10

Dr. Beth Harris; Dr. Steven Zucker; Dr. Charles Cramer; Dr. Kim Grant; and Lynn Robinson

In this chapter

Pablo Picasso, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon

Cézanne’s ghost, Matisse’s Bonheur de Vivre, and Picasso’s ego

One of the most important canvases of the twentieth century, Picasso’s great breakthrough painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon was constructed in response to several significant sources.

First amongst these was his confrontation with Cézanne’s great achievement at the posthumous retrospective mounted in Paris a year after the artist’s death in 1907.

The retrospective exhibition forced the young Picasso, Matisse, and many other artists to contend with the implications of Cézanne’s art. Matisse’s Bonheur de Vivre of 1906 [see previous chapter] was one of the first of many attempts to do so, and the newly completed work was quickly purchased by Leo & Gertrude Stein and hung in their living room so that all of their circle of avant-garde writers and artists could see and praise it. And praise it they did. Here was the promise of Cézanne fulfilled—and one which incorporated lessons learned from Seurat and van Gogh, no less! This was just too much for the young Spaniard.

Pablo becomes Picasso

By all accounts, Picasso’s intensely competitive nature literally forced him to out do his great rival. Les Demoiselles D’Avignon is the result of this effort. Let’s compare canvases. Matisse’s landscape is a broad open field with a deep recessionary vista. The figures are uncrowded. They describe flowing arabesques that in turn relate to the forms of nature that surround them. Here is languid sensuality set in the mythic past of Greece’s golden age.

In very sharp contrast, Picasso, intent of making a name for himself (rather like the young Manet and David), has radically compressed the space of his canvas and replaced sensual eroticism with a kind of aggressively crude pornography. (Note, for example, the squatting figure at the lower right.) His space is interior, closed, and almost claustrophobic. Like Matisse’s later Blue Nude (itself a response to Les Demoiselles d’Avignon), the women fill the entire space and seem trapped within it. No longer set in a classical past, Picasso’s image is clearly of our time. Here are five prostitutes from an actual brothel, located on a street named Avignon in the red-light district in Barcelona, the capital of Catalonia in northern Spain—a street, by the way, which Picasso had frequented.

Picasso has also dispensed with Matisse’s clear, bright pigments. Instead, the artist chooses deeper tones befitting urban interior light. Gone too, is the sensuality that Matisse created. Picasso has replaced the graceful curves of Bonheur de Vivre with sharp, jagged, almost shattered forms. The bodies of Picasso’s women look dangerous as if they were formed of shards of broken glass. Matisse’s pleasure becomes Picasso’s apprehension. But while Picasso clearly aims to “out do” Matisse, to take over as the most radical artist in Paris, he also acknowledges his debts. Compare the woman standing in the center of Picasso’s composition to the woman who stands with elbows raised at the extreme left of Matisse’s canvas: like a scholar citing a borrowed quotation, Picasso footnotes.

The creative vacuum-cleaner

Picasso draws on many other sources to construct Les Demoiselles D’Avignon. In fact, a number of artists stopped inviting him to their studio because he would so freely and successfully incorporate their ideas into his own work, often more successfully than the original artist. Indeed, Picasso has been likened to a “creative vacuum cleaner,” sucking up every new idea that he came across. While that analogy might be a little coarse, it is fair to say that he had an enormous creative appetite. One of several historical sources that Picasso pillaged is archaic art, demonstrated very clearly by the left-most figure of the painting, who stands stiffly on legs that look awkwardly locked at the knee. Her right arm juts down while her left arm seems dislocated (this arm is actually a vestige of a male figure that Picasso eventually removed). Her head is shown in perfect profile with large almond shaped eyes and a flat abstracted face. She almost looks Egyptian. In fact, Picasso has recently seen an exhibition of archaic (an ancient pre-classical style) Iberian (from Iberia–the land mass that makes up Spain and Portugal) sculpture at the Louvre. Instead of going back to the sensual myths of ancient Greece, Picasso is drawing on the real thing and doing so directly. By the way, Picasso purchased, from Apollinaire’s secretary, two archaic Iberian heads that she had stolen from the Louvre! Some have suggested that they were taken at Picasso’s request. Years later Picasso would anonymously return them.

Spontaneity, carefully choreographed

Because the canvas is roughly handled, it is often thought to be a spontaneous creation, conceived directly. This is not the case. It was preceded by nearly one hundred sketches. These studies depict different configurations. In some there are two men in addition to the women. One is a sailor. He sits in uniform in the center of the composition before a small table laden with fruit, a traditional symbol of sexuality. Another man originally entered from the left. He wore a brown suit and carried a textbook, he was meant to be a medical student.

The (male) artist’s gaze

Each of these male figures was meant to symbolize an aspect of Picasso. Or, more exactly, how Picasso viewed these women. The sailor is easy to figure out. The fictive sailor has been at sea for months, he is an obvious reference to pure sexual desire. The medical student is trickier. He is not there to look after the women’s health but he does see them with different eyes. While the sailor represents pure lust, the student sees the women from a more analytic perspective. He understands how their bodies are constructed, etc. Could it be that Picasso was expressing the ways that he saw these women? As objects of desire, yes, but also, with a knowledge of anatomy probably superior to many doctors. What is important is that Picasso decides to remove the men. Why? Well, to begin, we might imagine where the women focused their attention in the original composition. If men are present, the prostitutes attend to them. By removing these men, the image is no longer self-contained. The women now peer outward, beyond the confines of the picture plane that ordinarily protect the viewer’s anonymity. If the women peer at us, like in Manet’s Olympia of 1863, we, as viewers, have become the customers. But this is the twentieth century, not the nineteenth and Picasso is attempting a vulgar directness that would make even Manet cringe.

Picasso’s perception of space

So far, we have examined the middle figure which relates to Matisse’s canvas; the two masked figures on the right side who refer, by their aggression, to Picasso’s fear of disease; and, we have linked the left-most figure to archaic Iberian sculpture and Picasso’s attempt to elicit a sort of crude primitive directness. That leaves only one woman unaccounted for. This is the woman with her right elbow raised and her left hand on a sheet pulled across her left thigh. The table with fruit that had originally been placed at the groin of the sailor is no longer round, it has lengthened, sharpened, and has been lowered to the edge of the canvas. This table/phallus points to this last woman. Picasso’s meaning is clear, the still life of fruit on a table, this ancient symbol of sexuality, is the viewer’s erect penis and it points to the woman of our choice. Picasso was no feminist. In his vision, the viewer is male.

Although explicit, this imagery only points to the key issue. The woman that has been chosen is handled distinctly in terms of her relation to the surrounding space. Yes, more about space. Throughout the canvas, the women and the drapery (made of both curtains and sheets) are fractured and splintered. Here is Picasso’s response to Cezanne and Matisse. The women are neither before nor behind. As in Matisse’s Red Studio, which will be painted four years later, Picasso has begun to try to dissolve the figure/ground relationship. Now look at the woman that Picasso tells us we have chosen. Her legs are crossed and her hand rests behind her head, but although she seems to stand among the others, her position is really that of a figure that lies on her back. The problem is, we see her body perpendicular to our line of sight. Like Matisse and Cezanne before him, Picasso here renders two moments in time: as you may have figured out, we first look across at the row of women, and then we look down on to the prostitute of our/Picasso’s choice.

African masks, women colonized

The two figures at the right are the most aggressively abstracted with faces rendered as if they wear African masks. By 1907, when this painting was produced, Picasso had begun to collect such work. Even the striations that represent scarification is evident. Matisse and Derain had a longer standing interest in such art, but Picasso said that it was only after wandering into the Palais du Trocadero, Paris’s ethnographic museum, that he understood the value of such art. Remember, France was a major colonial power in Africa in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Much African art was ripped from its original geographic and artistic context and sold in Paris. Although Picasso would eventually become more sophisticated regarding the original uses and meaning of the non-Western art that he collected, in 1907 his interest was largely based on what he perceived as its alien and aggressive qualities.

William Rubin, once the senior curator of the department of painting and sculpture at The Museum of Modern Art, and a leading Picasso scholar, has written extensively about this painting. He has suggested that while the painting is clearly about desire (Picasso’s own), it is also an expression of his fear. We have already established that Picasso frequented brothels at this time so his desire isn’t in question, but Rubin makes the case that this is only half the story. Les Demoiselles D’Avignon is also about Picasso’s intense fear…his dread of these women or more to the point, the disease that he feared they would transmit to him. In the era before antibiotics, contracting syphilis was a well founded fear. Of course, the plight of the women seems not to enter Picasso’s story.

Picasso’s Early Work

Age twenty and looking rather goth

When I’m in the galleries at The Museum of Modern Art in New York, I obviously spend a good deal of time looking at the art. But I also watch people look at the art and listen to what they have to say. The comments that people make can be quite thoughtful and visitor comments and questions have added enormously to my appreciation of the art over the years. Still, there are many comments that are born of pure befuddlement. And many of these target Picasso.

Many people seem to believe that Picasso’s abstraction of the human figure, his penchant for reconfiguring the body by mis-aligning a nose or an eye, for instance, is the result of his inability to draw. Nothing could be farther from the truth. There is an old anecdote that tells of Picasso, who, upon emerging from an exhibition of drawings by young children, says, “When I was their age I could draw like Raphael, but it took me a lifetime to learn to draw like them.”

Perhaps this quote is apocryphal, but it points to something undeniably true: Picasso was an extraordinary craftsman, even when measured against the old masters. That he chose to struggle to overcome his visual heritage in order to find a language more responsive to the modern world is an important triumph that has had a vast effect upon our world. Picasso’s art has transformed and inspired not only artists, but also architects, designers, writers, mathematicians, and even philosophers. We may look at Picasso’s art in museums, but his art—via these translators—has therefore had a profound influence on what we see in our everyday life. Just think of the advertisements for products we buy, buildings in which we live and work, books we read, and even the way we conceive of reality.

“My kid could make that”

There is no question that Picasso’s art has had a most profound impact on the twentieth century. While Picasso suggests the value of unlearning the academic tradition, it is important to remember that he had mastered its techniques by a very early age. His father, Don José Ruiz Blasco, was a drawing teacher and curator at a small museum. The young Picasso began drawing and painting by age seven or eight. By age ten, Picasso assisted his father, sometimes painting the minor elements of the elder’s canvases. Soon after his father became a professor at the art academy in Barcelona, the young Picasso completed the entrance examinations (in record time) and was advanced to the school’s upper-level program. He repeated this feat when he applied to the Royal Academy in Madrid.

Picasso in Paris

Like Van Gogh had done before him, Picasso arrived in Paris determined to work through the avant-garde’s techniques and subjects to better understand such art. An example of his explorations of the achievements of contemporary art in Paris can be seen by comparing a painting by Degas to one by Picasso.

It is not surprising that Picasso, the great draftsman, would be interested in the work of the “odd man out” Degas, who nearly alone among the Impressionists retained the primacy of line. In the example Woman Ironing, Picasso has infused a somewhat maudlin weariness to his attenuated and curiously sensual laborer. Still, Picasso understands Degas’s experimentation with abstraction. Note how in Degas’s image, the luminous negative space defined between the arms refuses to recede beyond the figure, remaining trapped instead. Likewise, Picasso defines and centers an almost identical form. Notice, too, the bowl that Picasso places in the lower right corner. Like everything in this canvas, it is roughly formed with a dry brush. Still, the simple strokes of white and dark gray that define the volume speak to the magical pleasure of rendering space, a love that Picasso carries with him through out his career.

Family of Saltimbanques

This great, early painting by Picasso portrays a family of saltimbanques. These are wandering circus performers that move from town to town—never truly welcome, and only briefly tolerated for their ability to entertain.

Like so many of Picasso’s early subjects during his so-called Blue and Rose periods in the first years of the twentieth century, here is a group of disenfranchised, alienated people that live on the fringes of society. This particular group includes characters from the sixteenth-century Italian performing tradition of commedia dell’arte. One such figure is the rogue wit known as the Harlequin, who wears a suit of multicolored triangles. Picasso seems to have identified with such characters at this time. As he often reminded people, he was very poor at this point in his career. A Spaniard in France who did not yet speak the language, and still an unknown artist only in his mid-twenties, Picasso might well have felt an affinity with itinerant outsiders such as the saltimbanques.

The Laundry Barge

In Paris in 1904, Picasso rented a studio in an old, dilapidated building filled with artists and poets. Located at 13 Rue Ravignan, the building was dubbed the Bateau-Lavoir (or laundry barge) by poet-in-residence, Max Jacob. It is at this time that Picasso first came into contact with French painter Henri Matisse, as well as American ex-pat Gertrude Stein, who—along with her brother Leo—was one of the foremost patrons of modern art in Paris.

Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Gertrude Stein

The Laundry Barge

In 1904, Picasso rented a studio in an old, dilapidated building in Paris filled with artists and poets. Located at 13 Rue Ravignan, the building was dubbed the Bateau-Lavoir (or laundry barge) by poet-in-residence, Max Jacob.

It was at this time that Picasso first came into contact with French painter Henri Matisse, as well as the American expatriate Gertrude Stein. Gertrude commissioned a portrait by Picasso in 1905, around the same time that her brother Leo bought Matisse’s Bonheur de Vivre. As the strong solid woman of Picasso’s painting suggests, Gertrude Stein was a formidable presence in Paris of the early 20th century. An influential writer, she, along with her brother, was an important patron of the arts, known for hosting salons that brought together some of the period’s most famous artists, writers, and intellectuals.

Gertrude and Picasso

At the time of his commission, Picasso hoped to cultivate a relationship with the wealthy Stein, who had already been impressed by the innovative style of Matisse [see previous chapter].

In contrast to Matisse’s bright colors and sensuous undertones in paintings like Bonheur de Vivre, Picasso’s portrait demonstrates the angular distortions and formal experimentation that would characterize his artwork through the invention of Cubism.

The story goes that Stein sat for Picasso so many times (as many as 90 sittings) that eventually he said he could no longer see her when he looked at her. He then wiped out her face in the painting and left on a trip to Spain. When he returned to Paris in the fall, Picasso quickly completed the portrait—supposedly from memory—in a way that challenged traditional expectations of portraiture. According most portraits tell us about the sitter through their physical likeness and expressive detail, Picasso instead showed his subject as a massive hulking figure who stares blankly past the viewer.

Painted in dull, muted colors, Stein’s broad body fills Picasso’s canvas. Her bulky form sits on a large armchair or sofa and stiffly leans forward, imposing in the way she rests her arms and large hands heavily on the folds of her skirt. In contrast to the rounded mass of the figure, Stein’s face has a planar quality that seems hard and mask-like—an effect heightened by the geometric treatment of the eyes, nose, and mouth, and the dark modeling that distinguishes its angular contours from the rest of her head and body.

Picasso’s odd rendering of Stein’s features reflects the influence of African and Iberian art on the artist, but it might also allude to art’s inability to reveal the truth about an individual. Like many European artists at the time, Picasso looked to ancient and non-western art as a source of primitive inspiration—a colonialist notion that viewed “uncivilized” cultures to be more spiritually authentic than the sophisticated cities of Europe. Thus, while Picasso admired the formal qualities of these sculptural influences, he also believed them better able to communicate deeper meaning and ideas that could not be conveyed through the established traditions of Western art.

The Power of the Artist

By reworking Gertrude Stein’s portrait in a primitive style, Picasso claimed for himself the power to represent the woman as she really is, not merely as a likeness of her physical appearance. Stein’s response to the image supports this point of view. In her book on Picasso, she wrote:

I was and I still am satisfied with my portrait, for me, it is I, and it is the only reproduction of me which is always I, for me.[1]

Like Picasso’s reliance on the expressive potential of primitive forms, Stein’s repetitive word play demonstrates her own interest in how language could convey meaning through formal effect instead of descriptive content. For the artist and the author, both challenged the conventions of their media in order to explore the power of art to communicate in new ways that would be appropriate to the modern era.

Inventing Cubism

During the summer of 1908, Braque returned to Cézanne’s old haunt for a second summer in a row. Previously he had painted this small port just south of Aix-en-Provence with the brilliant irreverent colors of a Fauve (Braque along with Matisse, Derain, and others defined this style from about 1904 to 1907). But now, after Cézanne’s death and after having met Picasso, Braque set out on a very different tack, the invention of Cubism.

Cubism is a terrible name. Except for a very brief moment, the style has nothing to do with cubes. Instead, it is an extension of the formal ideas developed by Cézanne and broader perceptual ideas that became increasingly important in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These were the ideas that inspired Matisse as early as 1904 and Picasso perhaps a year or two later. We certainly saw such issues asserted in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. But Picasso’s great 1907 canvas is not yet Cubism. It is more accurate to say that it is the foundation upon which Cubism is constructed. If we want to really see the origin of the style, we need to look beyond Picasso to his new friend Georges Braque.

A New Perspective

The young French Fauvist, Georges Braque, had been struck by both the posthumous Cézanne retrospective exhibition held in Paris in 1907 and his first sight of Picasso’s radical new canvas, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Like so many people that saw it, Braque is reported to have hated it—Matisse, for example, predicted that Picasso would be found hanged behind the work, so great was his mistake. Nevertheless, Braque stated that it haunted him through the winter of 1908. Like every good Parisian, Braque fled Paris in the summer and decided to return to the part of Provence in which Cézanne had lived and worked. Braque spent the summer of 1908 shedding the colors of Fauvism and exploring the structural issues that had consumed Cézanne and now Picasso. He wrote:

It [Cézanne’s impact] was more than an influence, it was an invitation. Cézanne was the first to have broken away from erudite, mechanized perspective…[2]

Like Cézanne, Braque sought to undermine the illusion of depth by forcing the viewer to recognize the canvas not as a window but as it truly is, a vertical curtain that hangs before us. In canvases such as Houses at L’Estaque ( 1908), Braque simplifies the form of the houses (here are the so called cubes), but he nullifies the obvious recessionary overlapping with the trees that force forward even the most distant building.

Brothers of Invention

When Braque returned to Paris in late August, he found Picasso an eager audience. Almost immediately, Picasso began to exploit Braque’s investigations. But far from being the end of their working relationship, this exchange becomes the first in a series of collaborations that lasts six years and creates an intimate creative bound between these two artists that is unique in the history of art.

Between the years 1908 and the beginning of the First World War in 1914, Braque and Picasso work together so closely that even experts can have difficulty telling the work of one artist from the other. For months on end they would visit each others studio on an almost daily basis sharing ideas and challenging each other as they went. Still, a pattern did emerge and it tended to be to Picasso’s benefit. When a radical new idea was introduced, more than likely, it was Braque that recognized its value. But it was inevitably Picasso who realized its potential and was able to fully exploit it.

Tough Art

By 1910, Cubism had matured into a complex system that is seemingly so esoteric that it appears to have rejected all esthetic concerns. The average museum visitor, when confronted by a 1910 or 1911 canvas by Braque or Picasso, the period known as Analytic Cubism, often looks somewhat put upon even while they may acknowledge the importance of such work. I suspect that the difficulty, is, well…, the difficulty of the work. Cubism is an analysis of vision and of its representation and it is challenging. As a society we seem to believe that all art ought to be easily understandable or at least beautiful. That’s the part I find confusing.

Cubism and multiple perspectives

by DR. CHARLES CRAMER and DR. KIM GRANT

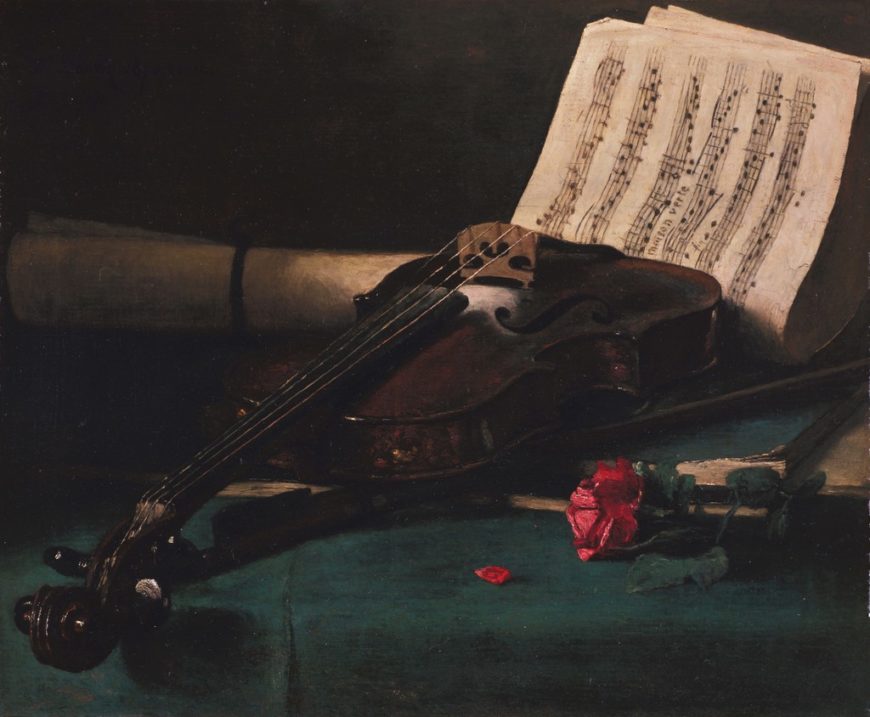

At first sight the objects in Georges Braque’s Pitcher and Violin appear arbitrarily distorted, but they are not. One tactic that Braque uses here is depicting objects from multiple perspectives. While most of Braque’s violin is depicted frontally, like an illustration in an encyclopedia, the scroll at the top of the neck is represented from the side, and the bridge that holds the strings over the neck and sound board has been flipped up.

The pitcher is also depicted mostly from the side, but we see the top rim from above on the left-hand side, while the spout is depicted from a slightly less elevated angle. Similarly, while Braque appears to have depicted the violin standing improbably on its bottom edge, it is more likely that we are expected to understand it as lying flat on a table. Thus, we are looking down on the violin at the same time as we look straight ahead at the body of the pitcher and the wall behind the table.

Cubism as higher truth

This use of multiple perspectives became a hallmark of the Cubist style, but Braque and Picasso never explained why they employed this technique. One common contemporary interpretation argued that the use of multiple perspectives allows greater truth and accuracy than the traditional naturalistic style that had dominated art since the Renaissance. In 1912, the writer and art critic Jacques Rivière argued that linear perspective creates unrealistic distortions. For example, if we stand in the middle of railroad tracks, they appear to converge and meet at a point, when in fact they remain parallel.

François Bonvin’s painting of a violin shows how much the instrument is skewed and distorted when viewed in perspective. Parts nearer the viewer are larger than parts further away, and some parts are compressed by foreshortening while others are occluded entirely. Rivière wrote that such distortions are corrected in real life simply by moving around objects to see their true shapes.

A step to the right and a step to the left [can] complete our vision. The knowledge we have of an object is … a complex sum of perceptions … the object must always be presented from the most revealing angle.[3]

Braque represents the key parts of the violin from the most revealing angle. For example, the scroll is flipped to the side because if viewed from the front like the rest of the violin, it would not be visible at all. At the same time, though, if the scroll were viewed from the side, we would only see two of the tuning pegs, so Braque flips the view again to straight on so that all four pegs are visible.

Perspective is a deliberate lie

In 1912, the writer Olivier-Hourcade provided another example of how Cubist paintings correct the distortions of perspective:

The painter, when he has to draw a round cup, knows very well that the opening of the cup is a circle. When he draws an ellipse, therefore, he is not sincere, he is making a concession to the lies of optics and perspective, he is telling a deliberate lie.[4]

Look at all of the ellipses (flattened circles) in the Heda still-life above: the lip of the glass, the goblet, and the silver pedestal bowl, as well as the two pewter plates and the sliced lemon. All of these shapes are circles in real life; they only appear to be ellipses because of the angle from which they are viewed. The painter can correct this illusion simply by depicting these shapes from straight on, so the circle reveals its true shape.

Recognizing objects in Cubism

The subject of this still life may be difficult to discern, but with the help of the title we can begin to pick out the represented objects. The clarinet is the white rectangular shape in the left of the painting. Four finger holes extend up its length, which is shaded with chiaroscuro to suggest its tubular volume.

Note that while the bulk of the instrument is seen from the side, the opening at the base in the center of the painting is round, and a semicircle and schematic triangle at the other end by the edge of the canvas suggest the wedge-shaped cut out of the mouthpiece where the reed sits.

Above the clarinet’s finger holes, we can see a wine bottle with schematic, squared-off shoulders. Its transparency is indicated by the fact that we can see the clarinet through it. Notice that here, too, while we see the bulk of the bottle from the side, Braque has rendered the bottle’s mouth as a circle, as though seen from above, while a quarter-circle indicates the round base below.

With familiarity, we can begin to recognize objects in Cubist still-lifes even when they are not explicitly mentioned in the title. In the upper right quadrant of this painting there is a stemmed glass, again seen mostly from the side, but circles at the base, lip, and stem indicate the perfect roundness of those parts.

An art of conception, not perception

Jacques Rivière also argued that monochromatic color and inconsistent lighting are more truthful means to depict reality than traditional naturalism. As the Impressionists had demonstrated, the appearance of objects changes radically in different kinds of light.

Monochromatic color eliminates the variables of lighting to represent objects in their true form, as we know them to be, rather than showing them distorted by our vision. For this reason, Cubism was often seen as an art of conception rather than perception. Cubist paintings represented the composite idea of objects that we have in our heads, rather than rendering objects from one point of view, at one moment in time, and in one kind of light.

Cubism vs. illusionism

Braque and Picasso were well aware of how revolutionary their new way of representing objects was. As if marking the very different approaches to “realism” employed by Cubism and traditional naturalism, Braque painted a nail in the top center of Pitcher and Violin. Although it is rendered in a relatively cursory manner, its darkness and cast shadow make it appear at first sight as though it were a real nail pinning the painting to the wall.

This refers to a tradition of nineteenth-century trompe l’oeil painting that was the culmination of Renaissance naturalism. Trompe l’oeil paintings are so detailed and convincing that the viewer is fooled into thinking they are real.

Everything in this Harnett still life is painted: the violin, the door, the rusty hinges and nails, the lock, and even the wooden frame. Although this is the style that is usually taken as being the most “realistic,” it is in fact an illusion: it’s only paint on canvas. The use of multiple perspectives to show objects’ true shapes is arguably more true to reality.

Incomprehensible fins

The idea of Cubism as a more truthful representation of objects based on the use of multiple perspectives to build up a composite, conceptual representation was one of the dominant interpretations of the movement. It does not, however, fully account for what we see in the works, and it should be remembered that Braque and Picasso did not articulate or endorse this interpretation.

One thing that this interpretation does not account for is what can be called the “background noise” of Cubist paintings. While some shapes in Braque’s Pitcher and Violin and Clarinet and Bottle can be seen as articulating the shapes of those objects from multiple perspectives, others appear to be just arbitrary fragments. Also, as the style of Cubism evolved, Braque and Picasso broke objects up into smaller and smaller facets, until they are virtually unrecognizable in a shallow plane of monochromatic shards.

More oddly still, not only are the objects themselves faceted, it appears as though the empty space between them has also been shattered into facets. In some works, paint is applied in an almost brick-like fashion, further contributing to the background noise, until only a few clues (and the titles) hint at what is being represented.

Rivière found such paintings perplexing:

To each object they add the distance which separates it from neighboring objects … and in this way they show it prolonged in all directions and armed with incomprehensible fins. The intervals between forms—all the empty parts of the picture, all the places in it occupied by nothing but air, find themselves filled up by a system of walls and fortifications.[5]

Although this is a fairly accurate description of late Cubist painting, Rivière was unable to explain its motivations and claimed that these were “mistakes.” His highly rational view of Cubism led him to dismiss the elements of the style that did not conform to his ideas. Rivière’s “multiple perspectives as higher truth” interpretation is compelling, and as we have seen backed by some visual evidence, but there are clearly other facets to Picasso’s and Braque’s Cubism.

Synthetic Cubism, Part I

Starting in 1912, surprising new elements begin to turn up in works by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque: cut-up pieces of newspaper, wallpaper, construction paper, cloth, and even rope. Although the resulting collages are visually very different from the largely monochromatic oil paintings most commonly associated with the movement, they are still considered to be part of Cubism.

Partly this is because these works often included drawings that use techniques associated with Cubism, such as deconstructing objects into fragmented, angular forms seen from multiple perspectives. Beyond this similarity, though, there is also another, more conceptual one. This new phase of Cubism is also dedicated to exploring the ambiguities of representation, now on an even wider scale.

Fruit Dish and Glass is Braque’s first work using papier collé (pasted paper), a subset of collage made using only paper. Picasso’s first collage, Still Life with Chair Caning preceded Braque’s Fruit Dish and Glass by a few months and was made from a variety of materials including oilcloth and rope. Papier collé was a central medium in the second phase of Braque’s and Picasso’s joint Cubist investigations commonly known as Synthetic Cubism.

Retreat from abstraction

During this phase both artists retreated from the verge of total abstraction they had reached in their late Analytic Cubist paintings. Synthetic Cubist works use multiple forms of representation, combining the abstracted forms of Analytic Cubism with color, collage, and even sometimes naturalistic representations, to create a complex whole.

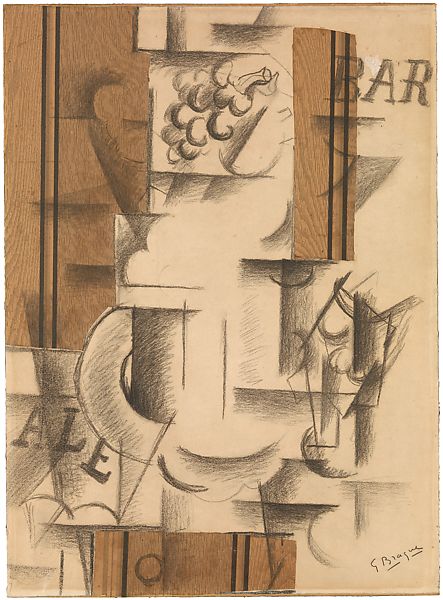

In Fruit Dish and Glass, Braque combines Cubist drawing with illusionistic representation, words, and decorative paper printed with a wood grain pattern (faux bois). At the top we see a bunch of grapes drawn relatively naturalistically, with light and shade defining its three-dimensional forms. The remaining still-life objects are depicted in an Analytic Cubist style that deconstructs them into arcs, cylinders, and flat planes representing a fruit dish, plates, and glasses on a table. The words “BAR” and “ALE” are frequently seen on signs and labels in cafés and indicate the general location of the still life.

References to traditional illusionism

Charcoal drawing extends over the strips of wood grain paper that frame and anchor the central forms. The two vertical strips in the upper portion represent wood paneling on a café wall behind the still life, while the horizontal strip below represents a wooden table supporting the dishes and fruit. A circle drawn on the lower strip of wood grain paper suggests the round knob of a drawer pull. This is a reference to illusionistic paintings, which often depict handles and knobs facing the viewer to enhance the sense of the objects being real and within easy reach.

The naturalistic grapes framed by lines and pasted paper at the top of the work are also a specific reference to the Western tradition of illusionistic representation. A famous story from Ancient Greece describes how the painter Zeuxis was so skilled an artist that birds tried to eat the grapes he painted. Braque centers his drawn grapes as a well-known example of traditional naturalism and then surrounds them with alternative strategies of representation.

Signifying real objects by other means

The Cubist drawings of suggestive geometric forms are, like the words BAR and ALE, a means of referring to or signifying real objects. If we know the language we know what a word signifies; this is true of French and English, and it is (at least theoretically) true of Cubist forms as well. Once we are aware of Cubist conventions for drawing we can recognize that certain relationships of lines and shapes signify fruit, a glass, or a face. The wood grain paper is also a means of signification. The represented texture refers to the physical materials in the scene, providing further information.

In addition, wood grain paper is, like the drawn grapes, an illusion. The naturalistically depicted grapes represent the central achievement of the European fine art tradition. The wood grain paper is, by contrast, a cheap mass-produced item used for decorative purposes. Its presence undermines the exalted value of artistic skill in creating illusionistic representations, and demonstrates another feature of synthetic Cubism: the collapse of distinctions between “high” art and the cheap, ephemeral materials and techniques of mass-produced design.

A kind of certainty

Braque later wrote:

The papiers collés in my drawings have also given me a kind of certainty.[6]

This is generally understood to mean that they allowed him a way to retreat from the increasingly unmoored abstraction of late Analytic Cubism and anchor his works more solidly in relation to reality. The vaporous spaces and ambiguous forms of Analytic Cubist paintings like The Portuguese are, however, replaced by a different type of ambiguity resulting from the complex and shifting relationships of disparate materials and modes of signification.

Braque’s association of papiers collés with certainty should also be understood in terms of literalism and materiality. Picasso and Braque often employed collage elements as a shortcut means to represent objects. A newspaper in a still life of a café table will be represented by simply gluing newspaper to the picture plane, rather than painstakingly imitating its appearance using paint. Similarly, literal wallpaper is used to represent the presence of wallpaper in the scene, and the actual label is used to show a label on a bottle of wine. This is a form of playful one-upmanship of the Western tradition of naturalistic depiction: the artist now offers reality itself, rather than illusion.

Collage elements also enhance the physical and tactile qualities of the artwork, which increasingly interested both Braque and Picasso. During this period they both also made sculptures and created pronounced surface textures in their paintings by adding sand, sawdust and other grainy materials to paint.

The strips of wood-grain paper in Fruit Dish and Glass confront the viewer with powerful dark shapes, which create a visually strong frame for the more immaterial charcoal drawing on white paper. In addition, the way the drawing continues onto the pasted paper enhances the typically Cubist interest in the tension between literal flatness and represented spatial depth.

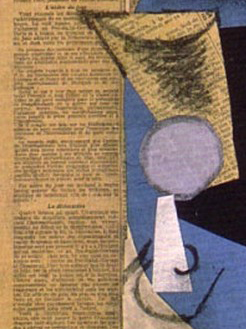

Multiple readings

In Siphon, Glass, Newspaper and Violin, Picasso displays the multiple ways charcoal drawing and papier collé can be used to represent objects. For example, on the left newspaper is cut into the shape of a siphon, while on the right it is used as a surface for drawings of a glass and part of a violin. Its edges also define the left side of the violin’s upper body and neck.

Analytic cubist techniques are used to depict the glass, violin, and top of the siphon from multiple perspectives, while on the far right, paper painted with illusionistic wood grain indicates the violin’s material. In the center the word ‘JOURNAL’ (the French word for newspaper) cut from a newspaper’s masthead represents that object in a particularly direct and literal way. Although we are not offered a coherent visual illusion of the objects in the title, these multiple media and representational strategies combine to give us all of the relevant information.

Papier collé and collage not only anchored Cubist forms more firmly as distinct material objects, they also gave the artists a particularly rich means for generating multiple possibilities of meaning through a combination of media, representational strategies, and suggestive shapes and their formal relationships. Collage shapes, materials, colors, and words all contribute to the complex significations that proliferate in Synthetic Cubism.

Synthetic Cubism, Part II

Pablo Picasso’s Guitar, Sheet Music and Glass is generally thought to have been made as a response to Georges Braque’s Fruit Dish and Glass. Both works bring a new tool into the already-complex collection of Cubist techniques of representation — the use of collage.

A wealth of associations

The subject of Picasso’s Guitar, Sheet Music and Glass is familiar from earlier Analytic Cubist paintings, which frequently depict café tables with drinks, newspapers, and musical instruments. Here, however, the abstracted geometric forms of Analytic Cubism are limited to the charcoal drawing of the glass on paper pasted on the right. It is one element in the collage, which includes seven different types of paper arranged on a wallpaper ground.

The pattern of the wallpaper is a diagonal lattice that frames flowers and recalls the overall patterns of lattices and grids that structure earlier Analytic Cubist paintings such as Braque’s Piano and Mandola.

While Braque’s Fruit Dish and Glass used only one type of pasted paper (the printed wood grain), Picasso uses many, and demonstrates that a wealth of associations can be generated from their juxtaposition.

Patterns of formal relations

An intricate pattern of formal relations is created between the varied shapes and colors of the pasted paper, which also generate a complex set of possible readings. The guitar is signified by multiple cut-paper elements.

On the left, the hand-painted wood grain paper cut into a double curve suggests the material and shape of the guitar’s body. A vertical trapezoid of blue paper is the neck in perspective, while the shallow black curve below stands for both the bottom of the guitar and the leading edge of the circular table on which the still-life sits.

In the center of the image, the white paper circle representing the sound hole in the guitar body looks like a hole cut out of the picture, while the fragment of sheet music simultaneously refers to itself, and to the sounds emanating from the instrument.

The glass drawn in charcoal is somewhat overwhelmed by the strong shapes of the pasted papers, but its ghostly appearance, as well as the semi-transparency of the paper on which it is drawn, suggests the transparency of glass. It is brought into the composition by the use of a visual rhyme — the circular lip of the glass directly echoes the white circle of pasted paper to the left.

The importance of text

One topic of debate among art historians has been the importance of the legible texts in Cubist collages. In this instance, it is generally agreed that the newspaper text in the lower left is relevant. The headline “La Bataille s’est engagé” (the battle has begun) is from an article about the Balkan War, but it is often interpreted as a competitive challenge to Braque, referring to the use of papier collé. In that reading, this work is a direct response to, and attempt to one-up, Braque’s Fruit Dish and Glass.

The truncated masthead of the newspaper “LE JOU” (short for le journal, French for “the newspaper”) is also meaningful. It appears in many Cubist works and not only signifies the newspaper’s presence in the still life, but also a pun on the French words for “to play” (jouer) and “toy” (le jouet). This is a verbal echo of the many formal rhymes and visual puns that appear in Synthetic Cubist works. These allow for multiple readings of individual elements and the relationships between them.

In Guitar, Sheet Music and Glass, for example, “LE JOU” also recalls the French word for day (le jour), and suggests another reading for the forms in the work. The circle of white paper overlapping the trapezoid of blue paper above it can be interpreted as representing not only a guitar’s sound hole and neck, but as the sun rising into the sky at the beginning of a new day. Battles often begin at dawn, and the paired juxtaposition of the papier collé guitar and the Analytic Cubist drawing of a glass suggests a competition between older and newer Cubist techniques.

Political references

Most early discussions of Cubist collages stressed their formal innovations and the novel representational strategies they employed. More recently, however, some art historians have looked more closely at the texts of the newspaper clippings in Picasso’s works and discovered references to his political interests.

Still Life with Bottle of Suze is another work that uses legible clippings of articles about the contemporary Balkan war. This one also includes a clipping about a socialist demonstration against that war held in a Paris suburb. When asked about it years later Picasso said he used that particular clipping because it was a huge event and to show that he was against the war.

While it is unlikely that Picasso expected viewers to carefully read the fine print text in the newspaper clippings he used, headlines and sub-headers often stand out and appear to make relevant comments. In Still Life with Bottle of Suze a bold face sub-header on the left, “La Dislocation”, is easily legible and placed next to the still-life objects that have been separated and dislocated by Cubist representational techniques.

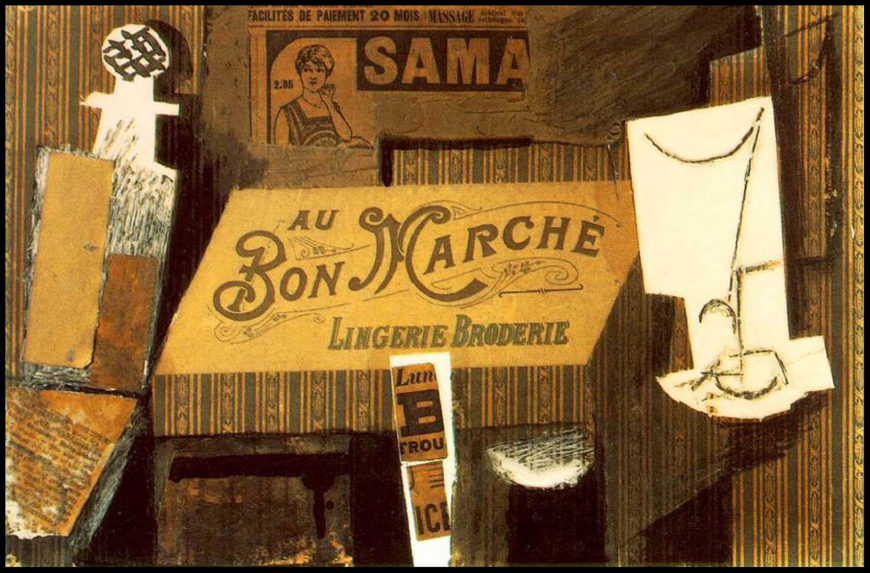

An art of ordinary activities and cheap materials

Most early Cubist collages depict still-life subjects, usually the types of objects found on café tables. They represent the ordinary places where the artists would have a drink, listen to a musical act, read a newspaper, and meet their friends. Newspaper clippings represent the sort of topical events discussed in cafés. Preserved in the artworks, the newspapers and other ordinary non-art materials such as wallpaper, labels, tickets, etc. now seem like mementos of a specific time and place.

In their collages Picasso and Braque avoided conventional, often expensive, art materials and overt displays of technical skill that would indicate artistic training. Prior to its use by Braque and Picasso, collage was primarily a craft technique used by women and hobbyists in the 19th century to make scrapbooks. Collages are “poor” art works that do not employ the professional artist’s traditional manual skills.

Picasso’s Au Bon Marché proclaims its cheapness not only in its materials, but by its title as well. Bon marché is a French term meaning “good deal” or “cheap” as well as being the name of a prominent Paris department store. At the top of the collage, an advertisement for a rival Paris department store, Samaritaine, suggests another persistent theme of the collages: references to brand name products, mass media, advertisements, and commerce. Many artists, starting with the Dadaists during World War I and continuing to the present day, adopted the Cubists’ use of cheap found materials, employing them as a critical strategy to question the commercial values of the art world and modern society.

An enormous influence

For many people the appeal of early Cubist collage and papier collé is more intellectual than conventionally aesthetic. These works prompt the viewer to enjoy the multiple references and significations to be found in the combinations of forms and punning texts, rather than displaying the sensuous qualities of the painted surface or the artist’s skilled touch.

Despite its somewhat arcane intellectual appeal, however, Cubist collage had an enormous influence on modern art in the 20th century. Its employment of simplified planar forms was instrumental in the establishment of non-representational art, especially the geometric abstraction of movements such as Suprematism, Constructivism, De Stijl, Color Field painting, and Minimalism. And, the way the collages combine disparate found materials, refer to mass consumer culture, and collapse distinctions between ‘low’ and ‘high’ culture contributed to the development of Dada, Surrealism, assemblage, Pop art, and the various trends associated with post-modernism.

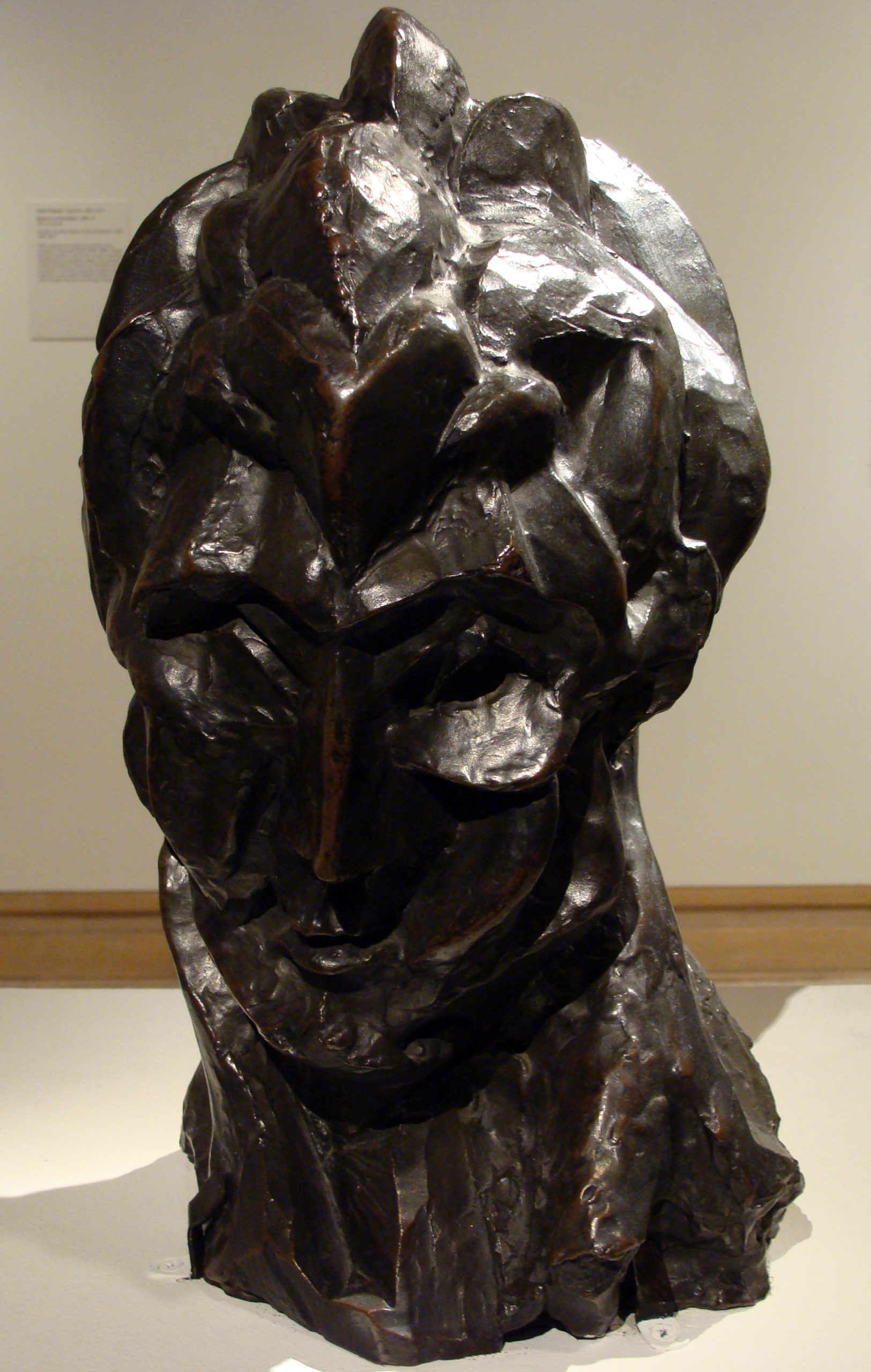

Cubist Sculpture I

Picasso’s Guitar hangs from the wall like a painting or a real guitar, but we wouldn’t mistake it for either one. Unlike a painting, it’s a complex three-dimensional object, and it’s clearly not a functional guitar to be played. It’s an abstract representation of a guitar, an artwork, but one that doesn’t fit neatly into the tradition of Western representational sculpture. It is not a solid mass carved from marble or cast in bronze; it is not on a pedestal, nor is it attached to a background like a relief.

An unprecedented subject

Furthermore, the guitar as a subject is unprecedented in a sculptural tradition almost exclusively devoted to representations of human and animal figures. Picasso’s own earliest Cubist-based sculptures were of a woman’s head.

Guitar represents Picasso’s attempt to expand his Cubist investigations of the ambiguities of represented form and space into three dimensions. Both Picasso and Braque began making paper and cardboard Cubist sculptures of still-life objects around the same time that they began making collages.

None of these early sculptures survive, and only a few photographs document their existence. They were, however, seen by other artists who visited Picasso’s and Braque’s studios. Vladimir Tatlin’s counter-reliefs were made in direct response to these early Cubist sculptures.

Innovations derived from an African mask

The surviving sheet-metal Guitar in MoMA’s collection is a later version of a now lost cardboard model (also known as a maquette). It is an important work, not only because it is one of the earliest surviving Cubist sculptures by Picasso, but also because of what Picasso’s friend and art dealer D. H. Kahnweiler wrote about it. He claimed that the innovative treatment of forms in Guitar was directly derived from an African Grebo mask Picasso owned. In that mask the eyes are represented by projecting cylinders. Human eyes, of course, are recessed in the head and do not project out from the face. In Guitar Picasso used a similar strategy for representing the guitar’s sound hole as a tube projecting from the empty space at the base of the fretboard. Space becomes shaped forms, while solid forms—the body of the guitar in this case—become, in places, empty space.

Guitar follows the example of the Grebo mask in radically simplifying forms to basic geometric shapes and arranging them to convey information. We see the double curve of the guitar’s body in the flat frontal plane of the sculpture as well as a larger flat plane in the back. We also are shown the guitar’s hollowness by the rectangle cut into the guitar shape between the front and back curved planes. The cylinder projects from the center of this empty space; it is itself hollow, so it is both a projecting form and one signifying emptiness.

Kahnweiler explained that Picasso derived a crucial concept from the Grebo mask — that it was possible to use signs to represent things rather than imitating their appearance. This, far more than mere formal similarities, is central to understanding the way Picasso’s art as a whole was affected by insights prompted by African and Oceanic masks and sculptures. We recognize the facial features in the Grebo mask by the placement and relationship of the parts rather than their specific details. The mouth, for example, is simply a rectangle with stripes. Alone it would not be recognized as a mouth, but in the context of the mask it is a very effective representation of one.

A new type of sculpture

With Guitar, Picasso extended his collage explorations into three dimensions. By doing so he made a new type of sculpture, which is now called assemblage because it is assembled from multiple parts rather than formed as a single mass. The move into three dimensions added an important element to the work—cast shadows. These contribute to the visual complexity of Guitar by creating planes and patterns, and suggesting much greater depth and solidity than is actually created by the rather delicate metal planes. In this photograph the shadow projected on the wall to the left seems to represent the side of the guitar.

Of course, because it is a three dimensional object, the shadows projected by Guitar will change with changes in lighting. Shadows add an additional layer of complexity to Picasso’s Cubist investigation of the ambiguities that can arise from the juxtaposition of real things and their representations.

A workman’s lunch

Picasso’s Still Life is another Cubist sculpture attached to a wall that plays with reality and representation. The still life subject is unconventional for a sculpture. It represents a working man’s simple lunch of sausage and bread accompanied by a glass of wine and a knife. All of the elements are painted wood except for a real piece of tasseled upholstery fringe attached to the semicircular plane representing the table top. The bread and sausage are crudely painted imitations of the subject, the knife is a simplified basic form, while the wineglass is Cubist in style. A strip of wood painted with a repeating pattern represents a decorative railing on the wall.

The sculpture uses a real decorative object, the strip of upholstery tassels, in combination with representations of objects depicted with varying degrees of naturalism. Adding to the complex display of reality and illusion is the painted decorative railing, which is attached to the wall as part of the sculpture, but could be a “real” decorative railing on the gallery wall.

Despite the inclusion of real objects and the realistically painted bread and sausage, Picasso clearly wanted the viewer to see Still Life as art, a hand-made object. The semi-circular plane representing the table top does not project from the wall at 90 degrees; it is tipped down like the table tops in Cubist paintings and collages, and could not support a real glass or knife. The quality of the workmanship is intentionally crude and roughly finished, in keeping with the simple workman’s lunch depicted.

Fine art versus craft

Still Life leads us to consider different possible approaches to representation and decoration, fine art and craft, and what they signify. The work juxtaposes the crafts of woodworking and upholstering, both associated with working class labor, with the illusionistic representation of still life objects associated with fine art. In uniting these two very differently-valued types of craft labor Picasso calls into question the traditional high valuation of the fine arts in relation to the so-called crafts, as well as challenging established distinctions between fine art and decoration. Known for his working class sympathies, Picasso here seems to claim an affinity with the artisans who work in the decorating trades.

Although they were little known at the time they were made, the innovations of Picasso’s Cubist assemblages foreshadowed many developments of twentieth-century sculpture. His use of found materials, rejection of the traditional materials and techniques of European sculpture, and elimination of a clear distinction between artwork and object make his early Cubist assemblages important early contributions to the breakdown between art and life that would become a key theme of twentieth-century sculpture.

Cubist Sculpture II

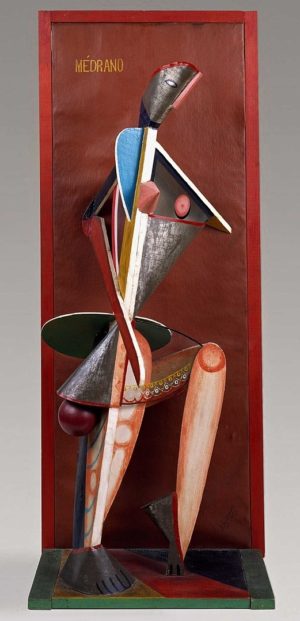

Cubism instigated significant developments in twentieth-century sculpture, challenging the European sculptural tradition in terms of form, media, and often subject matter. Alexander Archipenko’s Médrano II is an early example of the new approaches used by Cubist sculptors.

A circus performer

Médrano II is a representation of a woman made from simple shapes in a variety of materials. She looks like a jaunty doll dancing on a shelf. Her head is a piece of folded tin with a painted eye and red hairline and a thin piece of pink wood for a nose. A central wooden vertical supports glass, tin, and wood planes, which are cut into basic geometric shapes and painted in bright colors to represent her shoulders, arms, legs, and skirt. Two simplified wooden feet anchor the figure on a multicolored horizontal plane that projects like a shelf from a vertical red backdrop that frames the figure.

The title refers to the Médrano circus, which was frequented by many artists in the early 20th century, and indicates that the brightly painted figure is a circus performer. Her mobile stance with one leg bent on tiptoes and the inclusion of a ball below her skirt suggests the lighthearted attitude of an acrobat or juggler. The forms of Archipenko’s sculpture are similarly playful with repeated circles that seem to bounce through the figure, as well as the delicate pattern painted on the glass skirt, through which we can see the woman’s thigh.

Sculptures that hang from the wall

Médrano II is a rare surviving early Cubist sculpture that reflects the innovations of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque’s Synthetic Cubist collages and sculptures. Like them, Archipenko combines a variety of cheap materials, emphasizes repeated geometric shapes, and adopts a playful approach to representation and design. The presentation of the sculpture against a framing backdrop is also similar to Picasso’s early Cubist sculptures, which were frequently conceived as hanging from the wall like paintings. The subject of a female figure and the bright colors are, however, more comparable to the approaches used by the Salon Cubists, and Médrano II was, in fact, exhibited in the 1914 Salon des Indépendants.

Henri Laurens’ Head of a Woman also uses a Cubist assemblage technique, but it is a more abstract and formally ambitious work than Archipenko’s. Like the later Cubist paintings and collages of Braque and Picasso, the head is fractured into multiple abstract shapes that represent specific features by relationship and form. For example, we can recognize the central vertical white triangle as a nose and the white circle next to it as an eyeball, while zigzag edges in the plane above suggest hair. The sculpture successfully translates the ambiguities of Cubist representation into three dimensions; however, it was made to hang on a wall, and thus intended to be viewed from a restricted angle. Like Archipenko’s Médrano II, it does not exploit the full potential of sculpture’s three-dimensionality.

A more traditional approach

Archipenko also created several small freestanding bronze Cubist sculptures of women. In terms of medium, these were much more traditional than his Médrano II. They did, nevertheless, fully translate the Cubist approach into the three dimensions of sculpture. Walking Woman breaks down the mass of the body and incorporates space into the center of the form. The solid elements of the sculpture shape space, turning a void into an implied solid. The woman’s torso is defined by the conventional double curves that outline breasts, waist, and hips, but here they shape emptiness. Picasso used a similar strategy to define the body of the guitar in his collage Guitar, Sheet Music and Glass.

Archipenko’s Walking Woman is also reminiscent of the Analytic Cubist strategies used in paintings like Picasso’s Girl with a Mandolin, in which simplified, geometric body parts are fragmented and dissolved into the surrounding space. The figure is suggested in Archipenko’s sculpture, and some parts of it, like the head, legs and part of a skirt, can be identified with confidence, but others, like the arms, are missing or only indirectly suggested.

Classical references

Woman Combing Her Hair is much more traditional than Walking Woman despite the shaped void representing the woman’s head and neck. Archipenko used Cubist techniques here to create a decorative form with obvious classical references in both the contrapposto pose and the form. The truncated arm and breaks at the knees suggest the broken remains of Classical figures like the Venus de Milo.

A non-naturalistic concavity defines the inner thighs and pubic area, but the effect is still fundamentally naturalistic and sensual. The raised arm merging with the figure’s hair is a quotation of many images of Venus. In this work the innovations of Cubism are used to create a modernist update of a decorative table-top sculpture.

Jacques Lipchitz also made Cubist figure sculptures in the mid-1910s that participate in the contemporary trend to establish Cubism as a classical style. His Man with a Guitar and Man with a Mandolin abstract the figures into clusters of simple geometric planes. This approach is notably similar to Picasso’s contemporary Cubist figure paintings, such as Seated Man.

The technique of stone carving is traditional, and the soft white tones of Lipchitz’s figures reflect the classical tradition of Western sculpture. The figures themselves are radically abstracted, but the overall treatment of the sculptural form remains conventional. Lipchitz emphasizes sculptural mass, rather than integrating mass and space. Man with a Guitar stands on an integrated pedestal, a long-established mode of presentation. Like Archipenko’s more sensual figures of women, Lipchitz’s male musicians turn Cubism into a decorative style with classical overtones.

Cubism instigated two significant developments in twentieth century sculpture. The first, and more radical of the two, was the combination and assemblage of non-traditional materials to create objects that challenged the European sculptural tradition in terms of form, media, and often subject matter. This development led through Dada and Surrealism and on to the many art works of the later 20th century that challenged traditional conceptions of art.

The second development of Cubist sculpture was also extremely fertile. It was the establishment of a new abstract formal language for sculpture that retained the traditional Western conception of the art object as designed for aesthetic contemplation, while expanding its range into non-representational forms.

Pablo Picasso, Guernica

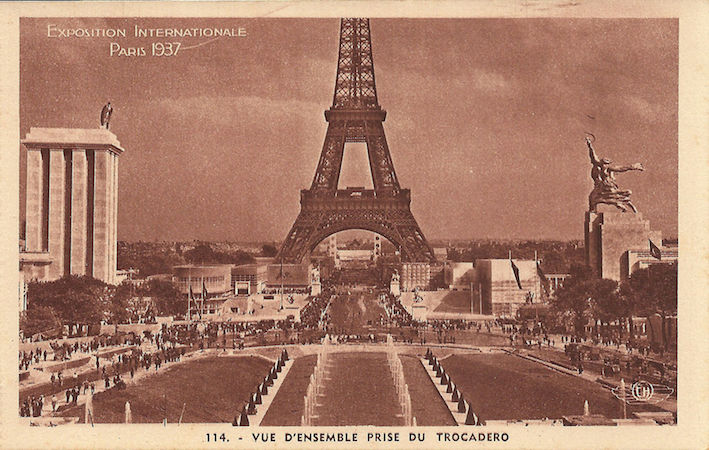

What would be the best way today to protest against a war? How could you influence the largest number of people? In 1937, Picasso expressed his outrage against war with Guernica, his enormous mural-sized painting displayed to millions of visitors at the Paris World’s Fair. It has since become the twentieth century’s most powerful indictment against war, a painting that still feels intensely relevant today.

Antiwar icon

Much of the painting’s emotional power comes from its overwhelming size, approximately eleven feet tall and twenty five feet wide. Guernica is not a painting you observe with spatial detachment; it feels like it wraps around you, immerses you in its larger-than-life figures and action. And although the size and multiple figures reference the long tradition of European history paintings, this painting is different because it challenges rather than accepts the notion of war as heroic. So why did Picasso paint it?

Commission

In 1936, Picasso (who was Spanish) was asked by the newly elected Spanish Republican government to paint an artwork for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 Paris World’s Fair. The official theme of the Exposition was a celebration of modern technology. Yet Picasso painted an overtly political painting, a subject in which he had shown little interest up to that time. What had happened to inspire it?

Crimes against humanity: an act of war

In 1936, a civil war began in Spain between the democratic Republican government and fascist forces, led by General Francisco Franco, attempting to overthrow them. Picasso’s painting is based on the events of April 27, 1937, when Hitler’s powerful German air force, acting in support of Franco, bombed the village of Guernica in northern Spain, a city of no strategic military value. It was history’s first aerial saturation bombing of a civilian population. It was a cold-blooded training mission designed to test a new bombing tactic to intimidate and terrorize the resistance. For over three hours, twenty five bombers dropped 100,000 pounds of explosive and incendiary bombs on the village, reducing it to rubble. Twenty more fighter planes strafed and killed defenseless civilians trying to flee. The devastation was appalling: fires burned for three days, and seventy percent of the city was destroyed. A third of the population, 1600 civilians, were wounded or killed.

Picasso hears the news

On May 1, 1937, news of the atrocity reached Paris. Eyewitness reports filled the front pages of local and international newspapers. Picasso, sympathetic to the Republican government of his homeland, was horrified by the reports of devastation and death. Guernica is his visual response, his memorial to the brutal massacre. After hundreds of sketches, the painting was done in less than a month and then delivered to the Fair’s Spanish Pavilion, where it became the central attraction. Accompanying it were documentary films, newsreels and graphic photographs of fascist brutalities in the civil war. Rather than the typical celebration of technology people expected to see at a world’s fair, the entire Spanish Pavilion shocked the world into confronting the suffering of the Spanish people.

Later, in the 1940s, when Paris was occupied by the Germans, a Nazi officer visited Picasso’s studio. “Did you do that?” he is said to have asked Picasso while standing in front of a photograph of the painting. “No,” Picasso replied, “you did.”

World traveler

When the fair ended, the Spanish Republican forces sent Guernica on an international tour to create awareness of the war and raise funds for Spanish refugees. It traveled the world for 19 years and then was loaned for safekeeping to The Museum of Modern Art in New York. Picasso refused to allow it to return to Spain until the country “enjoyed public liberties and democratic institutions,” which finally occurred in 1981. Today the painting permanently resides in the Reina Sofia, Spain’s national museum of modern art in Madrid.

What can we see?

This painting is not easy to decipher. Everywhere there seems to be death and dying. As our eyes adjust to the frenetic action, figures begin to emerge. On the far left is a woman, head back, screaming in pain and grief, holding the lifeless body of her dead child. This is one of the most devastating and unforgettable images in the painting. To her right is the head and partial body of a large white bull, the only unharmed and calm figure amidst the chaos. Beneath her, a dead or wounded man with a severed arm and mutilated hand clutches a broken sword. Only his head and arms are visible; the rest of his body is obscured by the overlapping and scattered parts of other figures. In the center stands a terrified horse, mouth open screaming in pain, its side pierced by a spear. On the right are three more women. One rushes in, looking up at the stark light bulb at the top of the scene. Another leans out of the window of a burning house, her long extended arm holding a lamp, while the third woman appears trapped in the burning building, screaming in fear and horror. All their faces are distorted in agony. Eyes are dislocated, mouths are open, tongues are shaped like daggers.

Color

Picasso chose to paint Guernica in a stark monochromatic palette of gray, black and white. This may reflect his initial encounter with the original newspaper reports and photographs in black and white; or perhaps it suggested to Picasso the objective factuality of an eye witness report. A documentary quality is further emphasized by the textured pattern in the center of the painting that creates the illusion of newsprint. The sharp alternation of black and white contrasts across the painting surface also creates dramatic intensity, a visual kinetic energy of jagged movement.

Visual complexity

On first glance, Guernica’s composition appears confusing and chaotic; the viewer is thrown into the midst of intensely violent action. Everything seems to be in flux. The space is compressed and ambiguous with the shifting perspectives and multiple viewpoints characteristic of Picasso’s earlier Cubist style. Images overlap and intersect, obscuring forms and making it hard to distinguish their boundaries. Bodies are distorted and semi-abstracted, the forms discontinuous and fragmentary. Everything seems jumbled together, while sharp angular lines seem to pierce and splinter the dismembered bodies. However, there is in fact an overriding visual order. Picasso balances the composition by organizing the figures into three vertical groupings moving left to right, while the center figures are stabilized within a large triangle of light.

Symbolism

There has been almost endless debate about the meaning of the images in Guernica. Questioned about its possible symbolism, Picasso said it was simply an appeal to people about massacred people and animals. ”In the panel on which I am working, which I call Guernica, I clearly express my abhorrence of the military caste which has sunk Spain into an ocean of pain and death.” The horse and bull are images Picasso used his entire career, part of the life and death ritual of the Spanish bullfights he first saw as a child. Some scholars interpret the horse and bull as representing the deadly battle between the Republican fighters (horse) and Franco’s fascist army (bull). Picasso said only that the bull represented brutality and darkness, adding “It isn’t up to the painter to define the symbols. Otherwise it would be better if he wrote them out in so many words. The public who look at the picture must interpret the symbols as they understand them.”

In the end, the painting does not appear to have one exclusive meaning. Perhaps it is that very ambiguity, the lack of historical specificity, or the fact that brutal wars continue to be fought, that keeps Guernica as timeless and universally relatable today as it was in 1937.

- 1. Gertrude Stein, Picasso (London: BT Batsford, LTD, 1938); reprinted by Dover Publications, 1984, p. 8. ↵

- 1. As quoted in William Rubin, Picasso and Braque: Pioneering Cubism, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1989, p.353. ↵

- Jacques Rivière, “Present Tendencies in Painting” (1912), as translated in Edward Fry, ed., Cubism (New York and Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1966), p. 77. ↵

- Olivier-Hourcade, “The Tendency of Contemporary Painting” (1912), as translated in Fry, Cubism, p. 74. ↵

- Jacques Rivière, “Present Tendencies in Painting” (1912), as translated in Edward Fry, ed., Cubism, p. 79. ↵

- Georges Braque, “Thoughts on Painting” (1917) ↵

traveling circus performers

a 16th century Italian performing tradition with stock characters, such as Harlequin, who wears a colorful diamond-patterned suit

the (often problematic) belief that, lacking the corrupting influence of European civilization, non-western peoples were more in tune with the primal elements of nature

a style developed by Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso and characterized by its nearly-monochromatic palette, and fragmented depictions showing objects from multiple perspectives

a system for depicting space that is based on the optical illusion that parallel lines seem to converge as they recede into the distance

artworks depicting an often carefully-arranged collection of stationary objects—typically flowers, fruit, and/or serving ware

characterized by the use of just one color

from the French for "tricking the eye," an extremely illusionistic and detailed depiction of three-dimensional space designed to fool viewers into thinking the objects shown are real

from the French coller, "to stick," an artwork that includes pasted pieces of material: paper, cloth, clippings from newspapers or magazines, etc.

French, "pasted paper," a subset of collage made using only paper.

the second phase of Braque and Picasso's Cubist investigations, involving more color than Analytic Cubism and often featuring collage

French, "fake wood"; decorative paper printed with a wood grain pattern

analysis of a work of art based on its form rather than its subject matter or historical context

a scale model for a later sculpture, often made out of simple material, like cardboard

sculpture assembled from pre-existing pieces or found objects