Elżbieta Gajek

Abstract

The aim of the chapter is to present and analyse eTwinning as a programme and community of educators from the perspective of a blended approach, with in-class and online work interwoven, that supports blended learning underpinned by various pedagogical approaches, such as problem-based learning, inquiry-based learning, situational learning, and collaborative learning. The analysis will show how eTwinning responds to the challenges of online teaching in the Polish context due to the Covid pandemic. The eTwinners proved to be better prepared for online teaching. They were also flexible enough to extend their previous experiences and use them immediately during the lockdown. Finally, the pedagogical approaches implemented in eTwinning projects will be illustrated by the examples of projects aimed at various educational levels and age groups.

Keywords: eTwinning, Blended Language Learning, Erasmus+ programme, pedagogical approaches; COVID

Introduction

eTwinning is a part of Erasmus+ programme. It supports collaborative learning and teaching among over 215 thousand schools in Europe and associate countries. eTwinning is also an online community of over 900 thousand teachers and educators in Europe and beyond. Since 2005 it has provided a means for teachers from two or more different European countries to collaborate in a safe online space on curriculum-based projects. The initial broad idea has been developed over time by and for teachers and has grown organically in response to their needs within the context of changing educational and social environments, such as increasingly diverse classrooms, and major technological innovations. It responds to the call for change in education for empowering learners and giving more agency (Vincent-Lancrin, 2019).

Overview of the eTwinning program

The top-down perspective emphasises the following qualities of eTwinning. To shorten the description, it will be presented in the form of lists, which highlight the essentials of the programme. The summary below is based on the recent eTwinning Report 2019 (Gilleran, 2020a).

eTwinning provides digital infrastructure for:

- Collaborative educational purposes at primary and secondary level and for teacher training institutions;

- A safe, password-protected, digital collaborative space for teachers and learners – Twinspace, where educational content and resources can be stored and shared. Links to other tools can also be included, depending on the needs;

- Communication via online fora and video conferencing facilities;

- Building an authentic context for the development of technological skills in schools;

- An inclusive and accessible platform for all learners, regardless of needs, abilities, or socio-economic background.

eTwinning provides organisational support to its participants through:

- National Support Services (NSS) and Partner Support Agencies (PSA) – in 44 member countries and with the supervision of the Central Support Service, coordinate the work of eTwinning at national level;

- Each country provides support to schools at national level, including recruitment support and training of school staff, and management of ambassador networks;

- A network of eTwinning ambassadors – teachers experienced in eTwinning – provide peer support and mentoring to the wider eTwinning community;

- It supports collaboration among teachers and learners through national promotional activities and events.

eTwinning provides integrated pedagogical framework. It is a very flexible programme. The only requirement for an eTwinning project is that there must be at least two schools teaching learners between 3-19 years old, from two European countries. In particular, in eTwinning:

- There are no constraints regarding the content, number of partners and participants in a project, means of communication, language or languages of communication, time limits, forms of assessment, compliance with the partner’s curriculum;

- Holistic teaching approaches, creativity, collaboration, problem solving, effective use of technology for educational purposes are encouraged;

- Collaborative problem solving and project-based pedagogical approaches are put into practice;

- Digital technology is seen as a means of implementation of various pedagogical approaches;

- The use of foreign languages of the participants’ choice finds its natural environment.

eTwinning enhances compliance with curricula as it:

- Allows teachers to fulfil the requirements of their own curriculum, but also often go beyond it;

- Enhances teacher creativity as the content created in collaboration with partners can cover any curriculum area: eTwinning projects often involve teachers from a range of subject areas, such as ICT and languages, for example, or maths and history, climate change and environmental issues;

- Enhances a variety of assessment techniques as teachers may negotiate evaluation procedures that respond to the needs of all partners.

eTwinning supports European integration as it:

- Puts European integration into practice in creative and innovative ways which are practical and appropriate, which can be elaborated exclusively in schools;

- Facilitates contact, communication and collaboration among teachers in various European countries and beyond;

- Explores and encourages shared values amongst teachers and students who participate in eTwinning projects.

Local perspective on eTwinning in Poland

The implementation of the eTwinning program depends on local learning opportunities and conditions. In Poland eTwinning was introduced in December 2004. Since the very beginning teachers have responded to it willingly with over 100 projects in the very first year (Gajek, 2005). The number of teachers and schools has been growing as a result of strong organizational support of eTwinning National Support Service (NSS). Teachers were introduced to the program via face-to-face teacher training sessions and an online 10-week-long course titled “How to participate in eTwinning?”, prepared by Elzbieta Gajek, launched in 2006. Thousands of Polish teachers have completed the course and it is still in the NSS offer. It was a starting point for various short online teacher training courses which responded to the needs of the participants. In 2019 eTwinning was included as a recommended form of practice in the Polish curriculum for teaching modern languages at the secondary educational level.

The bottom-up perspective emphasises the blended approach to learning and teaching as each project involves teachers’ and students’ work in-class and online collaboration with partners. It is embedded in the local circumstances as all projects need to fit local curriculum, infrastructure, socially accepted teaching practices. The partners negotiate the details of a planned project to make it manageable in their context. However, there are four generic stages which are interchangeably done on site and through the digital tools which are observed in the majority of the projects. The local perspective also involves the school community that includes parents, grandparents, experts, local educational authorities, and media if needed and relevant.

Firstly, it is the blended preparation stage, which is done with the use of communication digital tools. The teachers find the partners using partner finding functionalities of eTwinning platform. Then, they form a partnership. They negotiate the aims, means of communications, and content of the project. As the program is very flexible, they autonomously plan the structure, timing, and expected outcomes of the project in detail.

Secondly, it is the blended action stage done with the use of digital tools appropriate for the content of the project. Partners collect and exchange information, and then share their work; the most essential part is collaboration. Thus, learners work in international groups while preparing the results of their work. They collate their findings to prepare a common product, for example, a book.

Thirdly, it is the blended consolidation and evaluation stage. Participants reflect on their work. They collate the individual partner results or shared work of different subgroups into common refined and graphically elaborated products. The teachers, learners, and sometimes other stakeholders reflect on the outcomes and evaluate the results of the project using quantitative or qualitative methods. They identify the main strengths and weaknesses of the project and usually plan for the next edition of the project ideas.

Fourthly, it is the dissemination stage done with the use of presentation and publishing tools. The partners report the results, publish them, and disseminate among the school community, on the school websites, and in social media. Teachers often invite colleagues from other schools in the neighbourhood and together with learners share their experiences. The outcomes are also presented during various teacher training sessions and conferences.

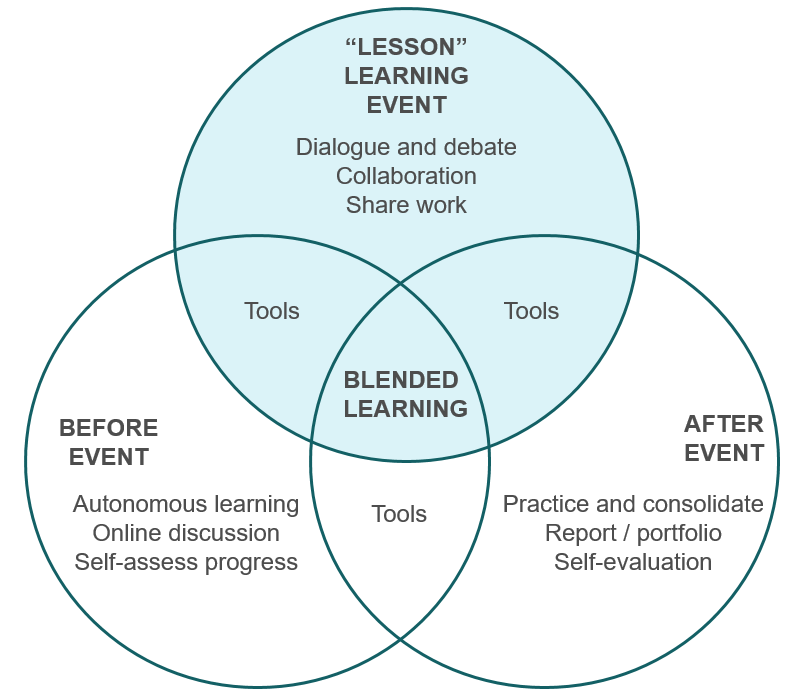

In the programme, teachers are offered freedom in the creation of the learning environment which involves collaboration, play and inquiry, which are perceived as essential factors of innovative pedagogies (Paniagua & Istance 2018). This bottom-up approach reflects a pedagogical vision of blended learning seen as a combination of activities mediated by digital tools as illustrated in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1

Blended Learning Implemented in eTwinning (source: Gilleran, 2020b, p. 3, based on Liu et al., 2017).

Pedagogical Approaches

Anne Gilleran, who is the visionary founder of eTwinning, indicates the two basic pedagogical approaches on which the programme is built as inquiry-based learning and problem-based learning. She suggests creating an environment in which four steps of inquiry-based blended learning are involved: (1) Students develop questions they are hungry to answer, (2) Students research the topic, (3) Students have the opportunity to present what they have learnt, (4) Students have a chance and are encouraged to reflect on their activities and evaluate what successes they achieved and what did not work. The final advice is that teachers need to accompany students and provide guidelines and support them through all stages above. She claims: “Students acquire and analyse information, develop and support propositions, provide solutions, and design products that demonstrate their thinking and make their learning visible” (Gilleran, 2020b, p. 7).

Project-based learning requires four steps: 1) identifying the question (problem) which is sophisticated enough, preferably which should not have one right answer so that students are able to demonstrate deep understanding of content to be answered; 2) giving context meaning that students need to be supported in their self-directed learning to feel challenged and encouraged to learn more and find the solution to the problem; 3) working in cooperative groups to find a solution; thus, a framework and structure for group work need to be clearly set, if possible after negotiations with participants both partner teachers and learners; 4) providing opportunities for presenting solutions; this depends on the age, skill level and cognitive potential of the learners; they demonstrate their acquired skills and knowledge using an e-book, audiovisual presentation, magazine, game, etc. Gilleran observes that “[s]uccessful problem-solving often requires students to draw on lessons from several disciplines and apply them in a very practical way. The promise of seeing a very real impact becomes the motivation for learning” (Gilleran, 2020b, p. 8).

- region culture;

- Environmental issues;

- Visual arts and music;

- Knowledge of specific subjects;

- Multilingual and multicultural cooperation;

- Themes neglected in the curriculum (Gajek, 2006, 2007).

The main categories have some emphasis on current social discourse or new opportunities. For example, safety on the internet has gained more attention since 2012 alongside with the Safer Internet Day. Intercultural issues were discussed 2008-2015 going beyond simple facts and comparisons, more orientated on intercultural reflection, challenging stereotypes, xenophobia and intolerance (Gajek, 2017) or recent focus on climate change in 2020.

The processes which enhance collaboration among teachers and students vary depending on the needs of the participants. At least two teachers envisage a draft of their mutual work. Then, they go to their classes where the teacher initiates the project and negotiates its content with learners. Even young learners are able to contribute to the development of the project: they can refine its focus or introduce strategies of project work. Then, iteratively the teachers and learners come up with a detailed plan of a project. At this stage collaboration is twofold. It takes place in class and with foreign partners outside of the class. The outer modes of collaboration fall into various categories. At the beginning, the most popular mode involved the preparation of materials for partners and exchanging them, e.g., presentations about schools, local customs and traditions, exchanging songs and recordings of dances for partners to sing and dance or recipes of local dishes for cooking. Some partners, especially in Great Britain, developed a star-like pattern: each class in a school contacted a school in a different country; they collaborated collecting information about the partners’ cultures and shared their knowledge in an all-school European day. Since the first Safer Internet Day was introduced in 2012, the schools have celebrated it collaboratively focusing on its message. An effective mode of collaboration is appointing a mascot which physically travels among the partner schools, while the others observe and follow activities performed in each partner school. Within each subject teachers creatively develop subject specific forms of collaboration. In science, they do experiments planned together and share the results. In sports, they exchange kinesthetic games popular in their regions, play them and share the recordings. In languages, they write collaboratively their own story or illustrate masterpieces of literature. In art, they select masterpieces together and take photos of reconstructions of the pictures with them as models. With years the new preferred mode of collaboration has gained great acceptance. That is a collaboration towards a preparation of common final products. All partners work on materials which are then collated in the form of, for instance, an e-book. In many projects learners are grouped in multinational teams. Then they take a subtopic of the main theme of the project and work together towards the final outcome. The results of groupwork are collated and presented as a unit to display a shared common work. This mode is especially effective with teenagers as they have an opportunity to communicate in a foreign language while working on the project theme. It allows for authentic communication among children.

Whatever mode of collaboration is implemented, the learners need to be guided, supported, and motivated to achieve the final satisfactory result. Appropriate techniques need to be implemented depending on the age of the participants.

Studies on the Teacher’s Response to Online Teaching

The general report on online education during the pandemic published in April 2020 showed that 85% of teachers in Poland did not have any experience in online teaching. However, 49% of them did not report any problems with computer literacy and the use of digital tools. They admitted that learning the new tools was time consuming but achievable (Buchner et al., 2020). They mainly relied on local solutions and local resources (Buchner & Wierzbicka, 2020).

The survey on Polish eTwinners published in 2020 showed that teachers who regularly had participated in the programme continued doing so. The survey collected feedback from 1790 respondents and was supported by the analysis of active participation of 1621 teachers in the eTwinning platform. The teachers in eTwinners did not complain about the lack of computer literacy. They actively participated in webinars offered to them as a form of support and teacher training. The results of the study confirmed that teachers who had been active in the programme and had been familiar with digital collaborative tools had no difficulty in staging classes online at the moment of lockdown (Fila et al., 2020)

Examples of Projects

eTwinning projects’ content and management are adjusted to the needs and cognitive potential of the learners and competences of the teachers. To illustrate the above collaborative blended approach, five projects will be presented in detail in the light of the pedagogical approaches applied in each one.

A Project for Children 3-6 Years Old Learners

The project titled Travelling ROBOT was created by partners from Poland, Turkey, Malta, Italy, Portugal, Serbia, and Czech Republic. The project started in January 2019 and finished in June 2020. Despite the pandemic, a robot Ozzie travelled among the partners to help little children to acquire computational thinking alongside with the development of speech in the native and foreign languages, development of openness to other people. Children designed routes and houses for Ozzie, named objects and learnt the basics of programming. They also learnt how to document their work and share it with others. They monitored Ozzie’s trip on maps and via video conferences learning about other countries while practicing intercultural communication and collaboration with peers. The results of the project are available in the project open Twinspace at https://twinspace.etwinning.net/80207/pages/page/950326. In this project, computer literacy was the main aim and digital tools were the means of communication and means of instructions as the children played with the Ozobots. The framework of the collaborative learning environment allowed for the development of children’s creativity and autonomy in the exploration of the world. With this age group, the activities are planned to activate learners carefully taking into consideration their cognitive and learning potential.

Two Projects for 7-10 Years Old Learners

The project Make Friends with Pippi is aimed at celebrating the 75h anniversary of Pippi Langstrumpf. Twenty-three partners from Bulgaria (1), Greece (3), Holland (5), Poland (11), Serbia (1), and Turkey (2) have built their activities around the literary work since September 2020. They created an e-book which illustrates their approaches to blended learning available at https://twinspace.etwinning.net/119789/pages/page/1140748 , which combined in-class and virtual learning. In this project special education needs children were actively involved. They discussed bullying, made exhibitions, and visited a home-made zoo in which children played the roles of animals doing kinesthetic activities. They developed habits of reading, listening, writing, singing about Pippi, and multimodal transfer of information by illustrating Pippi’s activities and many other creative tasks, e.g., searching for things. Based on Pippi’s adventures and ideas, they built unique bonds not only with peers but also with nature: plants, trees, and animals. The pandemic did not stop the development of the project. What is more, parents got involved helping with activities that could not have been completed in class during the lockdown. One of the teachers reported that children who were closed at home had more time for the project activities, so they could discover their talents and interests for acting, drawing, and working with digital tools.

English and Puzzles eTwinning project is focused on learning English through digital games, quizzes, and puzzles. Nine partners from Greece, Spain, North Macedonia, Poland, Serbia, Turkey, Ukraine, Hungary, and Italy created the materials together and made them available on their blog https://englishandpuzzles.blogspot.com/. This project started in September 2019 and continued smoothly in the pandemic.

A Project for 11-14 Years Old Learners

The project Bits and Pieces of Culture is a synergy project in Erasmus+ and eTwinning to enhance face-to-face contacts allowed in Erasmus+ projects with online work with the use of eTwinning tools. Six countries participated: Croatia, Poland, Greece, Spain, Cyprus, and Italy. They started the project in 2018 and they have continued it since then. Its aim was to explore various aspects of the culture of the partner countries. Their website https://bitsandpiecesofculture.weebly.com/ and blogs illustrate well how they smoothly passed from face-to-face meetings to virtual meetings continuing their work plan. It is not a typical eTwinning project because it involved travelling included in Erasmus+ projects before the pandemic, but it is well documented on publicly available websites, which is not common due to GDPR and safety regulations that protect student’s images and data. Virtual work in international groups enhanced communication skills and ability to collaborate. The areas of culture discussed and shared in the project were extensive covering high culture, literature, art, music, historical remains, and pop culture, such as cuisine, seasonal festivals, and board games. They played home-made guessing games and quizzes related to masterpieces of art. They replicated the pictures of the masterpieces designing their own sceneries and practiced audio description of pictures. They also shared Christmas cards and ornaments, sending them to partners by post, sang together carols, folk songs coming from the partners’ regions. They designed together choreography for a common dance. They took pictures of architecture and nature (Four themes: water, fire, air, and earth).

A Project for 15-19 Years Old Learners

The project IroName Island is aimed at learning a language in communication with foreign partners. Nine partners contributed to the development of the project: Azerbaijan, Georgia, Spain, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Turkey, and Ukraine. It started in September 2019. Participants created international teams that were called for example Phrasal Verbs, Irregular Verbs, Adjectives, etc., and they co-created multimedia materials, interactive games, mind maps, a dictionary, audiobooks, and an e-book for learning English, all available at https://twinspace.etwinning.net/91798/home. Thus, it is an example of learning by doing where the language is the target and means of communication in the blended multilingual and multicultural environment. The pandemic lockdown did not have any impact on the project activities. It did not stop them in developing all language and communication skills in an international multicultural collaborative environment with English as a means of instruction and the aim in itself.

Digital Tools Used in the Projects

Participation in the projects provide a natural learning environment for trying out various digital tools and applying them according to the needs. Various applications are used accordingly at all stages of the project development. Table 1 presents the selection of tools for various purposes.

Table 3.1

Digital Tools for Various Purposes

| Project Activities | Examples of Tools |

| Project posters logos | Canva Logomaker Poster Maker RedenForest Postermywall |

| Map of partners’ schools | Google Maps, MapLoco, Tripline Zeemap Pictramap |

| Timeline | Flipidity, Powtoon |

| Surveys, Votes, Evaluations | Google Forms, Pollmaker, Tricider, Wakelet SurvryMonkey AnswerGarden |

| Checklists, lists of groups | Google sheets TwinSpace Table |

| Partners’ presentations | Wakelet Kizoa Biteable Animoto Animaker MsMovieMaker RedenForest Phrase.it Voki VoiceThread BlabbeRize AvatarMaker Avachara PhotoTalks FactoryForAvatars TellaGami Youtube Quik |

| Schools’ presentations | Emaze Prezi Kizoa Visme Biteable GoogleSlides Piktochart Animaker MsMovieMaker RedenForestQuik Youtube Knovio Voki Create Avatar Scoompa Video |

| Video making and editing | Scoompa InShot Flexiclip Voki Create Avatar Animoto, Kioza Animaker Biteable Flixpress VivaVideo TellaGami |

| Discussions and communication | TwinSpace Journal, Facebook Messenger Twinspace Forums Messenger Chat Groups, WhatsApp Edmodo Skype Adobe Connect Hang Outs Zoom Flipgrid Doodle |

| Taking notes and making mindmaps | Evernote Lino Mindmeister Coggle |

| Cartoons and avatars | Avachara Voki Create Avatar Avatar Maker FactoryForAvatars Toontastic Phrase.it PhotoTalks |

| Infographics | Pictochart |

| Project blog | Blogspot, Blogger |

| Activity Photos, photo editing | Padlet, Adobe Spark Joomag, Canva, Story Jumper, Madmagz, Paint Befunky Incollage Paint Pixlr Ipiccy InShot Tuerchen |

| 3D design | Thinkercad |

| Collaborative area | Jamboard Padlet Sway Pearltrees VoiceThread |

| Exchanging instructions | QR code tools |

| Comparing opinions | Mentimeter |

| Collage | BeFunky pixi Piccollege |

| Classroom Applications | ClassDojo Google Classroom Thinglink |

| Audio recording and editing | Audacity Vocaroo |

| Storyboard creators | StoryboardThat |

| Games | LearningApps BookWidgeds JigsawPlanet Gimkit Quizziz Quizlet Actionbound Crosswordlabs.Com Kahoot |

| Project websites | Weebly |

| Statistics | IBM Statistics 20 |

| Final products and publishing | Blogspot Quik Powtoon Moviemaker Bookcreator, Smore Google slides Calameo Genial.ly Wordart Storyjumper Youtube issuu Flippity Wordart Prezzi |

Table 3.1 shows that appropriate tools are used at the beginning for planning, creating the map of the partnership, creating timelines, generating ideas, and brainstorming. During the project other tools are needed for checklist, lists of teachers and learners, for introductions of the participants, for discussions, development of the project logo and posters, for voting, blogging, communicating among partners. Then, other tools are utilised for collecting data, doing evaluation, and performing statistical analysis of the results. Finally, the project outcomes need to be published and disseminated with the use of other tools.

Discussion of Pedagogical Approaches in the Projects

Although the selection of projects to illustrate eTwinning activities is very limited in scope, it is noticeable that everything is undertaken within a blended approach as the work was done partially in class and partially through the computer mediated communication and collaboration with partners. None of the projects presented, as well as many others that started before the pandemic, has been discontinued. What is more, some of them only changed their activities slightly or even intensified them. This means that both teachers and learners had been well prepared for online educational work in terms of digital and intercultural competences, collaboration and communication patterns to proceed in the changed environment.

All eTwinning projects are based on collaboration with the emphasis on shared work on common products preferably in international groups of students. This creates a learning environment in which students use a foreign language and digital tools for communicating, producing shared results, reflecting, and evaluating their work.

Both inquiry-based approach and problem-based approach are used depending on the requirements of the content, structure of the individual project, and cognitive potential of the learners. Pedagogical approaches centred on learners are put into practice in an enjoyable and pleasurable way appropriately to the age, cognitive level, as well as needs of the learners.

Developing Competences Through eTwinning Activities

eTwinning programme contributes to building a meaningful environment for developing various competences in learners and teachers. As eTwinning activities fully respond to the curriculum requirements of the partner countries, the reference to the recent version of key competences has to be ensured. The last version of eight key competences for lifelong learning covers:

- Literacy competence;

- Multilingual competence;

- Mathematical competence and competence in science, technology and engineering;

- Digital competence;

- Personal, social and learning to learn competence;

- Citizenship competence;

- Entrepreneurship competence;

- Cultural awareness and expression competence (Key Competences for lifelong learning, 2019).

The selected examples of the projects demonstrate that children develop competences such as literacy skills, they communicate in foreign languages while using digital tools purposefully. Cooperation in international groups contributes to the development of personal and social as well as citizenship and entrepreneurship competences. Whatever they do in a project, it refers to their cultural expression.

Teachers who initiate and participate in eTwinning projects also develop key competences for lifelong learning among themselves. Real-life communication in foreign languages with adults is particularly important for those teachers who work with young learners and use simplified language on an everyday basis. They also develop professional pedagogical competences such as language and communication skills, including online communication and intercultural skills. They learn about educational systems and curricula in the partner countries. The learning environment that they create enhances the core blended learning skills such as ICT skills, including coding internet safety and media literacy but without leaving neglected interpersonal skills in human communication. The teachers also acquire managerial skills, such as project management, team-working, shared decision-making, and cooperation that help them to demonstrate to learners how to work independently, and how to take initiative. They become role models of self-confident and self-directed learners, open-minded and able to collaborate in intercultural and multilingual contexts.

The competences developed within an eTwinning project contribute to the teachers’ confidence in the use of online tools and teaching strategies. Thus, the cooperative work among the teachers prepared them for online teaching challenges imposed on teachers and learners due to the pandemic.

Conclusions

The presented examples and analyses show that participation in blended learning eTwinning projects served well as complementary educational activities before the pandemic. The fact that all the projects continued after the school lockdown illustrates that teachers who had gained competences and skills necessary for blended learning used them effectively in the time of lockdown. They were well prepared for a smooth transition into the new circumstances and challenges. Moreover, there is some evidence that the project work helped to overcome the feeling of “being trapped” to some extent as the participants were able to continue collaboration with their partners abroad.

The general final conclusion relates to the innovative attitudes of teachers at all educational stages. Teachers are encouraged to experiment with innovations and broaden their teaching competences even beyond the actual requirements of the curricula and accepted teaching habits as the eTwinners had done before the pandemic. This helps to overcome an unexpected crisis and overcome the challenges and difficulties the change brings about.

References

Buchner, A., Majchrzak, M., & Wierzbicka, M. (2020, April). Edukacja zdalna w czasie pandemii part 1. Centrum Cyfrowe. https://centrumcyfrowe.pl/edukacja-zdalna/#Raport

Buchner, A., & Wierzbicka, M. (2020, November). Edukacja zdalna w czasie pandemii part 2. Centrum Cyfrowe. https://centrumcyfrowe.pl/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/2020/11/Raport_Edukacja-zdalna-w-czasie-pandemii.-Edycja-II.pdf.

Fila, J., Jeżowski, M., Pachocki, M., Rybińska, A., Regulska, M., & Sot, B. (2020). Teachers Online eTwinning Users Survey Report. Foundation for the Development of the Educational System. https://issuu.com/frse/docs/raport-etwinning_en_final

Gajek, E. (2005). eTwinning Europejska współpraca szkół Polska 2005 /European Partnerships of Schools Poland 2005. Fundacja Rozwoju Systemu Edukacji.

Gajek, E. (2006). eTwinning Europejska współpraca szkół Polska 2006 /European Partnerships of Schools Poland 2006. Fundacja Rozwoju Systemu Edukacji.

Gajek, E. (2007). eTwinning Europejska współpraca szkół Polska 2007 /European Partnerships of Schools Poland 2007. Fundacja Rozwoju Systemu Edukacji.

Gajek, E. (2017). Curriculum integration in distance learning at primary and secondary educational levels on the example of eTwinning projects Challenges and Future Trends of Distance Learning. Education Sciences 8(1), 1-15. doi:10.3390/educsci8010001

Gilleran, A. (2020a). eTwinning in an era of change – Impact on teachers’ practice, skills, and professional development opportunities, as reported by eTwinners – Full Report. Central Support Service of eTwinning. European Schoolnet.

Gileran, A. (2020b). Empowering future teachers with eTwinning. The pedagogy of eTwinning. Workshop 24-26, November 2020.

Key Competences for Lifelong Learning (2019). European Commission. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/297a33c8-a1f3-11e9-9d01-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

Liu, H., Kolg, D., Zhang, Z., Shu, J., & Cao, T. (2017). Cloud-class Blended Learning Pattern Innovation and Its Applications, Proceedings of the 2017 International Symposium on Educational Technology, Hong Kong. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318099730_2017_International_Symposium_on_Educational_Technology_ISET_2017

OECD (2018). What does innovation in pedagogy look like?, Teaching in Focus, No. 21. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/cca19081-en

Paniagua, A., & Istance, D. (2018). Teachers as Designers of Learning Environments: The Importance of Innovative Pedagogies, Educational Research and Innovation., OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264085374-en

Vincent-Lancrin, S., Urgel, J., & Kar, S. (2019). Measuring Innovation in Education 2019: What Has Changed in the Classroom?, Educational Research and Innovation. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264311671-en