Meredith Reese

Introduction

Obesity is commonly linked to heart disease, stroke, and diabetes however the location of the fat is an even better indicator of projected health outcomes. Men tend to carry their weight on the top of their bodies forming an android shape whereas women tend to carry their weight on their hips and thighs forming a gynoid shape. Android shape looks like an apple shape and gynoid shape looks like a pear shape. The android body shape puts more weight on internal organs increasing the likelihood of men developing heart disease (Samsell et al., 2014).

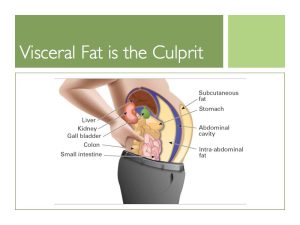

Fat Layers in the Abdomen

Within the abdomen, there is a layer of subcutaneous fat just below the skin and visceral fat located deeper into the abdomen. Visceral fat surrounds internal organs and is more dangerous than subcutaneous fat. Men on average carry more visceral fat than women while women tend to carry more subcutaneous fat which may be due to reproductive purposes (Després et al., 2008). Visceral fat is linked to metabolic syndrome, increased risk of heart disease, and type 2 diabetes, thus men are more likely to develop heart disease (Després et al., 2008). Research has shown that the amount of visceral fat that an individual has is an important indicator for patients at risk of cardiovascular events (Gruson et al., 2009). The easiest way to assess visceral fat is to calculate the waist-to-height ratio by dividing waist by height measurements. This waist-to-height measurement has been found to be a more accurate indicator for coronary risk than waist-to-hip ratio and waist circumference (Gruson et al., 2009). Men with a waist-to-height ratio over 0.54 are considered abdominally obese. As the waist-to-height ratio increases, the likelihood of heart disease increases, so it is crucial to try and avoid gaining visceral fat.

Populations at Risk

Race, age, and socioeconomic status are key potential factors to assess when determining a person’s likelihood of developing abdominal obesity. Socioeconomic class includes components such as income, occupation, and education. Among US-born men, Hispanics have the highest chance of having abdominal obesity, with White men being the second-highest group (Wen et al., 2013). This may be due to genetic or behavioral factors such as eating habits, exposures, and physical activity. Abdominal weight gain is linked to psychological stress and emotional instability which men are more likely to experience (Wen et al., 2013).

Abdominal obesity is an indicator of chronic diseases across all age groups, so it is very important that men prioritize their health from an early age. If a child has a history of obesity, then he is more likely to have heart disease and type 2 diabetes as an adult. Android and gynoid fat ratios are associated with both insulin resistance and dyslipidemia in 7-13-year-old boys regardless of whether obese or normal weight (Samsell et al., 2014). The location of the boy’s body fat, whether android and gynoid, has been highly correlated to metabolic and heart diseases in normal-weight boys (Samsell et al., 2014). Primary care providers and parents can use this information to assess which children are at risk for developing future diseases and work on lifestyle behavior changes.

Prevention

In order to prevent abdominal obesity, men must prioritize exercising and eating healthier. Participating in daily physical movements has been found to reduce abdominal weight in both men and women (Ekelund et al., 2011). Physical activity can include recreational activities such as swimming and jogging as well as maintaining a job that requires manual labor or frequent standing. Aim to participate in activity at least 30 minutes a day. Aerobic exercise and resistance training can lead to lowered abdominal weight in both children and adults (Samsell et al., 2014). Low calorie and high protein diets such as beans, peas, fish, and eggs with interval training can lower abdominal obesity in adults (Samsell et al., 2014). Plant-based diets can also be very helpful in reducing abdominal obesity because they contain less sugar and more fiber. Reduction in stress can be linked with decreased abdominal fat. Increased levels of cortisol, the stress hormone, cause increased insulin levels. The increased levels of insulin in the blood increase craving for fatty and sugary foods causing people to eat more of these unhealthy foods, thus gaining weight (Hewagalamulage et al., 2016).

Treatment Options

Most treatment options combine a diet and exercise-focused approach. The goal of treatments for abdominal obesity is not necessarily weight loss, but a decrease in waist circumference. The most successful form of treatment to reduce abdominal fat is an increase in physical activity while maintaining a low-calorie diet (Kesztyüs et al., 2018). Going to counseling has shown to improve weight loss when combined with diet and exercise to decrease visceral fat, thus decreasing the likelihood of heart disease and other chronic conditions. People who are abdominally obese and have already faced a heart attack are still at risk for a second heart attack even if they are on treatments meant to lower the side effects of abdominal obesity (Pratt, 2020). Medication alone is not enough to reduce the risk of heart attacks in abdominally obese individuals. Instead, they must focus on making healthier lifestyle changes in order to improve health outcomes. Additional treatments include surgeries that remove fat or shrink stomach size but are not recommended over diet and exercise-focused approaches.

Chapter Review Questions

1. What male population is most at risk for developing abdominal obesity?

A. Asian

B. Black

C. White

D. Hispanic

2. Men are more prone to develop this condition because they are more likely to carry:

A. Muscle

B. Visceral fat

C. Cortisol

D. Subcutaneous fat

3. All of the following can reduce one’s likelihood of developing abdominal obesity EXCEPT:

A. Exercising

B. Eating a low carbohydrate and high protein diet

C. Sleeping less

D. Decreasing stress levels

References

Després J.-P., Lemieux, I., Bergeron, J., Pibarot, P., Mathieu, P., Larose, E., Rodés-CabauJ., Bertrand, O. F., & Poirier, P. (2008). Abdominal obesity and the metabolic syndrome: Contribution to global cardiometabolic risk. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 28(6), 1039–1049. https://doi.org/10.1161/atvbaha.107.159228

Ekelund, U., Besson, H., Luan, J., May, A. M., Sharp, S. J., Brage, S., Travier, N., Agudo, A., Slimani, N., Rinaldi, S., Jenab, M., Norat, T., Mouw, T., Rohrmann, S., Kaaks, R., Bergmann, M. M., Boeing, H., Clavel-Chapelon, F., Boutron-Ruault, M.-C., & Overvad, K. (2011). Physical activity and gain in abdominal adiposity and body weight: Prospective cohort study in 288,498 men and women. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 93(4), 826–835. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.110.006593

Gruson, E., Montaye, M., Kee, F., Wagner, A., Bingham, A., Ruidavets, J-B., Haas, B., Evans, A., Ferrieres, J., Ducimetiere, P. P., Amouyel, P., & Dallongeville, J. (2009). Anthropometric assessment of abdominal obesity and coronary heart disease risk in men: The PRIME study. Heart, 96(2), 136–140. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2009.171447

Harvard Health Publishing Harvard Medical School. (2017, January 20). Abdominal obesity and your health. https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/abdominal-obesity-and-your-health

Hewagalamulage, S., Lee, T., Clarke, I., & Henry, B. (2016). Stress, cortisol, and obesity: a role for cortisol responsiveness in identifying individuals prone to obesity. Domestic Animal Endocrinology, 56, S112–S120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.domaniend.2016.03.004

Kesztyüs, D., Erhardt, J., Schönsteiner, D., & Kesztyüs, T. (2018). Therapeutic treatment for abdominal obesity in adults. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 115(29-30), 487–493. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2018.0487

Pratt, E. (2020, January 20). Belly fat linked to increased risk of repeat heart attacks. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health-news/belly-fat-linked-to-increased-risk-of-repeat-heart-attacks

Samsell, L., Regier, M., Walton, C., & Cottrel, L. (2014). Importance of android/gynoid fat ratio in predicting metabolic and cardiovascular disease risk in normal weight as well as overweight and obese children. Journal of Obesity. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A421211875/AONE?u=clemsonu_main&sid=AONE&xid=fb7ae3c0

Wen, M., Kowaleski-Jones, L., & Fan, J. X. (2013). Ethnic-immigrant disparities in total and abdominal obesity in the U.S. American Journal of Health Behavior, 37(6), 807–818. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.37.6.10

a syndrome marked by the presence of usually three or more of a group of factors (such as high blood pressure, abdominal obesity, high triglyceride levels, low HDL levels, and high fasting levels of blood sugar) that are linked to increased risk of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes

reduced effectiveness to insulin by the body's insulin-dependent processes (such as blood sugar uptake and breakdown of fats) that is typical of type 2 diabetes but often occurs in the absence of diabetes

a condition marked by abnormal concentrations of fat in the blood