Rita Zuba Prokopetz

Abstract

The electronic portfolio, or ePortfolio, is a learning site where students reflect and document their growth over time. As technology, the eportfolio is a vehicle of culture sharing among students in blended and online learning spaces. As pedagogy, educators can rely on its development process to enhance student experiences in an online learning community. Empirical observations spanning eight years in various communities of English as a second language learners have demonstrated the resiliency of students who opted to immerse in blended learning that included ePortfolio experiences. The learning derived from these observable experiences of language learners in a blended program provided the foundation for a subsequent study in a fully online master’s program where students developed their ePortfolio as a graduation requirement. The participatory observations of an ePortfolio subculture in communities of both language learners and also graduate students undergirded the notion that ePortfolios facilitate community building and enhance learning experiences in blended or fully online courses. Online ethnography, the method of observation used with both groups of students, enabled this researcher to capture behaviour patterns in the ePortfolio development process of her students in their learning communities. This chapter provides an insight into the experiences of an educator who, for the past eight years, has implemented ePortfolio pedagogy to enhance the blended learning experiences of language learners. It also reports on the methodology and theoretical underpinnings in which the observations of communities of English language learners were grounded while creating their capstone ePortfolio projects in a blended program and of graduate students developing their projects in an online course.

Keywords: Electronic portfolios, ePortfolios, affect, cognition, conation, ecological constructivism, taxonomy, online community, blended language learning, online ethnography

Introduction

In the early 2010s, approximately 20 learners of English as a second language (ESL) were introduced to blended learning mediated by their first ePortfolio as an extra-curricular class activity (Zuba Prokopetz, 2018a). Since then, subsequent cohorts of ESL students of low- to high-intermediate language levels have participated in blended learning experiences while developing their ePortfolios as a capstone project. These ePortfolio projects are developed by the students at a convenient place and time during the final weeks of their program of studies. In a full-time five-month blended language learning (BLL) program, these reflective projects are part of the final speaking assessment where the instructor provides online support to her students two out of five days each week. As posited by Vaughan, Cleveland-Innes, and Garrison (2013), instructors in blended learning environments necessitate being “collaboratively present in designing, facilitating, and directing the educational experience” (p. 3) of their students. In this five-module comprehensive program of studies, students have the opportunity to learn the technology and become familiar with their online learning space before they are introduced to their final project.

My Practice Using ePortfolios: First Stage of Collecting Ethnographic Data

I was introduced to the ePortfolio pedagogy when I was completing my graduate program of studies at a distance in 2013. The experience encompassed a significant and yet gradual transformation of thinking. It compelled me to share the ePortfolio pedagogy with my students (English language learners and college educators) albeit in a bricks-and-mortar setting at the time. In doing so, I saw from the onset the alliance of technology, pedagogy, and reflection. These concepts, and others that emerged later, helped cement my views on how to become both an observer and participant in what Kolb (2015) described as experiential online learning.

When I began my doctoral program of studies in 2015, I already had a mental picture of:

- what I wanted to research (reflection and peer-feedback interaction during the capstone ePortfolio project development);

- where and with whom I was hoping to conduct my study (master’s level participants in a fully online post-secondary institution in western Canada);

- when the project timelines would align with my personal, professional, and academic course schedules (the fourth year of my program);

- how I would conduct my study (an online ethnography as an observer and a participant in a community of students developing their ePortfolios as an instance of Internet culture); and

- why I wanted to pursue studies of a specific manifestation of ePortfolio Internet culture with students in an online university (gain an insight into this culture-sharing group; describe and interpret their experiences in an online community; and make a contribution to the field).

As such, I leveraged on what I had to offer to my research study (experience with ePortfolios with three different groups of students who were language learners, college educators, and graduate students). A desire to learn about and contribute to the field of online learning and ePortfolio pedagogy fueled my pursuit of knowledge. I recognized that a deeper level of learning was unveiling itself in my engagement with thick descriptions (Geertz, 1973) of the storytelling of ePortfolio creators.

As technology, ePortfolios become the vehicle for culture sharing among students, thus fostering collaboration, facilitation, and instructional direction in an online community of language learners. As disruptive – groundbreaking and innovative – pedagogy, when embedded in the coursework in a scheduled timeframe, ePortfolios help not only trigger the development of reflection but also deepen blended learning experiences. As such, both the educator and the students undergo a gradual transformation in their thought processes during the creation of the product, curation of the artefacts, and interaction with the members of a learning community.

Those who advocate for ePortfolios seem to be positioning themselves psychologically and pedagogically in a learning and teaching environment that necessitates a modified curriculum to deepen learning, facilitate reflection, and promote collaboration and interaction in a “new imagined ecology” (Batson, 2015b, para. 4). Conscientious BLL service providers rely on impactful instructional practices that not only bring forth metacognitive awareness but also make learning visible. Studies conducted by the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) revealed the impact of capstone ePortfolios as a high-impact practice (Kuh, 2008; Watson et al., 2016).

ePortfolios as a Capstone Project

Literature presents the ePortfolio as an educational innovation that leads to new research findings, as a high-impact practice, and fosters new uses, as a capstone project of culminating experiences (AAC&U, 2008; Kuh, 2008). Educational capstone ePortfolio project development enables learners and educators to experience the critical competencies (Gardiner, 1994) required in the 21st century. In addition, this educational technology, as suggested by Greenberg (2006), provides the users with the ability to create, curate, publish, and share their media-rich collection of pages, which, as I have observed, both empowers and engages the learners. As a student, I was fortunate to have the opportunity to complete both my graduate (2011-2013) and also doctoral (2015-2019) program of studies entirely at a distance. In both programs, I relied on an ePortfolio to articulate my application of knowledge on a personal, academic, and professional level.

From Face-to-Face Paper-Based to Blended Electronic Approach

In the early 1990s, paper-based portfolios became a powerful tool for teachers in traditional classrooms to conduct evidence-based assessments. The portfolio concept, however, had long existed outside academia in fields such as arts, photography, and architecture, among others. When the World Wide Web (Web) made affordances for educational technology pedagogy, educators began to perceive a significant paradigm shift in teaching and learning. This shift was of significant weight and force (Siemens, 2006) and led to a change in mindset among those who chose to incorporate educational technology in their learning and teaching. The ePortfolio, and other technology-mediated learning and teaching tools, made it possible for educators to begin introducing a blended approach to their practice. Conscientious educators were able to recognize from the onset that the Web tool innovation was not meant to be a silver bullet or quick-fix solution to an existing ineffective course design (Bryant & Chittum, 2013; Watson, 2012). Not only was the shovel-ware method (adding to the online environment content previously used in a traditional format) synonymous with inadequate teaching but it also did not provide “efficient solutions for learning” (Hadjerrouit, 2008, p. 29) in an online environment. Therefore, learning to learn online became a prerequisite for those language service providers who were contemplating the use of BLL pedagogies in their practice.

Blended Language Learning: Second Stage of Collecting Ethnographic Data

In the early 2000s, although my language classes were entirely face-to-face, I began relying on Internet culture in attempts to innovate my practice and learn how to introduce some form of blended instruction to my ESL students. As a cautious educator, I saw a need to learn more about online pedagogy before introducing the concept in my classroom; engagement of my ESL students in their blended learning experiences was crucial. Therefore, my approach was to learn with, from, and about ePortfolio pedagogy as well as experience the challenges as a first-time ePortfolio creator. In consequence, I capacitated my full immersion in the process of learning about this online tool while helping my students learn with it (Zuba Prokopetz, 2018b, 2019a). My first attempt at implementing ePortfolios in my language classes was in 2013, and the technology we used for our class project was LiveBinders. The eBinders, as the students referred to them, contained tabs for each of the four skills areas (listening, speaking, reading, writing) – the listening and speaking tasks were capacitated by the VoiceThread educational tool. The reading and writing tasks were accomplished by learning from and with SlideShare resources (knowledge intake) and uploading artefacts (knowledge production) to the respective pages of the electronic binder. These projects were completed by the students individually and in collaboration with peers as an extra-curricular activity, since there were no computers or Internet connections in the classroom at the time. In subsequent groups, one class project per semester was created as a Weebly to house not only learning resources but also student artefacts and their reflection on them.

ePortfolio Application in a Blended Language Class

Since 2018, the ESL students in a blended program have created their ePortfolios both individually and in collaboration with peers. In this five-month blended program of studies, the ePortfolios are the final project and they include artefacts in the four language skills. The collection of pages contains student-selected artefacts, reflection on their learning journey, and a number of inspirational quotes. During the development of their projects, students express their appreciation for being introduced to the ePortfolio – both product and process. These ePortfolio creators welcome the enhanced language learning possibilities of ePortfolio development in terms of both layout and composition. They embrace their ePortfolio project as a venue where reflective thoughts and perceptions of learning experiences are shared freely. The students in the first four iterations of a blended ESL class (2018-2019) embraced the creativity, connectivity, communication, and interaction with one another afforded by their ePortfolio experiences. As I have observed, in blended learning episodes that include ePortfolio projects, the students feel empowered as they engage with their projects and one another while creating, reflecting, and publishing their work to date (Zuba Prokopetz, 2018a).

This sense of student agency is present when the students articulate their appreciation for the ongoing feedback which leads to an increased sense of self-direction on a personal, academic, and professional level. The students welcome their ePortfolio learning space where they insert audio files, include their selected artefacts (production of learning), and post reflective thoughts (reflection on learning). As a result, the students gradually become self-directed learners when they notice a shift in their language learning experiences – from the traditional instructor-peer face-to-face interactions to a more student-centric approach in a blended learning format. As the students use their ePortfolio as a technology-mediated learning tool to showcase their achievements, which is a challenge on its own, they engage in an ongoing process of thinking about their own learning. They also participate in peer-feedback interactions on their ePortfolio projects, thus building and strengthening their online community. These enhanced blended learning experiences mediated by ePortfolios help the students demonstrate computer literacy and the achievement of some of the competencies in listening, speaking, reading, writing. Most importantly, however, is the ability of the students to become autonomous learners. While participating in the development of their projects, the students engage in peer-feedback interactions, begin to apply time-management strategies, and learn to reflect on their learning to date.

Review of the Literature

Literature on ePortfolios is robust, and it encompasses their types, applications, and benefits as well as their relationship with assessment and evaluation (Buzzetto-More, 2010). The articles and research study publications cover the uses for ePortfolios in various fields of study in higher education among educational institutions around the globe. Colleges and universities in face-to-face, hybrid, and totally online settings have begun to rely on the application of ePortfolios to enhance learning, foster reflection, and strengthen community building (Zuba Prokopetz, 2019b). These ePortfolio projects are of particular relevance in blended learning because, as posited by Hartwick (2008), they become an extension of the face-to-face classroom.

ePortfolio Types and Audience

Butler (2006) identified the different audiences for the various types of ePortfolios as being teachers, lecturers, mentors, employers, and individuals themselves. The field of education emphasizes three types of portfolios, which are credential, learning, and showcase ePortfolios (Zeichner & Wray, 2001). With the emergence of ePortfolios in the field of education, a fourth type was identified, which is the process ePortfolios; this type of ePortfolio encompasses a variety of activities that facilitate the development of reflection of students (Barrett, 2010).

The field of education has been ahead of other fields in adopting ePortfolios and continues to grow and advance in its thinking about and the use of ePortfolios (Butler, 2006). In the United States, ePortfolios have become prominent in higher education, and are being used in more than half of the college campuses (Eynon & Gambino, 2017). In my ESL classes, students engage with both the product (technology) and process (reflection) in the development of their projects. Once they become familiar with the technology, they begin to create ePortfolios for various purposes – job application, promotion, or further studies.

The Shift in Teaching and Learning Paradigms

The ePortfolio landscape has seen a rise in the number of ePortfolio users since the wide adoption of the World Wide Web in the mid-1990s. As such, there has been a shift in teaching and learning paradigms that are partly underpinned by technology-enabled learning tools. In order to avoid a technology push, it is crucial that the perspective of both learners and educators be considered; therefore, a solid foundation in the preparation of student-teachers is necessary (Aalderink & Veugelers, 2006). In the creative arts field, for example, the complexity involved in the production of ePortfolios, initially unnoticed by both artists and teacher-artists, may only become apparent when problems arise during the various stages of their development (Aalderink & Veugelers, 2006). In the nursing profession, ePortfolios have become prominent, and are being used regularly. These ePortfolios provide nurses, students, and professionals, with a place to record their professional growth over time not only for themselves, but also for their employers, and peers (Green, Wyllie, & Jackson, 2014).

Regardless of the discipline or field of studies, ePortfolios have the capacity to provide educators and learners with a learning space where they can demonstrate the achievement of core competencies (skills, knowledge, and ability) required in their field of practice or program of studies. ePortfolios belong to the information and communication technologies (ICT), a suite of tools applied in the storage, management, communication, and dissemination of information. These tools can be used to enhance the quality of education (Kale, 2015), and to enable educators to gain an understanding of how students are learning in the 21st century (Finger & Jamieson-Proctor, 2009). In consequence, instruction and assessment can be based on the “creation and the selection of powerful approaches that use the affordances of ICT to assess students and provide a diverse range of evidence of the students’ learning journey” (Finger & Jamieson-Proctor, 2009, p. 78). Therefore, blended learning spaces necessitate pedagogically sound educational tools such as ePortfolios to facilitate learning and teaching experiences. As I have observed, language learners exceed course requirements to include in their projects artefacts that are both level appropriate and also aligned with the core competencies. This educational endeavour is underpinned by the three learning domains.

Affect, Cognition, and Conation

The process involved in these pedagogically sound and theoretically underpinned projects aligns with the cognitive, affective, and conative domains described by Huitt and Cain (2005):

- cognitive domain – what I am learning;

- affective domain – how I feel about what I am learning; and

- conative domain – why I am learning.

The process ePortfolios in the capstone projects espouses the essence of deep, meaningful, intentional, and purposeful learning (Table 1.1). When ePortfolio creators become aware of their own capabilities, they strive to go further and deeper in their project development. The students also develop a certain resiliency toward the difficulties they face with the product (technology) and process (reflection, articulation of learning to date). Moments of frustration are replaced with learning episodes of discernment, contentment, and fulfillment – emotions that undergird reflection. As I have been able to observe, reflection seems to appear when conditions of learning are such that they evoke our inner-most thoughts about our own learning – what happened in a course or assignment, how the learning was perceived, and why certain decisions were made. Once cognition (what), affect (how), and conation (why) begin to work in tandem, students are able to engage in meaningful learning and reflection; as such, they begin creating different products to demonstrate their learning. They begin to rely on self-motivation, curiosity, self-regulation, and personal passion in their attempts to include artistry as evidence of knowledge acquisition and application that has taken place over a period of time.

Table 1.1

Comparing Aspects of Three Domains with Critical Competencies

| Affective | Cognitive | Conative | Critical Competencies |

| Appreciation for diversity and tolerance for cultural differences (1.2) | The recall of major generalizations about particular cultures (1.32) | Defining one’s purpose and identifying human needs | Respect for people different from oneself |

| Finds enjoyment in interacting with different people

(2.3) |

The ability to interpret various types of social data

(2.20) |

Positive social interactions with family and friends | Interpersonal and team skills |

| Continuing desire to develop the ability to speak and write effectively

(3.1) |

Skill in writing, using an excellent organization of ideas and statements, and ability to tell a personal experience effectively

(5.10) |

Aspirations, visions, and dreams of one’s possible futures | Skill in oral and written communication |

| Development of self-regulation mechanisms to deal with demands

(4.2) |

Development of a plan of work or the proposal of a plan of operations

(5.20) |

Making choices, setting goals, and developing an action plan | Consciousness, personal responsibility, and dependability |

| Readiness to revise judgments and to change behaviour in the light of evidence (5.1) | The evaluation of the accuracy of a communication from evidence as per various criteria

(6.10) |

Self-evaluation using data collected in the monitoring process | Skill in critical thinking and in solving complex problems |

| Development of regulation of

ethical principles aligned with democratic ideals (5.2) |

The ability to indicate logical fallacies in arguments

(6.10) |

Engaging in daily self-renewal and monitoring thoughts, emotions, and behaviour | Ability to adapt to a principled, ethical fashion |

Note: Adapted from Bloom et al. (1956, pp. 76-189 and pp. 201-207), Huitt and Cain (2005, p. 14), Krathwohl, Bloom, and Masia (1964, pp. 176-185), and from Gardiner (1994, p. 22).

During the development of their ePortfolio projects, students undergo a process that includes cognition, affect, and conation which are in alignment with the critical competencies (Gardiner, 1994), as illustrated in Table 1. As educators, we need to be cognizant of the mental processes of our students (within the knowledge domain) in the preliminary stages of a course or a unit of learning within that course. In doing so, we enable students to identify their own mental, emotional, intellectual, and physical competencies, as they undergo various learning episodes. Once the students demonstrate sufficient knowledge to apply what they have learned (knowledge and application), the initial learning layers within the cognitive system become the focus. At this stage, the affective domain (knowledge utilization system) becomes responsible for not only what information is being noticed (peer-feedback on ePortfolio pages), but also how much of the information is going to be filtered in to enable the analysis and comprehension of this new information.

The challenge in including affect in our current teaching practices is that, as Krathwohl, Bloom, and Masia (1964) have observed, during the creation of the original taxonomy, the affective domain presented a much bigger classification problem than did the cognitive domain. In addition, at the time, without evidence of growth connected with the affect, a parallel could not be drawn to the extensive work already done in the evaluation of cognitive achievements. As a result of poorly defined affective objectives, assessors had difficulty in assigning grades to students in respect to their interests, attitude, or character development – an aspect which is visible in ePortfolio projects. The ePortfolio in a capstone project, a site for meaningful research in Internet spaces (Zuba Prokopetz, 2019b), may facilitate future studies on domain integration (affect and cognition) as related to ePortfolio development experiences of students in blended and online learning. The finished product houses not only student records (courses completed) but also attitudes and behaviours (interaction with peers) on the collection of pages.

ePortfolio Community

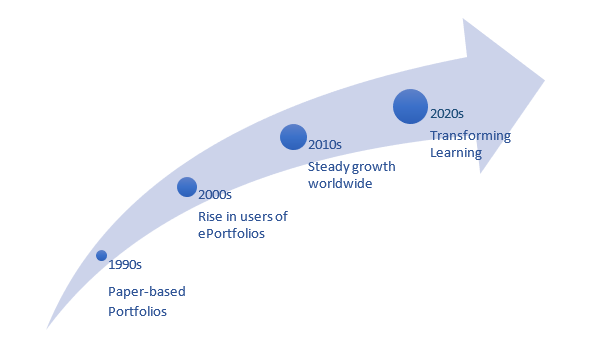

The process ePortfolios developed by students in a culture-sharing community of ePortfolio creators helps students align their learning with core competencies and gain a sense of ownership of their finished product. As technology and a reach beyond borders, the Internet is riddled with an intricate collection of communities. The communities of learners afforded by the ePortfolio are growing in both importance and numbers and have the potential to become a key aspect of the cultural mosaic of the collaboratory agency of worldwide connections, a concept brought forth by Wulf (1993). This collaboratory ePortfolio community seems to be an exemplar of what the world is already doing, as argued by Batson (2018): learning, creating, and working in imaginative spaces, where the members stay connected socially, extend networks, and engage in global thinking. In an online community of language learners, the ePortfolio is part of an ecosystem, a resilient and diverse network of systems that includes critical reflection, communication, interaction, and reflective feedback giving and receiving. In blended learning, the ePortfolio is positioning itself as a vehicle for reflection, curation of artefacts, and interaction with instructors and peers in the community. The ePortfolio projects are a manifestation of Internet culture, which in an educational context, consists of, as stated by Fullan (2013), communities that comprise many subcultures, and continue to grow in numbers of members; this growth contributes to the decades-old ePortfolio movement (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1

Trajectory of ePortfolios

The ePortfolio Movement

The ePortfolio movement has been gathering momentum for more than a decade now (Batson, 2015a; Cambridge, 2010; Eynon & Gambino, 2017; Ravet, 2005). In the early 2000s, there was a rise in the number of ePortfolio owners in Europe, Australia, the United States, and Canada; this global phenomenon accounted for hundreds of thousands of users at the time (Ravet, 2005, Introduction). In fact, the European Institute for E-Learning (EIfEL) predicted that by 2010, there would be millions of ePortfolio users among the countries which have adopted this ‘e’tool (Ravet, 2005, Abstract). Further research is required to determine the current scope of ePortfolio users worldwide and its application in blended learning.

In 2005, Ravet argued that the ePortfolio was becoming a necessary tool for the knowledge economy. He also suggested that in addition to linking individuals with similar competencies, interests, and abilities, as in a community of learners, the ePortfolio also enabled students to engage in life-long and life-wide learning during their feedback interactions. He further stated that, as an evolution and a transformation of past practice, the ePortfolio has reached beyond the initial field of education in Wales and England and is now a key component in some of the national learning policies of these two nations.

In 2017, Eynon and Gambino reported that ePortfolios had become prominent in higher education and were being used in more than half of the American college campuses. They added that although the number of students using ePortfolios in the United States each year had reached hundreds of thousands, educational technologists seemed to view the ePortfolio as something of the past. The authors emphasized the need for a broad understanding of the ePortfolio practice, further research, and additional student evidence of ePortfolio use.

Evolution of the ePortfolio Terrain

In the context of education, the portfolio was originally used mainly for assessing and documenting learning evidence. However, the terrain in the landscape of ePortfolios has evolved, and it now comprises organizations, associations, communities of practice, conferences, international journals, and university courses. ePortfolios have seen a steady growth worldwide, and they have become a sophisticated field of inquiry attracting the interest of scholars in various fields (Cambridge, 2010; Ravet, 2005).

ePortfolios became more prominent in American colleges and universities after the 2003 Campus Computing Project Survey was conducted. The analysis of the results showed that the time had arrived for educators to consider ePortfolios as more than just an interesting classroom innovation, and for scholars to recognize the need for research to catch up with practice (Cambridge, 2009). The survey resulted in the formation of the Inter/National Coalition for Electronic Portfolio Research (INCEPR) in 2003. Since then, a conscious effort has been placed on ePortfolio data collection (primarily on their impact on learning) and on building a dynamic group of ePortfolio users (Cambridge, 2009). To date, the ePortfolio community encompasses not only researchers and scholars but also classroom instructors and administrative staff, who have experienced in their institutions’ challenges and benefits during the preliminary implementation stages of this innovative technology (Eynon & Gambino, 2017; Light, Chen, & Ittelson, 2012). The ePortfolio has become one of the most promising indicators that we are now entering the age of a learning society (Ravet, 2005, Abstract). As a result, the ePortfolio community established an organization to promote ePortfolio projects, encourage research, and contribute to scholarship.

The Need for an ePortfolio Organization

As interest in ePortfolios increased among ePortfolio users in educational settings in the United States, the field needed a national organization to help with the promotion of ePortfolio learning to bring forth blended learning possibilities and transformational higher education to students. Consequently, the Association for Authentic, Experiential, and Evidence-Based Learning (AAEEBL) was established in 2009 (Batson, 2012; Batson, 2018), and it now holds conferences in various parts of North America every year. In addition, AAEEBL also established the International Journal of ePortfolio (IJeP) in 2011 to foster research on pedagogical practices related to the use of ePortfolios in education. These significant changes in the industry have contributed to a more vibrant community of ePortfolio users. The birth of the ePortfolio coalition (INCEPR) and the ePortfolio organization (AAEEBL) created opportunities for members to conduct research studies, present at conferences, and publish articles. INCEPR, for example, selects, on a yearly basis, ten institutions that work on their individual institution-wide projects as a three-year cohort to provide answers to questions related to ePortfolios. The researchers work on uncovering evidence-based data on the types of learning taking place in each of the ten institutions over a three-year period. AAEEBL, on the other hand, established in 2016 the AAEEBL ePortfolio Review (AePR) magazine, which has published seven issues to date.

In addition to the scholarship and conferences provided by the AAEEBL, the organization and its group of scholars are also engaged in research. A comprehensive survey was conducted among institutional members in five countries, and the results revealed more than sixty uses of ePortfolios in the campuses among the twenty institutions that completed the survey (Batson, 2010). The findings showed that the main purpose of ePortfolios in graduate programs (nursing, dentistry, medicine, and teacher education) is for documentation of a practicum component and for reflection on professional ethics. The survey further reported on the significant number of programs that were introducing an ePortfolio course where students integrated prior knowledge and skills from the various courses in their program.

My Research in ePortfolio Communities: Ethnographic Analysis

I began conceptualizing a research study with graduate students during my initial observations of language learners and college educators in their ePortfolio communities. I gained further insights into my study with students in a master’s program after experiencing BLL episodes in my ESL practice. The study on the perception of graduate students of their capstone ePortfolio project experiences was subsequently conducted in a fully online university in western Canada (Zuba Prokopetz, 2019b). In order to become more familiar with the culture, I volunteered and also interned in various iterations of a capstone ePortfolio course prior to beginning my online ethnography. During that time, I had an opportunity to observe simultaneously the development of ePortfolio projects by ESL and graduate students as well as college educators. The themes that emerged – technology, pedagogy, reflection, interaction – were present in my observations of all three groups of students.

In consequence, I began to see the interconnectedness of ePortfolio experiences with the four constructs that would anchor subsequent observations in the following three groups of students (Zuba Prokopetz, 2018a, 2019b, 2020):

- ESL students completing their capstone ePortfolio projects in the final module of BLL;

- College educators creating two pages of an ePortfolio as a project in a certificate program;

- Graduate students developing and presenting a collection of seven pages in their final course.

Online Ethnography: Analysis of the Role of the Researcher in an Ethnographic Study

These realizations necessitated that I see myself as more than an educator or observer who was participating in learning communities. My role evolved, and I became a participant-observer in fieldwork that “privileges the body as a site of knowing” (Conquergood, 1991, p. 180). As a human instrument (Lincoln & Guba, 1985), I was cognizant that I could not possibly remove myself from the experiences of those I was observing and be completely objective. Therefore, both my observations (with language learners) and subsequent study (with graduate students) necessitated that I be well informed of and comfortable with my own stance; my professional self-development mediated by my first ePortfolio experience helped me with that process (Zuba Prokopetz, 2018b). In addition, online ethnography, my choice of approach for my observations, guided me as I participated in communities (of ESL students and graduate students) in their natural setting – their online course site. As an observer, I attempted to be unobtrusively involved in the setting; as a participant, I aimed to interact with the students without imposing on their ordinary activities (Brewer, 2000). As a participant-observer, I relied on the online ethnographic approach to learn about the setting to enable me to acquire intimate familiarity with it (Brewer, 2000).

Beyond the Cognitive Domain: ePortfolio Phenomena Observed through the Lenses of Ecological Constructivism and the Affective Domain

When I began observing the experiences of ESL students, I used the lenses of a Constructivist / Interpretivist paradigm. My aim was to understand how students constructed their understanding of the world through their ePortfolio experiences. I relied on theoretical underpinnings which aligned with my positionality in each epistemological foundation – affective domain and ecological constructivism. By observing the experiences through the lenses of the Affective Domain of Bloom’s Taxonomy, I attempted to understand the choices the students made in their interactions, and their level of participation in their online community. By viewing the overall experiences also through the lens of Ecological Constructivism (Hoven & Palalas, 2016; Palalas, 2012, 2013, 2015), my goal was to gain a better understanding of the importance of the affordances of the environment during the project development process.

Ecological Constructivism

There are various forms of constructivism albeit not always distinguished in instructional design and blended instruction. Both individual and social constructivism are learning theories that share underlying assumptions. They also share an interpretive epistemological position that knowledge is acquired through engagement with content rather than by rote memorization. In individual constructivism, learners create knowledge through their interaction with the environment, whereas in social constructivism, students, who work in groups, gain a better understanding of concepts than students who work alone (Ormrod, 2009). Unsatisfied with finding a theory that would be a good fit for my study, I enabled what Gibson (1986) called vista, or another way of seeing, to cast a wider net to find a fitting theoretical underpinning for my design.

My ongoing observation of language learners in my blended language classes (2013-2019), and of graduate students in an online program of studies (2015-2019) took me beyond the Social Constructivist/Interpretivist paradigm. Further review of the literature introduced me to a more suitable theoretical approach – Ecological Constructivism (Palalas, 2012, 2013, 2015). This contemporary approach to a theory of learning highlights the mutual interaction of systems within and internal to the learners (Hoven & Palalas, 2016; Palalas, 2012, 2013, 2015) and aligns with my positionality on a personal, academic, and professional level. This theory of learning derives from “individual construal of affordances in the environment” and proposes to facilitate the description and explanation of “both the learning that is experienced while working alone and also while working with others” (Hoven & Palalas, 2016, p. 5). This approach to Constructivism has underpinned my observations. This ecological set of lenses helped me see and understand the formation of an ecosystem in an environment with networks of fluidly inter-linked contexts that facilitated the co-creation of knowledge among students (Hoven & Palalas, 2011, p. 706). Table 1.2 shows the alignment of the ePortfolio, a learning site in blended language classes, with the theoretical characteristics of Ecological Constructivism.

Table 1.2

Characteristics of Ecological Constructivism

| Characteristics | Ecological Constructivism | Electronic Portfolio |

| Affordances | -Inherent properties of our environment

-Subject to constant, and yet subtle change

|

-As a learning site: it makes affordances for the development of reflection (Gibson, 1986) |

| Learners | -Perceive, construe

-Act purposefully either alone or in collaboration

|

-As a vehicle for culture sharing: it enables creation both as a group experience and as an individual one |

| Learning | -Emergent from the perceived environment

-Afforded by novel experiences and technologies |

-As a technology-mediated site: it affords new vivencia or experiences (Fals Borda, 1997) and learner-learner, learner-teacher interaction |

| Knowing | -Co-created alone or in collaboration

-Perceived novel affordances enabled by interaction

|

-As an emerging pedagogy: it fosters peer interaction, makes affordances for collaboration, enables co-creation of knowledge |

| Environment | -Networks of fluidly inter-linked contexts

-Open, and permeable system – an ecosystem

|

-As a research area: it situates proponents in an “imagined ecology” (Batson, 2015b, para. 4). |

Note: Adapted from Hoven and Palalas (2011, p. 706).

Affordance, a term coined by Gibson (1986), is a key determinant of what an environment can offer, or afford, and is directly related to the “composition and layout of surfaces” (Gibson, 1986, p. 127). Affordances in an educational environment are inherent properties of that environment that learners may or may not perceive or utilize. These affordances, which are subject to constant, and subtle change, are facilitated by the ePortfolios during the feedback-giving and feedback-receiving interaction among the students. They are viewed by Gibson (1986) as a complementarity of the actors and their surroundings. Feedback interaction and reflection, as I have observed, are integral to learning, and ePortfolios are the catalyst for such reflective episodes (Henry, 2006).

In this learning environment, knowing is considered a novel affordance made possible by online engagement and interaction (Hoven & Palalas, 2011; Palalas, 2012, 2013, 2015). This new ecosystem, where students engage in reflective learning, peer-interaction, and modeling during feedback giving and receiving, requires a broad view of the ongoing activities among the students. There is a connection of technology with pedagogy, and theory with practice during the various stages of the ePortfolio development. As an observer of these learning episodes, I was able to experience among the students in the community the connection of the dimensions of the affective domain (emotions, feelings, attitudes, and beliefs) with, as posited by Tomei (2005), the effective application of technology for learning and teaching purposes.

Bloom’s Taxonomy of the Affective Domain

Six decades ago, Dr. Benjamin Samuel Bloom, an American educational psychologist, made substantial contributions to the field of education. Under his leadership, the Taxonomy of Learning Domains was created after interest in a theoretical framework was expressed at the 1948 American Psychological Association Convention in Boston (Bloom et al., 1956). The purpose of the framework was to provide assistance and facilitate communication among assessors. Discussions among scholars on the various concepts related to teaching, learning, curriculum, and assessment gave birth to the development of the theoretical framework under consideration. In the early 1960s, Bloom’s Taxonomy aligned well with the instructional objectives movement (Airasian, 1994; Mager, 1997; Marzano & Kendall, 2007), and it strongly influenced the original attempts to organize programmed instruction.

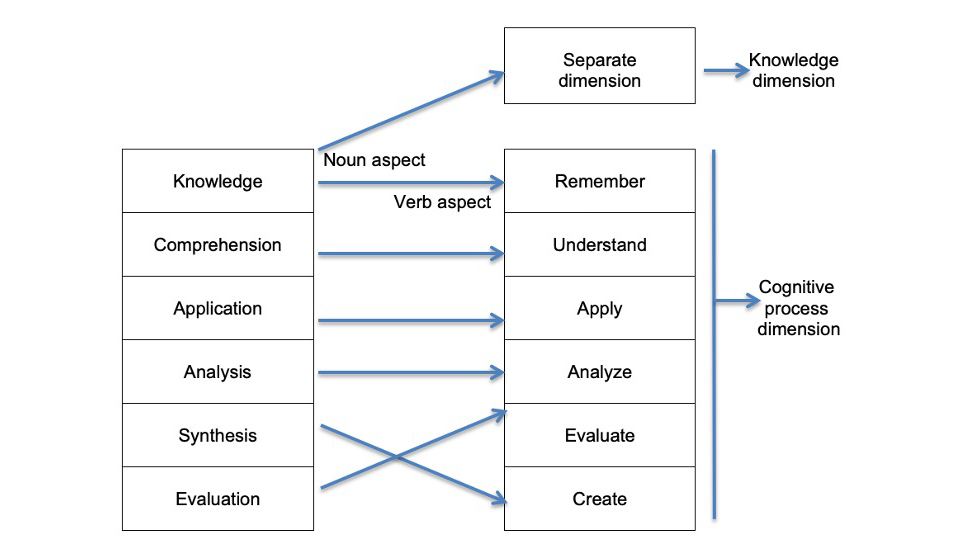

In early 2000s, D. R. Krathwohl, who had collaborated with Bloom in the original framework, provided a revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy to enable the knowledge dimension to be separate from the cognitive process dimension (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2

Original Framework and the Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy. Adapted from Anderson et al. (2001, p. 268).

In the 2000s, when the electronic version of the portfolio emerged as a reflective pedagogy, it underwent a similar trajectory; as a disruptive technology tool, it began positioning itself in a new educational movement (Batson, 2015a; Cambridge, 2010; Eynon & Gambino, 2017; Ravet, 2005). This time, however, the theoretical underpinnings necessitated going beyond the cognitive domains in order to align with the ways of thinking and learning in the 21st century.

My empirical observations of language learners showed evidence of how students participating in their ePortfolio projects attempted to establish a community. They seemed to rely on resources from their environment while engaging in a cultural sharing of learning. As I stepped back from my everyday observing, I noticed an overlapping of aspects of the taxonomy of the cognitive and affective domains during the interaction of the students with one another and their projects. As identified by Vaughan, Cleveland-Innes, and Garrison (2013), one of the trends in technology in higher education is the adoption of collaborative approaches in both learning and teaching. Group work promotes interaction and sharing, but purposeful collaboration provides an environment that validates the construction of knowledge (Vaughan, Cleveland-Innes, & Garrison, 2013) in blended spaces. As such, the implementation of an ePortfolio facilitates the learning of concepts (cognition) in addition to fostering the type of attitude (affect) required in post-secondary education.

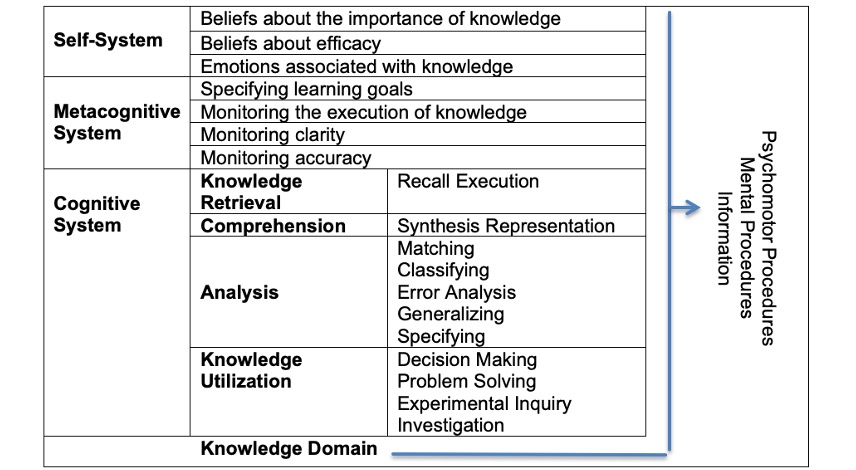

As a final project in a program of studies of language learners, college educators, and graduate students, capstone ePortfolio projects include elements of the cognitive system, self-system, and metacognitive system.

Figure 1.3

Matrix with Structural Elements of the New Taxonomy. Adapted from Marzano and Kendall (2007, p. 13).

The original and revised taxonomy necessitated yet another revision in order to embody new elements that would focus more on student learning and cognitive processes as opposed to student performance and assessments (Anderson et al., 2001; Marzano & Kendall, 2007). The new elements added to the matrix depicted in Figure 1.3 align with the theoretical positioning of innovative teaching of learning strategies, or a learning skills intervention (Hattie, Biggs, & Purdie, 1996). These learning strategies, which include various skills required in the digital world (e.g., time management, study skills, mnemonic skills) are classified into three categories: cognitive, metacognitive, and affective (Hattie, Biggs, & Purdie, 1996; Tuckman & Kennedy, 2011).

Comparable to the influence of the taxonomy on programming in the previous century, ePortfolios have become prominent enough in education to be the driving force behind collaborative efforts to organize 21st-century-compliant instruction, assessment, programming, and competency-based learning episodes. I continue to use the theoretical lens of the affective domain to help me better understand the attitudes and behaviours of the students as they develop their projects.

Implications to Blended Theory and Practice

As a ground-breaking and innovative technological tool and pedagogy, ePortfolios, as Chattam-Carpenter, Seawel, and Raschig (2010) suggested, have the potential to enable higher education professionals to conduct their classroom assessments, meet institution-wide standards, experience enhanced learning in their classroom, and help students increase their employability. In their capacity to facilitate and promote accountability in blended spaces, ePortfolios provide not only evidence of the teaching but also the quality of the learning that has occurred over a period of time. The Association of American Colleges and Universities affirmed capstone ePortfolios as a high-impact instructional practice based on the research showing that benefits to students go beyond their educational journey (Kuh, 2008; Watson et al., 2016). The educational value of ePortfolios resides in the process that students experience during their completion. These projects necessitate proper implementation to enable students to show evidence of their learning, instructors to connect with the students and their learning artefacts, and for students to collaborate, and engage in peer-feedback interaction (Eynon & Gambino, 2017; Kuh, 2008).

Conclusion

Traditional ways to learn and teach at both universities and colleges used to include a series of slides and faculty members in various disciplines who would lecture their student audience. In the 21st century, however, teaching and lecturing ought to be viewed differently, as Ramsden (1992) has suggested. As language instructors, we strive to teach ESL students rather than lecture them; this aspect is even more important in blended environments that necessitate our going “beyond capricious blending of face-to-face and online activities” (Vaughan, Cleveland-Innes, & Garrison, 2013, p. 3). The ePortfolio, as disruptive pedagogy, has been facilitating and enhancing learning in my ESL practice since 2013 – even before technology was available in the classroom. In addition, in my role as a researcher, the ePortfolio has made it possible for me to observe the behaviour and attitudes of graduate students as they developed their projects as a final program requirement. Therefore, the time has come for the ePortfolio to be viewed not as “a specific software package, but more a combination of process (a series of activities) and product (end result of the ePortfolio process)” (Barrett, 2010, What Is an ePortfolio? Section, para. 2). In blended learning spaces, ePortfolios have become a symbol of learning effectiveness, since they support co-construction of knowledge and are underpinned by theoretically sound pedagogy aligned with Bloom’s Taxonomy of the Affective Domain and Ecological Constructivism. This elegant learning tool places agency (learning through meaningful activities) in the hands of the students. During their blended learning experiences, ePortfolio projects provide students with a voice (through their personalized experiences) and choice (through their selection of artefacts). This disruptive pedagogy aligns with the guidelines established by the International Association for Blended Learning as they relate to structure, interaction, planning, and approach to instruction. As such, the implementation of ePortfolio projects in BLL needs to be well planned, well-integrated, and properly supported. In consequence, these projects not only enhance learning in spaces of the Internet but also strengthen online learning communities. The ePortfolio, as transformative pedagogy, empowers learners and strengthens online communities.

References

Aalderink, M. W., & Veugelers, M. H. C. H. (2006). ePortfolio and educational change in higher education in The Netherlands. In A. Jafari & C. Kaufman (Eds.), Handbook of research on eportfolio (pp. 558–566). Idea Group.

Airasian, P. W. (1994). Classroom assessment (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., Airasian, P.W., Cruikshank, K. A., Mayer, R. E., Pintrich, P. R., & Wittrock, M. C. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman.

Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2008). Quality, equity, democracy: key aspirations for liberal learning. Liberal Education, 104(1). https://www.aacu.org/liberaleducation

Barrett, H. C. (2010). Balancing the two faces of ePortfolios. Educação, Formação & Tecnologias, 3(1), 6-14. http://electronicportfolios.org/balance/

Batson, J. W. (2012). AAEEBL – Association for authentic, Experiential & evidence-based learning. hastac website. https://www.hastac.org/organizations/aaeebl-assoc-authentic-experiential-evidence-based-learning

Batson, T. (2010). Review of portfolios in higher education: A flowering inquiry and inventiveness in the trenches. Campus technology website. https://campustechnology.com/articles/2010/12/01/review-of-portfolios-in-higher-education.aspx

Batson, T. (2015a, February 2). Study shows steady growth in eportfolio use: What does that mean? https://drive.google.com/file/d/1ZVXXO2bmCoHXcM1ZYV20ejxiOw8kjJdC/view

Batson, T. (2015b, October 15). The significance of eportfolio in education. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1OTOgXcMZwL7J1lICUm9NF-X5xnCFrYsf/view

Batson, T. (2018). The eportfolio idea as guide star for higher education. The AAEEBL ePortfolio Review, 2(2), 9-11. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B5EyRIW5aG82dGtQTjJEcVk2R21JazZuRjFyb3BucVBMbUFZ/view

Bloom, B. S., Englehart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. Longman.

Brewer, J. (2000). Ethnography. Open University Press.

Bryant, L. H., & Chittum, J. R. (2013). ePortfolio effectiveness: A(n ill-fated) search for empirical support. International Journal of ePortfolio, 3(2), 189-198. http://www.theijep.com/pdf/ijep108.pdf

Butler, P. (2006). A review of the literature on portfolios and electronic portfolios. Massey University College of Education. https://akoaotearoa.ac.nz/download/ng/file/group-996/n2620-eportfolio-research-report.pdf

Buzzetto-More, N. (2010). Assessing the efficacy and effectiveness of an e-portfolio used for summative assessment. Interdisciplinary Journal of E-Learning and Learning Objects, 6, 61-85.

Cambridge, B. (2009). On transitions: Past and present. In D. Cambridge, B. Cambridge, & K. Yancey (Eds.), Electronic portfolios 2.0: Emergent research on implementation and impact (pp. xi – xvi). Stylus.

Cambridge, D. (2010). Eportfolios for lifelong learning and assessment. Jossey-Bass.

Chattam-Carpenter, A., Seawel, L., & Raschig, J. (2010). Avoiding the pitfalls: Current practices and recommendations for eportfolios in higher education. Educational Technology Systems, 38(4), 437-456.

Conquergood, D. (1991). Rethinking ethnography: Towards a critical cultural politics. Communication Monographs, 58, 179-194. http://www.csun.edu/~vcspc00g/301/RethinkingEthnog.pdf

Eynon, B., & Gambino, L. M. (2017). High-impact eportfolio practice: A catalyst for student, faculty, and institutional learning. Stylus.

Fals Borda, O. (1997). Participatory action research in Colombia: Some personal feelings. In R. McTaggart (Ed.), Participatory action research: International contexts and consequences, (pp. 107-120). State University of New York Press.

Finger, G., & Jamieson-Proctor, R. (2009). Assessment issues and new technologies: ePortfolio possibilities. In C. Wyatt-Smith & J. J. Cummings (Eds.), Educational assessment in the 21st century (pp. 63-81)

Fullan, M. (2013). Stratosphere: Integrating technology, pedagogy, and change knowledge. Pearson.

Gardiner, L. F. (1994). Redesigning higher education: Producing dramatic gains in student learning. Newark, NJ: New Jersey Institute for Collegiate Teaching and Learning.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures. Basic Books.

Gibson, J.J. (1986). The ecological approach to visual perception. Lawrence Erlbaum.

Green, J., Wyllie, A., & Jackson, D. (2014). Electronic portfolios in nursing education: A review of the literature. Nurse Education in Practice, 14, 4-8. https://www.nurseeducationinpractice.com/article/S1471-5953(13)00170-4/pdf

Greenberg, G. (2006). Can we talk? Electronic portfolios as collaborative learning spaces. In A. Jafari & C. Kaufman (Eds.), Handbook of research on eportfolios (pp. 558–566). Idea Group.

Hadjerrouit, S. (2008). Towards a blended learning model for teaching and learning computer programming: A case study. Informatics in Education, 7(2), 181-210.

Hartwick, P. L. (2018). Exploring the affordances of online learning environments: 3DVLEs and ePortfolios in Second Language Learning and Teaching [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Carleton University.

Hattie, J., Biggs, J., & Purdie, N. (1996). Effects of learning skills interventions on student learning: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 66, 692-715.

Henry, R. J. (2006). ePortfolio thinking: A provost perspective. In A. Jafari & C. Kaufman (Eds.), Handbook of research on eportfolios (pp. 54–61). Idea Group.

Hoven, D., & Palalas, A. (2016). Ecological Constructivism as a new learning theory for MALL: An open system of beliefs, observations and informed explanations. In A. Palalas & M. Ally (Eds.) The international handbook of mobile-assisted language learning (pp. 113-137). China Central Radio & TV University Press Co., Ltd. http://www.academia.edu/27892480/The_International_Handbook_of_Mobile-Assisted_Language_Learning

Hoven, D., & Palalas, A. (2011). (Re)conceptualizing design approaches for mobile language learning. CALICO Journal, 28(3), 699-720.

Huitt, W. G., & Cain, S. (2005). An overview of the conative domain. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta State University. http://www.edpsycinteractive.org/brilstar/chapters/conative.pdf

Inter/National Coalition for Electronic Portfolio Research (2003). incepr website. http://incepr.org/

Kale, P. (2015). Can ICT replace the teacher in the classroom? International Journal of Educational Research Studies, 1(4), 302-307

Krathwohl, D. R., Bloom, B. S., & Masia, B. B. (1964). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals, Handbook II: Affective domain. Longman Group.

Kuh, G. D. (2008). High-impact educational practices: What they are, who has access to them, and why they matter. Association of American Colleges and Universities. http://provost.tufts.edu/celt/files/High-Impact-Ed-Practices1.pdf

Light, T. P., Chen, H. L., & Ittelson, J. C. (2012). Documenting learning with eportfolios: A guide for college instructors. Jossey-Bass.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage.

Mager, R. F. (1997). Preparing instructional objective: A critical tool in the development of effective instruction (3rd ed.). The Centre for Effective Performance.

Marzano, R. J., & Kendall, J. S. (2007). The new taxonomy of educational objectives (2nd ed.). Corwin Press.

Ormrod, J. E. (2009). Essentials of educational psychology. Pearson.

Palalas, A. (2012). Design guidelines for a Mobile-Enabled Language Learning system supporting the development of ESP listening skills (Doctoral dissertation, Athabasca University). Athabasca University, Athabasca, Alberta, Canada.

Palalas, A. (2013). Blended mobile learning: Expanding learning spaces with mobile technologies. In A. Tsinakos & M. Ally (Eds.), Global mobile learning implementations and trends (pp. 86–104). China Central Radio & TV University Press.

Palalas, A. (2015). The ecological perspective on the ‘anytime anyplace’of Mobile-Assisted Language Learning. In E. Gajek (Ed.), Technologie mobilne w kształceniu językowym, pp. 29-48.

Ramsden, P. (1992). Learning to teach in higher education. Routledge.

Ravet, S. (2005). ePortfolio for a learning society. EIfEL. http://www.eife-l.org/activities/projects/epicc/final_report/WP7/EPICC7_7_Paper%20Brussells%20S%20Ravet.pdf

Siemens, G. (2006). Knowing knowledge. https://archive.org/details/KnowingKnowledge

Tomei, L. A. (2005). Taxonomy for the technology domain. IGI Global.

Tuckman, B. W., & Kennedy, G. J. (2011). Learning, instruction, and cognition. The Journal of Experimental Education, 79, 478-504. doi:10.1080/00220973.512318.

Vaughan, N. D., Cleveland-Innes, M., & Garrison, D. R. (2013). Teaching in blended learning environments: Creating and sustaining communities of inquiry. Athabasca University Press.

Watson, C. E., Kuh, G. D., Rhodes, T., Light, T. P., & Chen, H. L. (2016). Editorial: eportfolios: The eleventh high-impact practice. International Journal of ePortfolio, 6(2), 65-69.

Watson, J. (2012). Soft teaching with silver bullets: Digital natives, learning styles, and the truth about best practices. Proceedings of the 4th Annual Conference on Higher Education Pedagogy, USA, 175-176. https://chep.cider.vt.edu/content/dam/chep_cider_vt_edu/2012ConferenceProceedings.pdf

Wulf, W. A. (1993). The collaboratory opportunity. Science, 261(5123), 854-855.

Zeichner, K., & Wray, S. (2001). The teaching portfolio in US teacher education programs: What we know and what we need to know. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(5), 613-621.

Zuba Prokopetz, R. (2020). Student engagement and reflective learning mediated by ePortfolios: Observations of an ESL instructor. The AAEEBL ePortfolio Review 4(1), 13-18. https://aaeebl.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/AePR-v4n1.pdf

Zuba Prokopetz, R. (2019a). Uniqueness of ePortfolios: Reflections of a Creator, Curator, and User. The AAEEBL ePortfolio Review, 3(1), 17-23. https://aaeeblorg.files.wordpress.com/2019/06/aepr-v3n1.pdf

Zuba Prokopetz, R. (2019b). Capstone electronic portfolios of master’s students: An online ethnography [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Athabasca University. http://hdl.handle.net/10791/300

Zuba Prokopetz, R. (2018a). Electronic portfolios: Enhancing language learning. The AAEEBL ePortfolio Review, 2(3), 51-54. https://aaeeblorg.files.wordpress.com/2018/11/aepr-v2n3.pdf

Zuba Prokopetz, R. (2018b). Professional self-development mediated by eportfolio: Reflections of an ESL practitioner. TESL Canada Journal, 35(2), 156-165. https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v35i2.1295