4 Defining Institutions

Key Concepts

In this chapter we will:

- Learn how to define institutions and recognize them in everyday situations

- Learn to analyze institutions using action situations

- Become familiar with an overview of the institutional analysis and development framework, which will be used throughout this book

- Understand that incentives that impact decision-making can be studied using rigorous scientific methods

- Recognize the wide diversity of institutions in use around the world

4.1 Overview

There are many ways to induce people to contribute to provision and maintenance of shared infrastructure. Nudges and incentives such as rewards and punishment, shame and prestige might work in some localities but not in others. If village members in the hills of Nepal do not contribute to the maintenance of the shared irrigation system, the family cow can be confiscated and put on display in the center of the village. Since everyone recognizes the cow in these small communities, it is known to everyone that you are cheating the community. Other village members could milk the cow, until the offender paid a penalty. The cow jail works in rural Nepal but is unlikely to be effective in urban areas.

We will see that there are many different possible mechanisms that groups use to solve problems related to sustaining the commons. These different mechanisms, however, all rely on the same principles. Therefore, in this book, we will try to understand how people solve these problems by studying the basic principles contained in the institutions they use.

Broadly defined, institutions are the prescriptions that humans use to organize all forms of repetitive and structured interactions. This includes prescriptions used in households, schools, hospitals, companies, courts of law, etc. These prescriptions can function at different scales, from households to international treaties. These prescriptions can be one of two broad types: rules or norms. Because rules and norms are essentially human constructs, agreed-upon or recognized by a group of people, they are not immutable. That is, individuals can make choices whether or not to follow the rules or norms and these rules and norms can be changed. Importantly, their choices and actions have consequences for themselves and for others.

In the following chapters we will see that rules and norms are everywhere and define —sometimes literally, sometimes indirectly—how we live our lives. For example, rules and norms can affect who we marry, which schools we go to, which countries we enter, where we may sit on a bus, where we may park, who leads a discussion in a group, etc. Where do these rules and norms come from, and why do they differ in different countries and contexts? In this book, we are especially interested in answering this question for different types of shared infrastructure.

We will see that all of us can play a big role in defining rules and norms if we take the initiative to do so. Crafting rules and norms is not something that is undertaken exclusively by those in business suits in Washington, D.C. We ourselves create rules and norms too. For example, when you undertake a group project during a course, you will have to rely on some rules and norms. Some rules might come from the syllabus while others are created by you and the members of your group during your meetings.

In more abstract terms, the rules (or the absence of rules) in a particular situation affect who gets what benefits, who bears what costs, who is allowed to participate, and who gets what information. Further, the rules affecting one situation are themselves crafted by individuals interacting at higher levels. For example, the rules we use when playing basketball at lunchtime were themselves crafted by officials who have to follow such rules and norms to structure their deliberations and decisions.

This chapter provides a brief overview of the framework we will use in this book to study institutions.

In the following sections we will discuss these core questions:

- Why are there so many different types of institutions?

- How do we analyze institutions?

- What is the appropriate unit of analysis for studying institutions in general, and the commons in particular?

- How do we use one choice of an analytical unit, the action arena, to study institutions?

- What are the core components of an action arena?

2.2 Institutional diversity

During a typical day, we experience many situations in which we interact with others in a structured way where rules and norms may apply. This can be at work, in the classroom, on the sports field, in the supermarket, during commuting, when we bring our kids to daycare, when we watch a movie online, when we go to church, when we eat at the dinner table, etc. In all these different settings different types of norms and rules hold. At work you may have a formal contract regarding the duties that are expected from you and the compensation you are given for undertaking those duties. At the dinner table you may adopt some manners (which are the equivalent of norms) taught to you by your parents and relatives. In traffic you follow the norms and rules of the road. For example, one rule of the road is a speed limit. A norm is you don’t cut other drivers off when changing lanes. Can you tell the difference between a rule and a norm just based on these examples? Finally, we interact with many strangers every day whom we expect to follow the same rules.

When you start realizing the number of rules and norms we implicitly deal with on a daily basis, it might become overwhelming. But most of us are easily able to participate in all these diverse sets of situations without thinking too much about the rules and norms that structure them or specific decisions we make in those situations. Several scholars have explored the question of what enables us to do this. Not only are we faced with many different situations each day, the situations we can experience change over the generations. It is likely that today we experience more different types of situations at different levels of social organization as compared to previous generations. People living in a small village in Europe in 1200 AD were not thinking about the implications that political developments in China might have on their lives.

We now expect to communicate with our relatives or be able to check on the latest news wherever we are in the world. Our meals are not restricted by the seasonal availability of foods produced by local farmers. We transport ingredients for our meals from all over the world (e.g., tropical fruits and vegetables in the winter in New England) at considerable environmental costs. Such changes are not just caused by technological developments, but also through changes in institutions. To make sure fruits and vegetables are transported reliably from location A to B, we have to create institutions to structure repetitive interactions between all the individuals involved. Without institutions, the transaction costs for exchanges between farmers, transporters, and retailers would make long distance transport of food extremely costly.

It is obvious to us what to do when we are shopping in a supermarket. We take the items we prefer from the shelves. We then “arrange a meeting with the cashier,” which is made easy by check-out lines and the norms for standing in lines (standing in lines is not a norm everywhere!). The cashier knows we wish to have a meeting by virtue of the fact that we are standing in line – they do not have to ask us why we have come to meet them. We then engage in an exchange with the cashier. What exactly do we exchange with the cashier? Do we exchange food? No—the cashier does not own the food. We exchange information. We may give the cashier a piece of plastic with information on it (a credit card) or we may use cash—which is also a form of information about value and obligation. But this strategy does not work everywhere. When we are shopping in an open bazaar in Asia or Africa, we may bargain over the price of the fruit that is left on the stand at the end of the day. Such bargaining to get a lower price is also happening for other goods in a bazaar. In fact, not bargaining (i.e., not adopting a local norm) for a lower price would be a clear indication that you were a stranger and that you do not know what to do in this situation. This may drastically affect the price of the goods. In this case, in contrast to the grocery store example, the seller may actually own the fruit and thus will be exchanging goods with you. Further, more information is exchanged. In the grocery store example, we believe, or at least accept if we are not willing to shop around at different grocery stores, that the “market” provides information about the correct value of a given item. In the bazaar, haggling over price “reveals” supply and demand prices which, through a very local market interaction (between just two people) drives the price to the ‘market clearing equilibrium price’. Anyone who has haggled over prices can attest extracting this information can be a quite costly in terms of your time. Finally, once the supply and demand prices converge, what will you be exchanging for the goods? Probably not a number and an expiration date on a piece of plastic!

Can you use U.S. dollars, say in Africa? Maybe, maybe not. These examples illustrate that there are many (subtle) changes from one situation to another even though many variables are the same. These subtle changes can have major consequences for the interactions between people.

The types of institutional and cultural factors we have been discussing affect our expectations regarding the behavior of others and their expectations regarding our behavior. For example, once we learn the technical skills associated with driving a car, driving in Phoenix (Arizona) or Bloomington (Indiana)—where everyone drives fast but generally follows traffic rules—is quite a different experience from driving in Rome, Rio de Janeiro, and even in Washington, D.C., where drivers appear to be playing a game of chicken with one another at intersections rather than following traffic rules. Driving in India can seem like a life-threatening experience. Nobody seems to follow traffic rules but there are clear norms such as “the cows are free to go wherever they want, including highways,” or “honk when you drive behind somebody so they know,” and “expect the unexpected.” When playing racquetball with a colleague, it is usually okay to be aggressive to try to win by using all of one’s skills. On the other hand, when teaching a young family member how to play racquetball, the challenge is how to help them have fun while they learn a new skill. Being too aggressive in this setting—or in many other seemingly competitive situations—may be counterproductive. A “well-adjusted and productive” adult adjusts their expectations and ways of interacting with others to “fit” a wide range of different situations. Such adjustments are often second nature.

Although we may not explicitly realize it, we have a lot of implicit knowledge of expected dos and don’ts in a variety of situations. Frequently, we are not even conscious of all of the rules, norms, and strategies we follow. Nor have the social sciences developed adequate tools to help us translate our implicit knowledge into a consistently explicit theory of human behavior. In most university courses students learn the language of a particular discipline, from anthropology to economics, from psychology to political science, etc. This disciplinary narrowing of language may hinder our understanding of how to analyze the diverse sets of situations we encounter is social life. The framework we discuss in this book may provide a common language to study these different situations.

4.3 How to analyze institutions?

There are millions of different species on our planet that interact in complex ways at different spatial and temporal scales. How does one study such complexity? One of the breakthroughs in biology is the concept of genes and the discovery of DNA, the building blocks of the diversity of life forms on Earth. Can we develop an equivalent set of concepts for building blocks that create institutions?

If the situations in which people experience different norms and rules are so diverse, how can we study them? How can we make sense out of such social complexity? Given that there is such a large variety of regularized social interactions in markets, hierarchies, families, legislatures, elections, and other situations, is it even possible to find a common terminology to study them? If so, what framework could we use to analyze these different situations across different cultures? Can we learn from one type of institutional arrangement for a particular context and apply the lessons to another context?

Can we identify attributes of the context in which people carry out their repeated interactions in order to find communalities that distinguish success stories from failures? If we are successful with this, we may be able to explain behavior in a diversity of situations varying from markets and universities to religious groups and urban governance. This analysis of interactions among people may take place at a range of levels from the local to the global, and we may analyze whether processes occurring at the local level may explain some of the challenges at the global level.

These are all very ambitious goals. However, as you will see from the material in this book and associated coursework, the framework that we will discuss will help to provide us with a much better understanding of key features that appear throughout a diverse set of situations. The framework is an outcome of many studies conducted at the Vincent and Elinor Ostrom Workshop of Political Theory and Policy Analysis at Indiana University, which was created in 1973 by Vincent and Elinor Ostrom (Figure 4.3). Many of their colleagues all over the world have contributed to this framework by testing it on diverse sets of problems.

In the rest of this chapter we will provide a brief overview of the basics of the framework. The framework is called the Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework. One of the aspects of social systems that makes the IAD framework complex is the existence of different types of regularized social behaviors that occur at multiple levels of organization. There is no simple theory that predicts everything, and therefore we need to understand what kind of behavior is to be expected in each type of context.

4.4 Action arenas and institutional analysis

An action arena occurs whenever individuals interact, exchange goods, or solve problems. Some examples are teaching a class, playing a baseball game, and having dinner.

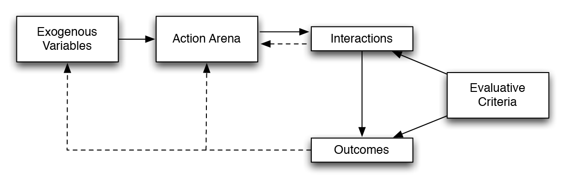

When two people exchange a product on eBay, they are in an action arena. This is an example of the focal level of analysis we use throughout this book. In an action arena, participants, rules and norms, and attributes of the physical world come together. The latter two elements, the rules and norms and the physical world are said to define an action situation. Action situations remain stable over time relative to the participants who may take part. For example, the eBay action situation does not change over the course of a day during which millions of participants can enter the action situation and generate an action arena. As participants interact in the action arena, they are affected by exogenous variables and produce outcomes that, in turn, affect the participants and the action situation. Exogenous variables are those whose characteristics (values or probabilistic distributions) change much more slowly than the relevant time-scale of the action arena. Specifically, actions may change in an action arena in the timespan of minutes or seconds whereas norms may take generations to change. Action situations exist in homes, neighborhoods, regional councils, national congress, community forests, city parks, international assemblies, and in firms and markets as well as in the interactions among all of these situations. The simplest and most aggregated way of representing any of these arenas when they are the focal level of analysis is shown in Figure 4.4., where exogenous variables affect the structure of an action arena, generating interactions that produce outcomes. Evaluative criteria are used to judge the performance of the system by examining the patterns of interactions and outcomes.

Let’s discuss some examples. Consider two participants: John and Alice. When John and Alice play a game of chess, the action situation is composed of (a) the physical game of chess including the board with 64 squares and the pieces: 8 black and 8 white pawns, 2 black and 2 white rooks, 2 black and 2 white knights, 2 black and 2 white bishops, 1 white and 1 black queen and 1 white and 1 black king along with the context in which the chess game is located, i.e. is it at a picnic table outside, a dim room, a cold room, etc.; and (b) the rules of chess—how each piece can be moved, how pieces interact, and what constitutes a victory. When John and Alice sit down at the chessboard to play, this forms an action arena. The interactions between the players may lead to either John or Alice winning the game or a tie. Hence the outcome is whether the game is won by one of them or whether it was a tie. The same persons may also be in an action arena involving money lending. In this action arena, the action situation may be less structured than the chess game. Consider the action arena in which Alice lends money to John. Suppose Alice and John are good friends and the amount of money is small. Alice gives the money to John who agrees to return the money at some specified date (often rather vague in such situations). In this case, the action situation is simple: it is defined by the shared norms of informal money lending and shared understandings of trust and trustworthiness in Alice’s and John’s culture. Suppose, on the other hand, that this exchange is performed in a formal way. Another participant enters the action arena, a notary public, who formulates a contract that is signed by Alice and John. In this case, the action situation is slightly more complex as it involves a formal contract legitimized by the legal infrastructure in the jurisdiction where the contract is drawn up, the notary’s presence, and the signatures of Alice and John. Now the formal rules of contract law, the testimony of a third party recognized by the state (notary) who will testify to the identity of the signatories of a contract, and an entity that will archive the contract form the action situation. The outcome of this transaction is that John receives the money and pays it back according to the conditions as stated in the contract. A third party enforcer ensures that the conditions of the contract are met. A third possible action arena would be an election. Alice and John are both candidates for president of the student association. Within the action arena participants include all the students of the association who are allowed to vote for one of the candidates. The interactions include debates, a campaign, and finally the election day in which a winner is decided. The evaluation criteria stipulates that the winner is determined based on which candidate has a simple majority (i.e., more than 50%) of the votes. In the last example, Alice and John are neighbors who have a conflict about the barking of Alice’s dog. The action situation is a conflict. Within the action arena we have Alice, the dog, John, and the local authorities whom John calls to intervene. Alice and John may both hire lawyers to represent themselves when the action situation (conflict) is played out in court. The interactions include the daily occurrences of the dog barking, the initial friendly requests of John to silence the dog, and the escalation of the conflict into a court case. There are various possible outcomes: either John or Alice moves out of the neighborhood, the dog gets training to stop barking, the dog is sold, John gets a financial compensation for the inconvenience, etc. Each outcome is evaluated differently by each of the participants, including the lawyers. For example, if John’s lawyer gets a certain percentage of the financial compensation, she may focus on winning a case to get that financial compensation, although this may lead to long-term bad relations between Alice and John.

Outcomes feedback into the participants in the action arena (the dashed arrow from outcomes to the action arena in Figure 4.4. For example, the fact that a player loses a chess game affects her next decision regarding the action situation of playing chess (play another game or not). The dog continuing to bark after one interaction (John asks Alice to quiet the dog) will undoubtedly affect John’s next decision. This changed view by one or several participants may induce the action situation to transform over time as well. Over time, outcomes may also slowly affect some of the exogenous variables. For example, decisions people make regarding energy use creates outcomes including emissions of CO2 which in the long term affect the climate system. In a world with a changed climate the costs and benefits of various human activities are affected, which will affect action arenas. In undertaking an analysis, however, one treats the exogenous variables as fixed—at least for the purpose of the analysis.

When the interactions yielding outcomes are productive for those involved, the participants may increase their commitment to maintaining the structure of the situation as it is, so as to continue to experience positive outcomes. For example, wealthy people who may have benefited from low taxes in the past may support tax cuts that the Bush administration introduced. However, if participants view interactions as unfair or otherwise inappropriate, they may change their strategies even when they are receiving positive outcomes from the situation. For example, a group of millionaires requested that President Obama raise taxes for wealthy people.

When current outcomes are perceived by those involved (or others) as less desirable than other outcomes that might be obtained, some participants will raise questions about particular action situations and attempt to change them. But rather than trying to change the structure of those action situations directly, they may move to a different level and attempt to change the exogenous variables. The Occupy Wallstreet movement of 2011 was a protest against the perceived unfairness in society due to a culture of greed by bankers and other participants who control the financial system. The protesters requested a change of the financial system (the exogenous variable) in order to move toward a more equitable society in which they may also succeed (a different outcome). But they didn’t try to change the banking system directly. They tried to affect the exogenous variables, for example, the perception of the general public toward the actions of banks.

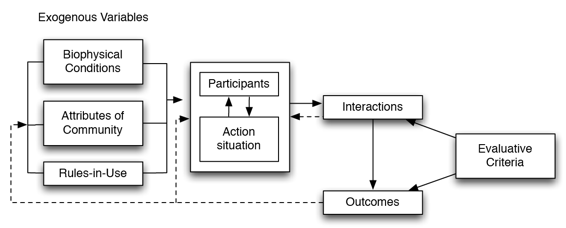

Figure 4.4 is the simplest schematic representation of an action arena. As you see from the example, there are many important layers to each action arena. We unpack this simple representation in Figure 4.5 in order to make these layers more apparent. An action arena refers to the social space where participants with diverse preferences interact, exchange goods and services, play a game, solve problems, have an argument, receive and deliver health care, etc. We make a distinction between an action situation and an action arena to emphasize that the same participants can fill different roles in different action arenas as we saw with John and Alice. The action situation refers to the positions, actions, outcomes, information and control that provide the structure by which participants interact. Thus the action situation provides the institutional context with which the participants in an action arena are confronted. In Chapter 5, we will zoom in and unpack the action arena. Let’s look at a broader overview of the IAD conceptual map.

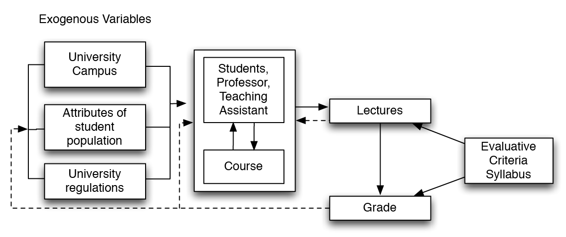

Let’s apply the framework to a concrete example, namely the course you are taking for which you are reading this book (Figure 4.5). The action situation is defined by the general rules about taking a course at your university (grades, credits, conduct) further specified by the syllabus for this particular course and the characteristics of the space in which the participants meet. Taking this course (along with all the other students) then constitutes an action arena. In the action arena there are a number of different participants, namely the students, the professor and the teaching assistant. The participants interact via lectures, taking exams and writing essays. The syllabus of the course specifies what is needed to receive a good grade in the course. It specifies the weight of the different types of interactions, from participation in class, giving a talk, writing an essay and taking an exam. For each of these activities there are more detailed evaluation criteria on how to receive a good exam grade or writing the essay. The final outcome of the course is a grade.

The exogenous variables in which these interactions take place are the facilities of the university campus (the quality of the classrooms, computer commons, etc.), the attributes of the students (what criteria is required to be admitted to the university, quality of other courses, etc.), and the university regulations. These are specific examples of the general categories of exogenous variables in Figure 4.5: The biophysical conditions, the attributes of the community, and the rules in use, respectively.

Although the final grade is mentioned here as the outcome of the course, this can be debated. If this were truly the only outcome we cared about, the participants could agree (e.g., all vote to give each other an A) that the students could all get an A without putting in the effort of taking the course. Obviously, this is not the purpose of a course and is a violation of university regulations. Although the focus of many participants in the action situation might be on the grade, there are other outcomes that we may include. Does the course material lead to new insights and useful experiences for the students? Do the students comprehend the material and can the students apply this to other topics or problems they may encounter in life? Is the atmosphere in the classroom pleasant and productive? These kinds of outcomes are more difficult and costly to quantify, but are nonetheless very important. However, the difficulty with measuring such outcomes might be a reason that officials may choose to focus on grades to measure course outcomes.

4.5 Context of the action arena

The action arena does not occur in a vacuum. Participants are interacting in an action situation which is affected by a broader context. As mentioned above, this broader context is defined by three clusters: (1) the rules used by participants to order their relationships, (2) the biophysical world that are acted upon in these arenas, and (3) the structure of the more general community within which any particular arena is placed.

Different scholarly disciplines focus on different clusters. Anthropologists and sociologists may focus more on the role of the community and culture while economists focus more on how rules affect the incentives of the participants. Environmental scientists may focus more on the biophysical attributes of the action arena. In this book, we focus on the rules, but take into account the role of the community and the biophysical environment.

Rules

Many of the readers of this book are used to an open and democratic governance system where there are many ways in which rules are created. Under these conditions, it is not illegal or improper for individuals to self-organize and craft their own rules for many activities. This may be in stark contrast to more dictatorial states in the world. At work, in a family, or in a community organization there are many ways we experience the crafting of rules to improve the outcomes we can expect in the future. Some of these rules are written down on paper, others are verbal and may be confirmed by a handshake.

In our analysis of case studies in this book, we make a distinction between rules-on-paper (de jure) and rules-in-use (de facto). It is not uncommon that in practice, somewhat different rules are used at the work floor, in the classroom, or on the sports field than those officially written down on paper. For example, a referee in a soccer match may not stop the game for each possible rule infraction, but judge whether the infraction is severe enough to stop the flow of the game and enforce penalties.

Human behavior, including the tendency of humans to comply with rules, relies on the extraordinarily complex structure of neural networks in our brains and, as a result, is not as predictable as most other biological or physical phenomena. Humans are reflexive and have opinions and moral values. They may not necessarily obey instructions from others. All rules are formulated in human language. As such, rules might not always be crisp and clear, and there is a potential for misunderstanding that typifies any language-based phenomenon. Words are always simpler than the phenomenon to which they refer. In many office jobs, for example, the rules require an employee to work a specified number of hours per week. How accurately do we need to specify what the employee will be doing? If the employee is physically at her desk for the required number of hours, is daydreaming about a future vacation or preparing a grocery list for a shopping trip on the way home within the rules? Written rules are always incomplete and therefore the very act of interpreting the rules may lead to different outcomes. Monitoring rule compliance is a challenging activity if rules are not always clear and fully understood. Thus, when we study an action arena, we will look not only at the official rules on paper, but also the rules in use. Misinterpretations may lead to differences between the two. For good performance of institutional arrangements, it is important that the rules are mutually understood.

The effectiveness of a set of rules depends on the shared meaning assigned to words used to formulate them. If no shared meaning exists when a rule is formulated, confusion will exist about what actions are required, permitted, or forbidden. The effectiveness of rules is also dependent upon enforcement. If rules are perfectly enforced then rules simply say what individuals, must, must not, or may do. Participants in an action arena always have the option to break rules, but there is a risk of being caught and penalized. Has the reader ever driven faster than the official speed limit? If the risk is low, rule breaking might be common. Further, because of the feedbacks in action arenas, the likelihood of rule breaking can grow over time. If one person cheated without being caught, others may follow and the level of cheating will increase. This will increase the detection of cheating behavior and more rigorous rule enforcement might be implemented. If the risk of exposure and sanctioning is high, participants can expect that others will make choices from within the set of permitted and required actions.

One of the main benefits that accrue to participants when the majority of people follow the rules is the increased predictability of interactions. Virtually all drivers in the U.S. use the right side of the road to drive almost all the time. If such a rule were not obeyed frequently, imagine how difficult it would be to drive and how ineffective it would be to use the road. Knowing what to expect in interactions with others vastly improves the performance of many social systems.

Biophysical conditions

As we will see throughout the book, the rules affect all the different aspects of the action arena. The biophysical world also has an important impact on the action arena. What actions are physically possible, what outcomes can be produced, how actions are linked to outcomes, and what actors can observe are all strongly affected by the environment around any given action situation. For example, water can’t run up hill. Once you say something, you can’t retract it. The same set of rules may yield entirely different types of action arenas depending upon the context. For example in New York city there is regulation that residents of buildings are responsible for removing the snow on sidewalks in front of those buildings within four hours after the snow ceased to fall. Why does Phoenix not have such a regulation? We will discuss many case studies in different application domains in this book that will help recognize how context affects decision making and the effectiveness of rule configurations.

The recent COVID-19 pandemic impacted the biophysical conditions in many action arenas. Teaching via Zoom is not the same as in person, and it is expected that the learning outcomes for many students is lower than it would have been in an in-person classroom. However, for some students, online learning works well, and as such it is important to evaluate when what kind of intervention leads to desirable outcomes.

Attributes of the community

A third set of variables that affects the structure of an action arena relate to the attributes of the community of which the participants are members. Examples of attributes that might be important are the shared values within the community, the common understanding and mental models that the community members hold about the world in which they live, the heterogeneity of positions within the community such as class and caste systems, the size of the community, and the distribution of basic assets within the community.

The term culture is frequently applied to the values shared within a community. Culture affects the mental models and understanding that participants in an action arena may share. Differences in mental models affect the capacity of groups to solve problems. For example, when all participants share a common set of values and interact with one another frequently, it is more likely that the participants will be able to craft adequate rules and norms for an action arena. If the participants have different mental models, come from different cultures, speak different languages, have different religions, it will become much harder to craft effective institutional arrangements.

4.6 Critical reflections

Institutions are rules and norms that structure human interactions. They are complex and difficult to study. The Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework helps us organize our thoughts and direct our questions. The focal element of the IAD framework is the action arena in which participants interact in an action situation. These interactions lead to outcomes which affect decisions made in the next iteration. The interactions are affected by the social and biophysical context in which the action situation takes place.

4.7 Make yourself think

1. Come up with institutions you deal with every day, some you don’t like and some that you do like.

2. Do you think banks should be regulated in their lending practices? What are the key elements necessary to address this question?

3. What is the most important outcome for you in taking this class?

4. What can explain the fact that people solve problems differently in India as compared to the U.S.?

4.8 References

-

Ostrom, E. (2005) Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.