Reshaping the world

When you think of maps, what comes to mind? An informative document used by travelers? Demarcations of national borders and geographic features? At the very least, we might think of some factual representation of the world, not one that is fictitious or subjective.

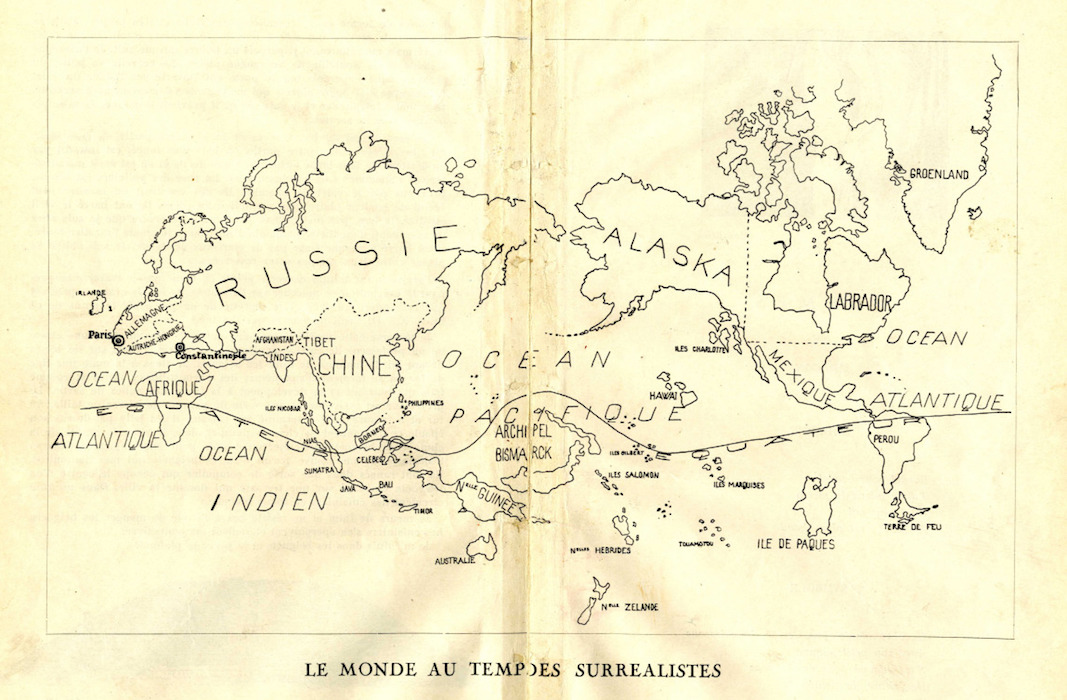

Imagine a map of the world. Now take a moment to examine the following map, created by members of the Surrealist movement and published in the Belgian journal Variétés in June 1929.

This anonymous map might seem unsettling; it emphasizes certain areas while removing others, and changes dramatically the size of landmasses. How is this map different from the world we know? And, although it might seem like an odd place to begin, what can it tell us about the ideas and approaches of the Surrealists?

Psychic freedom

Historians typically introduce Surrealism as an offshoot of Dada. In the early 1920s, writers such as André Breton and Louis Aragon became involved with Parisian Dada. Although they shared the group’s interest in anarchy and revolution, they felt Dada lacked clear direction for political action. So in late 1922, this growing group of radicals left Dada, and began looking to the mind as a source of social liberation. Influenced by French psychology and the work of Sigmund Freud, they experimented with practices that allowed them to explore subconscious thought and identity and bypass restrictions placed on people by social convention. For example, societal norms mandate that suddenly screaming expletives at a group of strangers—unprovoked, is completely unacceptable.

Surrealist practices included “waking dream” séances and automatism. During waking dream seances, group members placed themselves into a trance state and recited visions and poetic passages with an immediacy that denied any fakery. (The Surrealists insisted theirs was a scientific pursuit, and not like similar techniques used by Spiritualists claiming to communicate with the dead.) The waking dream sessions allowed members to say and do things unburdened by societal expectations; however, this practice ended abruptly when one of the “dreamers” attempted to stab another group member with a kitchen knife. Automatic writing allowed highly trained poets to circumvent their own training, and create raw, fresh poetry. They used this technique to compose poems without forethought, and it resulted in beautiful and startling passages the writers would not have consciously conceived.

Envisioning Surrealism: automatic drawing and the exquisite corpse

In the autumn of 1924, Surrealism was announced to the public through the publication of André Breton’s first “Manifesto of Surrealism,” the founding of a journal (La Révolution surréaliste), and the formation of a Bureau of Surrealist Research. The literary focus of the movement soon expanded when Max Ernst and other visual artists joined and began applying Surrealist ideas to their work. These artists drew on many stylistic sources including scientific journals, found objects, mass media, and non-western visual traditions. (Early Surrealist exhibitions tended to pair an artist’s work with non-Western art objects). They also found inspiration in automatism and other activities designed to circumvent conscious intention.

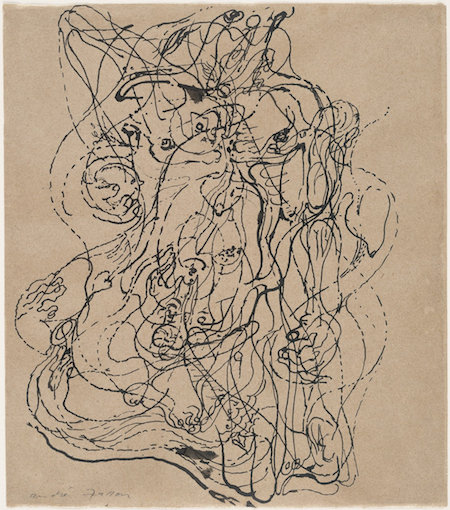

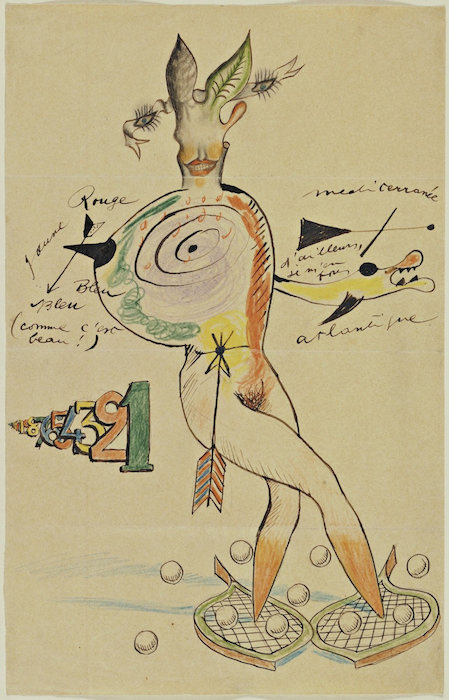

Surrealist artist André Masson began creating automatic drawings, essentially applying the same unfettered, unplanned process used by Surrealist writers, but to create visual images. In Automatic Drawing (left), the hands, torsos, and genitalia seen within the mass of swirling lines suggest that, as the artist dives deeper into his own subconscious, recognizable forms appear on the page.

Another technique, the exquisite corpse, developed from a writing game the Surrealists created. First, a piece of paper is folded as many times as there are players. Each player takes one side of the folded sheet and, starting from the top, draws the head of a body, continuing the lines at the bottom of their fold to the other side of the fold, then handing that blank folded side to the next person to continue drawing the figure. Once everyone has drawn her or his “part” of the body, the last person unfolds the sheet to reveal a strange composite creature, made of unrelated forms that are now merged. A Surrealist Frankenstein’s monster, of sorts.

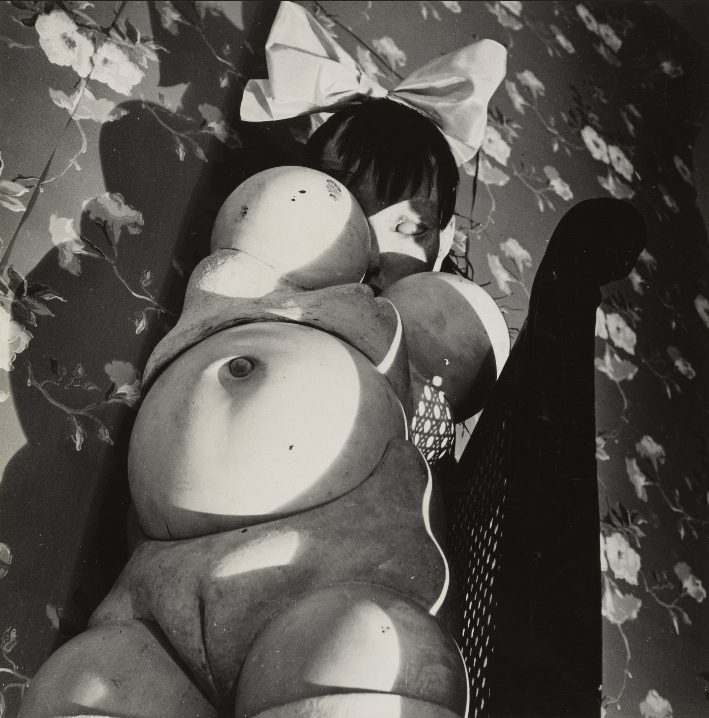

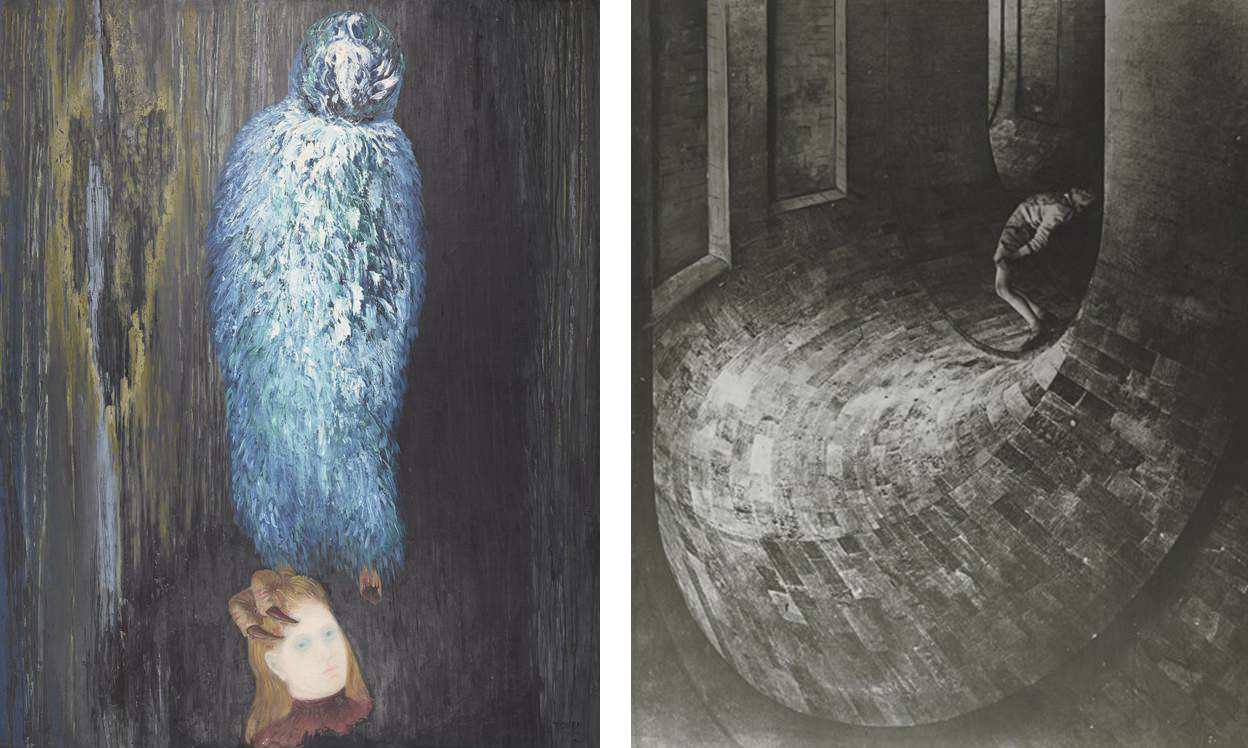

Whereas automatic drawing often results in vague images emerging from a chaotic background of lines and shapes, exquisite corpse drawings show precisely rendered objects juxtaposed with others, often in strange combinations. These two distinct “styles,” represent two contrasting approaches characteristic of Surrealists art, and exemplified in the early work of Yves Tanguy and René Magritte.

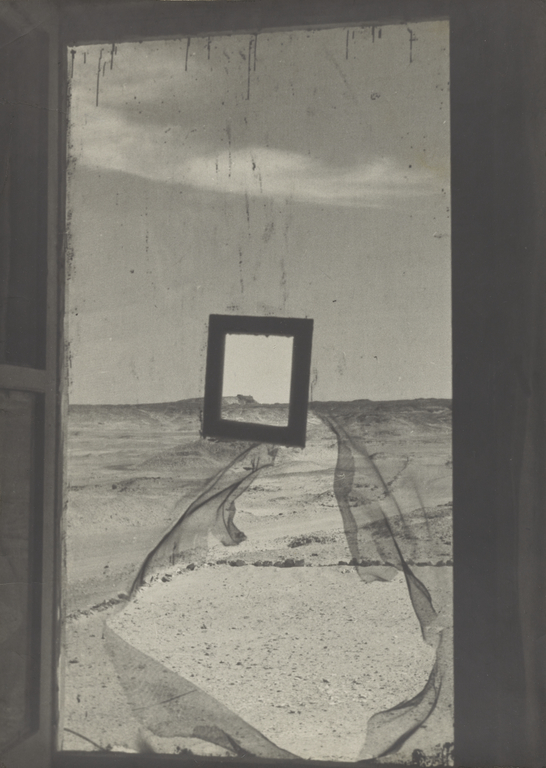

Tanguy began his painting Apparitions (left) using an automatic technique to apply unplanned areas of color. He then methodically clarified forms by defining biomorphic shapes populating a barren landscape. However, Magritte employed carefully chosen, naturalistically-presented objects in his haunting painting, The Central Story. The juxtaposition of seemingly unrelated objects suggests a cryptic meaning and otherworldliness, similar to the hybrid creatures common to exquisite corpse drawings. These two visual styles extend to other Surrealist media, including photography, sculpture, and film.

The Surrealist experience

Today, we tend to think of Surrealism primarily as a visual arts movement, but the group’s activity stemmed from much larger aspirations. By teaching how to circumvent restrictions that society imposed, the Surrealists saw themselves as agents of social change. The desire for revolution was such a central tenet that through much of the late 1920s, the Surrealists attempted to ally their cause with the French Communist party, seeking to be the artistic and cultural arm. Unsurprisingly, the incompatibility of the two groups prevented any alliance, but the Surrealists’ effort speaks to their political goals.

In its purest form, Surrealism was a way of life. Members advocated becoming flâneurs–urban explorers who traversed cities without plan or intent, and they sought moments of objective chance—seemingly random encounters actually fraught with import and meaning. They disrupted cultural norms with shocking actions, such as verbally assaulting priests in the street. They sought in their lives what Breton dubbed surreality, where one’s internal reality merged with the external reality we all share. Such experiences, which could be represented by a painting, photograph, or sculpture, are the true core of Surrealism.

The “Nonnational boundaries of Surrealism”[1]

Returning to The Surrealist Map of the World, let’s reconsider what it tells us about the movement. Shifts in scale are evident, as Russia dominates (likely a nod to the importance of the Russian Revolution). Africa and China are far too small, but Greenland is huge. The Americas are comprised of Alaska (perhaps another sly reference to Russia’s former control of this territory), Labrador, and Mexico, with a very small South America attached beneath. The United States and the rest of Canada are removed entirely. Much of Europe is also gone. France is reduced to the city of Paris, and Ireland appears without the rest of Great Britain. The only other city clearly indicated is Constantinople, pointedly not called by its modern name Istanbul. An anti-colonial diatribe, the Surrealists’s map removes colonial powers to create a world dominated by cultures untouched by western influence and participants in the Communist experiment. It is part utopian vision, part promotion of their own agenda, and part homage to their influences.

It also reminds us that Surrealism was an international movement. Although it was founded in Paris, pockets of Surrealist activity emerged in Belgium, England, Czechoslovakia, Mexico, the United States, other parts of Latin America, and Japan. Although Surrealism’s heyday was 1924 to the end of the 1940s, the group stayed active under Breton’s efforts until his death in 1966. An important influence on later artists within Abstract Expressionism, Art Brut, and the Situationists, Surrealism continues to be relevant to art history today.

Surrealist Techniques: Subversive Realism

The omnipotence of the dream

A central approach of Surrealist visual art was derived from André Breton’s assertion of “the omnipotence of the dream” in the first Surrealist Manifesto. Following the ideas of Sigmund Freud, the Surrealists saw dreams as visual representations of unconscious thoughts and desires. In their first magazine, La Révolution Surréaliste, they published accounts of their own dreams and reproductions of art that seemed to record dream images, notably the paintings of Giorgio de Chirico.

In addition to the dream-like atmosphere of de Chirico’s work, the Surrealists were attracted to what are often called its literary qualities. The strange juxtaposition of female nude, bananas, and train in The Uncertainty of the Poet seems like a literal illustration of the discordant imagery of a modern poem. In addition, the erotic symbolism of the image conforms to Freud’s belief in the central importance of sexuality in the unconscious.

Rejecting the formal concerns of modern art

In claiming de Chirico’s pre-war work as exemplary, the Surrealists implicitly rejected modern art’s emphasis on formal innovation. De Chirico’s use of linear perspective, his inexpressive representation of objects, and his lack of interest in the material qualities of paint all seemed to revive the outdated naturalistic conventions of pre-modern painting, as did his use of complex, symbolic subject matter.

For the Surrealists de Chirico’s style was irrelevant; what mattered to them was his ability to represent unconscious dream images. They were interested in the subject of his painting, not how it was painted. In their willingness to elevate subject matter over painting style and technique the Surrealists explicitly placed themselves outside of what they considered were the limiting concerns of established modern art. In return, many critics (and later art historians) attacked the Surrealists for failing to understand and appreciate the formal achievements of modern art.

Because the movement was initiated and led by writers, Surrealist art was often considered to be literary and illustrative rather than a properly modern visual art. This overlooked the fact that many prominent Surrealist artists, including André Masson, Joan Miró, and Max Ernst, frequently employed modern styles and developed innovative artistic techniques.

For the Surrealists, an artist’s style and technique were the means to concretize inspired thinking, the creative activity of the unconscious. Whether those means were traditional naturalism or the more abstract innovations of modern art was not important as long as they were effective. The use of meticulous naturalistic techniques — traditionally employed to represent the accepted “reality” of the external world — demonstrated the equal reality of the unconscious world revealed by Surrealism.

A window into another world

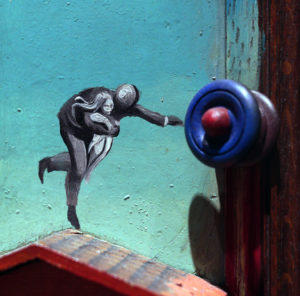

The complexity of the Surrealists’ challenge to modernist values can be appreciated by considering Max Ernst’s Two Children Threatened by a Nightingale. This painting was one of the first works by a Surrealist artist reproduced in the group’s journal, La Révolution Surréaliste. It combines echoes of de Chirico’s classical architecture and deep perspectival space with an incomprehensible nightmarish scene of violence in the foreground. Small wooden elements are attached to the painting to form a building, gate, and doorknob. The title is handwritten on the edge of the frame, which connects the painted world to the world of the viewer.

Ernst’s combination of painting, writing, collage, and relief sculpture disrupts the established categories of the individual arts as much as the image defies rational explanation. The painting is no longer simply a flat plane covered by colors, it has returned to its pre-modernist role as a window into another world, and that world is one into which we as viewers are invited. The gate on the left has swung open towards us, and the man running on the roof of the building at the right reaches for the “doorknob” on the frame that separates our world from his.

For the Surrealists who desired the complete breakdown of distinctions between art and life, dream and reality, Ernst’s disruption of pictorial boundaries meant far more than a challenge to the conventional distinctions between the different arts. It was the means to enter an entirely new world and heralded the concrete realization of Surrealism’s ultimate goal, the resolution of dream and reality into a new surreality.

The interior model

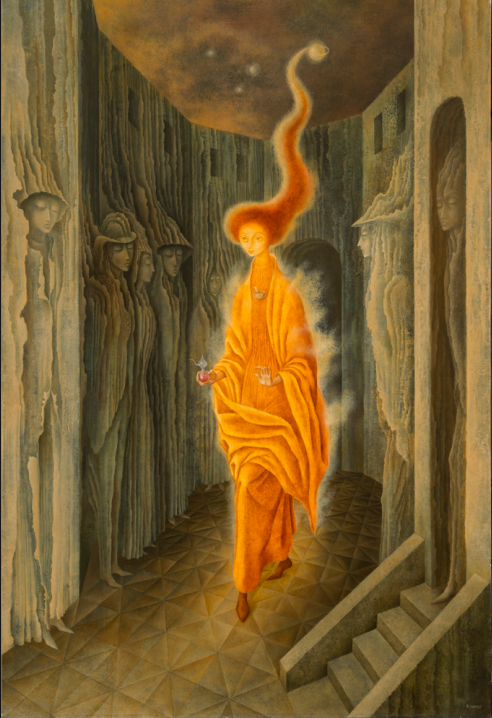

The Surrealists believed that the world of the imagination was the only proper subject for the arts, which must challenge what Breton called “the poverty of reality.” He claimed that the work of art must “refer to a purely interior model.” While this statement applies to all Surrealist artworks, regardless of productive technique, style, or subject, many Surrealist artists followed de Chirico’s example and created dreamlike imagery that appears to literally reveal the “interior model.”

Yves Tanguy’s meticulously painted depictions of imaginary landscapes stretching off to an infinitely distant horizon combine the naturalistic rendering of real space and light effects with suggestive abstract forms. Their naturalism invites the viewer’s imaginative entry into the world they make visible and presents the possibility that the world of the unconscious can be made real.

Realism as subversive

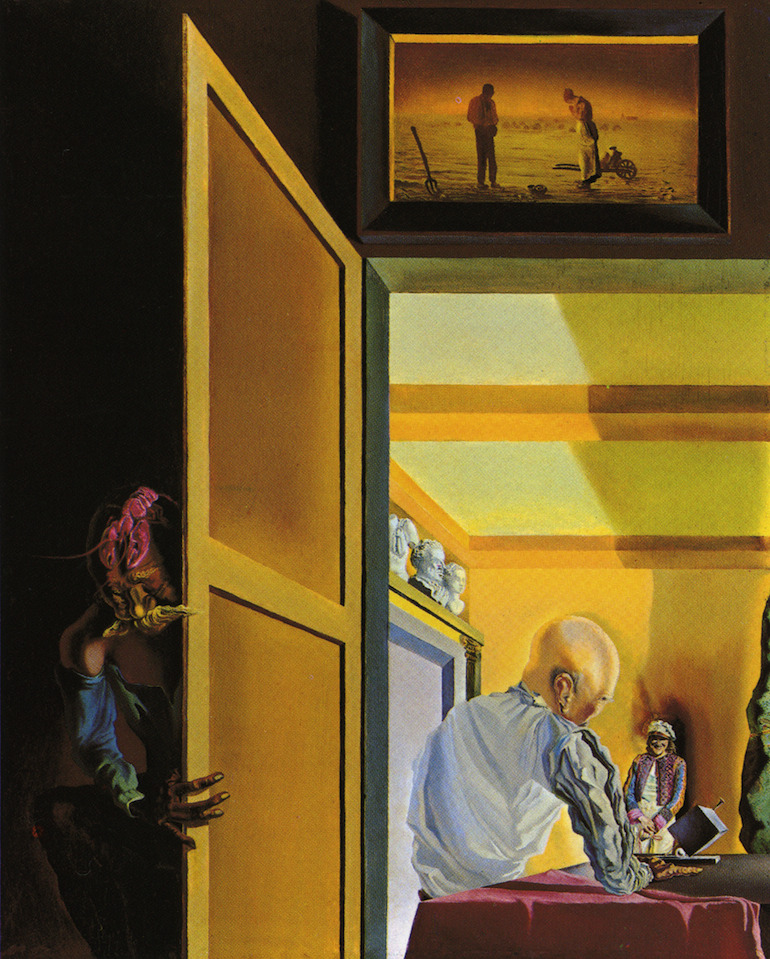

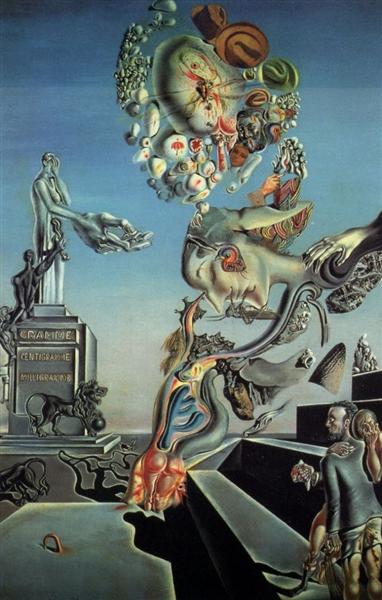

The realistic representation of the world of the unconscious reached its apogee in the paintings of Salvador Dalí, who adopted an extremely detailed realistic technique reminiscent of nineteenth-century academic painting. This was an explicit attempt to turn academic naturalism into a subversive technique.

The vivid realism of Dalí’s bizarre scenes seems to confirm that the world they represent is just as real as scenes encountered in ordinary waking life. In paintings such as The Lugubrious Game, Dalí minutely depicted his psychological obsessions, which were largely derived from Freud’s theories of infantile eroticism.

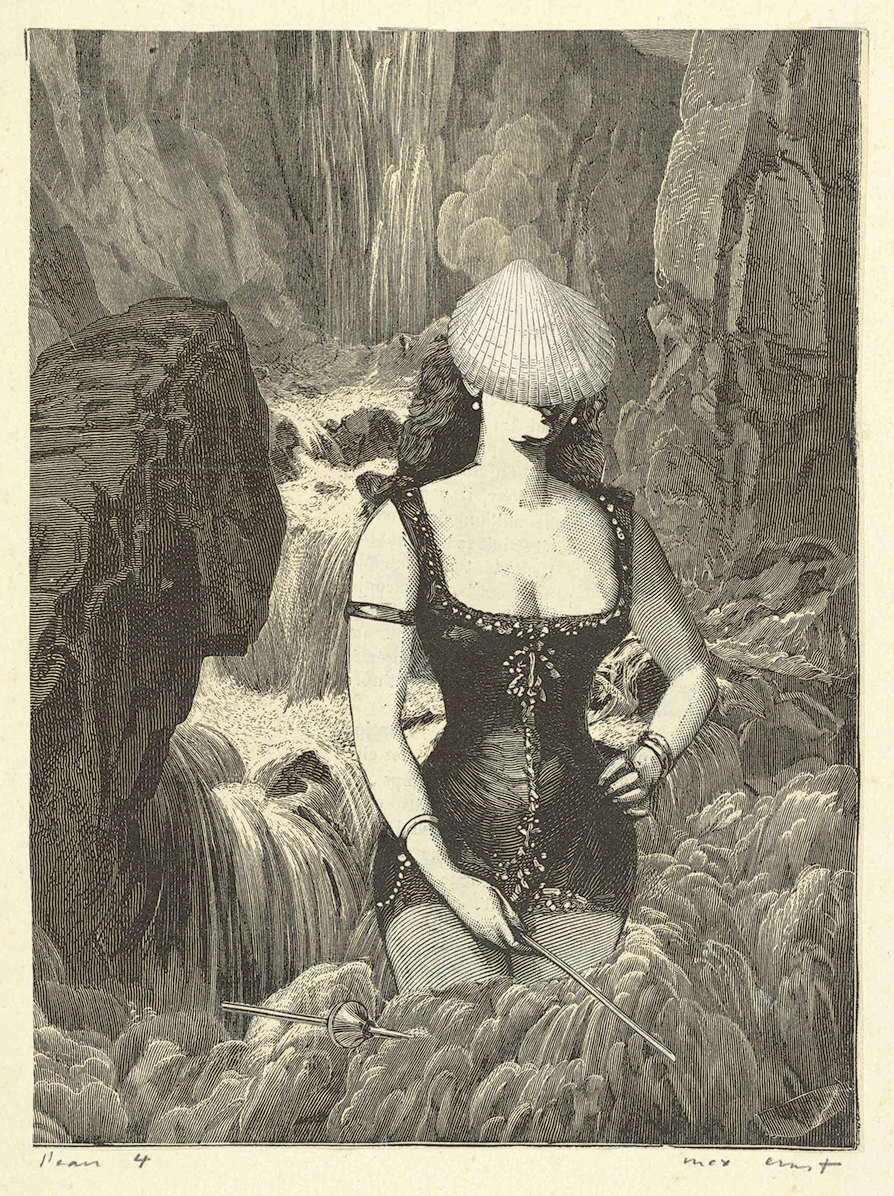

The artist’s profile floats horizontally in the center of the painting and generates a bizarre collection of objects, human figures, animals, and insects. Explicit and symbolic depictions of male and female genitalia abound, as do direct references to Freud’s theories of castration anxiety and anality. In this painting and many others Dalí portrays a universe in which the most apparently innocent objects, from a seashell to a man’s hat, acquire erotic significance.

Systematic confusion

His first published paranoiac painting, The Invisible Man, depicts a strange landscape with multiple figures and objects. Individual elements also create the figure of a large seated man. The back of a nude woman in the upper center of the image is one of his upper arms. His face appears in a collection of architectural elements, and his hair is also clouds. The longer you look at the painting, the more figures and parts of figures you will see. Paintings such as this were intended to make viewers aware that the “reality” they see is only one view. It is possible to make reality answer our desires simply by changing the way we look at things.Dalí invented a technical strategy for Surrealist art that he called “paranoia criticism.” In Dalí’s view unconscious erotic desires inevitably shape our vision of reality, and the Surrealist artist’s role is to demonstrate this in order to “systematize confusion,” overthrow rationality, and discredit what we think of as reality. Just as paranoiacs are convinced that seemingly unrelated objects and events are in fact intimately connected to their own obsessions, Dalí’s paranoiac paintings were intended to demonstrate how his imagination radically transforms objects to make them conform to his desires.

Philosophical conundrums

In contrast to Dalí’s often obscene and intentionally shocking imagery, René Magritte used realistic painting techniques to present philosophical conundrums about the nature of representation and its relation to reality and language. In The Human Condition, Magritte depicts the way a painting’s representation “replaces” reality, leading us to consider the many assumptions we make about realistic images and their relationship to what they represent.

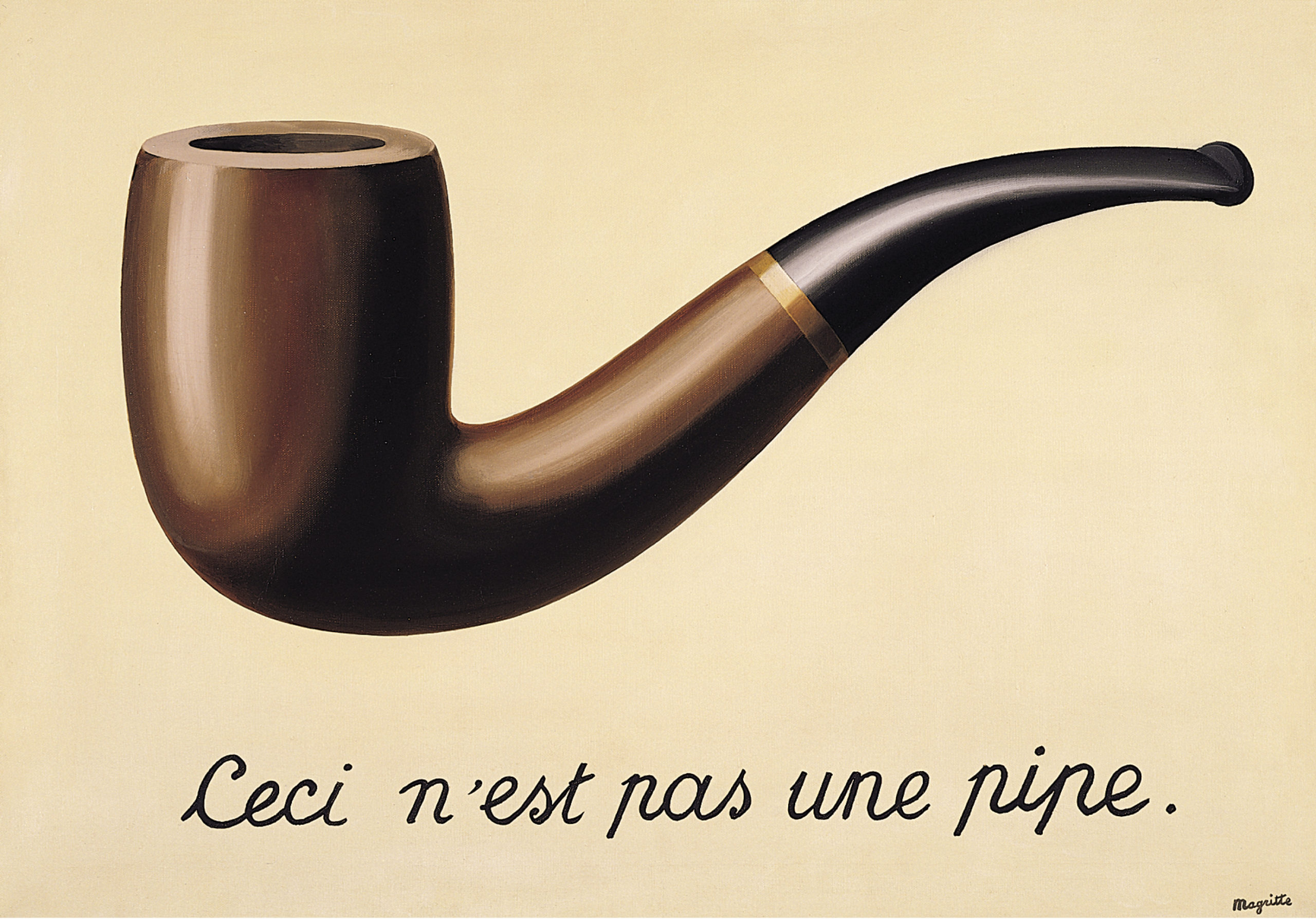

The Treachery of Images presents the disjunctions between the written phrase “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” (This is not a pipe) and the depiction of a pipe above it. Representation is not reality, although it may look like it; nor is language to be trusted as a source of truth about what is real. The painting of a pipe is not a pipe; but the word “pipe” is not a pipe either. By undermining comfortable assumptions about the human ability to understand reality through language and representation, Magritte’s works demonstrate that we make the world we think we know. Everything is, in the end, a question of representation (in words or images) in which we choose to believe, or not.

Salvador Dali, The Persistence of Memory: A Conversation

Dr. Steven Zucker and Sal Khan

To watch the video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6mp-fBJNQmU