8

Teacher Introduction:

“A picture is worth a thousand words,” goes the famous saying. Political cartoonists certainly hope so. For centuries, American cartoonists have drawn political leaders to capture some essential idea or message in a few symbols. Starting around 1900 Colorado was lucky to have a pioneering cartoonist develop a rich tradition of work. Denver Post illustrator Wilbur Steele began to draw a daily cartoon featuring city, state, and national leaders who had misused their influence and authority. He, like so many other cartoonists, hoped that his pictures could help fight evil and corruption. Steele also used his single-framed images to celebrate successes and express hopes for positive change. This chapter allows students a chance to develop their visual literacy skills by interpreting a range of cartoons from American and Colorado history.

Artist Wilbur Steele spent many years drawing one of Denver’s most famous mayors, Robert Speer. Known today for promoting the Civic Center, applying the City Beautiful ideal, and overseeing construction of the boulevard that bears his name, Robert Speer left an enduring legacy in Denver. Less well known is the intense criticism he drew for his sneaky and illegal electioneering strategies. His political party, the Democrats, had organized a network of loyal supporters, especially in what is today Lower Downtown or LoDo. These supporters were experienced in manipulating elections by “repeating” or voting as often as they could. They registered dead people; disguised themselves and assumed other people’s names; and bribed and intimidated other voters to choose the Democrats. The chief of police at the time, Michael Delaney, promised these Democratic loyalists protection from prosecution. The Republicans had a similar network, or machine, that operated in other parts of the city and state.[1]

But Robert Speer was the leader of the Democratic Party machine. Denver Post cartoonist Wilbur Steele began drawing cartoons of candidate Speer called attention to his key role in this network. In fact, Steele seemed to want to warn the voters of Denver that Speer was dangerous, encouraging violence against voters who disagreed with him. Steele was especially focused on that Democratic party machine with “Boss” Speer at the head of it.

Steele captured the positive and negative aspects of Speer’s public record with his front-page cartoons. Steele was at times a fierce critic and at others a loyal supporter. By reviewing a range of Steele’s cartoons, students can get a sense of Speer’s legacy one of Denver’s greatest mayors.

Though consistently innovative in his 28-year run at the Post, Steele also tapped a growing tradition of cartooning in America when he started in 1897. Some of the earliest and most successful American political cartoons that inspired Steele were drawn by German-speaking immigrants in the late nineteenth century. Thomas Nast and Joseph Keppler were born in Europe but drew popular cartoons for early magazines in New York. After the Civil War, they often drew political leaders, highlighting political corruption and abuses of power. Before interpreting Steele’s work, students will benefit from examining some of the symbols and images developed by Nast and Keppler.

These men contributed to the boom in newspaper and magazine circulation that shaped public life in America around 1900. Most major cities had dozens of daily or weekly newspapers. Denver had more than ten. In an era before the internet and television and even before radio, print media were central for sharing and debating information. Though relying heavily on text, these early newspapers also embraced cartoon images along with photography. Reproducing them was not cheap or easy, but cartoons offered a quick way to hook a reader. The Denver Post, for example, featured Wilbur Steel cartoons on the front page, above the fold in the paper. They were typically the first thing readers saw in the paper.

As a visual source, cartoons offer many opportunities for students. They are immediately accessible and simple in ways that written text often is not, especially for new and young readers. The basic question “What do you see in this cartoon?” can start a classroom discussion, even for students with little background knowledge.

And then the fun begins. After an initial conversation about basic elements within a frame, students can develop new skills in thinking symbolically. What might this donkey or that elephant represent? Did this artist capture only his own, idiosyncratic worldview, or did she or he somehow describe a feeling that many people had and could embrace? Asking these more abstract questions of political cartoons can be challenging, particularly because students do lack much background knowledge of the time or era. But with support from teachers, they can begin to build that background and learn to view images more critically.

Thomas Nast and Wilbur Steele offer students a chance to think symbolically in many ways. The political controversies of New York in the 1870s or Denver in the 1900s can appear at first remote and confusing. Yet these cartoonists distill key problems in issues in visual representations that are powerfully meaningful. The feeling the cartoons evoke about politics and government can be more immediately discerned from the cartoons that from a lengthy description of procedures or events. Even young students can begin to build a framework for understanding what happens when leaders are corrupt or fair.

Last, political cartoons do possess more power than many students will at first realize. The sad fate of Charlie Hebdo cartoonists in 2015 suggests that cartoons can move people to violent retaliation. Some cartoons matter dearly. Yet in America, there has historically existed a public space for sharing even controversial images and symbols critical of government leaders without harassment or imprisonment. Studying cartoons like these gives one an appreciation for the First Amendment right to freedom of symbolic speech in Colorado and our nation as a whole.

***

Sources for Students:

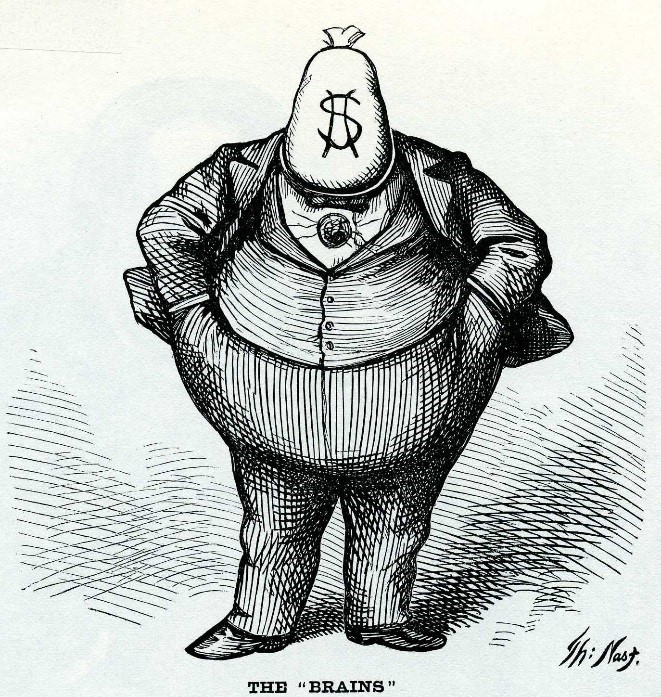

Documents 1, 2, and 3: Thomas Nast and his Cartoons

Thomas Nast was a German immigrant who drew pictures for American magazines in the 1800s. His images helped create certain traditions or patterns that other cartoonists would follow. As you look at these first few cartoons, think about the symbols and patterns that appear. Some possibilities to keep in mind: bags of money, ballot boxes, and tigers. For this artist, bags of money and tigers came to represent ideas as well as real items you could touch.

Start to create a list of symbols that you find in the cartoons and make a note about what they might mean.

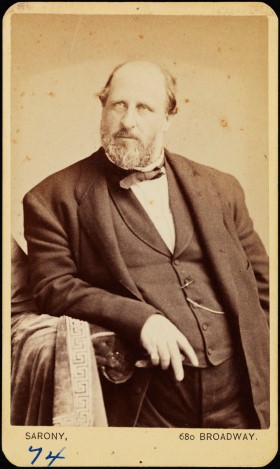

| Document 1: Thomas Nast cartoon, The ‘Brains’, (1871) | Document 2: Photograph of “Boss” William Tweed, Leader of the Democratic Party in New York City, 1870. |

|

|

[Source: Harper’s Weekly (10/21/1871) & 1870 Napoleon Sarony photograph of William Tweed. Photograph online: https://blog.mcny.org/2015/04/28/napoleon-sarony-celebrity-photographer/]

Questions:

- What do you see in the cartoon on the left?

- Thomas Nast wanted to make a comment in that cartoon about a political leader in New York City named Boss Tweed. Why is the man’s body shaped in this way? What might the “$” sign on his face mean?

- A photograph of Boss Tweed appears on the right. He was the boss of a political party, the Democrats. Do you think that Nast just couldn’t draw very well and so messed up his cartoon on the left? Why or why not?

- Tweed was very popular with many voters in New York City. Was it dangerous for Nast to draw Tweed in this way? Was he being disrespectful of Tweed?

- What might Tweed have done to deserve a picture of him as a bag of money?

***

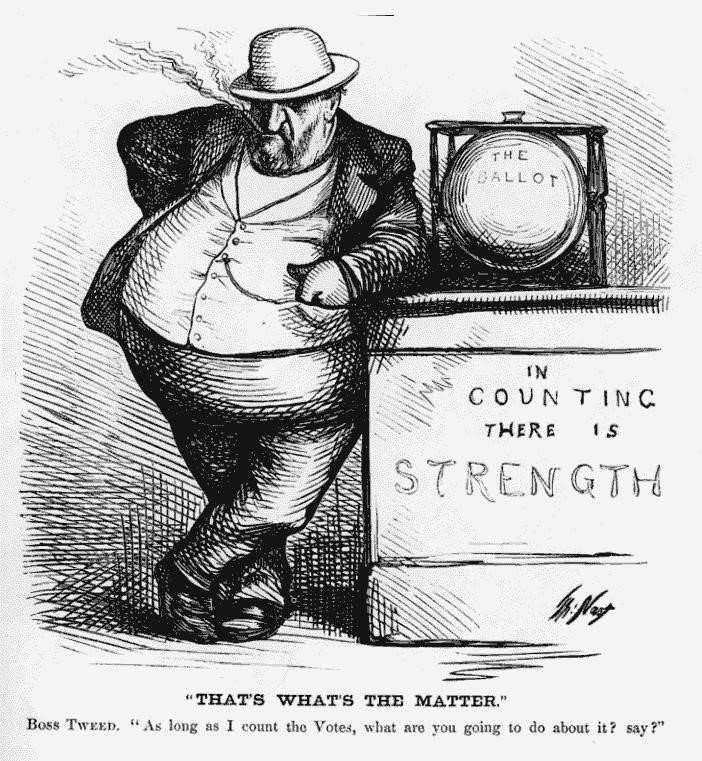

Doc. 3 Thomas Nast, “In Counting There is Strength” (1871)

In this cartoon, Thomas Nast again drew Boss Tweed of New York City:

[Source: Harper’s Weekly (October 7, 1871)]

Questions:

- Here is another Nast drawing of Boss Tweed. This time, he’s leaning next to a Ballot Box marked “The Ballot.” That was used to collect votes on election day in the 1870s. What might the words under the ballot box mean: “In counting there is strength?”

- If you were planning to vote on election day and had to walk up to Tweed standing like this next to the ballot box, would you be worried? Does he look scary or intimidating? Why or why not?

- How did Nast suggest that Tweed was corrupt or unfair when it came to votes?

- If Boss Tweed got to count all the votes himself, how often to you think his party would win? Why?

- Remember in the first Nast cartoon, Tweed looks like a bag of money. How might money be used unfairly during an election?

***

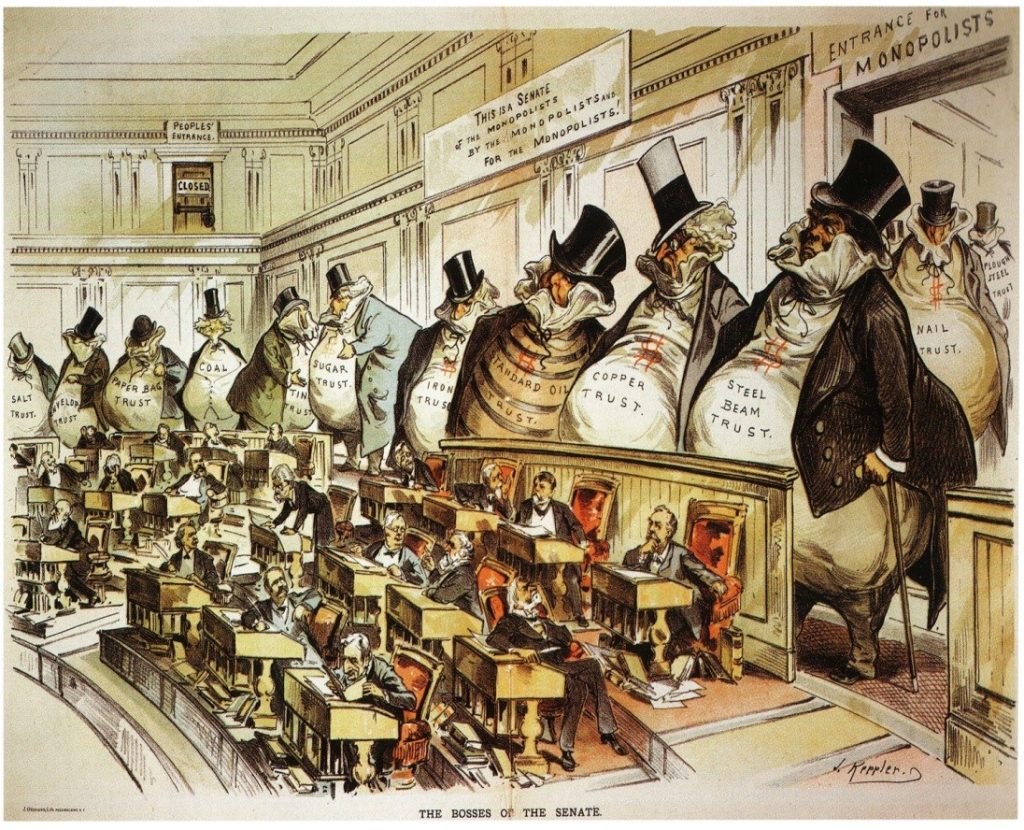

Doc. 4 Joseph Keppler, Bosses of the Senate (1889)

Another famous cartoonist was Joseph Keppler. He was born in Austria and moved to the United States in 1867. Also a European immigrant, Keppler drew cartoons around the same time that Thomas Nast did. Like with the cartoons of Thomas Nast, notice the symbols here. He seems to use the idea of a bag of money as a symbol.

[Source: Puck magazine (January 23, 1889)]

Questions:

- Here is a cartoon picture of the U.S. Senate in Washington, DC. The men in the desks are senators from different states. The men along the back wall appear much different from the senators. How?

- Again, a cartoonist drew people as bags of money. Why might he do this?

- The word “trust” can mean monopoly. You might picture what happens in the game Monopoly, when a player owns a whole row of properties and pays for hotels on all those properties. How much money does that player collect when an opponent lands on those hotels? Similarly, if someone bought sugar from the “Sugar Trust” or oil from the “Standard Oil Trust,” would they likely pay more for those products? Why or why not?

- Why did this cartoonist put monopolies or trusts in the US Senate? Did they help make laws somehow?

- Did Americans worry if very wealthy men unfairly influence their government leaders? If they bribe their leaders?

***

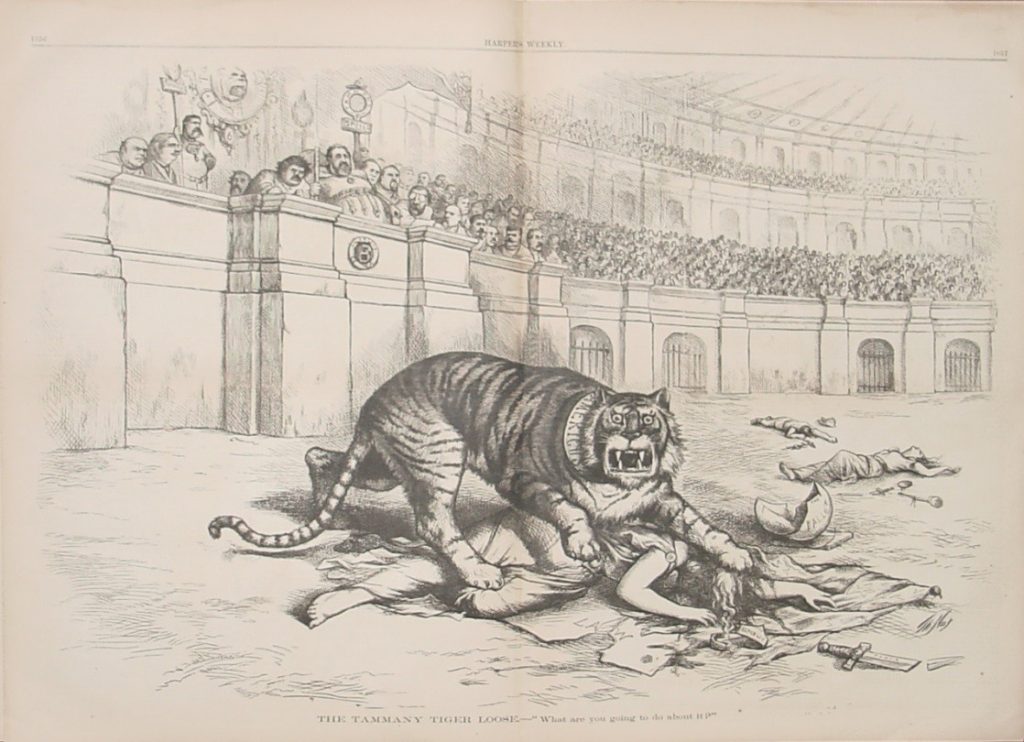

Doc. 5 Thomas Nast, “Tammany Tiger Loose” (1871)

Here Nast uses different symbols from before. Even the main person on the ground in the picture could also be a symbol.

[Source: Harper’s Weekly (Nov. 11, 1871)]

Questions:

- Here is another Nast cartoon, this time featuring a tiger on top of a woman. Should that woman be worried? Why?

- If you look carefully above and behind the tiger, you can see Nast’s picture of Boss Tweed again. Is he worried about the woman on the ground?

- The caption at the bottom of the cartoon says “The Tammany Tiger Loose.” Tammany was a nickname for Boss Tweed’s political party, the Democrats. By drawing the Democrats as a tiger, Nast wanted to give some kind of warning. What kind?

- If that woman under the tiger were a symbol, what might she represent?

- Nast suggests here that Boss Tweed and his Democratic party were somehow dangerous or even violent. How does the cartoon work to give you that feeling?

- Like the other Nast cartoons of Boss Tweed, this one is critical of Tweed. Does this make the cartoon itself dangerous? Would you expect that Tweed might want to get revenge against Nast? Why or why not?

- Should cartoonists be able to draw political leaders in ways that are not friendly or flattering to make a point about fairness? Why or why not?

***

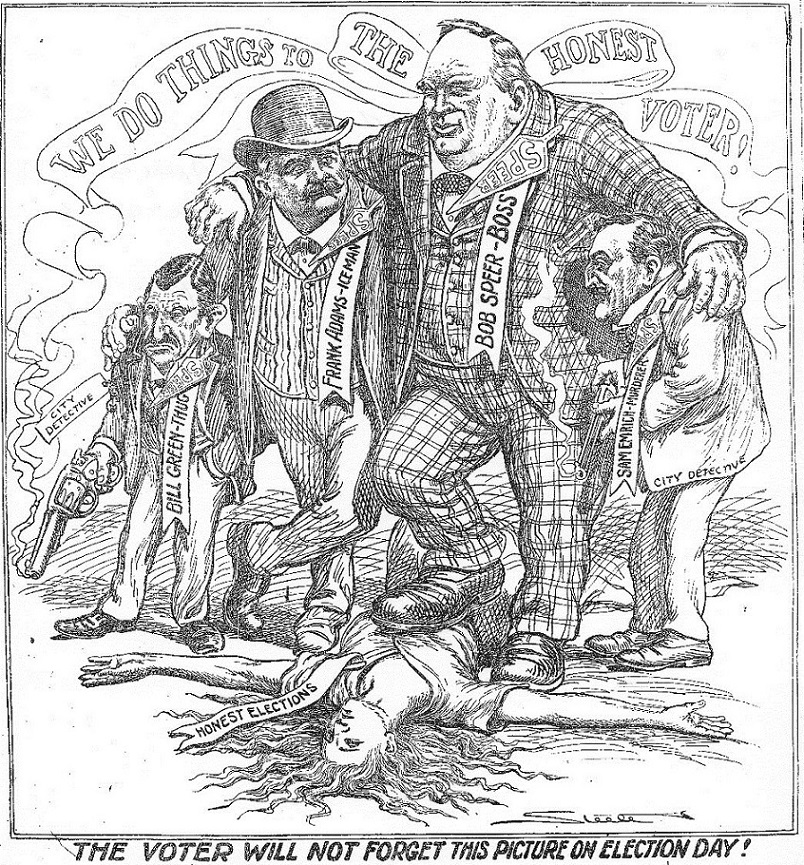

Document 6: Wilbur Steele cartoon of Speer and the “Honest” Voter (1904)

Wilbur Steele began drawing cartoons for the Denver Post in 1897. Raised partly in Denver, he had attended Colorado State University and taught school briefly before he took up cartooning. He drew cartoons several times each week for the Post until his death in 1925. Below is one of his most famous cartoons. This cartoon appeared on the front page of the Denver Post just two days for the election for Denver mayor. Bob Speer was the leading candidate for mayor at that time.

[Source: Denver Post, May 15, 1904]

Questions:

- In the cartoon above, Wilbur Steele drew candidate Bob Speer in a checkered suit standing over a woman with his foot on top of her. What does the ribbon or banner on the woman say?

- Speer’s buddies on the left and the right hold smoking guns. These were drawings of private detectives who worked with the police at times. Frank Adams, next to Speer, was a police commissioner, the boss of the police. How does the gun help suggest some kind of violence happened?

- Is the cartoon image of Speer worried about violence? Or is he somehow guilty in this cartoon?

- If you think about this cartoon symbolically, what might it mean that Speer is stepping on “honest elections”? What would a dishonest election look like?

- Speer was also a leader of the Democratic Party in Denver, and the men pictured with him here were active in the Democratic Party. Was that party somehow guilty of a crime, according to this cartoonist?

- In cartoon 5 above, Thomas Nast pictured the Democratic Party as a tiger standing on a woman. How is this Steele cartoon similar? How different?

- How might this cartoon have influenced voters before the cast their ballots?

***

Document 7: Photograph of Mayor Speer in a derby hat around 1910.

In May 1904, Robert Speer won the election to become Denver’s mayor. Steele’s cartoons apparently did not convince enough voters to vote against him. He was the leader of the Democratic Party in the city and worked on a number of projects as mayor. These included the Civic Center next to the State Capitol and the street along Cherry Creek later named for him, Speer Boulevard.

[Source: Colorado Virtual Library: http://www.coloradovirtuallibrary.org/digital-colorado/colorado-histories/20th-century/robert-speer-denvers-city-beautiful-mayor/]

Questions:

- How would you describe the expression on the face of Mayor Speer in this photograph?

- Does Speer look dangerous or threatening?

- What might he be pointing at?

- How does the car in the background help us identify when this photo was taken?

- Why might cartoonist Steele have drawn Speer in the previous cartoon to look like a thug or bully?

- How can this photo and the previous Steele cartoon together tell us something about Mayor Speer?

***

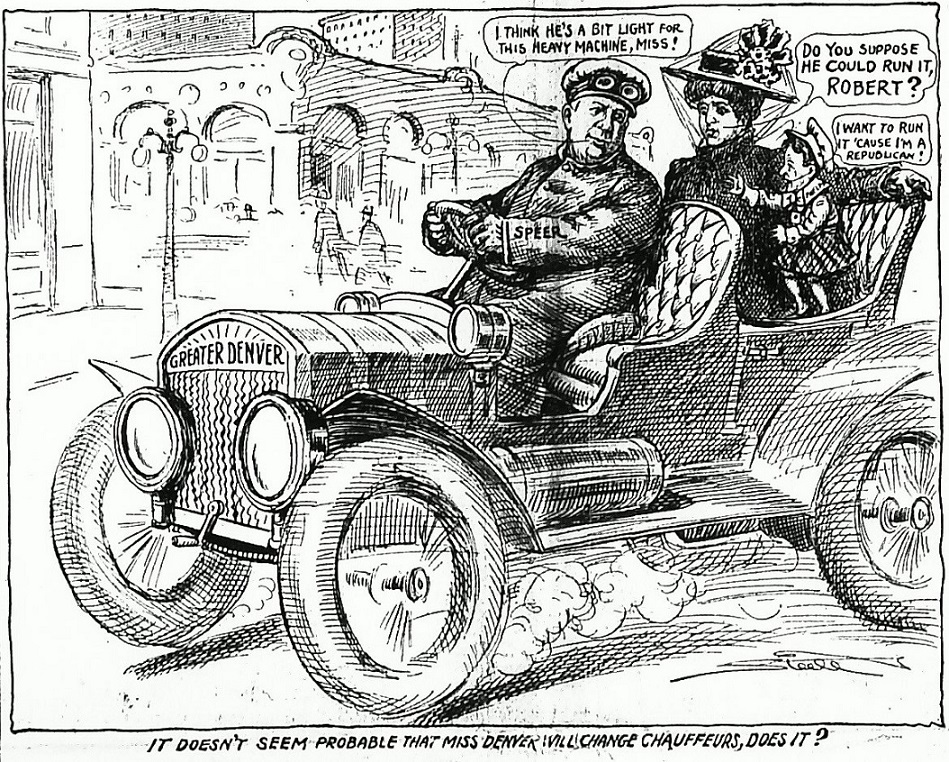

Doc. 8 Steele cartoon of Speer driving “Greater Denver” (1908)

Wilbur Steele drew this cartoon of Robert Speer when he was running for mayor a second time in 1908. The artist seems to have different ideas about Mayor Speer now.

[Source: Denver Post, April 28, 1908]

Questions:

- Here Steele has Mayor Speer behind the wheel of a car. It was considered a fancy car in 1908. What words appear on the front of the car? What might the car represent?

- Mayor Speer has two passengers. What do they look like? The caption at the bottom of the cartoon refers to “Miss Denver.” Who might that be? Can a person represent a whole city?

- The woman in the backseat asks Mayor Speer: “Do you suppose he could run it, Robert?” Remember that Speer’s first name was Robert. She seems to asking if the other passenger can run or drive the car. But what did the car represent?

- In the election for mayor in 1908, Speer was running against a man named Horace Phelps. Artist Steele included Phelps in this cartoon. Which one is he? Why did Steele draw Phelps that way? What did Steele want us to think about Phelps?

- Steele here drew Mayor Speer very differently from that first cartoon in 1904. How? Why might Steele have changed his mind about Speer?

- How might this cartoon influence voters just before the election?

***

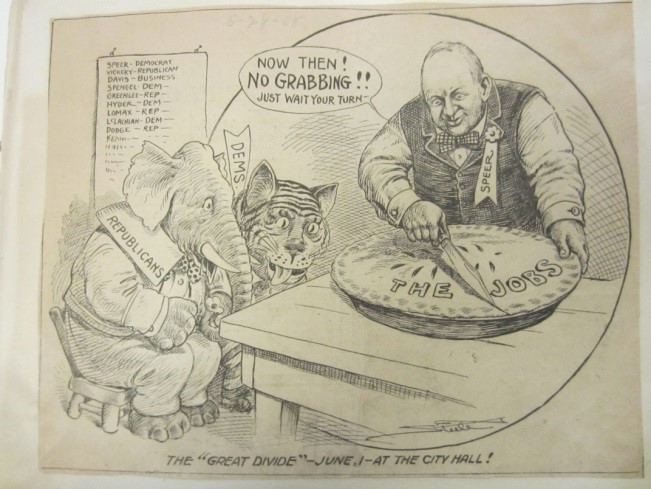

Doc. 9: Steele cartoon of Speer Slicing a Pie, 1908

Here is another Steele cartoon of Mayor Robert Speer. Notice the animals in the cartoon.

[Source: Denver Post (May 28, 1908)]

Questions:

- This cartoon appeared after Speer was elected mayor of Denver. Next to Speer are cartoon images of a tiger and an elephant. Each of those animals seems to represent a political party. Can you tell which ones?

- Mayor Speer is just starting to cut into a pie. What’s written on the pie? What might that mean?

- Do the tiger and elephant look scary in this cartoon? What kind of expressions do they have on their faces? In earlier cartoons, the tigers appeared quite dangerous. Why not in this one?

- What might the cartoonist want us to think about Mayor Speer and the two political parties?

- Does the cartoonist suggest in this cartoon that Speer is somehow violent or dangerous? Or does the artist Steele want us to think something else about Speer? What?

***

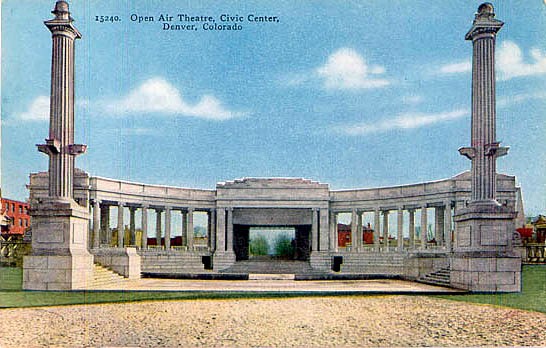

Doc. 10: Postcard Photograph of Denver’s Civic Center

While Mayor of Denver, Robert Speer oversaw the creation of the Civic Center in front of the state Capitol building. Here is a photograph of the theater created as part of the Civic Center project while Speer was Mayor of Denver.

[Source: “Penny Postcards from Colorado,” online at: http://www.usgwarchives.net/co/denver/postcards/ppcs-denver.html]

Questions:

- What was this theater made of? Was it cheap or expensive to build?

- This theater was designed for plays or concerts outdoors. What kind of music do you imagine people playing and listening to in this space?

- Mayor Speer is mainly remembered today for spaces in Denver like this one or Speer Boulevard. Have people today forgotten about the cartoons of Speer who stepped on “honest elections”?” Why or why not?

- If Speer made deals with bullies who cheated to win an election, does this Civic Center project help us feel better about him? Why or why not?

***

How to Use these Sources:

Option 1: This set of sources allows students to interpret images without many words to begin understanding the power of symbols. They might start with a discussion of a contemporary example of a symbol, maybe the school or sports team mascot. What does that symbol mean? Why did school leaders or students choose that image? Then students could turn to the Nast and Keppler cartoons of political leaders. Their main task here is to discuss why a cartoonist would draw a political or business leader in these symbolic ways? What message did that give?

After Nast and Keppler, two famous nineteenth-century cartoonists, students can consider the Colorado context. When Robert Speer first ran for the office of mayor of Denver in 1904, he made a few enemies. How did Wilbur Steele’s cartoon attempt to influence voters? What was Steele worried about with candidate Robert Speer?

Assessment Option 1: students might create their own political cartoons in answer to the question: how can cartoons influence people? First, the class could agree on a set of symbols that students might utilize to represent problems or concerns in their community or our current day. The historical symbols from these cartoons are of course options too! Then when individual students share a personal cartoon, the class could consider whether it captures a feeling that students share or just one that reflects an individual perspective. Is the picture worth a thousand words? If not, how many?

Option 2: Continue to cartoon interpretations with those from Wilbur Steele in Colorado. The cartoons included here suggest that Steele changed his mind about Speer. Why might he draw Speer so differently when he ran again for mayor in 1908 than when he first ran in 1904?

For this part of the lesson, students can apply some of their visual literacy skills from the Nast and Keppler cartoons. Symbols reappear in similar ways. Again, students can examine each cartoon source on its own before a discussion that compares them. The comparison can highlight how Steele’s views shifted and how differently a “friendly” cartoon of a leader appears from a more critical one.

Option 3: Students could compare these Steele cartoons with a twelve-page biography of Mayor Speer.

Stacy Turnbull, Robert Speer: Denver’s Building Mayor (Great Lives in Colorado History Series, 2011).

Questions for the biography and the Steele cartoons:

- The Speer biography has a chapter called “Life in Politics.” Here the author describes some of the ways that elections in Denver were connected to saloons and gambling. “Some people thought Speer’s ways of gaining power and influence were unfair,” wrote the author (4). What examples of this do you find in the book?

- What did the cartoon, “We do things to the Honest Voter,” suggest about Speer being unfair?

- In the biography chapter called “Mayor Speer,” the author describes many successes or accomplishments. Give three examples.

- Does it take away from all the good things Speer did as mayor to remember the sneaky tactics he used to get elected? Why or why not?

***

Additional Resources:

The internet offers a fantastic range of political cartoons from different political eras. Thomas Nast’s work is among the most accessible on the web. Harpweek.com features a wide and searchable selection of Nast cartoons that span his career. Thomasnastcartoons.com also offers comment on his famous cartoons. A recent biography, Thomas Nast: the Father of Modern Political Cartoons by Fiona Deans Halloran, provides much helpful background on this illustrator. The cartoons of Joseph Keppler, and other cartoonists who drew for his magazine, Puck, can be found at the Library of Congress (loc.gov) in the Prints and Photographs collection. For a biography of Joseph Keppler see: Richard Samuel West, Satire on Stone: The Political Cartoons of Joseph Keppler. Wilbur Steele lacks a biography, and his cartoons are harder to find. They appeared on the front page of the Denver Post from 1897 through 1925. They can be accessed via microfilm.

- For a good example of ballot frauds by both parties in 1904, see Marjorie Hornbein, “Three Governors in a Day,” in Steve Grinstead and Ben Fogelberg, Western Voices: 125 Years of Colorado Writing (Golden: Fulcrum Publishing, 2004) 116-133 or Todd Laugen, Gospel of Progressivism: Moral Reform and Labor War in Colorado (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2010), Chapter 1. ↵