6

Impressionism, an introduction

Apart from the salon

The group of artists who became known as the Impressionists did something ground-breaking in addition to painting their sketchy, light-filled canvases: they established their own exhibition. This may not seem like much in an era like ours, when art galleries are everywhere in major cities, but in Paris at this time, there was one official, state-sponsored exhibition—called the Salon—and very few art galleries devoted to the work of living artists. For most of the nineteenth century then, the Salon was the only way to exhibit your work (and therefore the only way to establish your reputation and make a living as an artist). The works exhibited at the Salon were chosen by a jury—which could often be quite arbitrary. The artists we know today as Impressionists—Claude Monet, August Renoir, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot, Alfred Sisley (and several others)—could not afford to wait for France to accept their work. They all had experienced rejection by the Salon jury in recent years and felt that waiting an entire year between exhibitions was too long. They needed to show their work and they wanted to sell it.

The artists pooled their money, rented a studio that belonged to the photographer Nadar, and set a date for their first collective exhibition. They called themselves the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, and Printmakers and their first show opened at about the same time as the annual Salon in May 1874. The Impressionists held eight exhibitions from 1874 through 1886.

The impressionists regarded Manet as their inspiration and leader in their spirit of revolution, but Manet had no desire to join their cooperative venture into independent exhibitions. Manet had set up his own pavilion during the 1867 World’s Fair, but he was not interested in giving up on the Salon jury. He wanted Paris to come to him and accept him—even if he had to endure their ridicule in the process.

Lack of finish

Monet, Renoir, Degas, and Sisley had met through classes. Berthe Morisot was a friend of both Degas and Manet (she would marry Édouard Manet’s brother Eugène by the end of 1874). She had been accepted to the Salon, but her work had become more experimental since then. Degas invited Morisot to join their risky effort. The first exhibition did not repay the artists monetarily but it did draw the critics, some of whom decided their art was abominable. What they saw wasn’t finished in their eyes; these were mere “impressions.” This was not a compliment.

The paintings of Neoclassical and Romantic artists had a finished appearance. The Impressionists’ completed works looked like sketches, fast and preliminary “impressions” that artists would dash off to preserve an idea of what to paint more carefully at a later date. Normally, an artist’s “impressions” were not meant to be sold, but were meant to be aids for the memory—to take these ideas back to the studio for the masterpiece on canvas. The critics thought it was absurd to sell paintings that looked like slap-dash impressions and to present these paintings as finished works.

Landscape and contemporary life

Courbet, Manet and the Impressionists also challenged the Academy’s category codes. The Academy deemed that only “history painting” was great painting. These young Realists and Impressionists questioned the long established hierarchy of subject matter. They believed that landscapes and genres scenes (scenes of contemporary life) were worthy and important.

Light and color

In their landscapes and genre scenes, the Impressionist tried to arrest a particular moment in time by pinpointing specific atmospheric conditions—light flickering on water, moving clouds, a burst of rain. Their technique tried to capture what they saw. They painted small commas of pure color one next to another. When viewer stood at a reasonable distance their eyes would see a mix of individual marks; colors that had blended optically. This method created more vibrant colors than colors mixed as physical paint on a palette.

An important aspect of the Impressionist painting was the appearance of quickly shifting light on the surface of forms and the representation changing atmospheric conditions. The Impressionists wanted to create an art that was modern by capturing the rapid pace of contemporary life and the fleeting conditions of light. They painted outdoors (en plein air) to capture the appearance of the light as it flickered and faded while they worked.

Reception

By the 1880s, the Impressionists accepted the name the critics gave them, though their reception in France did not improve quickly. Other artists, such as Mary Cassatt, recognized the value of the Impressionist movement and were invited to join. American and other non-French collectors purchased numerous works by the Impressionists. Today, a large share of Impressionist work remains outside French collections.

What does “Impressionism” mean?

Brushwork, light, and atmosphere

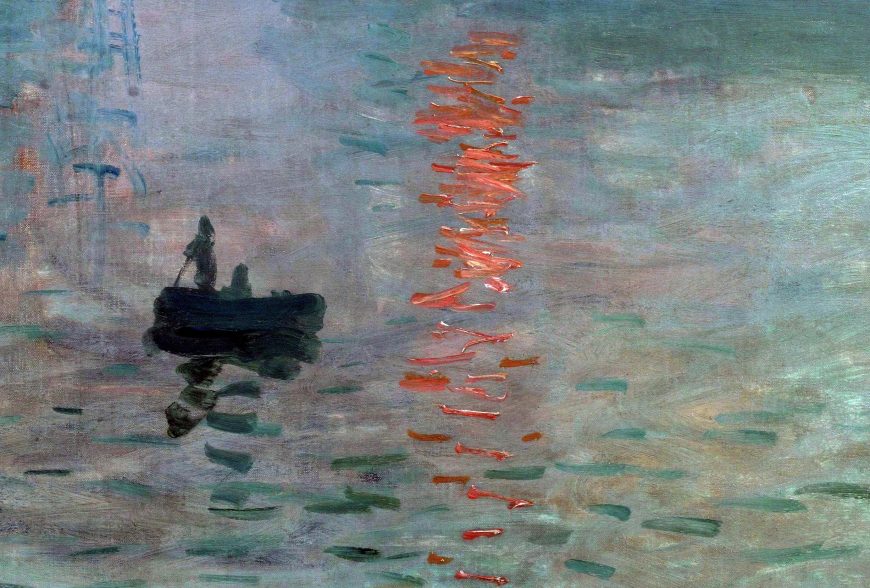

Claude Monet’s Impression: Sunrise is an exemplary Impressionist painting in several ways, not least of which is its title. It depicts a misty harbor scene at Le Havre (a port city in Northern France) in which boats and figures are reduced to flat, shadowy silhouettes, while the red light of the sun reflected on the water takes on tangible form in highly visible brushstrokes.

What we see when we look at the painting is unquestionably painted; Monet made no effort to develop his suggestive image into a more detailed and finished rendering of the scene. The loosely sketched silhouettes of boats exemplify the difficulty of seeing objects in the mist with the sun rising behind them. Monet embraced this difficulty, using it as an occasion to display a painterly rendering that says more about the momentary light and atmospheric conditions than it does about the objects in the scene.

Ask yourself: is there anything in the painting that tells you this is Le Havre? In an interview Monet acknowledged the failure of the painting to depict a recognizable place. When he was asked for the title of the painting for the catalog of what later became known as the first Impressionist exhibition he said: “I couldn’t very well call it a view of Le Havre. So I said: ‘Put Impression.” With this decision Monet unwittingly named an art movement, and this work’s emphasis on brushwork, light, and atmosphere at the expense of the clear representation of objects became a hallmark of the Impressionist style.

Impressionism was not always so well-loved

It may be surprising to know that an art movement so well-loved today—highly successful at auction, the subject of numerous blockbuster exhibits, and a vast number of popular publications—was subjected to a good deal of scorn and ridicule in its early years. Even the term “Impressionism” was first used pejoratively in relation to the new art first exhibited in 1874 by the Société anonyme cooperative d’artistes peintres, sculpteurs, etc. (Anonymous cooperative society of artists, painters, sculptors, etc.). These artists used the term “anonymous” quite intentionally—they wanted to avoid imposing a restrictive label or common agenda on their group, whose members employed a variety of styles and painting techniques. Ultimately, they staged eight exhibitions between 1874 and 1886.

The group included a number of artists who became the most famous Impressionists: Gustave Caillebotte, Mary Cassatt, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot, Camille Pissarro, Pierre Renoir, and Alfred Sisley, as well as many other artists (some of whom are now associated with later modern art movements such as Post-Impressionism or Symbolism). Despite their eclecticism, contemporary viewers and the critics who reviewed the Société anonyme’s exhibitions expected the group to share common goals and characteristics, and the label “Impressionism” soon came to identify a new artistic movement, with some of the artists of the Société anonyme at its core.

A mere impression

The critic Louis Leroy was the first to emphasize the term “impression” in relation to the new painting, adopting it from Monet’s Impression: Sunrise in a satirical dialogue entitled “Exhibition of the Impressionists” that was published in the popular illustrated magazine Le Charivari. Leroy found Monet’s use of “Impression” in his painting’s title particularly appropriate because it suggested that the work was unfinished according to Academic conventions of representation; that is, it represented a mere impression of the scene, rather than a fully structured and completed work of art. Leroy repeatedly emphasized the term “impression” in the dialogue and described many of the paintings by Monet and his fellow exhibitors as sloppy and slapdash, going so far as to compare Monet’s Impression: Sunrise to embryonic wallpaper and Pissarro’s Hoarfrost to paint scraped off of a dirty palette.

Despite this prominent early critical association of the term “impression” with sloppiness, two years later “Impressionism” and “Impressionist” were being widely used to label the new art by its supporters as well as its detractors. It was undoubtedly the flexibility of the term that allowed it to be so widely adopted, but with that flexibility came a certain amount of confusion about the aims of the movement.

Leroy’s usage suggests a hasty and inaccurate “first impression,” but the term also has a very precise and technical connotation as a scientific word designating the stimulation of the optical or other sensory nerves. This scientific definition implies a project of careful observation and objective documentation, but the term is also used for a more subjective and individual response, as when one gives one’s own “impressions” of a person, place, or thing. Hasty generalization or precise observation? Objective documentation or subjective interpretation? All of these contradictory qualities have been associated with the Impressionist movement.

How useful is the term “Impressionism”?

The complex significance of Impressionism expands further when we examine the characteristics emphasized in scholarly and popular writings about the movement. Two quite different artistic projects and sets of characteristics are commonly associated with Impressionism:

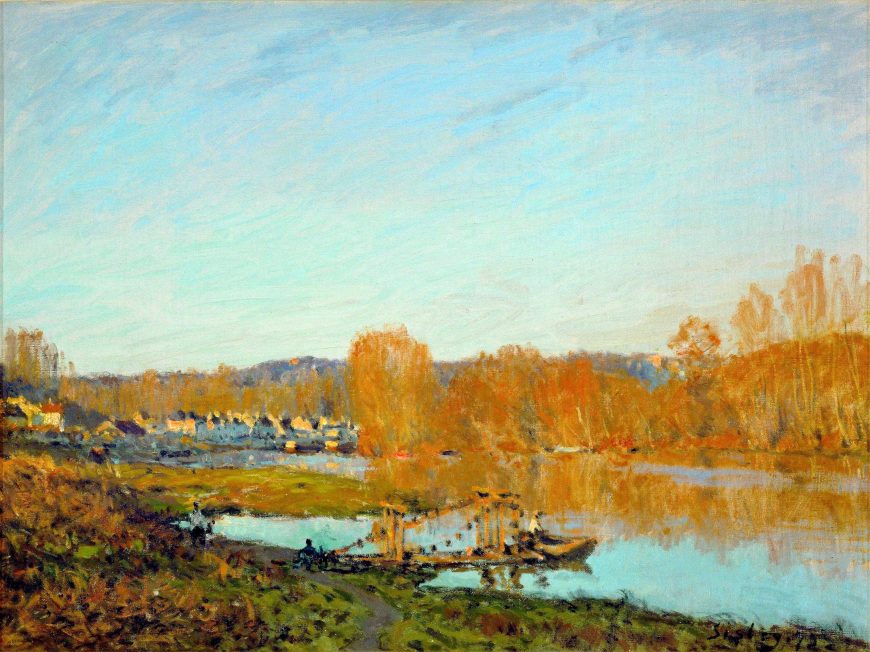

First, a painting is called Impressionist if it exhibits a certain style, consisting of patchy brushwork and a light pastel color scheme that aims to capture transient effects of atmospheric lighting, as can be seen in Sisley’s Autumn: Banks of the Seine near Bougival.

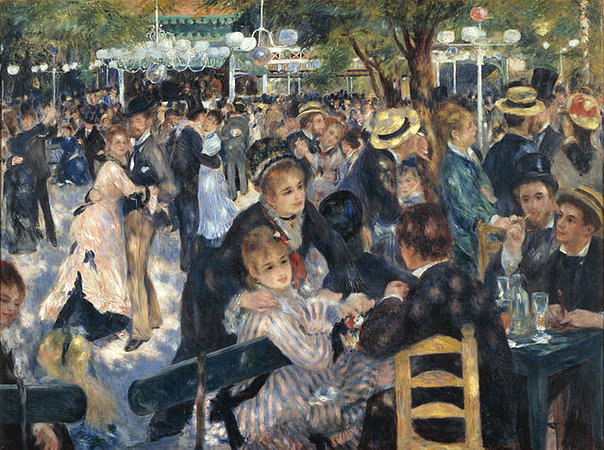

Second, a painting is called Impressionist if it exhibits a certain type of subject matter, typically plein-air (painted out-of-doors) scenes of middle-class men and women at leisure: drinking in cafés, boating, swimming, attending horse races, promenading in gardens, and similar activities.

Berthe Morisot’s painting The Harbor at Lorient, which was shown in the first exhibition of the Société anonyme, exemplifies this second characteristic. We see a very well-dressed bourgeoise woman resting while out for a stroll in the town of Lorient in France. The figure’s white dress and parasol appear somewhat incongruous on the dirty stone wall overlooking a working harbor.

However, not all of the art works shown by members of the Société anonyme exhibit both of these characteristics; in fact, some exhibited neither. The works of Camille Pissarro are typically in the Impressionist style, but as his painting Hoarfrost indicates, he frequently painted the working class at labor rather than the middle classes at leisure. Edgar Degas and Gustave Caillebotte frequently painted the middle classes at leisure, but did not employ the characteristic Impressionist style.

This terminological confusion has led some historians to wish to discard the term Impressionism altogether, but whatever label or labels are attached to them, these two projects—capturing the evanescent effects of atmospheric lighting, and depicting scenes of contemporary middle-class leisure—were significant artistic tendencies in Paris and, slightly later, in the wider Euro-American scene starting in the 1860s and 70s. Rather than attempt to limit the definition of the Impressionist project, we embrace the flexibility of the term.

Impressionism: painting modern life

Aggressively modern

This is one of many paintings by Monet of the railroad bridge leading to Argenteuil, a small town on the outskirts of Paris where the artist lived in the 1870s. The painting demonstrates the Impressionists’ well-known interest in depicting nature and the effects of weather and light, seen here in the expanse of white clouds in blue sky and the reflections in the rippling surface of the river. Highly textured dark green bushes and grass are built up with visible brushstrokes and anchor the painting’s composition on left and right. The subject of the painting, however, is not a timeless rural scene (these were popular with the public — see, for example, this painting by Corot), but an aggressively modern one of a railroad bridge with a train heading over the river.

The bridge was rebuilt at the beginning of the decade after its predecessor was destroyed in the Franco-Prussian war, and its parts were forged at the local ironworks. The steam engine racing across the bridge creates its own billowing gray steam clouds, competing with the natural ones. The sweeping perspective of the bridge suggests the speed and dynamism of modern transportation technology, but Monet also shows that technology as integrally connected to the natural world. The rickety wooden fence in the foreground creates a contrast between old construction materials and the massive concrete and iron pylons supporting the new bridge. Old and new strain to integrate in the modern landscape.

Subjects that matter

Until the last decades of the twentieth century the scholarship on Impressionism paid relatively little attention to the subject matter chosen by the artists. Before then, art historians mostly concentrated on the style of the works and the way Impressionist innovations in form heralded or consolidated what seemed to them to be the most significant feature of modern art: the liberation of the artist from the constraints of convention, and the “evolution” of art toward flatness and abstraction. In recent decades, however, art historians have seriously considered the subject matter represented in Impressionist paintings and how this subject matter would have been understood by contemporary viewers.

Painting modern life

The Impressionist style can, of course, be applied to any subject matter, but Impressionist artists concentrated on a surprisingly limited range of subjects: typically, middle-class leisure in modern urban or suburban environments such as the Paris boulevard depicted in Monet’s Boulevard des Capucines or Railroad Bridge at Argenteuil. In one sense, the Impressionists continued the tradition of earlier nineteenth-century Realists like Jean-François Millet (for example in his painting L’Angélus) in their insistence on painting scenes from contemporary life. They rejected historical, mythological, and other exotic subjects and took as their dictum, “Il faut être de son temps,” “one must be of one’s own time.”

However, for the Impressionists, unlike the Realists, contemporary subjects typically did not mean rural or provincial scenes, which often suggested timeless forms of life and labor (as in Millet’s L’Angélus), but rather urban and suburban subjects that were changing rapidly. In this they are among the first artists to examine an important change in human geography that had significantly transformed the human experience: the shift of populations from primarily rural to urban areas that accompanied the Industrial Revolution and its large-scale economic shift from agricultural to industrial production.

In 1863, the poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire wrote an influential essay titled “The Painter of Modern Life” that called for an artist who would stroll through the new spaces of the city, keenly observing the actions of its inhabitants and viewing the streets and crowds as though they constituted a sort of improvised theater put on for his observation. Monet’s Boulevard des Capucines presents a characteristically modern scene of the broad, tree-lined boulevards that were cut across the older, less regular streets and alleys of Paris, offering a sweeping perspective that was not previously available in the city.

Although they did not insist upon technological subjects as much as later modern art movements such as Italian Futurism or American Precisionism did, the Impressionists had a recognizable predilection for painting the spaces of Paris as it had been transformed within the past few decades. Along with the more stereotypical plein-air garden and landscape subjects, the Impressionists also frequently turned to scenes of contemporary urban experience. They painted Parisian cafés and beer halls; they painted the large theaters, opera houses, and cabarets of the city’s night-life, illuminated by the eerie green glow of the new gas lighting; they painted the bridges and grand boulevards of modern urban planning; they painted the new train stations, glass-and-iron cathedrals to modern technology and its promise of rapid movement of goods and ease of travel; and they painted the suburban restaurants, racetracks, beach resorts, and parks where the rising middle classes spent their leisure hours. These subjects may appear charmingly quaint to our eyes, but at the time they were as aggressively contemporary as paintings of skyscrapers, airports, highway rest areas, and office parks would be today.

Middle-class leisure

Also unlike the Realists, the Impressionists tended to paint middle class leisure rather than lower class labor. This is a somewhat surprising limitation. Living alongside affluent urban professionals and moving through the same streets were thousands of poor manual laborers. But when we examine a panoramic street scene such as Gustave Caillebotte’s Paris Street; Rainy Day—another view of a modern boulevard—it is surprising to note there is only one person on the street whose dress marks him as lower class and whose occupation signals active labor: a distant man carrying a ladder, easily overlooked just to the right of the foreground man’s head. The exceptions to this general rule that the Impressionists painted bourgeois leisure rather than lower-class labor actually help to prove the rule. Impressionist paintings that show lower-class labor tend to depict the support industries of middle-class leisure: café waiters, beer-hall waitresses, cabaret singers, ballet dancers, laundresses, milliners, and prostitutes (and not the labor necessary to maintain the infrastructure of the city and the basic needs of its inhabitants). Even the paintings of lower class labor are fundamentally about middle class leisure.

Haussmann: the Demolisher and the creation of modern Paris

Paris: Narrow streets and barricades

During each of the previous political revolts (1789, 1830, 1848, and again in 1871), sections of Paris had succumbed to the revolutionaries. These successes were due in part to the political sympathies of the citizens of Paris, but the crooked narrow lanes of the medieval city also played a role. During times of conflict, urban mobs would blockade the maze that was the streets of Paris. Such barricades (makeshift barriers erected across streets to prevent the movement of opposing forces) proved very effective and made Paris all but uncontrollable at times. Think back to Eugène Delacroix’s painting of the revolution of 1830, Liberty Leading the People—Marianne (Liberty) is shown rising over a barricade of just this sort.

Napoleon III and the Second Empire

During the period known as the Second Empire (1852-70), Napoleon III, the great-nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte (emperor of France in the early nineteenth century), ruled France. He asked an administrator, Baron Georges-Eugene Haussmann, to modernize Paris—to bring clean water and modern sewers to the fast growing city, to light the streets with gas lanterns, to construct a central market (Les Halles), and to build parks, schools, hospitals, asylums, prisons, and administrative buildings. But the most ambitious aspect of Haussmann’s plan was to literally reshape the city.

Haussmann’s reconstruction of Paris

For his role in changing the Paris cityscape, Haussmann would acquire the nickname “the demolisher.” He plowed over the ancient, winding streets of the city (the same narrow streets that had proved so useful to revolutionaries). In their place, he created broad straight boulevards that were impervious to the barricade—and, equally important, they could better accommodate the free movement of troops.

The avenues also allowed for the easy flow of commerce and so were a boon for business. Napoleon III had dreamed of a new imperial city whose very streets spoke of the glory of the French empire. Haussmann delivered.

As with nearly every urban renovation, a percentage of the population was displaced. Haussmann forced citizens from their homes as these buildings were torn down to make way for the clean lines of the new city. The wealthy were quickly accommodated. The new boulevards were lined with fashionable apartment houses. It was, as usual, the poor that really suffered.

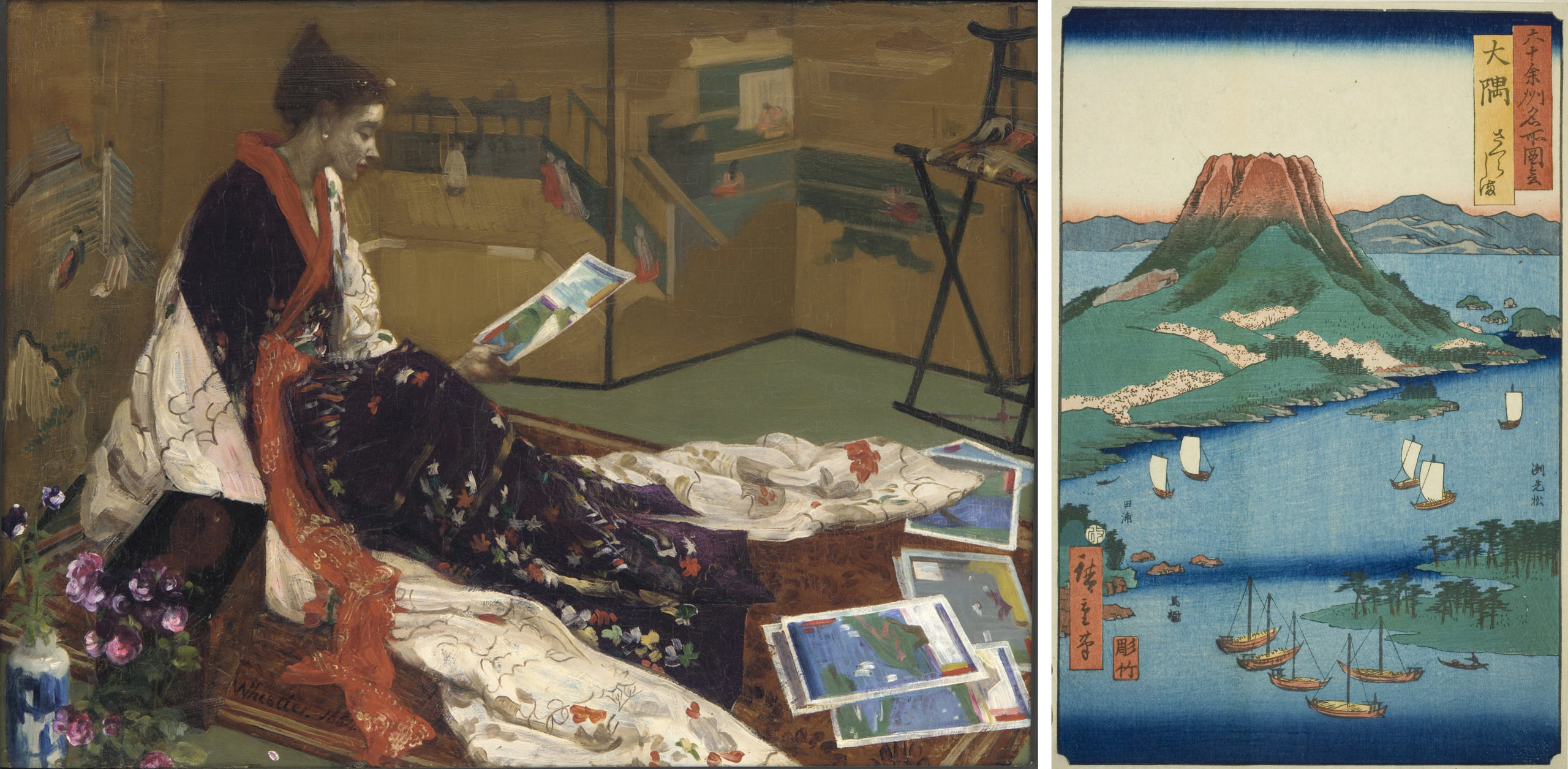

Japonisme

James McNeill Whistler’s Caprice in Purple and Gold is an early example of Japonisme, a term coined by the French art critic Philippe Burty in 1872. It refers to the fashion for Japanese art in the West and the Japanese influence on Western art and design following the opening of formerly isolated Japan to world trade in 1853. In Whistler’s painting, a European woman sits on the floor wearing richly embroidered silks like those of a Japanese courtesan while she studies a set of woodblock prints by the Japanese artist Hiroshige. Decorative objects from both Japan and China surround her, including a large gold Japanese folding screen.

A decorative art fashion

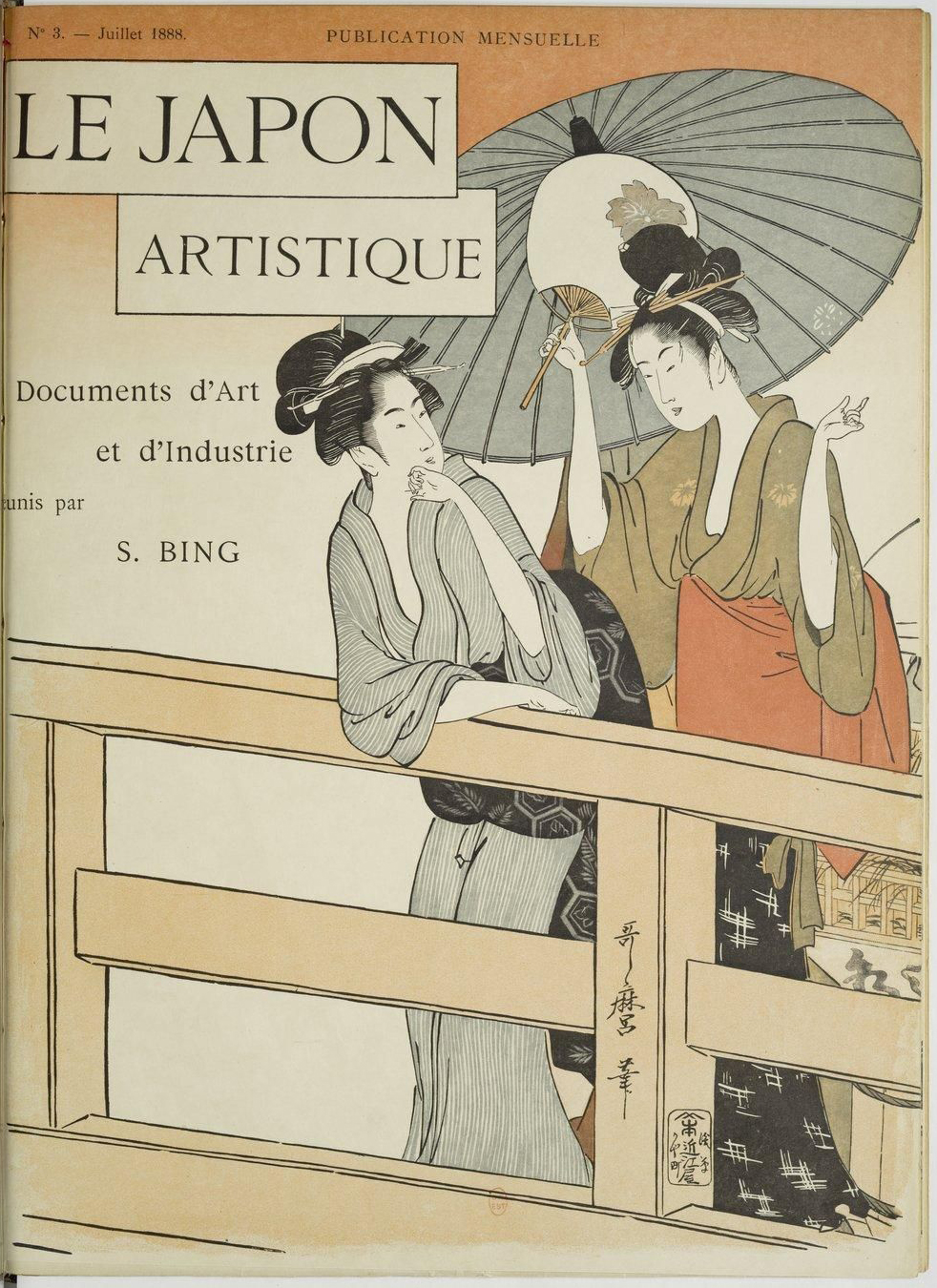

The late-nineteenth century Western fascination with Japanese art directly followed earlier European fashions for Chinese and Middle Eastern decorative arts, known respectively as Chinoiserie and Turquerie. The art dealer Siegfried Bing was one of the earliest importers of Japanese decorative arts in Paris. He sold them in his shop La Porte Chinoise, as well as promoting them in his lavish magazine Le Japon Artistique, published from 1888-1891. Bing was also a major supporter of Art Nouveau, a fin-de-siècle decorative style greatly influenced by Japonisme.

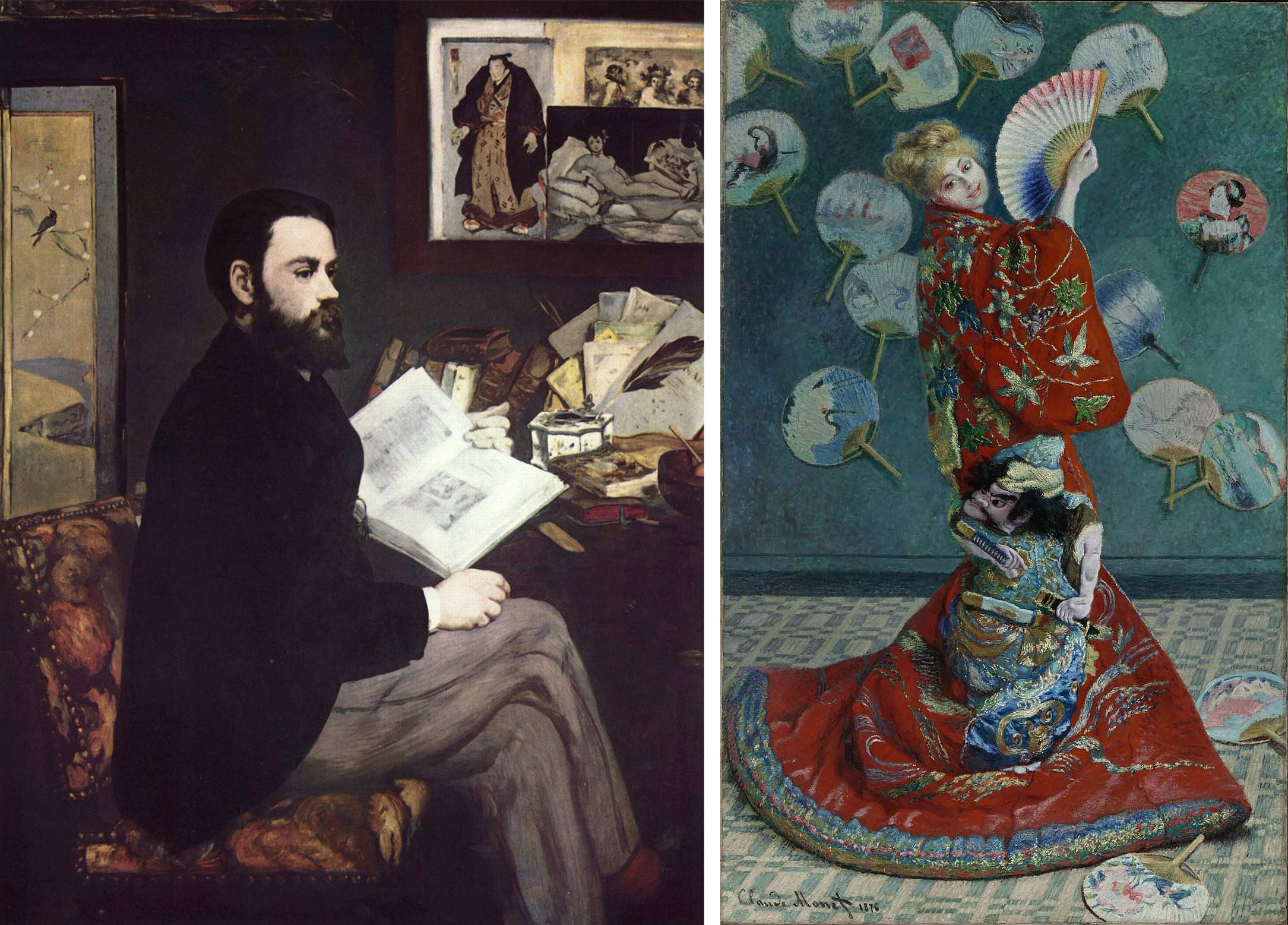

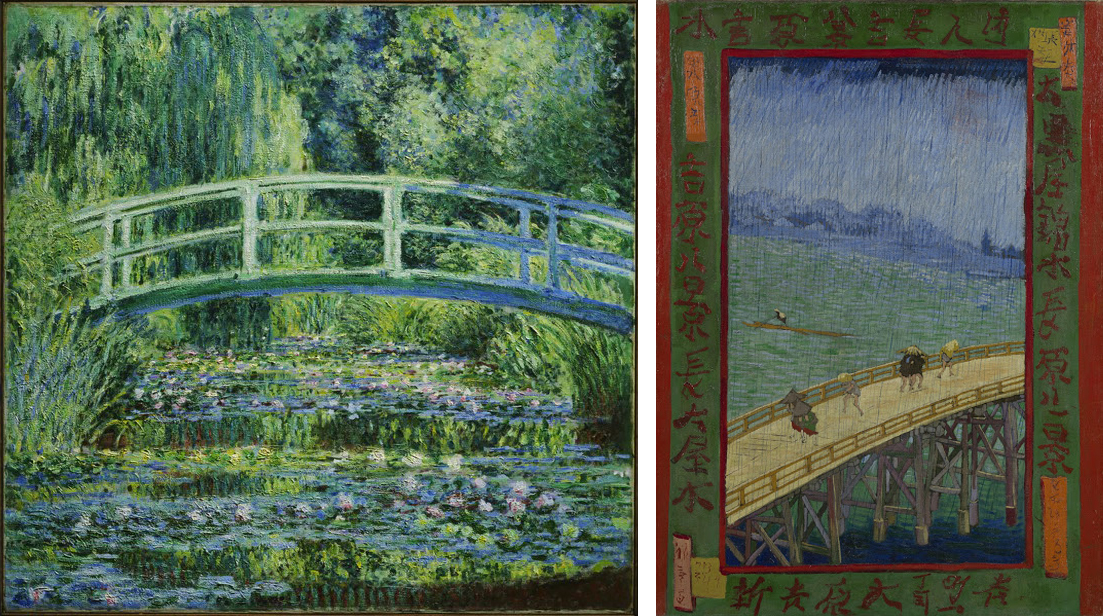

Works by prominent artists associated with Impressionism and Post-Impressionism bear witness to the late 19th-century fashion for Japanese art and decorative objects. In Manet’s portrait of Emile Zola the novelist and art critic sits at his overflowing desk. Immediately noticeable among the artworks surrounding him are a Japanese woodblock print of a wrestler and a Japanese gold screen. Monet portrayed his wife Camille dressed in a Japanese kimono surrounded by Japanese fans, and his water garden at Giverny was inspired by Japanese gardens depicted in prints and included a Japanese-style wooden bridge. In addition to painting copies of several Japanese woodblock prints, such as Bridge in the Rain (After Hiroshige), Vincent van Gogh depicted them in the background of several portraits.

A source for modern artists

Japonisme coincided with modern art’s radical upending of the Western artistic tradition and had significant effects on Western painting and printmaking. In this regard, Japanese art affected modern art in much the same way that encounters with African and Oceanic art and artifacts did a few decades later. Many late-19th century modern artists not only admired and collected Japanese prints, they derived and adopted both compositional and stylistic approaches from them.

Japanese woodblock prints called ukiyo-e, or “pictures of the floating world,” were a cheap popular art form in Japan during the Edo Period (1615-1868). They were associated with urban entertainment districts (the so-called floating world) in Japan and typically portrayed famous actors, courtesans, and wrestlers, as well as landscape views of well-known sites. Ukiyo-e prints first appeared in Europe as packaging material used to protect valuable imported porcelain objects, but they attracted the interest of European artists and art collectors and were soon imported for their own sake.

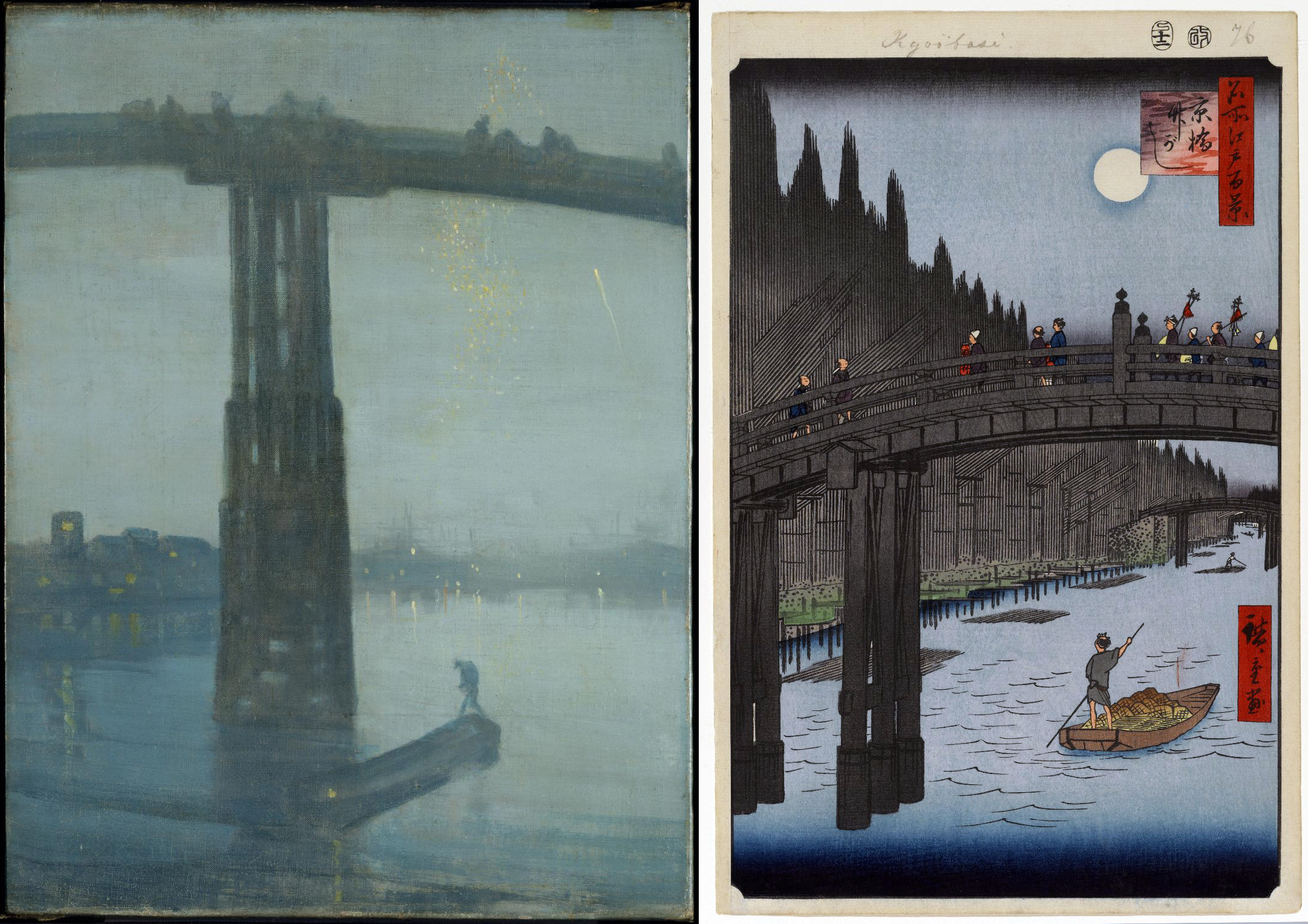

In addition to depicting Japanese decorative objects, Whistler used both subjects and compositional strategies derived from Hiroshige’s prints of notable views in Japan. One of his most innovative and well-known paintings, Nocturne in Blue and Gold: Battersea Bridge, echoes Hiroshige’s Kyobashi Bridge in both its nighttime subject and the abruptly cropped view of the bridge in the foreground. The large areas of flat colors typical of Japanese woodblock prints may also have influenced Whistler’s simplified forms and reduced color range.

Impressionism

The Impressionists were also interested in Japanese prints. After visiting an 1890 exhibition of ukiyo-e prints in Paris, Mary Cassatt employed similar decorative patterns, flattened spaces and simplified figures in a series of color etchings that includes The Letter. Cassatt’s favored subjects, women in domestic interiors playing with children or grooming themselves, were common in ukiyo-e prints, a fact that undoubtedly contributed to her interest in them.

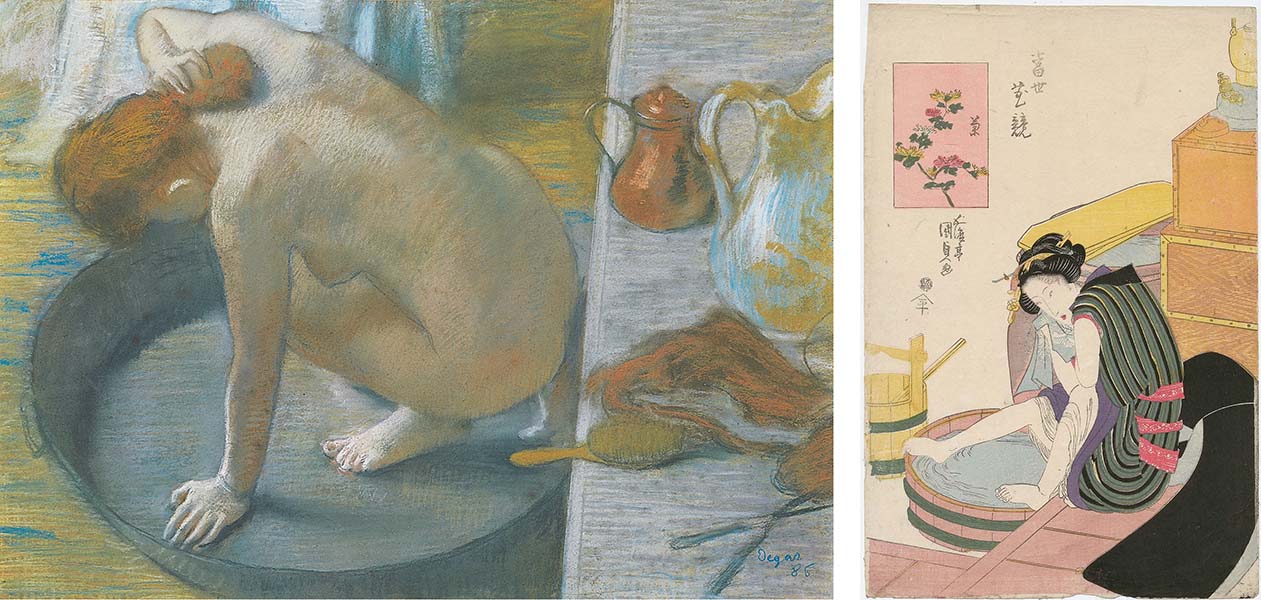

Cassatt’s friend Edgar Degas used Japanese compositional devices to depict women bathing. In The Tub, a woman sponging her neck is shown from an elevated vantage point that emphasizes the flat shapes and patterns created by her body and the surrounding objects. The curve of the tub is continued in the woman’s back, while the vertical of her left arm parallels the edge of the shelf on the right side of the painting. Thus, although Degas uses traditional chiaroscuro shading to define three-dimensional forms, abstract pattern and surface design dominate the image, flattening the space and rendering it ambiguous.

Like Degas’ The Tub, Kunisada’s Chrysanthemum shows a bathing woman surrounded by ordinary household objects — note the water heater and scrub brush in the upper right corner. Although the viewing angle is not as high as that in Degas’ work, we see the woman from above, and Kunisada uses the space and objects surrounding her to construct a visual frame for the figure rather than clearly defining an interior space. The repetition of colors and simplified shapes creates a strong surface pattern, as does the lack of chiaroscuro shading.

We’ll look at the influences of Japonisme on Post-Impressionists in the next chapter!

a panel of judges determining which artists may enter an exhibition

artwork whose subject matter focuses on scenes from the real or mythological past, often with a moral message and dramatic staging

art focusing on natural scenes, sometimes with human-made structures and/or people, but focusing on the environment itself

scenes of everyday life

a surface for mixing pigments—of the selection of colors an artist uses in an artwork

artwork (usually paintings or drawings of outside views) made while out of doors

skilled application of paint, focusing on texture over line and often reflecting visible brushtrokes

the organization of elements within a work of art

a system for depicting space that is based on the optical illusion that parallel lines seem to converge as they recede into the distance

depiction tending toward flattened shapes rather than three-dimensional forms, sometimes to the point of non-representation (pure abstraction)

the fashion for Japanese art in the West and the Japanese influence on Western art and design following the opening of formerly isolated Japan to world trade in 1853

a relief print made from one of more carved and inked wooden blocks

"pictures of the floating world"; inexpensive woodcut prints from Edo Period Japan featuring urban entertainment

from the Latin chiaro (light) + scuro (dark), the artistic technique of combining light and shadow to create the illusion of three-dimensional form