Sangeeth Ramalingam; Haida Umiera Hashim; and Melor Md Yunus

Abstract

The impacts of Industrial Revolution 4.0 on the Malaysian education sector, most importantly in higher learning institutions, allowed more integration of technology and innovation in ESL education. Technology integration in teaching and learning has also been emphasized in Malaysian Education Blueprint 2015-2025, introduced by the Ministry of Education 2015, as it allows more personalized learning experiences for the learners. The incorporation of technology and innovation in second language instruction introduced various interactive and engaging teaching and learning methods; one of the most common approaches is blended language learning. Many Malaysian public and private institutions have integrated online instruction into conventional instruction in ESL classrooms. Different forms of blended learning practices are employed by the institutions such as MOOCs, Moodle, LMS, and other web-based technologies for the purpose of effective pedagogy. This chapter reviews the literature from various databases on the trends of blended learning implementation at Malaysian higher learning institutions. Subsequently, the authors explore the traditional pedagogical practices in second language teaching and learning as well as the modern pedagogical approaches in blended language learning. The roles of educators and students in blended language learning classrooms are also discussed. In the final part of this chapter, the authors highlight the challenges of blended learning implementation in Malaysian tertiary institutions and discuss the possible solutions to overcome the challenges.

Keywords: blended language learning, Malaysian tertiary education, pedagogical practices, challenges, possible solutions

A Brief Overview of Higher Education in Malaysia

Industrial Revolution 4.0 (IR4.0) is one of the buzzwords which has disrupted many phases of the life of human beings. IR4.0 which is often associated with words such as internet of things, big data, robots, and artificial intelligence impacts many different industries in various developing nations including Malaysia. Similar to other developing countries, Malaysia also faces the issue of Industrial Revolution 4.0 which requires graduating students from higher learning institutions to not only acquire good subject knowledge but also relevant soft skills needed by the current industries (Maria et al., 2018). This indicated that Industry 4.0 demands graduates who have higher qualifications and adequate 21st century skills to work in the organizations of this industry 4.0 era. Thus, the role and responsibility of Malaysian higher education institutions is very crucial in preparing graduates to be well equipped with relevant qualifications to work in current industries. Education 4.0 is a new term that emerged in line with this revolution.

Education 4.0 is a popular discussion topic as it has unavoidably influenced many sectors including education (Maria et al., 2018). The impacts of IR4.0 on the education sector, most importantly in higher learning institutions, facilitated the integration of technology and innovation in second language pedagogy. Teaching and learning processes have undergone changes with the integration of technology. Education 1.0 is focused more on face-to-face instruction whereby the instructor acts as a source of knowledge and the learners are the knowledge receivers (Gerstein, 2014). Instructivism, the method employed for Education 1.0, resulted in less interaction between the instructors and the learners. Education 2.0 was introduced in line with the emergence of Web 2.0 (Yamamoto & Karaman, 2011). It was used as a progressive method whereby the transmission of knowledge occurs not only between educator to learners but also learner to learner. The third revolution Education 3.0 emphasized the integration of technology for the purpose of knowledge dissemination. Education 4.0 is expected to produce students with good innovation abilities. It is believed that this education management will assist the learners to apply the latest technologies in their learning process (Maria et al., 2018).

Malaysian higher education aims to build a system that is well recognized at the global level; as such, it places emphasis on Education 4.0. Similar to the other developing countries, Malaysia is also ready to face the challenges of Education 4.0. Therefore, Malaysia Education Blueprint 2015-2025 (MEB) was developed by the Ministry of Higher Education (Ministry of Education Malaysia, 2015). This program was introduced to ensure the quality of the Malaysian higher education system to be in line with the global trend.

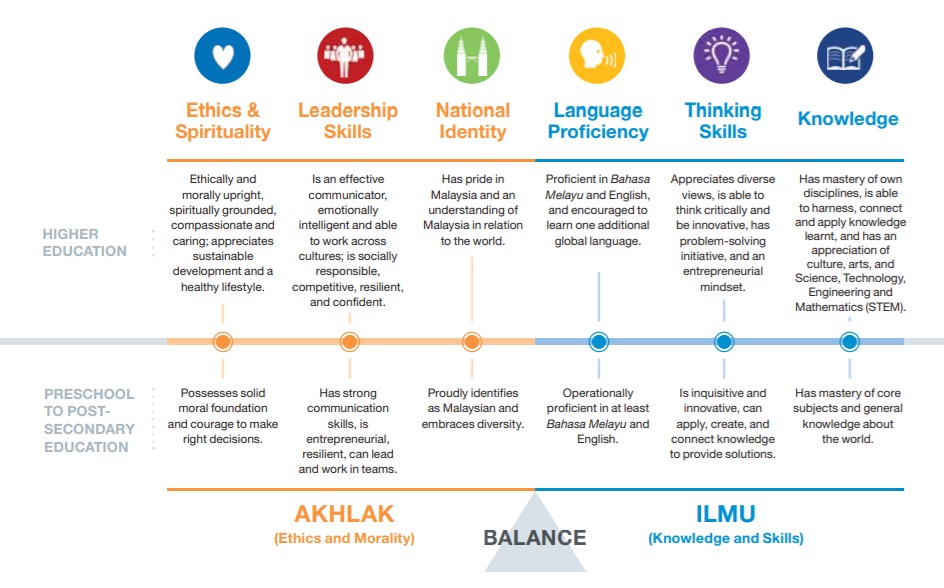

Figure 4.1

Emphasis of Malaysian Education Blueprint 2015-2025

Figure 4.1 demonstrates the emphasis of the Malaysian Education Blueprint. Two main emphases of the above blueprint are ethics and knowledge. There are three sub-components that are related to ethics, namely ethics and spirituality, leadership skills, and national identity. Ethics is related to the students’ morality and behavior. The second sub-component, leadership skill is related to the students’ ability to lead a group, communicate well, and socialize with others. National identity is the third sub-component where the students are supposed to understand the relationship between the country and the other nations.

The second emphasis of the Malaysian Education Blueprint 2015-2025 is on knowledge and skills. The three sub-components which are related to knowledge and skills are language proficiency, thinking skill, and knowledge itself. Language proficiency refers to learning and acquiring the national language of the country and English. Students are expected to master the English language as most of the resources are written in English and it is also the language used to communicate in an international context. Besides, students are also expected by Malaysian Higher Education to possess the ability to think critically in solving problems. The last sub-component – knowledge – refers to the students’ skill in understanding their field of study and application of practical skills in the real-world context.

Redesigning the higher education system in Malaysia involves different programs such as CEO@faculty, 2u2i, and Massive Open Online Courses or MOOC (Maria et al., 2018). CEO@faculty involves CEO from local and international contexts to conduct seminars or workshops in higher learning institutions. This is to enable both staff and students of the tertiary institutions to obtain significant guidance and information pertaining to the current issues and trends of industry fields. 2u2i is a program related to industrial training. This program enables students to gain exposure to the experiences of working in industries. Since redesigning a higher education system involves technologies, MOOC has been employed in tertiary institutions. MOOCs have enabled the students and educators to gather and share the resources required for the learning process. The Ministry of Higher Education of Malaysia has also recommended MOOCs as a tool for future learning processes.

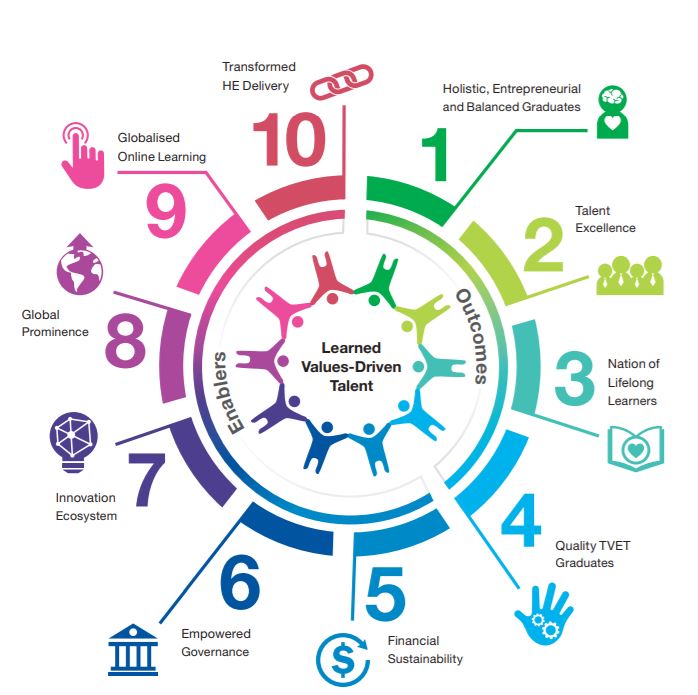

As for the purpose of improving the quality of higher education in Malaysia, the Ministry of Higher Education has outlined 10 shifts based on the Malaysian Education Blueprint 2015-2025 (Figure 4.2). The first four shifts emphasized the outcome while the remaining six shifts focused on the enablers of the higher education system. The 10 shifts are believed to be useful for the purpose of redesigning the Malaysian higher education system to face the needs and challenges of Education 4.0.

Figure 4.2

10 Shifts in Malaysian Education Blueprint 2015-2025 (Higher Education)

Technology integration in teaching and learning is emphasized in Malaysian Education Blueprint 2015- 2025 as it allows more personalized learning experiences for the learners. The incorporation of technology and innovation in second language instruction introduced various interactive and engaging teaching and learning approaches such as an environment that blended face-to-face and online learning called blended language learning (BLL). This chapter reviews the recent literature on blended language learning in terms of its implementation, challenges, and possibilities.

Trends of Blended Learning Implementation of Malaysian Higher Learning Institutions

The urgency for Information, Communication, and Technology (ICT) has made many Malaysian tertiary institutions, especially public universities, employ technologies in the process of teaching and learning. Many curriculum designers of tertiary institutions showed great enthusiasm towards the implementation of technologies in teaching and learning (Singh & Kaurt, 2017). Therefore, various online learning materials were developed for the purpose of teaching and learning both inside and outside the classroom. Singh and Kaurt (2017) stated that Malaysia ranked as the seventh-highest place (67%) for internet penetration level in Asia. This indicated the appropriateness of Malaysia to conduct online learning classes to improve the quality of the content and to enhance the teaching and learning processes.

The integration of technology in the curriculum introduced various trends and patterns in the learning process. More modern and new concepts in learning were introduced (Maarop & Embi, 2016). Technology has transformed teaching and learning from conventional classrooms to e-learning or digital learning. In many cases, web-based online programs were employed to deliver the content of the traditional classroom through online forums, videos, quizzes, video streaming, and so on (Azhari & Ming, 2015; Salleh et al., 2020). Online learning or web-based learning is not new in Malaysia as some higher learning institutions have initiated to apply online learning in 1990s. Due to poor student admission, tertiary institutions started to employ web-based learning due to its cost-effectiveness (Abd Rashid, 2016). Among the institutions which initially conducted web-based learning were Open University Malaysia, University Tun Abdul Razak, and two other public universities (University of Malaya and University Putra Malaysia).

Tertiary institutions were able to integrate online learning into the education system due to the fast and quick evolution of technologies. Since 1997, University of Technology Malaysia (UTM) has incorporated e-learning into their education system which enabled the educators to upload all the teaching and learning materials, such as the instructional notes, class schedules, course outline via online. University Tun Abdul Razak began to integrate web-based learning in their system in 1998 followed by the other tertiary institutions (Azhari & Ming, 2015). Reviewing empirical papers from the databases such as Scopus and Google Scholar revealed that online learning provides many benefits such as flexibility, cost-effectiveness, and greater accessibilities, leading to increased student satisfaction and motivation (Azhari & Ming, 2015; Hamidon, 2018; Salleh et al., 2020; Yusoff et al., 2020).

Ministry of Malaysian Higher Education’s aim, which in line with Education Blueprint 2015-2025, is to introduce ICT to simplify the process of teaching and learning as well as to enhance the pedagogies by providing the acknowledgment of the significance of ICT (Ministry of Education Malaysia, 2015). Another important objective stated in the Malaysian Education Blueprint 2015-2025 is to produce graduates who have a balanced quality of skills and to keep abreast with other nations globally (Shamsuddin & Kaur, 2020). The call from the Malaysian Higher Education Ministry was responded to by most of the tertiary institutions by making a pedagogical transformation from conventional face-to-face instruction to a blended learning approach to deliver the curriculum to the learners.

Blended learning pedagogy has been implemented in Malaysia since the beginning of the year 2000. Combination of face-to-face instruction and web-based learning benefits both the educators and the students in higher learning institutions. Independent learning, an increase in students’ interest, and engagement are among the advantages of blended learning (Apandi & Raman, 2020; Hani Salim, Ping Yein Lee, Sazlina Shariff Ghazali, Siew Mooi Ching, Hanifatiyah Ali, et al., 2018).

Generally, blended learning can be categorized into a few types or forms. While there is a large body of literature on forms of blended learning, most of the explanations are quite similar. Madarina et al. (2020) who completed research on improving written communication skills using blended learning, elucidated about three key technologies used for blended learning, namely learning management system tools (LMS), social media, and synchronized tools. LMS can be referred to as the tools which are related to web-based technologies. Facebook, Whatsapp, Telegram, Twitter, and Skype fall under the category of social media. Lastly, synchronized tools are the ones that can be accessed openly without restrictions, such as Zoho apps, Google apps, and Dropbox.

The most common pedagogical tools used by Malaysian public and private tertiary institutions to share the instructional materials with the students are LMS’s and MOOCs. Numerous courses have been converted into MOOCs (Bokolo et al., 2019; Sidek et al., 2020). For instance, Sultan Idris Education University converted into MOOC’s the following three courses: Computer Architecture and Organization, Blog and Website Development, and Special Needs Children; as a result, these three courses were observed to attract more students from around the globe (Sidek et al., 2020).

Apart from the MOOC courses, Sultan Idris Education University also implemented its own blended learning platform which is called MyGuru. Another Malaysian tertiary institution that has developed a similar online platform, called Goals, is the Islamic Science University of Malaysia (Yan Ju & Yan Mei, 2018). Both MyGuru and Goals are used by the educators to share course outlines, slides, handouts, learning materials, videos, and so on with the learners. Educators of the Islamic Science University of Malaysia are trained on how to fully utilize their online platform for their teaching activities (Yan Ju & Yan Mei, 2018). It is crucial for all these tertiary institutions to conduct training sessions for the educators to enable them to grasp the idea of applying and maximizing the tools for their teaching and learning activities.

One of the Malaysian public universities which greatly supported the employment of technologies in teaching and learning strategies is the University of Science Malaysia. Online learning in this university began in 2002 when a learning management system was introduced (Singh & Kaurt, 2017). E-learning at this university was conducted using online forums and video conferencing in an LMS system. University of Science Malaysia shifted to Moodle after considering few other open-source options in 2004. Starting from 2009, all the centers in this university have gone through restructuring in teaching and learning pedagogy whereby eLearn@USM intended to provide more meaningful learning experiences for the students (Singh & Kaurt, 2017). Various applications such as iRadio, iWeblets, and iTutorials were incorporated into the blended learning platform (eLearn@USM) to enhance the learning experiences among the students. Apart from the institutions mentioned earlier, there are many other public and private Malaysian tertiary institutions which are implementing various blended learning tools such as podcasts, videocasts, online forums, and virtual learning platforms to conduct educational processes that seamlessly blend learning in-class and online.

Traditional Pedagogical Approaches in Second Language Teaching and Learning

Before the emergence of technology, various approaches were employed in second language teaching and learning. ESL education has gone through many transformations and paradigm shifts. Different methods or techniques were used in the field of second language teaching and learning (Barrot, 2014). Grammar translation method was among the initial approaches which were used in the field of ESL teaching. This approach was employed for the purpose of language instruction, and it was conducted in the students’ first language (Krashen, 1982). Based on an analysis of language teaching approaches, Qing-xue and Jin-fang, (2007) emphasized that learners were quite passive, and the teachers seem to be authoritative in the grammar-translation approach.

Approaches in language teaching then shifted from grammar-translation to audiolingualism. Both grammar-translation and audiolingualism greatly rely on behavioristic ways of language learning and therefore they were heavily criticized by Chomsky (1968) for not being adequate. This contributes to the introduction of the cognitive view of language learning by Hymes (1970) whereby he established the concept of communicative competence for language learning and teaching. There were some changes in the ESL pedagogy particularly in terms of the methods after communicative language teaching was introduced. More techniques were introduced in ESL pedagogy, especially the bottom-up and the top-down skills (Hinkel, 2006). Even after communicative language teaching gained its popularity, it also has been criticized for several drawbacks. Kumaravadivelu (2006) argued that this approach is relatively inefficient as it is difficult to implement in India, South Korea, China, and Japan.

Thus, more transitions occurred in the field of second language teaching and learning. Task-based language teaching was introduced as an alternative approach. This approach integrated different methods such as collaborative learning and assisted the students to enhance their skills in a second language (Skehan, 1998). Nevertheless, task-based language teaching failed to include broader aspects of culture (Kumaravadivelu, 2006). As task-based language teaching has limitations in terms of the cultural aspect, many scholars (Corbett, 2003; Phipps & St Clair, 2008) have advocated for an intercultural approach which intended to help the students to communicate with learners from other cultures. The approaches which have been discussed earlier were the initial approaches employed in the ESL pedagogy. There were few other approaches that have been established after the intercultural approach due to ongoing constant evolution in the field of the second language.

Most of the initial approaches employed in second language teaching and learning were more teacher-centered with teachers “transferring” knowledge to passive learners and having the authority to choose the teaching techniques and forms of assessment. Ahmed (2013) explained that learners had no control over their own learning process in a teacher-centered classroom. Learners needed to fully rely on their teachers for their learning process. When the teachers maintain full control of the classroom, students will not be able to express themselves and therefore they feel less responsibility for their own learning process (Otukile-Mongwaketse, 2018). Various transformations and shifts in ESL pedagogy have gradually changed the teacher-centered classroom to the learner-centered classroom. Second language teaching and learning approaches have become more learner-centered with the help of ICT tools and platforms.

New Pedagogical Approaches in Blended Language Learning

Reviewed literature depicted that various blended learning pedagogical approaches and methods have been implemented in the ESL context at Malaysian higher learning institutions. English is considered a significant language due to the implication of globalization (Sasidharan, 2018). Thus, educators are deemed fully responsible for ensuring suitable methods are being employed in Malaysian ESL classrooms. This is to produce Malaysian graduates who are knowledgeable, skillful, and at the same time able to communicate effectively. The drastic changes in the pedagogical approaches in ESL classrooms are due to the developments in ICT that enable the educators of public and private tertiary institutions to integrate technology into their second language teaching process. It is very crucial for the educators to be in line with the era of technology and this included the change from the face-to-face classroom to non-face-to-face classroom (Harun & Hussin, 2018). Therefore, virtual communication became one of the significant skills particularly in this era of Industrial Revolution.

A considerable number of studies were conducted focusing on methods employed in ESL classrooms to teach and improve learners’ language skills and one of them is the use of social media (Annamalai, 2019; Mohd Zaki & Abdul Aziz, 2019) that can support blended learning. Some of the platforms employed in English language instruction include Facebook, Whatsapp, and Youtube. Both Annamalai, (2019) and Mohd Zaki and Abdul Aziz, (2019) have conducted studies on the use of social media in second language teaching at tertiary institutions and the findings revealed improvement in the students’ language skills. Social media blended learning tools also could be employed for students who have different learning styles such as visual, auditory, and kinesthetic, which was evidenced in a study of YouTube videos applied for various learning styles (Mohd Zaki & Abdul Aziz, 2019).

Apart from social media, other web-based tools, such as Moodle and Edmodo are also broadly used in ESL classrooms at Malaysian tertiary institutions (Annamalai, 2019; Sasidharan, 2018) to support English language face-to-face instruction. Other than web-based tools, smart mobile phones are used extensively among ESL learners and educators. Activities such as listening to podcasts, watching videos, and reading online books utilizing mobile phones have allowed the students to develop their 21st-century skills and evolve from pedagogy to heutagogy (Annamalai & Kumar, 2020). While heutagogical approaches promote learners to become more self-directed and be responsible for their own learning, educators should ensure that digital technologies are used “intentionally and selectively, guided by clearly defined learning objectives, and integrated into the curriculum by technologically adept educators who provide appropriate, ever-decreasing support and scaffolding as learners become more self-determined” (p. 151). In short, teachers need to be familiar with the suitable method to incorporate mobile tools into ESL teaching so that they can make these decisions. In addition, students need to be given the right guidance to co-create the content. Past literature discovered gamification, a non-gaming software as a common method in English language learning to facilitate face-to-face learning among the students and the educators. This non-gaming software which integrates gaming features employed in ESL education proved to be an excellent tool to enhance students’ language learning (Lim Jia Ying et al., 2019). The utilization of gamification in blended learning ESL classrooms emphasizes the cybergogy approach which encourages more learner engagement in an e-learning environment (Wang & Kang, 2006).

The novel pedagogical methods observed in blended language learning comprise heutagogy, peeragogy as well as cybergogy. Heutagogy encourages self-directness among the learners (Hase, & Kenyon, 2013). Peeragogy emphasizes co-creating or co-learning (Rheingold, 2014), whereas cybergogy promotes learner engagement in online learning (Wang & Kang, 2006). These new pedagogical approaches in ESL blended classrooms benefit the learners. The use of social media, mobile apps, and gamification assists the learners to boost their motivation in their English language learning (Annamalai & Kumar, 2020; Harun & Hussin, 2018; Lim Jia Ying et al., 2019). Students with low inspiration feel more motivated to improve their English as mobile applications and social media tools facilitate their whole learning process. Mobile learning, at the same time, helps the students to increase their communication with their peers and instructor; relying on mobile technology to mediate the learning experience across various spaces (Palalas, 2013). Annamalai and Kumar, (2020) posited that the use of smartphones in ESL classrooms enabled the learners to interact well with their other classmates and their instructors. Besides, mobile phones are considered as an appropriate device because it gives dynamic learning experiences to the students (Annamalai & Kumar, 2020). Among the other advantages of technological methods in blended learning are to enhance students’ enthusiasm and to increase willingness to participate (Annamalai, 2019; Lim Jia Ying et al., 2019). As we can see, lecture-based language instruction has been gradually transformed to learner-centered whereby the learners study at their own pace and are responsible for their own learning process.

Roles of Educators and Students in Blended Language Learning Classrooms

Blended language learning has become one of the strategies to provide convenience to both students and educators (Palalas, 2019). Especially today, in this context of pandemic, the practice of a blended language learning classroom is offering an advantage. To attain a successful blended language learning classroom, it is crucial to bear in mind that it takes two to tango – both educators and students are required to fulfill their roles and responsibilities. The following sections provide an insight into how both educators and students could play their part in making a blended language learning classroom a success.

Roles and Responsibilities of Educators

Educators play a big role in students’ learning processes and environments (Sukma et al., 2020). It is crucial for educators to note that technology is not meant to replace teachers, rather technology is used as a tool that enables teaching using innovative pedagogies and it also allows to save time and labor, if used appropriately. Nevertheless, the existence of blended language learning classrooms and technology does not restrict teachers to not make use of the traditional pedagogies. Instead, blended language learning classrooms allow teachers to use technology to enhance and enrich the learning experiences of the students (Asif et al., 2020) based on proven approaches. The combination of face-to-face methods with the integration of virtual classrooms does not only support teaching but also scaffolds the learning process.

Bath and Bourke (2017) in their study have mentioned four primary considerations in applying blended language learning models in language learning classrooms. The four primary steps of considerations for educators are planning, designing, and developing the blended learning elements, implementing, and finally reviewing and evaluating the design. Teachers must be thorough in the planning of the content, learning resources, learning activities, and assessments.

The very first thing to take note of in implementing a blended language learning classroom is educators’ readiness and savviness in using technology. Getting familiar with technology could be tricky and challenging for the educator, especially those who have no prior experience with technology-assisted teaching. Hence, instructors must be willing to experiment with new approaches to make use of technology. Variety is good in providing students with more interactive and fun blended learning classroom experiences. Educators thus have to be lifelong learners who invite change and progress. They can start with proven technologies they use outside of the classroom, such as WhatsApp and Telegram, and apply them gradually.

Blended language learning classrooms do not mean replacing face-to-face classrooms or instructors with technology (Rasheed et al., 2020). Teachers should select the digital content and tools intentionally to provide students with materials that are meaningful and can scaffold them with their language learning process (Palalas, 2019). In designing the BLL events, authenticity and real-world communicative activities should be included. The blended learning environment is the best chance for the students to have authentic life experiences in their learning process (Lapitan et al., 2021). A purposeful combination of in-person and digital content and delivery methods should enhance the learning experience and the understanding of the topic.

In addition to that, it is also crucial for educators to bear in mind to be realistic with the implementation of a blended language learning classroom. Educators should systematically plan for the success of the BLL classroom. They should take into consideration the students’ preparedness, as well as their convenience and time. Some educators might have the tendency to ignore the students’ restrictions and limitations, also the students’ tight schedules. Educators should bear in mind that students have other classes that they must commit to, hence educators should make sure that the implementation of a blended language learning classroom is not in a way pressuring students and making them feel stressed out. Providing ample time for the students to do the assessments and offering flexibility will make them enjoy the blended learning classroom better. In providing feedback, teachers need to consider providing immediate feedback to the students’ tasks. The feedback can be done via online tools in blended learning mode or during face-to-face discussion. It is crucial for teachers to provide feedback to promote learners’ growth. Feedback should come with empathy and encouragement to further motivate students in their learning process.

Educators need to always reflect on their own pedagogy, on whether the teaching sessions manage to give meaningful impact to the students and foster their learning. One size does not fit all and effective learning outcomes of each individual student are essential. BLL offers opportunities to cater to diverse students’ needs. Sari et al. (2018) concluded that blended learning is the environment that combines both positive sides of the traditional mode of teaching and learning with improved technology used to enhance and engage students’ motivation and involvement during the teaching and learning process.

Roles and Responsibilities of Learners

In a blended language learning classroom, learners also play a big role in making BLL a collective and individual success. Whilst teachers play their role in providing a meaningful learning environment to the students, students’ responsibility is to participate and engage in the learning sessions actively. A blended learning environment offers to the 21st-century student more collaborative experiences. Many students are well prepared and comfortable with the virtual learning environment as they find it convenient and intriguing to utilize new technologies and gadgets.

Learners must take the ownership of their learning as well as become a collaborator and communicator. They should be able to become a creator by exploring and creating various ways using both traditional and online activities. Learners must be willing to be more independent and practice self-paced learning while accomplishing the tasks in person and virtually. In the BLL environment, students are encouraged to get out of their comfort zone and get into the researcher role by thinking critically, developing their own ideas and questions to guide their learning. Isman and Dabai (2004) proposed in their study that the changing roles of students and educators influence classical education standards and pedagogy. According to their research findings, the roles and responsibilities of the students are to be disciplined and on-task in finishing the assessment or task provided by the teacher. Students also need to have the initiative to consult and seek guidance from their teacher through required access methods. They must take ownership of their own learning and reflect on their performance apart from the teacher’s feedback. Other than that, students need to interact with their teachers and peers in accomplishing the tasks and to overcome communication barriers. That can be achieved using novel pedagogical approaches mentioned above or relying on proven theories of learning, such as constructivism.

Constructivist techniques support learning and teaching, self-development, and self-evaluation (Isman, 1999). Constructivism focuses on the students and their active role in learning supported by technology. Accordingly, students need to make full use of the appropriate technology to interact collaboratively with their peers and teachers. They also carry the responsibilities of incorporating feedback provided by their teacher to develop and refine their knowledge, skills, and attitudes. In the constructivist BLL context, students are encouraged to take responsibility for their own learning, conduct their own research, and be more independent in answering questions and solving problems incorporating authentic assessment and real-life communicative tasks. That should promote lifelong learning and help students access and use information when formal BLL instruction is concluded.

Challenges of Blended Learning Implementation and Possible Solutions to Address Them

Some challenges and limitations are to be expected when implementing blended language learning in a formal classroom. One of the key ones is the lack of technical resources and facilities. In the Malaysian higher education context, almost all public and private universities and colleges are shifting to blended language learning solutions. The Malaysian Ministry of Higher Education has urged every university to introduce blended learning in their teaching and learning processes as a new approach (Yusoff, Yusoff, & Noh, 2017). However, one may question how efficient the practice and implementation without proper technical resources and appropriate facilities can be. There have been numerous cases when insufficient technology, support, and infrastructure stalled the BLL initiative for both educators and students, as evidenced in the study by Khan et al. (2012). In addition, De Jong et al. (2014) highlighted other major issues relevant to blended learning systems, namely insufficient cultural adaptation and limited technical know-how. Both students and teachers must be able to adopt the change in their teaching and learning style whilst their social interaction and communication should not be jeopardized at the expense of technology use.

There is room for improvement in the implementation of blended learning practice and it should start with addressing these issues. To promote a successful execution of BLL, higher education institutions should provide supports to develop adequate knowledge, skills, and training for teachers on using technology in the blended learning classroom (Osman & Hamzah, 2020) along with suitable resources and facilities.

Conclusion

In the Malaysian context, which emphasizes preparing learners for the Fourth Industrial Revolution or Industry 4.0, blended learning has now become the key to the reform of education. The Malaysian government, through the Ministry of Higher Education and the Ministry’s National Higher Education Strategic Plan (2011-2015), has successfully implemented the e-Learning agenda in the higher education institutions. Through the e-Learning National Policy in 2011, the ministry supported ubiquitous learning and ensured compliance of ICT in Malaysia’s higher education. As blended learning waves continue to take an even more prominent role in today’s higher education setting, understanding the issues and challenges the learners and teachers face has become paramount to the effectiveness of innovative blended learning (Muhammad et al., 2020). Most importantly, such understanding is crucial in assisting educators to plan and create better instructional designs with careful consideration of underlying pedagogy.

While there is no doubt that blended learning approaches have increasingly been implemented in higher education, it is essential to underpin this shift towards technology-based learning with robust learning theories. It is also important to gauge learners’ prior knowledge and competence to accommodate their access to online learning materials to motivate them to actively learn. Learners’ digital and information literacy and prior learning experience in digital learning have to be carefully evaluated. Their preferred approaches in learning should also be taken into consideration to ensure the effectiveness of the blended learning approach.

References

Abd Rashid, Z. (2016). Review of Web-Based Learning in TVET: History, Advantages and Disadvantages. International Journal of Vocational Education and Training Research, 2(2), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijvetr.20160202.11

Ahmed, A. K. (2013). Teacher-Centered Versus Learner-Centered Teaching Style. The Journal of Global Business Management, 9(1), 22–34.

Annamalai, N. (2019). The Use of Web 2.0 Technology Tools and beyond in Enhancing Task-Based Language Learning: A Case Study. The English Teacher., 48(1), 29–44.

Annamalai, N., & Kumar, J. A. (2020). Understanding Smartphone use Behavior among Distance Education Students in Completing their Coursework in English: A Mixed-Method Approach. Reference Librarian, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763877.2020.1815630

Apandi, A. M., & Raman, A. (2020). Factors Affecting Successful Implementation of Blended Learning at Higher Education. International Journal of Instruction, Technology, and Social Sciences (IJITSS), 1(1), 13–23.

Attaran, M., & Zainuddin, Z. (2018). How Students Experience Blended Learning? (Malaysian Experience). Interdisciplinary Journal of Virtual Learning in Medical Sciences, 9(2).

Azhari, F. A., & Ming, L. C. (2015). Review of e-learning Practice at the Tertiary Education level in Malaysia. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Education and Research, 49(4), 248–257. https://doi.org/10.5530/ijper.49.4.2

Barrot, J. S. (2014). A Macro Perspective on Key Issues in English as Second Language (ESL) Pedagogy in the Postmethod Era: Confronting Challenges Through Sociocognitive-Transformative Approach. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 23(3), 435–449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-013-0119-4

Bokolo, A., Kamaludin, A., Romli, A., Mat Raffei, A. F., A/L Eh Phon, D. N., Abdullah, A., Leong Ming, G., A. Shukor, N., Shukri Nordin, M., & Baba, S. (2019). A managerial perspective on institutions’ administration readiness to diffuse blended learning in higher education: Concept and evidence. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 52(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2019.1675203

Chomsky, N. (1968). Language and Mind. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511791222

Corbett, J. (2003). An Intercultural Approach to English Language Teaching. Multilingual Matters Ltd.

De Jong, N., Savin-Baden, M., Cunningham, A. M., & Verstegen, D. M. L. (2014). Blended learning in health education: Three case studies. Perspectives on Medical Education, 3, 278-288. doi:10.1007/s40037-014-0108-1

Frafika Sari, I., Rahayu, A., Apriliandari, D. I., & Dwi, S. (2018). Blended Learning: Improving Student’s Motivation in English Teaching Learning Process. International Journal of Languages’ Education and Teaching, 6(1), 163-170.

Gerstein, J. (2014). Moving from Education 1.0 through Education 2.0 towards Education 3.0. In L. Blaschke, C. Kenyon, & S. Hase (Eds.), Experiences in Self-Determined Learning (pp. 83–98). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

Hamidon, Z. (2018). The learner’s engagement in the learning process designed based on the experiential learning theory in post-graduate program at Open University Malaysia. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, 26–31. https://doi.org/10.1145/3291078.3291079

Hani Salim, Ping Yein Lee, Sazlina Shariff Ghazali, Siew Mooi Ching, Hanifatiyah Ali, N. H. S., Mawardi, M., & Dzulkarnain, P. S. J. K. D. H. A. (2018). Perceptions toward a pilot project on blended learning in Malaysian family medicine postgraduate training: A qualitative study. BMC Medical Education, 18(206), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1315-y

Harun, F., & Hussin, S. (2018). Speak Through Your Mobile App Changing The Game: English Language in Education 4.0. 27th Melta International Conference, 186–196.

Hase, S., & Kenyon, C. (2013). Self-determined learning: Heutagogy in action. Bloomberg Press.

Hinkel, E. (2006). Current Perspectives on Teaching the Four Skills. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 109–131. https://doi.org/10.2307/40264513

Hymes, D. (1970). On Communication Competence. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Isman, A. (1997). Students’ perception of a class offered through distance education (pp. 1-261). Ohio University.

Isman, A., & Dabaj, F. (2004). Roles of the students and teachers in distance education. In Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference (pp. 497-502). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE).

Khan, A. I., Shaik, M. S., Ali, A. M., & Bebi, C. V. (2012). Study of blended learning process in education context. International Journal of Modern Education and Computer Science, 4, 23-29.

Krashen, S. D. (1982). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Pergamon Press Inc.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2006). TESOL Methods: Changing Tracks, Challenging Trends. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 59–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/40264511

Lapitan Jr, L. D., Tiangco, C. E., Sumalinog, D. A. G., Sabarillo, N. S., & Diaz, J. M. (2021). An Effective Blended Online Teaching and Learning Strategy during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Education for Chemical Engineers.

Lim Jia Ying, C., Embi, M. A., & Hashim, H. (2019). Students’ Perceptions toward Gamification in ESL Classroom: KAHOOT! In V. Nimehchisalem & J. Mukundan (Eds.), Proceedings of the International Conference on Creative Teaching, Assessment and Research in the English Language (pp. 129–132).

Maarop, A. H., & Embi, M. A. (2016). Implementation of Blended Learning in Higher Learning Institutions: A Review of Literature. International Education Studies, 9(3), 41. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v9n3p41

Madarina, A., Rahman, A., Nazri, M., Azmi, L., & Hassan, I. (2020). Improvement of English Writing Skills through Blended Learning among University Students in Malaysia. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(12A), 7694–7701. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2020.082556

Maria, M., Shahbodin, F., & Pee, N. C. (2018). Malaysian higher education system towards industry 4.0 – Current trends overview. AIP Conference Proceedings, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5055483

Ministry of Education Malaysia (MoE). (2015). Executive Summary Malaysia Education Blueprint 2015-2025 (Higher Education). In Ministry of Education Malaysia (p. 40).

Mohd Zaki, M. H. S., & Abdul Aziz, A. (2019). The Use of Youtube in Developing Speaking Skill among ESL Learners in Malaysia. In V. Nimehchisalem & J. Mukundan (Eds.), Proceedings of the International Conference on Creative Teaching, Assessment and Research in the English Language (pp. 155–160).

Muhammad, A. S. I. F., Edirisingha, P., Ali, R., & Shehzad, S. (2020). Teachers’ Practices in Blended Learning Environment: Perception of Students at Secondary Education Level. Journal of Education and Educational Development, 7(2).

Muhammad, S. S., Idrus, M. M., Salleh, S. M., & Kadir, Z. A. (2020). Issues and Challenges in Blended Learning among Learners in Higher Education: What do we learn? International Journal of Education and Pedagogy, 2(4), 193-204.

Osman, N., & Hamzah, M. I. (2020). Impact of Implementing Blended Learning on Students’ Interest and Motivation. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(4), 1483-1490.

Otukile-Mongwaketse, M. (2018). Teacher-centered dominated approaches: Their implications for today’s inclusive classrooms. International Journal of Psychology and Counselling, 10(2), 11–21. https://doi.org/10.5897/ijpc2016.0393

Palalas, A. (2013). Blended mobile learning: Expanding learning spaces with mobile technologies. In A. Tsinakos & M. Ally (Eds.), Global mobile learning implementations and trends (pp. 86-104). China Central Radio & TV University Press.

Palalas, A. (2019). Blended language learning: International perspectives on innovative practices. China Central Radio & TV University Press.

Palalas, A. & Wark, N. (2020), The relationship between mobile learning and self-regulated learning: A systematic review. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 36(4), 151 -172.

Phipps, A., & St Clair, R. (2008). Intercultural literacies, Language and Intercultural Communication. Language and Intercultural Communication, 8(2), 69–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708470802270786

Qing-xue, L., & Jin-fang, S. (2007). An Analysis of Language Teaching Approaches and Methods-Effectiveness and Weakness. US-China Education Review, 4(1), 69–71.

Rasheed, R. A., Kamsin, A., & Abdullah, N. A. (2020). Challenges in the online component of blended learning: A systematic review. Computers & Education, 144, 103701.

Rheingold, H. (Ed.). (2014). The peeragogy handbook. Jointly published by Pierce Press and PubDomEd.

Salleh, F. I. M., Ghazali, J. M., Ismail, W. N. H. W., Alias, M., & Rahim, N. S. A. (2020). The impacts of COVID-19 through online learning usage for tertiary education in Malaysia. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(8), 147–149. https://doi.org/10.31838/jcr.07.08.30

Sasidharan, A. (2018). Executing reflective writing in an EAP context using Edmodo. The English Teacher, 47(2), 31–43.

Shamsuddin, N., & Kaur, J. (2020). Students’ learning style and its effect on blended learning, does it matter? International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education, 9(1), 195–202. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijere.v9i1.20422

Sidek, S. F., Yatim, M. H. M., Ariffin, S. A., & Nurzid, A. (2020). The Acceptance Factors and Effectiveness of Mooc in the Blended Learning of Computer Architecture and Organization Course. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 8(3), 909–915. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2020.080323

Singh, R., & Kaurt, T. (2017). Blended Learning – Policies in Place at Universiti Sains Malaysia. In Lim, C. Ping, Wang, & Libing (Eds.), Blended Learning for Quality Higher Education: Selected Case Studies on Implementation from Asia-Pacific (second, pp. 103–124). United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Skehan, P. (1998). A Cognitive Approach to Language Learning. Oxford University Press.

Sukma, E., Ramadhan, S., & Indriyani, V. (2020, March). Integration of environmental education in elementary schools. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1481(1), 012136. IOP Publishing.

Wahab, Nursyuhada’Ab, A. M. Z., & Yunus, M. M. (2018). Exploring the Blended Learning Experience among 21st Century Language Learners. Language & Communication, 5(1), 136-149.

Wang, M., & Kang, M. (2006). Cybergogy for engaged learning: A framework for creating learner engagement through information and communication technology. In Engaged learning with emerging technologies (pp. 225-253). Springer, Dordrecht.

Yamamoto, G. T., & Karaman, F. (2011). Education 2.0. On the Horizon, 19(2), 109–117. https://doi.org/10.1108/10748121111138308

Yan Ju, S., & Yan Mei, S. (2018). Perceptions and Practices of Blended Learning in Foreign Language Teaching at USIM. European Journal of Social Sciences Education and Research, 12(1), 170–176.

Yusoff, M. S. B., Hadie, S. N. H., Mohamad, I., Draman, N., Ismail, M. A. A., Rahman, W. F. W. A., Pa, M. N. M., & Yaacob, N. A. (2020). Sustainable medical teaching and learning during the covid-19 pandemic: Surviving the new normal. Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences, 27(3), 137–142. https://doi.org/10.21315/mjms2020.27.3.14

Yusoff, S., Yusoff, R., & Md Noh, N. H. (2017). Blended learning approach for less proficient students. SAGE Open, 7(3), 2158244017723051.