5 Action Arenas and Action Situations

Key Concepts

In this chapter we will:

- Learn how action situations define the structure of interactions

- See that adding individuals to an action situation leads to an action arena

- Dissect the structure of an action situation

5.1 Action arenas

Whenever two or more individuals are faced with a set of potential actions that jointly produce outcomes, these individuals can be said to be “in” an action situation. Within an action situation, a participant occupies a certain position. The same participants can interact in another action situation where they occupy different positions.

An action arena combines the action situation, which focuses on the rules,norms and biophysical context, with the participants who bring with them their individual preferences, skills, and mental models, i.e. the attributes of the community. The need to distinguish between action arenas and action situations is a result of the fact that when different participants occupy positions in the same action situation, this may lead to very different outcomes. Put simply, the action situation remains the same for a given period, but a new action arena is generated every time a new set of participants enters the action situation. For example, an action situation might be the marketplace on eBay. The same product offered by different sellers might not lead to the same price since it depends on the preferences and actions of the different participants who enter the action situation and generate a new action arena. Other examples of action situations include resource users who can extract resource units (such as fish, water, or timber) from a shared resource, politicians in congress crafting new laws, and schools with educators and students.

Likewise, the same participants can have very different types of interactions in different action situations. This could be the result of the simple fact that the participants in different action situations occupy different positions. This could also be due to different rules on the information available in different action situations. A boss and their employee in one action situation might become two squash players in another arena. The boss and employee interact very differently in terms of their power relationship—they leave their professional relationship at the squash court door.

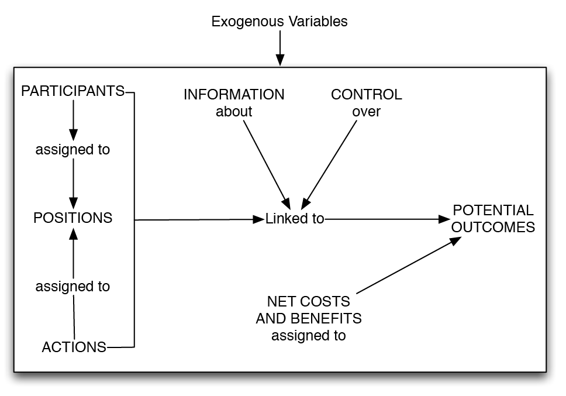

The structure of all action situations can be described and analyzed by using a common set of variables. These are: (1) the set of participants, (2) the positions to be filled by participants, (3) the potential outcomes, (4) the set of allowable actions and the function that maps actions into realized outcomes, (5) the control that an individual has in regard to this function, (6) the information available to participants about actions, outcomes, and the linkages between them, and (7) the costs and benefits—which serve as incentives and deterrents—assigned to actions and outcomes. The internal structure of an action situation can be represented as shown in Figure 5.1. In addition to the internal structure, whether a situation will occur once, a known and finite number of times, or indefinitely, affects the strategies individuals adopt. And again, with the same action situation but different individuals participating, we have a different action arena.

Within a college course, participants have different positions for which different actions are assigned. Students have different responsibilities compared to the professor and teaching assistant. For example, a professor has information regarding the scores of all the students and the authority to give the grades. Students do not have full information about the scores of individual students in the classroom. They may, however, have aggregate information about all the student scores (i.e., the average). A teaching assistant can grade essays based upon an agreed-upon evaluation criteria, but it is the responsibility of the professor to give the grades. Some of the costs and benefits for a professor include the amount of time spent in preparing the class content and lectures and grading and the wage she receives for doing so. The consequences of different allocations of time invested can be seen in the grades the students receive and the evaluations the professor receives. Also, the student has to balance the investments of time in taking the course and other activities and this choice will be materialized in the grade received.

An individual can take a class one year (be in the position of the student), and become a teaching assistant the next year. That is, the same participant can occupy many different positions. The student could attend a course in the morning as a student, then act as a teaching assistant for a different course in the afternoon. In the morning course, the student has no information about other students’ grades. In the afternoon course, she will have more information about the individual students, but now also bears more responsibility for the performance of the students in the class.

The number of participants and positions in an action situation may vary, but there must be at least two participants in an action situation. Participants need to be able to make choices about the actions they take. The collection of available actions represents the spectrum of possibilities by which participants can produce particular outcomes in that situation. Information about the situation may vary, but all participants must have access to some common information about the situation otherwise we cannot say that the participants are in the same situation. The costs and benefits assigned to actions and outcomes create incentives for the different possible actions. How these affect the choice of participants depends on the preferences, resources and skills participants have. Who has power? Not all participants may have the same level of control, allowing some to have substantial power over others and the relative benefits they can achieve.

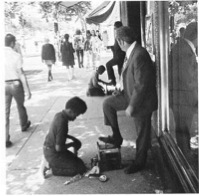

There is inequality in wealth between countries and within countries. There are differences in information access and access to decision-makers between the haves and the have-nots. Poor people typically have fewer possible actions available to them than do rich people. With wealth comes access. The rich man in Figure 5.2 can polish his own shoes but can also pay somebody else to do this. The poor man does not even have shoes that need to be polished let alone resources to pay somebody else to polish the shoes. This example shows that not every person can occupy each possible position in an action situation. Both men can occupy the positions of citizen, or legal adult, but only the wealthy man can be both polisher and “polishee.” The fact that the poor man cannot be the “polishee” is due to one of two factors (1) formal rules or norms about social roles and occupations allowed for different social roles such as the caste system in India or (2) because the poor man lacks the resources or capacity to be the “polishee.” In the first case, it is the action situation that limits the actions of the poor man. In the second case, it is an outcome of the action arena that limits his choices. Whether an individual can occupy a certain position may be affected by wealth, education, elections, inheritance, passing a test, age, gender, and many other criteria. As we will see in later chapters, the rules that affect positions play an important role in how communities can sustain their commons.

When we study an action situation, we analyze the situation as given. We assume the structure of the action situation is fixed for at least the short run. Then we can analyze the action arena by exploring assumptions of the likely human behavior of the individuals leading to particular outcomes.

Within a particular situation, individuals can make choices about their own actions. However, in the longer term, individuals may—at least those who are living in an open society—take actions that may eventually affect the structure of action situations (i.e., the choices others can make). This is possible when one is able to change the rules affecting the action situation. For example, the rules regarding the marketplace at eBay have changed over time because participants have learned what works and what does not work. If action situations do not lead to good outcomes, one may attempt to change the rules. To do so, they must move to action situations at a higher level of decision making such as collective-choice or constitutional-choice action situations, where the outcomes generated are changes in the rules that structure other action situations such as who can participate, what actions are available to them, what payoffs are associated with actions, etc. In a closed society, individuals at an operational level may have little opportunity to change rules at any level and may find themselves in highly exploitative situations. Democratic countries are examples of open societies, while dictatorships are examples of closed societies (see Figure 5.3). We discuss the process of shifting to higher-level action situations in the last half of this chapter.

5.2 The basic working parts of action situations

Let us now discuss the elements of an action situation so we can begin to understand what is common to all of the interactive situations we may observe or experience in our lives.

5.2.1 Participants

Participants in an action situation are assigned to a position and capable of making a choice between different possible actions. The participants in action situations can be individuals but also corporate actors such as nations, states in a federal system, private corporations, NGOs, and so forth. Whenever participants are organizations, one treats them in the situation as if they were a single individual but one that is linked to a series of additional situations within their own organization. When one is interested in the outcome of an action situation for the organization, we may ignore the linked situation and just focus on the strategy of the organization as an individual actor. However, if we notice that there are problems with the functioning of an organization within an action situation, we may look at the functioning of the organization itself, and study the action arena of that organization. As such, action arenas can be composed of action arenas of lower level actors. For example, the United Nations consists of many countries. To understand the functioning of the action arena of the United Nations, we may look at the ambassadors as participants, or we may look into the action arena of a country in which the ambassador also participates to understand the decisions made by that ambassador.

Several attributes of participants are relevant when representing and analyzing specific situations. These include (1) the number of participants, (2) their status as individuals or as a team or composite actor, (3) and various individual attributes, such as age, education, gender, beliefs, knowledge, skills, and experience.

The number of participants

The focus of this book is on those action situations associated with governing shared infrastructure. Therefore, action situations that are of interest to us require at least two participants where the actions of each affect the outcomes for both. This could be two farmers sharing a water source.

The specific number of participants is often specified in detail by formal regulations, such as for legislation (number of seats in the Senate and Congress), juries (number of jury members), and most sports (number of members on a team). Some descriptions of a situation, however, specify the number of participants in a looser fashion such as a small or a large group, or face-to-face relationships versus impersonal relationships. Since many other components of an action situation are affected by the number of participants, this is a particularly important attribute in the analysis of any action situation. Figure 5.4 shows some examples from sports illustrating the number of participants in action situations.

The individual or team status of participants

Participants in many action situations may be individual persons or they may represent a team or composite actors, such as households. A group of individuals may be considered as one participant (a team or organization) in a particular action situation. What might be the conditions in which it makes sense to treat a group of individuals as a participant?

To consider a group of individuals to be a participant, one must assume that the individuals intend to participate in collective action. One needs to assume that the individuals who are being treated as a single actor intend to achieve a common purpose. Sometimes there are groups of individuals who share many similar characteristics, such as “veterans,” “urban voters,” or “legal immigrants,” but they have different individual preferences and do not act as a cohesive team. Corporate actors, such as firms, are not so dependent on the preferences of their members and beneficiaries, because they are legally defined as an individual entity. The activities in firms and organizations are carried out by staff members whose own private preferences are supposed to be neutralized by formal employment contracts.

A fully organized market with well-defined property rights, for example, may include buyers and sellers who are organized as firms as well as individual participants. Firms are composed of many individuals. Each firm in a market is often treated as if it were a single participant.

So when do we consider a group of individuals as a collective rather than as a bunch of individuals? This depends on the questions we have. The action arena of a basketball game, for example, maybe represented as having either ten participants or two teams composed of five individuals. If we are interested in studying a league or a tournament, we will include more teams and focus on the teams as participants rather than as individual players. If we are interested in the performance of a single team within the league we would look at individual players, coaches, trainers, and owners.

Attributes of participants

Participants differ in their characteristics such as their skills, ethnic background, education, gender, values, etc. These characteristics may influence their actions in some situations, but not in others. The educational level of participants is not likely to affect the actions of drivers passing one another on a busy highway. But when the participants meet each other in an emergency room in the positions of patient and physician, education becomes an important attribute. Whether gender or ethnic background is important varies between cultures and countries. In some cultures, female patients are not allowed to be examined and treated by male physicians. During the Apartheid regime in South Africa, Black patients did not receive the same treatment as White patients did.

The outcomes of many situations depend on the knowledge and skills of the parties. Experienced drivers will have on average a different driving style compared to younger drivers. This fact is born out in the differences between insurance policies for the two participants. Drivers who have a reputation with an insurance company for getting involved in accidents will have to pay a higher insurance premium compared to those who are accident-free.

5.2.2 Positions

Participants occupy positions in action situations. Examples of positions include students, professors, players, referees, voters, candidates, suspects, judges, buyers, sellers, legislators, guards, licensed drivers, physicians, and so forth. It is very important to understand that “positions” do not refer to people, but rather to roles that participants can play in an action situation. For example, in a market situation (in your local mall), the same person may be a “seller” when they are at work at the Apple Store helping customers choose their latest iPhone, and a “buyer” when they go for lunch in the food court. Thus, positions and participants are separate elements in a situation even though they may not be clearly so identified in practice.

In practice, the number of positions is frequently significantly less than the number of participants. In a class, there are typically only two positions—student and professor—while there may be hundreds of participants. Hunters who have a valid license all occupy the position of a licensed hunter; and while there are more than a billion participants at Facebook, there are only a limited number of positions (such as the person featured on the webpage, or the administrator of a page representing an organization).

Depending on the structure of the situation, a participant may simultaneously occupy more than one position. All participants will occupy whatever is the most inclusive position in a situation — member, citizen, employee, and the like. In a private firm, additional positions such as foreman, division manager, or president will be occupied by some participants while they continue to occupy the most inclusive position—that of employee. Some examples of positions are given in Figure 5.5, where some positions are filled by election, others are filled by selection after an interview.

Positions connect participants with potential actions that they may take in an action situation. Not all positions have the same potential actions. A surgeon can do surgery on a patient. It is likely not advisable to allow the patient this potential action, unless in the unlikely event that the patient happens to be a surgeon too. Other positions are less restrictive. Every person with a driver’s license shares a large set of potential actions with every other driver. Some drivers have special positions and additional potential actions, such as drivers of ambulances or large trucks.

The President of the United States can sign a bill into new legislation, which confirms that the new legislation will be implemented. The President can only sign such a document under particular conditions (agreement in the Senate and Congress), but a signature of a regular citizen does not have the same effect. A U.S. citizen who has registered as a voter can vote, but a permanent resident (Green Card holder) cannot register as a voter, even if such a permanent resident is a professor at a prominent university.

The nature of a position assigned to participants in an action situation both defines the set of authorized actions and sets limits on those. For example, licensed drivers may operate a motor vehicle on a road or highway, but this action is also restricted by speed limits. Those who hold the position of a member of a legislative committee are authorized to debate issues and vote on them. The member who holds the position of chair can usually develop the agenda for the order of how issues will be brought before the committee or even whether a proposal will even be discussed. The order of events on this agenda may affect how the votes turn out.

If you do a group project how do you organize a group? Will different group members have different roles? Is one of the members leading the discussion?

Participants may occupy different positions, but which position one can hold is not always something a participant can choose. A defendant in a criminal trial does not control her movement into or out of this position. A candidate for the U.S. Congress can certainly influence her chances of winning an election and securing the position, but does not have full control. In the end, this decision is in the hands of voters. Holding the position of a pedestrian in traffic is available without much limitation to most people. Individuals have to compete vigorously for getting a tenured professorship at a university, but once obtained, they may hold their positions for life, subject only to legal actions. This might be true for universities in the U.S., but in most European countries professors are required to retire at the age of 65 and are removed from their position as a tenured professor.

5.2.3 Potential outcomes

In the case of health care reform, there are different potential outcomes that can be discussed: total costs of healthcare, access to health care, distribution of costs and benefits, quality of healthcare, etc. Which outcome will weigh most in the design of policies is a political decision.

When we want to understand how rules, attributes of the environment, or attributes of the community change an action situation, careful attention must be given to how participants value certain outcomes. If there is a market where goods are exchanged at known prices, one could assign a monetary value to the goods. If there are taxes imposed on the exchange of goods (a sales tax), one could represent the outcomes in a monetary unit representing the market prices minus the tax. If one wanted to examine the profitability of growing rice as contrasted to tomatoes or other cash crops, one would represent the outcomes in terms of the monetary value of the realized sales value minus the monetary value of the inputs (land, labor, energy, fertilizer, and other variable inputs).

To examine the effect of rules, one needs to distinguish the effect of material rewards from financial values. For example, the physical amount of goods produced during a particular time period is different from the financial rewards to workers and owners for that time period. If no goods are sold, the financial rewards for the owner might be negative, but the worker may still receive a reward in exchange for the hours worked to produce the goods. Besides monetary values and physical quantities of goods, participants also have internal values, such as moral judgment, that they use to examine potential outcomes. Gun ownership can be evaluated based on the numbers of different types of guns owned, the monetary value of the gun collection, and the moral value placed on gun ownership.

Frequently the outcomes are assumed to be the consequence of self-conscious decisions, but there can also be “unintended outcomes.” For example, oil spills in the Gulf of Mexico are not an intended outcome of operations of oil companies (Figure 5.6).

5.2.4 Actions

Participants assigned to a position in an action situation must choose from a set of actions at any particular stage in a decision process. An action can be thought of as a selection of a setting or a value on a control variable (e.g., a dial or switch) that a participant hopes will affect the outcomes. The specific action selected is called a choice. A complete specification of the actions, taking in all possible variations of the action situation is called a strategy. It is important to note that it might not always be clear to participants what all the valid actions are in an action situation. A switch may clearly indicate two different positions, but sometimes participants are much more innovative in the use of possible actions in an action situation. Calling somebody with a mobile phone can be very expensive in some places. As a result, people may use the technology in a different way than was intended by the manufacturers. For example, in some communities, signaling systems evolved where the receiver of a mobile phone call can understand the message from simply counting the number of rings of the call and the information about who the caller is from the display. Users in such situations may seldom use their mobile phone for an actual voice call.

What is the change of outcome for the mobile phone service provider when people use this strategy?

5.2.5 Control

The extent to which participants have control over aspects of the action situation vary widely. Obviously, the position that a participant occupies affects the power of this participant (her ability to affect the actions of other participants and outcomes). The level of control a participant has can, therefore, change over time, for example, if she changes her position. Barack Obama acquired a new repertoire of actions and control when he assumed office on January 20, 2009. And this repertoire has changed over the years from being a lecturer and giving grades at the University of Chicago, a community organizer, a member of the Illinois Senate, and a member of the U.S. Senate. Each position held certain duties and rights. Leaving a position also means losing the duties and rights that hold to the specific position, as happened too with President Obama on January 20, 2017. The issue of control, or ‘controllability’ is a very general feature of coupled infrastructure systems as we will discuss in further detail in Chapter 8.

5.2.6 Information about the action situation

What is the information participants have in an action situation? In an extreme case they have complete information and know the number of participants, the positions, the outcomes, the actions available, how the actions are linked to outcomes, the information available to other players, and the payoffs available. If they know what other participants will do, participants are said to have perfect information. Of course, perfect information is an extreme case especially when people make their decisions privately. Often there is no perfect understanding of how actions will lead to outcomes, or what others plan to do. Even if people communicate and negotiate what everyone will do, the actual actions may turn out different since people make mistakes or cheat.

In many situations, there is asymmetric access to the available information. For example, in work situations, a boss cannot know exactly what employees are doing. That is why providing an incentive to increase productivity is a challenge. The same holds for insurance companies. Your insurance company does not have perfect information about your driving abilities and health conditions, but makes an informed guess based on statistics of historical events. Would you like your insurance company to have access to your genetic profile? What about your driving behavior? The car insurance company Progressive allows customers to join a voluntary program where a device is installed in your car to track your driving style. One can save a significant amount on their car insurance with proper driving style.

As with ‘controllability’ mentioned above, the capacity to gather information and access to that information is also a very general feature of coupled infrastructure systems. The general notion for the availability of good information is referred to as ‘observability’ in general systems theory as we will discuss in Chapter 8.

5.2.7 Costs and benefits

To evaluate the outcomes of the actions taken in the action situation we have to look at the costs and benefits. These costs and benefits accumulate over time. Not all participants will experience the same costs and benefits. Sometimes the positions that participants hold affect their cost and benefits since it affects the compensation, penalties, fees, rewards, and opportunities. A physician receives a monetary benefit from doing a treatment while the patient will pay to receive an improvement in their health condition. Even if participants hold the same position, like players on a sports team, their rewards vary as defined by their individual contracts.

If we study action arenas we need to make a distinction between the physical outcome and the valuation that a participant assigns to that outcome. In economics, the value assigned by participants is often referred to as utility. Individual utility is a summary measure of all the net values to an individual of all the benefits and costs of the outcome of a particular action situation. Utility might increase with an increase in profit, but depending on the study at hand, it may also include elements like joy, shame, regret and guilt.

For example, driving above the speed limit can save you time. However, if you are caught you will have to pay a traffic fine (Figure 5.8). You may challenge a ticket by appearing in court, yet this will take time and may have other costs associated with it. Paying the fine (accepting guilt for the traffic violation) could also result in higher car insurance and accumulate points on your driving record. If you accumulate too many points on your driving record, your license may be suspended. Not paying a ticket in time will lead to additional penalties.

5.2.8 Linking action situations

In reality, people make decisions in different action situations that are often linked together. Rarely do action situations exist entirely independently of other situations. For example, new laws in the U.S. need to be approved by the Congress and the Senate before the President may sign it. Signing a bill is meaningless unless the bill has successfully passed through the Congress and Senate action arenas.

Given the importance of repeated interactions to the development of a reputation for reciprocity and the importance of reciprocity for achieving higher levels of cooperation and better outcomes over time, individuals have a strong motivation to link situations.

Action situations can be linked through organizational connections. Within larger organizations, what happens in the purchasing department affects what happens in the production and sales department and vice versa. Sometimes action situations are structured over time. For example, a tournament or sport competition is a description of how players (e.g., tennis) or teams (e.g., basketball) will proceed through a sequence of action situations. In other examples, action situations are not formally linked. Farmers who have successful innovative practices in deriving better profits are frequently copied by others.

Another way in which action situations can be linked is through different levels of activities. We can distinguish three levels of rules that cumulatively affect the actions taken and outcomes obtained:

- Operational rules (or rules-in-use in the IAD Framework) directly affect day-to-day decisions made by the participants in any setting. These can change relatively rapidly—from day to day.

- Collective-choice rules affect operational activities and results through their effects in determining who is eligible to be a participant and the specific rules to be used in changing operational rules. These change at a much slower pace.

- Constitutional-choice rules first affect collective-choice activities by determining who is eligible to be a participant and the rules to be used in crafting the set of collective-choice rules that, in turn, affect the set of operational rules. Constitutional-choice rules change at the slowest pace.

An example of an operational-level situation is a group of fishers who decide where and when to fish. At the collective-choice level the group of fishers may decide on which seasons or locations to implement bans on fishing. At the constitutional-choice level decisions are made regarding the conditions required in order to be eligible for membership in the group of fishers.

Figure 5.9 illustrates the different levels of rules related to a class at a university. Within a classroom, decisions are made based on the rules set in the syllabus. Day-to-day decisions include what the assignments are for next week, who will give a talk, and when students can come to office hours. In order for a regular course to be approved, a committee (upper right) will review the proposed syllabus and make a recommendation to approve or not approve the course. The committee also solicits comments of departments that provide similar courses to avoid potential conflicts. The university senate will come into play when new degrees are proposed (middle left). Finally, the upper administration of the university will be involved in decisions that have university-wide impact, such as changing tuition rates. Such a tuition raise will have to be approved, at least for public universities, by a state level committee.

5.2.9 Outcomes

It is difficult to predict the outcomes of rule changes made in action situations. Changing the rules in one action situation may have consequences in other action situations. The difficulty of predicting the consequences of changes shows that we have to closely observe what is happening before rules are changed and after rules are changed. This suggests that we should view policies experiments, and closely observe these experiments in order to learn and have a better understanding of what will happen in a similar case in the future.

Besides the difficulty of predicting outcomes, how to evaluate outcomes is also often not immediately evident. There are different criteria that one can use to evaluate the outcomes:

- Economic efficiency—what are the costs relative to the benefits?

- Equity—how are costs and benefits distributed among the participants?

- Accountability—are participants in leadership positions accountable for the consequences of their decisions?

- Conformance to general morality, i.e. procedural justice—are the procedures fair, is cheating detected, and are promises kept?

- Sustainability—how do the outcomes evolve over time? And what are the consequences of decisions on the underlying system?

In order to evaluate the outcomes one needs to evaluate trade-offs associated with the different criteria. If some groups are affected differently than others, it will be important to define procedures in the collective-choice or constitutional-choice rules to address such differences. For example, the outcome of changing the criteria for student-loans will not have the same consequence for each individual student. It would be important to consider the different types of outcomes for different types of participants and develop agreements regarding how to evaluate such outcomes.

5.3 Critical reflections

The concept of action arenas was the main topic of this chapter. An action arena consists of an action situation that defines the structure of interactions, actions and outcomes, and the individuals, organizations or nations who may participate in the action situation. When two or more participants interact, there is an action arena where participants hold positions, and can make decisions. Not everybody in an action situation can take the same actions, or has the same level of information. The consequences of the actions are the outcomes of the action situation, which can be evaluated differently by each participant in the action situation.

5.4 Make yourself think

- 1. What positions do you hold in different action situations? Provide some examples.

2. What is an action situation you experience regularly? What are the possible outcomes in this situation? What actions can you take? Be sure to distinguish between actions you may take and choices you do make.

3. Do you have an example from your own personal experience where you have experienced the same action situation but with different participants that led to a different action arena and a different outcome?

5.5 References

Ostrom, E. (2005) Understanding institutional diversity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.