)(1).

Individuals Subjected to Protective Orders

Individuals who are prohibited from contacting another person pursuant to a stalking, sexual assault, or domestic violence protective order face additional limitations surrounding the possession of firearms. First, the law prohibits trespassing into a building or onto land in violation of a domestic violence protective order while in possession of “defensive weapon or a deadly weapon, other than an ordinary pocketknife.” AS 11.61.200(a)(8). A domestic violence protective order (DVPO) is an order from the court finding that the petitioner has been the victim of a domestic violence offense by a household member. AS 18.66.100. The order can contain various provisions, but generally includes a “no contact” provision. AS 18.66.100(c)(2). Second, the law criminalizes any in-person communication in violation of a stalking, sexual assault, or domestic violence protective order while in possession of “a deadly weapon, other than an ordinary pocketknife.” AS 11.61.200(a)(9). Both of these provisions recognize the dangers associated with possession of a deadly weapon while violating a protective order. These provisions criminalize otherwise legal weapon possession.

Recall that federal law, unlike Alaska law, prohibits those convicted of misdemeanor domestic violence assault from possessing a firearm. 18 USC §922(g)(9).

Concealed Weapons

Anyone who is 21 years or older and who is legally permitted to possess a firearm (i.e., not a felon), may carry a weapon concealed. Alaska does not require individuals to obtain a permit before carrying a concealed weapon. Although not required, Alaska law allows a person to obtain a carry-concealed permit through the Alaska Department of Public Safety (DPS) if desired. The Alaska Concealed Handgun Permit (ACHP) program allows individuals to carry concealed in sister states that have entered into reciprocity agreements with DPS. AS 18.65.775. This has not always been the law. Previously, Alaska law required all individuals to obtain a carry-concealed permit, the requirement was repealed in 2003. See Ch. 62, SLA 2003, §§ 1, 7.

Although individuals may carry concealed weapons without a permit, Alaska law requires any person contacted by a police officer to immediately inform the officer of any concealed deadly weapons in their possession. Failure to do so is a class B misdemeanor. AS 11.61.220(a)(1)(A)(i). Recall that deadly weapon is broadly defined and includes not just firearms, but also knives, clubs, and similar items capable of causing death or serious physical injury. AS 11.81.900(b)(17). For example, an ordinary steak knife qualifies as a deadly weapon. See Liddicoat v. State, 268 P.3d 355 (Alaska App. 2011). Anyone possessing a deadly weapon concealed on their person must immediately disclose that information when contacted by law enforcement.

The law is intended to protect law enforcement. See Simpson v. State, 489 P.3d 1181 (Alaska App. 2021). Given the dangers associated with police work, requiring individuals to disclose all concealed weapons reduces the likelihood of its surprise use against the officer. The law placed the burden of disclosure on the citizen, not the officer.

The law only requires the person to immediately disclose firearms “concealed on the person”. AS 11.61.220(a)(1). “Concealed on the person” does not include a firearm concealed under the seat of a vehicle, or otherwise hidden in the vehicle. DeNardo v. State, 819 P.2d 903 (Alaska App. 1991). Thus, a driver who fails to inform an officer that a firearm is concealed in the automobile (i.e., under the driver’s seat or in the center console) is not in violation of the law under AS 11.61.220(a)(1). Simply put, “[a] weapon concealed in an automobile is not ‘concealed on the person.'” See DeNardo, 819 P.2d 907.

Explosives

Explosives present a particular type of danger. When used to commit a crime, they allow a perpetrator to avoid detection by being far away from the explosion at the time of detonation. Explosives can also indiscriminately injure numerous unsuspecting victims with relative ease. See e.g., Machado v. State, 797 P.2d 677, 686 (Alaska App. 1990). The law prohibits two forms of conduct involving explosives: criminal possession and unlawful furnishing. AS 11.61.240 and 11.61.250, respectively. The first prohibits the possession of explosives with the intent to commit a crime, whereas the second prohibits the furnishing of explosives to a person knowing that the person to whom they are furnished intends to use the explosives to commit a crime.

Explosives include most chemical compounds, mixtures, and devices that explode, but also include common components used to make explosives and explosive devices, like dynamite, nitroglycerin, and blasting powder. AS. 11.81.900(b)(24). Certain less dangerous items, including firecrackers and small arms ammunition, are expressly excluded.

Criminal Possession of Explosives

If a person possesses or manufactures an explosive substance or device with intent to use the explosive to commit a crime, the person commits the crime of Criminal Possession of Explosives. AS 11.61.240. For example, if a person possesses dynamite with the intent to blow up their neighbor’s storage shed, the person is guilty of Criminal Possession of Explosive. Because this crime criminalizes the possession of explosives (either actual or constructive), the defendant need not actually use the explosive to be held liable. This is true even if the suspect never actually touches the explosive (assuming that the evidence otherwise is sufficient to establish constructive possession). Nore, however, that the culpable mental state is intentionally – the defendant must specifically intend to use the explosive. Possession without a concomitant culpable mental state is not criminal.

The penalty for Criminal Possession of Explosive is similar to the inchoate offenses of attempt and solicitation: punishment is normally one class lower than the target offense. Thus, possession of explosives with the intent to commit a robbery (a class A felony), would be classified as a class B felony. AS 11.61.240(b). Unlike inchoate offenses, the defendant faces liability (and punishment) for both the target crime and criminal possession of explosives. The crimes do not merge. See Machado, 797 P.2d at 686 (upholding convictions for both attempted murder and criminal possession of an explosive when the defendant used a car bomb in an attempt to kill the victim).

Unlawful Furnishing of Explosives

The crime of Unlawful Furnishing of Explosives criminalizes the furnishing of an explosive substance or device to another knowing that the other person intends to use it to commit a crime. AS 11.61.250. Recall that the culpable mental state of knowing is more nuanced than the term is colloquially used. To prove that the suspect acted knowingly, the government is not required to establish that the suspect “positively knew” that the explosive would be used to commit a crime. Instead, the term is used in its legal sense – that is, whether the suspect was aware of a substantial probability that the explosives would be used to commit a crime. AS 11.81.900(a)(2). Knowingly is a lower culpable mental state than intentionally.

The requirement that the defendant “furnishes” the explosive takes into account the multitude of ways in which an explosive substance or device can be transferred from one person to another. It includes selling, giving, mailing, or any other form of exchange. Remuneration is not required. The transfer is sufficient if it is merely moved from one place to another so long as it ultimately ends up in the hands of the person who intends to use the explosive substance or device to commit a crime.

Finally, there is no requirement that the suspect intends to aid the other person in the commission of the target crime. Even if the supplier of the explosive does not want the crime to be committed, if the supplier was aware that there was a substantial probability that the explosive would be used in a crime, then the supplier is liable. Recognize that if the supplier is charged with the target crime under an accomplice liability (AS 11.16.110), then the government must prove that the supplier intended to promote or facilitate the commission of the crime and act with the underlying culpable mental state of the target crime. See e.g., Riley v. State, 60 P.3d 204 (Alaska App. 2002). As you can see, the crime of unlawful furnishing of explosives is much easier to prove than accomplice liability.