1 The Challenges We Face

Key Concepts

In this chapter we will:

- Discuss the broad challenges humanity is facing

- Define the meaning of the term “commons” as it relates to modern social challenges

- Provide examples and a critique of the “tragedy of the commons” concept

1.1 Living in the Anthropocene

We live in interesting times. Humanity is causing such an impact on the functioning of Planet Earth that we have even started referring to recent times a new geological era, the Anthropocene. Human activities have caused such a wide and deep impact on the ecological and biochemical processes on Earth that the climate is changing, coral reefs are bleaching, the forests are on fire, the oceans turn to acid, the permafrost is melting, and groundwater levels are declining. These changes are caused by extracting huge amounts of minerals and biomass for our own energy, food, and material consumption and dumping it after use in concentrated forms in the wrong places in the Earth’s biogeochemical cycles.

Humanity has experienced an unusually stable climate during the last 10,000 years which has enabled us to create complex societies. From hunter-gatherers, we transitioned to sedentary agricultural societies. We have major social and technological achievements to show for our skill at extracting resources from the biosphere through agriculture. We put humans on the Moon, controlled nuclear reactions to generate power, decoded DNA, created art, iPhones, beautiful architecture, global supply chains, and relatively peaceful life together at very high density among genetically unrelated individuals in large cities. But, the accumulation of disturbances caused by those complex societies will make the environment more unpredictable, impacting the way we can produce food, use energy, and find shelter. We can expect more frequent major storms, forest fires, heat waves, landslides, and more salinity of dry lands. Besides the environmental challenges, we are also experiencing increasing inequality in wealth within and between countries. The increased population densities in an urbanized world makes us more prone to infectious diseases, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, and increased resource scarcity to maintain our highly materialistic way of life is causing conflicts within and between countries.

How did we get here and how can we cope with these changes? In this textbook, we will discuss some of the fundamental dynamics behind these changes we observe. Building on principles from the social and life sciences as well as engineering, we present an integrated framework, the coupled infrastructure systems framework, that can be used to analyze complex problems. Because we use a common framework to look at many systems around the world, we also have developed an understanding of what leads to sustainable outcomes, and what is more likely to fail.

The coupled infrastructure systems framework originated in the study of the commons, and provides a broader perspective on applying the lessons learned from the extensive literature on governing the ecological/biological commons to other similar resources.

In the rest of this chapter, we will focus on ‘the commons dilemma’, one of the fundamental challenges that must be overcome to achieve the sustainable use of natural resources. The next chapter will translate this to a broader set of collective action problems, namely around any type of shared infrastructure, and in chapter 3 we continue with a discussion on the governance challenges we face.

1.2 What are the commons?

The original meaning of the term “commons” comes from the way that communities managed shared land in Medieval Europe. This shared land was not owned by any single individual but, rather, was “held in common,” by a community, usually a village, thus the term “commons.” Along with this shared land was a clear set of rules developed by the community about how it was to be used. Technically, the term “commons” thus refers to the land and the rules that go with it to govern its use. Over time, the term commons has taken on several meanings. Most generally it can be used to refer to a broad set of resources, natural and cultural, that are shared by many people. Examples of resources that are referred to as “commons” include forests, fisheries, or groundwater resources that are accessible to members of the community. The key term here is “shared.” Forests, for example, need not be shared—there are many examples of private forests. Thus, implicit in the term “commons” as it is frequently used today is that there are no property rights established over the resource. That is, the resource is “open access.” This departs somewhat from the original meaning and has, unfortunately, caused some confusion as we shall see later. Other examples of commons that the reader will encounter in everyday life include open source software, Wikipedia, public roads, and public education. Throughout this book, we will use the term “commons” to refer to a resource, or collection of resources over which private property rights have not been established.

Regardless of how they are managed, these examples show that the types of resources that can be defined as “commons” are essential for our societies. We share them, inherit them from previous generations, and create them for future generations. The commons are therefore crucial for our wealth and happiness. Those commons are an example of collective action problems, which are situations where there is a conflict between the interest of the individual and the interest of a group. Collective action, such as coordination and cooperation, is needed to achieve collective outcomes.

Why would we care to study the commons? In this chapter, we will explain that there is a big challenge associated with sustaining the commons. Because of the lack of clear rules of use and mechanisms to monitor and enforce those rules, many commons are overharvested. Examples include fishers fishing the oceans in international waters, farmers pumping up groundwater, or movie watchers using the limited bandwidth of the community internet connection, reducing data availability for other users. How can we make sure that the commons are used wisely and fairly? Who should regulate the use of the commons? Who should make the rules? In the original commons in Medieval Europe, the answer to these questions was clear: the community that held the land in common made the rules and enforced them to regulate the use of the commons. In modern commons, where the resources in question are typically much more complex, answering these questions is much more difficult.

When we, the authors of the book, were teaching a course in Beijing, we had to walk on the streets wearing masks to protect ourselves from air pollution. This experience is a powerful reminder that the air we breathe is part of a commons. As individuals, we have no control over the pollution in the air and, as a result, of the quality of the air we breathe because there are no comprehensive property rights governing access to the atmosphere. In some cities, the air quality is dangerously bad, while in others the sky is blue and there are no measurable pollutants. What underlies these differences? Is this due to regulation, population density, or the geography of the landscape? What are the costs and benefits of improving air quality and who will lose and who will gain from such changes? Who is making the decisions on activities that affect air quality? So the type of question that is of interest to people who study the commons is “what enables some groups to successfully resolve commons problems and what prevents others from doing so?”

There are many successes and failures regarding governing the commons. We will introduce a framework that can be used to help us analyze the various types of commons that are so important to our well being and illustrate how it can be used to provide a better understanding of how to better govern our shared resources. There is no silver bullet solution that will always lead to the outcomes we desire, but we can learn about mechanisms that increase the likelihood of achieving desirable outcomes.

How to effectively govern the commons has been a long debate in academia. Over the last 50 years, the traditional approaches to solving the commons problem through privatization or state regulation have been challenged. The next section will introduce the basic elements of the debate, the controversy that has arisen around it, and some alternative solutions.

1.3 The tragedy

In 1968, biologist Garrett Hardin (Figure 1.1) wrote a famous essay in the journal Science titled “The Tragedy of the Commons.” Garrett Hardin was an American ecologist who warned of the dangers that the increasing human population would impose on the environment. He argued that when people share a resource they will overharvest it because it is in their individual interest to take as much as possible.

Hardin used the metaphor of sheepherders sharing an open-access pasture. He erroneously referred to this open-access shared resource as a “commons” (if it were really a commons the community would use a common-property governance regime to regulate access—more on this later). The title of his paper should have been “The Tragedy of Open-Access.” Unfortunately, this use of the term “commons” stuck and, in fact, has had unfortunate consequences, as we will see shortly. Because there are no restrictions on the use of the pasture, each herder can benefit as an individual by adding extra sheep. Unfortunately, if all the herders add sheep, as a group they will eventually bear the costs of the additional grazing, especially when it creates a situation in which the total number of grazing animals consumes grass faster than the pasture can regenerate new grass. The effect of overgrazing is shared by all herders, but the benefit of adding extra sheep goes to the sole owner of the sheep (as long as other herders do not add too many sheep).

Based on the reasoning that people are rational selfish actors, any time the benefits of using a shared resource are private and the costs are shared, we can expect the commons will be overgrazed. Hardin formulates this as follows:

Therein is the tragedy. Each man is locked into a system that compels him to increase his herd without limit – in a world that is limited. Ruin is the destination toward which all men rush, each pursuing his own best interest in a society that believes in the freedom of the commons. Freedom in a commons brings ruin to all (Hardin, 1968 p. 1245).

The observation that people cause problems for the common good when they follow their self-interest is not new. The Greek philosopher Aristotle noted more than 2000 years ago that “what is common to the greatest number has the least care bestowed upon it.” The reason that Hardin’s argument got so much attention was due to his recognition that the concept can be applied to many modern environmental problems. With the emerging interest in environmental conservation in the 1960s, he provided an explanation for why we were causing so much damage to the environment.

Hardin concluded that there were only two options to avoid the depletion of the commons. One option was to give the herders private property rights. If each herder owned a piece of the common land and the herder’s sheep caused overgrazing and erosion, the costs would be felt by the individual herder only. For this reason, the rational herder would choose to put an appropriate number of sheep to graze on the land in order to maximize her long-term earnings. The other possible option is for a government body to restrict the amount of grass that can be consumed. However, in order to enforce the restriction, the government would have to monitor the amount of grass consumed by each herder—a costly exercise. An alternative would be for the government to require that herders pay a tax per head of sheep, which the government would use to hire a guard to monitor whether the herders follow the rules.

The importance of Hardin’s argument is its conclusion that people are not able to self-govern common resources. That is why he calls it a tragedy. The fact that Hardin focused on this inevitable tragedy is perhaps related to his use of the term “commons.” In fact, in traditional contexts there was no “freedom in a commons”—a commons always had a set of rules associated with its use, and these rules did not necessarily include either of Hardin’s two options. Unfortunately, Hardin’s judgment has been widely accepted due to its consistency with predictions from traditional economic sciences and increasing numbers of examples of depletion of environmental resources. What this judgment fails to take into account are the many cases of successfully managed commons in which the shared resource is used sustainably. That is, there are many cases where a “tragedy of the commons” has been averted without privatization or state control.

The consequences of this work were significant. Hardin and others did distinguish three types of property rights: communal, private, and state. However, they equate communal property with the absence of exclusive and effective rights and thus with an inability to govern the commons. Experience does not bear this definition out: communal property, or common-property governance regimes do provide exclusive and effective rights, which are often used to govern the commons. From Hardin’s perspective, which neglected this third governance regime, sustainable use of shared resources without the state or private property was only possible when there was little demand or a low population density.

Garrett Hardin provided a compelling explanation for the emerging environmental movement in the 1960s. There was an increasing awareness of the decline of natural resources due to human activities, including the perceived scarcity of raw material; deforestation; overfishing; as well as increasing levels of water and air pollution, leading to smog and acid rain as well as health problems for human populations.

A few years after the publication of Hardin’s article, the first oil crisis took place which led to a rapid increase in oil prices. This shock generated the perception that oil was becoming scarce and that we were overusing our shared resources. Hardin’s paper provided a simple analysis and a simple solution. Assuming people make rational decisions, the implications for policy were clear. To avoid overexploitation of resources shared in common it was critical for the state to either 1) establish, monitor, and enforce private property rights or 2) directly regulate the use of the commons either by taxing or directly restricting (e.g., licensing) its use.

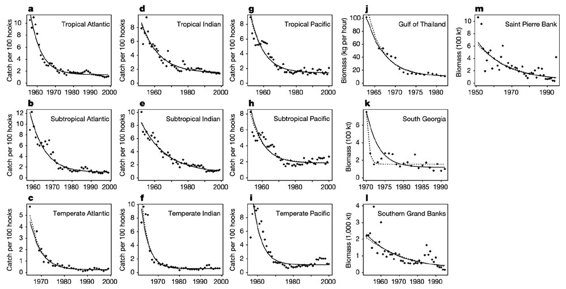

Figure 1.2 shows the decline of the stock of predatory species in the world’s oceans over a 40–50 year period during the second half of the 20th century (Myers & Worm, 2003). Since the 1968 essay, policies have changed, yet we haven’t seen a reversal of the overall trends. The fish stocks in Figure 1.3 still have not started to recover even after the institution of many new fishing policies since the early 1970s. Moreover, we are now beginning to experience new environmental commons problems, like the loss of biodiversity and climate change, despite efforts by nations to draft international treaties to regulate these “global commons.”

As we have hinted above, we will show in this book why Hardin’s analysis was limited. Although we see resource collapses around the world (tragedies of open access), we also see many success stories of long-lasting governance of shared resources (triumphs of the commons). Open access situations are not always tragedies. Many times common-property management regimes fail, as do private property and state-centric regulatory governance regimes. There are no panaceas. The goal of this book is to illustrate a set of tools that can be used to determine what conditions make overexploitation more likely and what conditions are more likely to lead to the sustainable use of shared resources.

1.4 The common pasture of Hardin

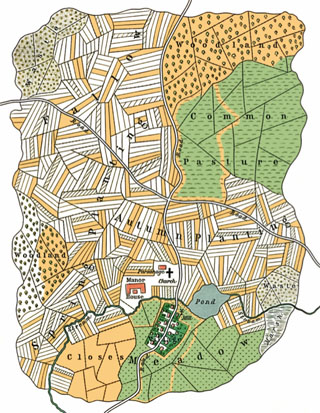

As we mentioned above, in his description of the “commons,” Garrett Hardin implicitly assumed open access to the pasture. The example Hardin gave was grazing on common land in Medieval Europe. Let’s look at the actual situation of the medieval open-field system in Europe, especially in England, in more detail (Figure 1.3).

In the open-field system, peasants had private property rights to the grain they grew on multiple small strips of land that were scattered around a central village. However, during particular seasons, peasants were obligated to throw the land open to all the landowners in a particular village so that they could all graze their sheep on the common land under the supervision of one herdsman. The decision to convert the strips of privately used land into shared land for a period during each year was made by a village council. This enabled people to take advantage of economies-of-scale in grazing (as well as providing manure for their land) and private incentives in grain-growing (which lacks important economics of scale and suffers from free-riding when communal groups try to share labor inputs. This is an example of a social dilemma, a topic we will discuss in Chapter 3.

The purpose for scattering small strips of land has been debated among scholars, as the benefits of the two scales could be achieved with or without the scattering of the agricultural land. Further, the scattering of land appears to have been an inefficient system, given that a single farmer had to divide his time between multiple, small agricultural strips rather than being able to economize on his own time and focus on one piece of land. Some scholars argue that the need to share risk due to different soil and precipitation patterns may have been a contributing factor. Others argue that by not allowing anyone farmer to gain a large amount of contiguous land, the village avoided creating a situation of asymmetric bargaining power. No farmer-owned enough land to be able to “hold out” from the commons and graze his own animals on his own land. Nor did an individual have a right to exclude others once the village decided the land should be converted from agriculture to pasture. If all of the farmers had owned sizable chunks of agricultural land in “fee simple” (a form of private ownership in England), rather than the village being responsible for land-allocation decisions, transaction costs would be very high.

If the argument that the commons were managed effectively in the open-field system has some validity, why did the open-field system disappear? And why did it take such a long time for it to disappear across most of Northern Europe? If private property alone was a very efficient solution to the production of food, once a particular location discovered this efficient solution, one would expect to see a change occur rapidly throughout Europe. The explanation might relate to transportation costs. Due to high transportation costs, local communities needed to produce both meat and grain in a small local area for their own consumption. This was only feasible if they could convert agricultural land to a common pasture when the crops had been harvested. When transportation networks improved and communities gained access to markets in grain and meat, there was no longer a need to continue with this complicated adaptation. Communities could specialize in meat or grain. Interestingly, this shift was facilitated by the development of a new “commons,” i.e., the shared resource of the public transportation system.

Thus, as we mentioned above, the medieval commons used by Hardin in his metaphor were, in reality, not open access. The commoners had crafted effective norms and rules to govern their shared pasture and to avoid overexploitation. Moreover, there are many implicit rules involved in the use of the commons. For example, a herd of livestock is the private property of the farmers, but the grass they consume does not become private until the animal swallows it. Could farmers directly harvest the grass for their livestock? A farmer who does so will likely get in trouble as there might be informal rules that grass can only be harvested via the livestock.

This simple example of a shared pasture with grazing sheep illustrates how common-property governance typically involves many rules and norms. Often, the intentions of these rules and norms and the way they function are not at all obvious from casual observation. We will see that there are always many such norms and rules involved in the use of the commons—some obvious, some very subtle.

In summary, at the time Hardin wrote his now-classic article, the work on collective action was rooted in rational choice theory. A key assumption of this theory was that actors made rational (calculated) decisions based on selfish motives (weighing individual costs and benefits). The implications for policy were clear: to avoid overharvesting of shared resources it was critical to establish private property rights or tax the use of the commons. Much work since has shown that this simply isn’t the case.

1.5 The tragedy is not inevitable

Since Hardin’s essay, an increasing awareness has emerged that tragedy is not the only possible outcome when people share a common resource. There are many examples of long-lasting communities that have maintained their shared resources effectively. Since the 1980s there has been a steady increase in interdisciplinary efforts to debunk the simplistic view of the tragedy of the commons. Elinor Ostrom (Figure 1.4) and others showed through comparative analysis of many case studies that communities can self-govern their shared resources.

Elinor Ostrom was a political scientist who developed a theoretical framework to study the ability of communities to overcome the tragedy of the commons. This research earned her the 2009 Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel (better known as the Nobel Prize in Economics). Her Ph.D. thesis, which she finished in 1965, focused on the management of shared groundwater resources in Southern California. In her first fifteen years on the political science faculty at Indiana University she studied police forces in U.S. cities, seeking to discover which types of organizations led to the most effective policing.

Because she worked on various types of projects related to the governance of shared resources, she started to see commonalities. Since the early 1980s, Ostrom developed a more theoretical understanding of the institutions, rules and norms that communities use to organize themselves. This led her to develop the Institutional Analysis and Development (IAD) framework, which is a core framework in this book.

During the mid-1980s Ostrom returned to the study of problems related to the governance of environmental commons. An increasing number of scholars at the time were realizing that reality clashed with the conventional view that the use of a shared resource would end in environmental disaster. Ostrom proved instrumental to this revolution in thinking by leading an effort to compile hundreds of case studies—successes and failures—from the lobster fisheries of Maine to the irrigation systems of Nepal.

The comparative analysis of these case studies allowed her to identify features that were more common in successful cases. In her 1990 book Governing the Commons, she identified eight design principles that characterized successful self-governance strategies, including having monitors who are accountable to the users of a resource and cheap mechanisms for conflict resolution. Those principles are discussed in Chapter X and have held up to the test of time.

Since the early 1980s, an increasing number of anthropologists, sociologists, political scientists, ecologists, and many other scholars have been documenting examples of resources shared in common that have been managed sustainably for a long time without private property rights or governmental interventions. This led to the development of a community of scholars who came together to create the International Association for the Study of the Commons of which Elinor Ostrom was the first president.

The work coming out of this community has provided an alternative framework for studying the use of shared resources, i.e., resources held in common. The material discussed in the coming chapters is largely based on this alternative framework which has been widely recognized. Besides a Nobel Prize in Economics (which was seen by Ostrom as a recognition of the whole research community in this area, not an individual accomplishment), insights derived from this research are increasingly applied to governance and policy issues. We worked with Ostrom from 2000 till her death in 2012, and started developing a broader perspective of her framework, which is the focus of this book.

Applications of Ostrom’s work can be found in organizations that manage development projects in developing countries, advance agricultural practices to improve food security, and protect biodiversity. Moreover, the insights on how to sustain the commons are increasingly applied to non-traditional commons such as in the areas of knowledge, culture, education, and health. For example, the communication revolution driven by the internet has generated all kinds of new challenges related to governing the digital commons. Creations consisting mainly of information (movies, books, music) are so easy to copy, that many get distributed without any payment to the owners of the intellectual property rights. Strangers can post improper comments to websites. Emails are sent around in order to gain access to your private information.

1.6 Outline of the book

The book consists of 7 parts. The first part of the book introduces concepts like the commons, collective action, shared resource and shared infrastructure, and the related governance challenges at different levels of scale. The second part, introduces basic concepts and frameworks such as institutions, the institutional analysis and development framework, and action arenas. These concepts will provide the key theoretical foundation for analyzing problems related to the shared resources. We define institutions, the rules and norms that structure human interactions. This is a very broad concept but we will see that understanding the rules and the norms related to the use of the shared resources helps us understand how to sustain them. We will use the general terminology of “institutions” rather than of private property or markets, since those two examples are vague and imprecise definitions of clusters of possible institutional arrangements. The institutional analysis and development (IAD) framework that we will discuss in this book provides a more general and accurate way of studying institutions and their performance. When we focus on action arenas, a key component of the IAD framework it enables us to dissect what are the incentives, the possible actions, and the positions of people who are using the shared resources.

Part 3 will introduce concepts from system science and apply them to collective action and problems of shared resources. We will discuss feedback loops (positive and negative), resilience and tipping points.

Part 4 introduces an extension of the IAD framework by introducing resilience and robustness concepts with infrastructure in coupled infrastructure systems. Discuss different type of infrastructures. Discuss infrastructure related to water management to illustrate the framework in more detail.

Part 5 will focus on current challenges of different types of infrastructure, from maintaining roads and bridges, to the provision of schooling and health care

Part 6 explores the need for a societal transition to a new configuration of our society to reduce the pressure on the environment, and to cope with the consequences of the irreversible changes we already have made. What transitions are possible, and what is needed to make those changes.

Part 7 list some of the practical lessons from this book. We do not have a solution to the problems humanity is facing, but building on the transdisciplinary knowledge discussed in this book we provide some guidelines on how to bring those insights into practice.

1.7 Critical reflections

Commons are natural and cultural resources that are shared by many people. People can affect the commons by harvesting from them and making contributions to their construction and/or preservation. The core question this book attempts to address is how we can sustain the commons. Garret Hardin introduced the notion of the tragedy of the commons which can occur if people share a resource. The opportunistic behavior of individuals can lead to overharvesting of the shared resource. The only way to avoid the tragedy, according to Hardin, is to establish private property rights or tax the use of the commons. Elinor Ostrom and her colleagues show from case study analysis that overharvesting is not inevitable and that successful self-governance of the commons is possible.

1.8 Make yourself think

1. Come up with commons you experience yourself.

2. Are these commons functioning well?

3. Did your grandparents use different commons than you do?

4. Now that you know about the commons, can you relate the idea of the commons to the budget discussions in Washington D.C.?

1.9 References

Hardin, G. (1968) Tragedy of the commons. Science, 162, 1243–1248.

Myers, R. A. & Worm, B. (2003) Rapid worldwide depletion of predatory fish communities.Nature, 423, 280–283.

Ostrom, E. (1990) Governing the commons: the evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press.

Ostrom, E. (2005) Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.