17 Challenges Ahead

Key Concepts

In this chapter, we will:

- See a summary of the lessons learned from this book

- Learn why we still cannot solve all collective action problems

- Get exposed to the big challenges we are still facing in governing coupled infrastructure systems

17.1 What have we learned?

This book has provided an introduction to the study of institutions and governance in general and of governance of the coupled infrastructure systems in particular. Coupled infrastructure systems face the problem of under-provision, under-maintenance and over-extraction of the affordances. Despite the difficult challenges associated with governing these systems, we see successful performance of many shared resources especially in small-scale communities. We need to extend the lessons learned from these successes to better understand the general properties of different approaches to successfully governing the coupled infrastructure systems.

Elinor Ostrom developed a coherent theoretical framework that enables scholars to clearly articulate how institutional arrangements can facilitate successful governance of the commons (shared resources and infrastructures) . By institutions we refer to the prescriptions that humans use to organize all forms of repetitive and structured interactions. The prescriptions are rules and norms. They apply not only to common-pool resources such as groundwater, but also to other types of social dilemma situations like traffic, outer space, digital commons, sports, and health care.

Rules can be written laws, or agreed upon and commonly understood verbal rules in a community. Norms do not include explicit consequences if forbidden activities are performed or requirements are not met. Even though it may not be explicit, not following social norms may have negative consequences since people may decide to avoid interacting with people who have bad reputations.

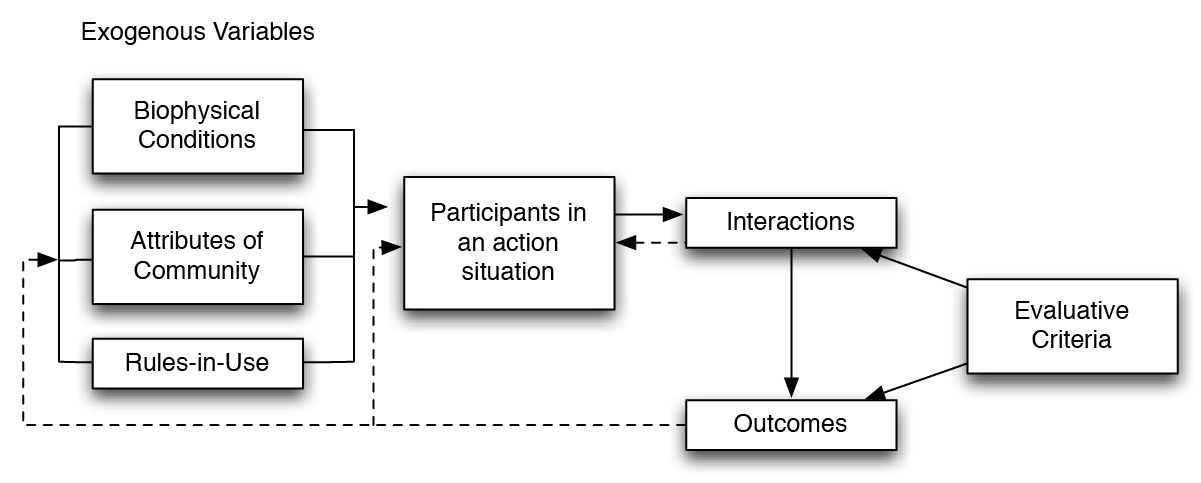

A key concept in studying institutions is the action arena. An action arena consists of people as participants and an action situation in which they participate. When people interact in an action situation, they make decisions based on the choice rules associated with the position they occupy in that action situation. In a given action situation, people may hold different positions and therefore may not be able to make the same decisions, or have the same information. The interactions of the participants lead to outcomes that can be evaluated.

Figure 17.1 shows the schematic representation of the Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework and highlights the key components necessary for studying how institutions structure action situations. The IAD framework emphasizes the fact that action situations are influenced by broader contextual variables. The biophysical conditions—whether you live in a desert or a rainforest—affect rules and norms concerning how to build houses and how to organize health care (e.g., due to different diseases that are prevalent in a given area). The attributes of a community such as the age and income distributions, education, and kin-relationships, affect which kind of interactions one can expect in action situations.

The rules-in-use are one of the key foci of the IAD framework. Rules on paper are important, but if those rules are not known, understood, and accepted by participants in the action situation, they will not effectively guide behavior. In studying the governance of the commons, we are interested in which rules people actually use, how they monitor rule compliance, sanction rule infractions, and how contextual variables impact how the rules function.

We have illustrated the application of the framework through several examples. The framework is just that—a framework. Frameworks are an articulation of key elements that should be considered when trying to understand the impact of institutional arrangements on human behavior and social interactions. The framework provides a set of concepts and language that enables scholars to communicate effectively about the key working parts of an action situation. Thus, if a student has developed a working knowledge of the IAD framework, they should be able to translate observations of social phenomena into the language of the IAD Framework and action situations. This process of translating phenomena into a formal language enables us to compare different cases and uncover regularities.

It is important to understand that the IAD framework is not a theory or a model. It does not suggest a hypothesis about how different parts of action situations relate to outcomes. Theory relevant to understanding social phenomena is an additional layer related to how people make decisions in different action situations.

Much of the discussion and the majority of examples focused on a particular context that we call coupled infrastructure systems. In those situations there are incentives for individuals to free ride on the cooperative actions of others. We experience social dilemmas in many action situations in our daily lives. For example, who is doing all the work in a group project, how do we pay for the highways we use, how do we make sure there is healthcare available when we need it, who writes the articles on Wikipedia, are our bridges being inspected for safety, who reduces their energy use to help reduce pollution?

How do we organize incentives such that we reduce free-riding in problems associated with issues we care about? One option is to use coercion. If people have a tendency to free-ride on the cooperative behavior of others, then privatization of common-pool resources and public goods is an option. The reasoning is that individuals will make better decisions regarding the use of private goods. We illustrated the problems associated with common-pool resources with an example in which multiple people share a meadow. Each individual has an incentive to add animals to the meadow and when everyone in the group does so, this will lead to overgrazing. If, on the other hand, everybody owns a part of the meadow, everybody will take care of their own property and won’t damage others’ property. Another policy might be to tax the use of resources, so that people will not overuse common-pool resources.

Both of these economic instruments (privatization and taxation) are used in managing shared resources in practice. However, these instruments face several practical limitations and are not the only options available. There are many examples of self-governance, meaning that the users and producers of the commons are crafting, implementing and maintaining the institutional arrangements themselves. Based on these institutional arrangements, communities can successfully govern the commons without privatization or taxation from an outside governmental body.

The challenge that the tools developed in this book are meant to address is to understand what kind of institutional arrangements are successful in which circumstances. A coercive approach is not necessarily a productive approach. Coercion may demotivate participants. Providing monetary incentives may also not always be beneficial. An illustrative example is a study by Gneezy and Rustichini (2000) on daycare centers. Parents often come late to collect their kids from daycare. To reduce the number of people who are late, an experiment was performed that imposed a monetary penalty when parents were late. Surprisingly, parents came late more often. Why should anyone complain when they have paid for it? Parents who were willing to pay the price could come late without feeling guilty. When the daycare centers wanted to revert back to the original situation and remove the penalty, the number of parents who came late remained high. A behavior that is a moral obligation (coming on time to collect your child) became an economic transaction (paying a fee). This is a risk of using economic incentives to stimulate behavioral change; it may have unintended, difficult-to-reverse consequences. That is, economic behavior may ‘crowd out’ moral behavior.

The study of successful institutional arrangements shows that it is important that participants in action situations are involved in the creation of rules, that there are low-cost conflict-resolution mechanisms, and that there are clear rules about who and when people can use the commons. Effective institutional mechanisms stimulate personal interactions that facilitate trust relationships and allow participants to build reputations. When people edit the English text of Wikipedia articles, they gain respect and a good reputation in the community that may enable them to occupy a special role in the community. When a tennis player, who just lost a match, shakes the hand of the opponent, it reinforces the respectful relationship they have with each other.

The emerging picture of effective institutional arrangements is that in order to be successful , it is important that people can develop trust relationships, gain a reputation, experiment with new arrangements, tolerate mistakes people make, and have commonly understood rules-in-use. Most of these insights have been derived from studies of communities who share common-pool resources. If we know so much about successes, why are there still so many problems?

17.2 Why are there still so many problems in governance?

In this book, we have discussed insights relating to the ability of communities to solve collective action problems. If we know so much about what leads to effective institutional arrangements, why are there still so many problems? What prevents us from successfully governing shared infrastructure systems?

More than a billion people around the world do not have sanitation or access to clean water. Many species go extinct each year and human activities cause long-term disruption to biogeochemical cycles in nature. Many of us waste hours each week in traffic jams and complain about the performance of elected officials.

Knowing what leads to better institutional arrangements will not solve all these problems. What are the main challenges? What are the open questions in our understanding of institutional arrangements that require further research? In the following paragraphs, we attempt to list some of the most important challenges. This list is not exhaustive but, rather, represents only a starting point.

One of the big challenges in our modern society is the scale of the problems we face. We are no longer living in small communities where we know exactly what everybody is doing. We may not even know who our neighbors are. In an increasingly urbanized world, we interact with many people who are strangers to us. Even so, there is still an incredible level of cooperation in most modern economies. A moment’s reflection should give the reader a sense of astonishment at the fact that hundreds of millions of people can effectively coordinate their behavior every day. How do we do this? Institutions are a big part of the story. We are able to signal to each other our reputation and trustworthiness because of the uniforms we wear (in the position of police officer, you must wear an official uniform), the tattoos we have, the certificates we have earned (positions defined by boundary rules) and the gossip that is spreading about us. It is not uncommon for us to give a stranger our credit card (backed by an enormous stock of institutions and organizations) to make a payment. We are accustomed to conditionally trusting strangers.

Nevertheless, the larger scale of our interaction spheres increases the possibility that we may lack the appropriate information to make good decisions. Think about people accepting the terms of home loans that they cannot understand. Think about large institutional investors who purchase investments for which they cannot assess the risks. The financial crisis of 2008 demonstrated just how calamitous and how much suffering such information failures may generate. There is also the possibility of misunderstandings about our intentions, motivations and the meaning of rules. An important condition of well-functioning institutional arrangements is that rules are commonly understood.

Being in larger groups makes it more difficult for individuals to be involved in rule crafting. In the position of a U.S. citizen of eighteen years or older, you may vote but you may also feel that your vote is insignificant. You may not be able to have an impact on the outcomes at the national level, but you still can participate in local governance issues whether this is through an elected office, community service project, or a volunteer activity for your children’s school. Individual actions in the community add up. Because the impact of such activities is difficult to measure, the incentives to take them are weak. This is one of the fundamental problems of society—the under-provision of public goods.

Further, larger groups will make it easier to be invisible as a free-rider. You can be one of the many who do not volunteer. Larger groups make it more likely that there are different opinions and more disagreement among the participants. Disagreement makes it easier not to act, even though we know we should.

How can we stimulate cooperation in large populations? Can we apply the insights from this book to an urbanized and globalized world? New technologies may provide solutions. Many of us have a mobile phone with us; a small computer that can register where we are and can be used to take photos and exchange information with friends in social networks. Can we use these devices to improve the information we have about each other in order to improve trust in relationships and monitor the actions of each other? How might this impact personal privacy? How we may be able to use the crowd to govern the crowd without impinging on privacy is an important, open question.

Another big challenge is that new problems always emerge. With every new technology there are benefits but there also come new problems. There was no cyber bullying before the Internet. It is more difficult to bully someone in person than virtually. There was no illegal downloading before digital recording. To illegally obtain a music recording 50 years ago, it was necessary to walk into a record store and walk out with a vinyl disc! Again, before the Internet, stealing was a more personal affair—you had to actually see the victim. Now it has become impersonal. New problems also emerge due to new insights from science. Improved technology allows better measurements and enables new discoveries, such as the emergence of the hole in the ozone layer. Our understanding of chlorofluorocarbons enabled us to determine that they were responsible. Reducing chlorofluorocarbons was fairly easy—the problem was clear, measurable, and well understood. The solution was technologically feasible and economical. This is in stark contrast to climate change, which poses a much more difficult collective action problem. If and when we develop global governance arrangements to deal with climate change, what will be the next problem to emerge? Will human society ever have enough time to solve its existing set of social dilemmas before being presented with another new problem? Or, put in another way, will humans ever learn to craft institutions and governance structures fast enough to address new challenges?

History suggests there are some reasons to be hopeful—e.g., the Montreal Protocol, which deals with chlorofluorocarbons—but the challenges are many. Globalization will bring with it global-scale problems. These will require global-level solutions. This will require cooperation between people from many different cultures. New mixtures of populations may require generations to develop commonly understood well-functioning regulations, slowing our capacity to respond. Further, because solving social problems is difficult and complex, people tend to stick with institutions that have worked in the past. The No Child Left Behind program is a good example. The tried and true solutions (based on the Protestant work ethic) of trying to create incentives for more discipline and harder work through higher standards and more measurement simply does not work for a public good like education today. Why? The social context is completely different and “education” is complex. In order to learn more material more quickly as the No Child Left Behind Act demanded, children need mentoring. In the past when parents had the time to mentor, No Child Left Behind may have been a great success (at least by its own measure of improved standardized test scores). At present, when in many households both parents work and have little time or energy to mentor their children, higher standards and more testing will have little effect (the No Child Left Behind Act was replaced in 2015 by the Every Student Succeeds Act due to bipartisan criticisms). Old solutions do not translate well to new situations and simple panaceas will fail. Rather, we must perform small scale experiments to get experience with new institutional arrangements in new contexts. Because such experiments are costly and require patience, developing effective institutions will require considerable collective will on the part of society.

The third challenge we face is that it is often not in everybody’s interest to solve a problem. Different people have different positions and interests. A problem for one participant can be an opportunity for another. Hence not everybody has an incentive to solve a problem. Problems don’t exist in a vacuum, there is already a social and ecological context for every problem we face. If the poor and unemployed don’t receive health care, it is not a direct benefit for those who have health care to pay for and share their health care benefits. The status quo, although not perfect, might be beneficial to many participants as compared to an alternative.

Finally, sometimes constitutional choice rules make it difficult to change a regulation. The European Union now consists of more than 25 nations. The EU employs an aggregation rule by which decisions are made by a unanimity vote. In a unanimity vote everybody needs to vote in favor in order for a proposal to be accepted. If the group is relatively small and people are sufficiently aligned in terms of their understanding and preferences, this will work. But in large groups, one individual country can take negotiations hostage to receive benefits for voting in favor of a motion.

17.3 Closing

In closing we can say that there have been significant developments over the past 50 years in our understanding of institutional arrangements and the way they structure social interactions. This book provides ways to study and analyze institutions. After reading this book, we hope you will view the problems we face everyday and the very diverse ways we are solving collective action problems through a new lens and in a different light.

Different disciplines contribute to our understanding of human behavior in the context of complex social and ecological systems. Unfortunately, we cannot provide a blueprint for how to solve all the problems we experience. Experimentation at the small scale and finding mechanisms to connect successful solutions to larger scales are key. Although we cannot provide simple solutions to complex problems, we have provided you with a powerful set of tools to make more informed decisions and recognize the importance of your own role in society.

17.4 Critical reflections

The rules and norms that govern human interactions can be studied with the framework that is presented in this book. The framework can be applied to many different topics including sustainability, health care, sports, education and the digital commons. Despite our increasing understanding of institutions and lessons regarding the conditions of successful collective action, there are still many failures.

Major challenges exist in governance in modern society since the scale at which we interact with others is much larger than it has ever been in human history. This makes lessons about success from studies of small groups difficult to apply. Furthermore, we experience misunderstandings if we don’t speak the same language or live in different social and ecological contexts. Finally, new problems are constantly emerging due to rapid environmental and technological change.

17.5 Make yourself think

1. How can you make a difference in addressing major problems in society?

2. Ask older family members how they made arrangements for going out (in a time before mobile phones and texting). Do you see changes in rules and norms?

3. What do you see as the most challenging topic of governance in the future?

17.6 References

Gneezy, U. and A. Rustichini (2000). A fine is a price. Journal of Legal Studies 29(1): 1–17.

Ostrom, E. (2005) Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.