7

Teacher Introduction

During the twentieth century different social groups in Colorado at times faced unequal treatment and discrimination. The dominant population of white Euro-Americans did not always welcome people of color or those immigrants who brought linguistic or religious diversity to the state. The question “Who fought for equality in Colorado?” recurs over the decades as different groups of Colorado residents insisted on civil rights and fair opportunities at key moments in history.

This chapter allows students to explore some important answers to that question about equality. Earlier chapters have highlighted the nineteenth-century struggles of Native Americans to maintain their homeland and way of live in the state. Here, students can focus on civil rights challenges among different immigrants and people of color in Colorado in the twentieth century. Many elementary students have begun to learn that Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks inspired a broad Civil Rights movement from the American South. Few know about similar struggles in and around the Rocky Mountains.

In 1895, Colorado legislators approved an important Civil Rights law that promised equal treatment of people in the state regardless of color or race. This law was meant to reinforce the Fourteen Amendment to the Constitution, which Congress approved in 1868. These legal protections of civil rights sadly would prove hollow in the American South as Jim Crow restrictions and legally mandated segregation became entrenched by 1900.

Racial and ethnic diversity in the Rocky Mountain West was different than in the South. Mexican Americans, Native Americans, African Americans, and Italian immigrants and their descendants were among groups that experienced who struggled to secure their rights. Although Colorado’s legal framework banned some forms of discrimination, the social reality for people of color did not always match the legal ideal.

During the 1920s Colorado witnessed the unexpected reawakening of the Ku Klux Klan. Some 35,000 native-born Protestant Euro Americans joined this nationwide social movement in that decade. Denver was the Klan capitol. In an unusual twist of its post-Civil War roots, this revived Klan broadened its targets to include not only African Americans but Catholic and Jewish immigrants as well. Religion became contested terrain as some bigoted Protestants insisted that theirs was the only patriotic religion in Colorado. Catholic and Jewish immigrants and native-born people of color resisted this narrow vision of public life in Colorado. Sometimes historians study racist groups like the Klan to try to understand them and their influence. This does not imply that historians approve or support their racism.

World War II marked an important shift. The loyal military service of people of color and the racist dictatorship of Nazi Germany offered new opportunities for civil rights activists to press the causes. Colorado witnessed a remarkable coalition of people of color who joined with white activists to press for civil rights. These struggles secured some important legal protections during the Cold War that followed. In 1957, Colorado legislators passed a cluster of important civil rights measures including a law to ban employment discrimination, a repeal of the ban on interracial marriage, and new enforcement provisions for the Public Accommodations law from 1895. Two years later, a Fair Housing Law was also approved. Historian Dani Newsum noted that by the late 1950s conditions for legal change were ripe at the state legislature:

“[T]he war service of men and women of color, combined with a stew of Cold War pressures, revulsion at the savagery of southern white supremacy, outside political pressure, and the insistent public education . . . of a sophisticated coalition of civil rights advocates had helped to transform most [Colorado] lawmakers perceptions of the government’s regulation of employment, marital, and consumer relationships.”[1]

Yet housing and school segregation continued into the 1960s. Those issues became the main battleground for civil rights activists.

For Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants, their civil rights struggle was not only about housing and educational opportunities. The descendants of the San Luis valley pioneers faced unfair treatment in schools and state government. Recent Mexican immigrant farm workers along the plains had to struggle as well to secure equal treatment in public accommodations. By the 1960s an influential Chicano movement had mobilized many in the Mexican American community in support of civil rights. Corky Gonzales was one of the movement’s leaders who affirmed a powerful Chicano identity for Colorado as well as other southwestern states. Combining Spanish Catholic traditions with indigenous Meso-American roots, the Chicana/o insisted upon belonging: “I am still here!” wrote Gonzales on behalf of this group. Chicana/o activists were quick to point out that their ancestors lived in Colorado long before statehood.

The sources in the chapter deal directly with inclusion and exclusion. Who was welcomed in Colorado? Who was not? How did those who faced exclusion or discrimination fight back? These are some of the questions that arise when students begin to confront the basic question—who fought for equality?

These sources do not, of course, tell the comprehensive story of exclusion, discrimination, and civil rights struggles in Colorado or the United States. They do offer a useful launching point for these issues and could easily stimulate additional research or investigation. At very least, they serve to introduce students to some key challenges of exclusion and struggles for inclusion in Colorado over the twentieth century. Additionally, Chapter Six on Immigration to Colorado confronts similar issues for other people of color.

We organized the sources in this chapter to reflect the idea of a K-W-L strategy. The first sources on Martin Luther King hopefully build on what students already know about Civil Rights Movement history and generate questions. Then sources will lead students to consider the Colorado context to find answers to their more regional history questions about Civil Rights.

***

Sources for Students:

Document 1: Statue of Dr. Martin Luther King and a new holiday, 1984

On January 20, 1986 Coloradans began observing a holiday in honor of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Here is a photograph of a statue of Martin Luther King atop a pedestal in City Park in Denver. The statue was created by artist Ed Dwight.

[Source: http://www.denver.org/things-to-do/denver-holiday-events/denver-mlk-day/]

Along with Rosa Parks, King is one of the most famous Americans in history. As a Civil Rights leader, Martin Luther King did not spend much time in Colorado. Still, our state government approved an official holiday to remember Dr. King. Below is an excerpt from that MLK holiday law:

|

WORD BANK: Reflect upon the principles: think carefully about the goals Espoused: promoted, talked about Appropriate: proper Observance: respectful celebration Commemoration: remembering positively |

This holiday should serve as a time for Americans to reflect upon the principles of racial equality and nonviolent social change espoused by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.; and…

[T]he Colorado General Assembly [will] coordinate efforts with cities, towns, counties, school districts…and with private organizations within Colorado in the first observance of the…legal holiday honoring Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

[T]he Colorado General Assembly hereby encourages appropriate observances, ceremonies and activities . . . to ensure the . . . commemoration of the . . . holiday honoring Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., throughout all the cities, towns counties, school districts and local governments within Colorado.

[Source: Colorado General Assembly, House Joint Resolution No. 1031 (1984)]

Questions:

- What do you know so far about Martin Luther King, Jr.?

- According to the law creating the Martin Luther King holiday, what goals did Colorado law makers have for this day?

- What kinds of groups did the legislators hope would work together on this holiday?

- What kinds of events do you think would help Coloradans think about racial equality?

- As far as you know at this point, did African Americans or Mexican Americans in Colorado have to fight for their rights? Or did they always feel welcome in Colorado?

- You can find many other pictures of the Martin Luther King memorial in City Park in Denver online. Find the best one you can if you can’t visit City Park in person. Does that statue help people reflect on racial equality? Why or why not?

- Do you know of other civil rights leaders who have statues in Colorado or in your local community?

***

Document 2: Colorado Civil Rights Law, 1895

In 1895 an African American lawyer representing Arapaho County in the Colorado legislature, Joseph Stuart, successfully promoted the idea of civil rights for all Coloradans. Civil rights include the idea that people should be treated equally in public places and free from discrimination because of their race or skin color. Here is an excerpt from the Civil Rights law that Stuart initially sponsored:

|

WORD BANK: Shall be entitled to equal enjoyment: will be able to make use of Accommodations and facilities of: spaces available in Regardless: without any talk about |

All persons within [Colorado] shall be entitled to…equal enjoyment of the accommodations [and] facilities of inns, restaurants, eating houses, barbershops, public [transportation], theaters, and all other places of public accommodation and amusement…regardless of color or race.

[Source: Colorado Session Laws, Tenth Session, 1895, Ch. 61. Civil Rights, p. 139.]

Questions:

- “Equal enjoyment of the accommodations” means equal opportunity to use and get into public places. If this law applies, can a white restaurant owner refuse to serve African Americans? Why or why not?

- Why do you think a law like this was necessary? What problems was it hoping to fix?

- The punishment for breaking this law was for the person guilty of discrimination to pay a fine of somewhere between $50 and $500 to the victim. How much should people who discriminate today have to pay such victims, in your view?

- Under this Civil Rights law local police were in charge of enforcing it. What might happen if the police did not investigate complaints of discrimination?

- What might someone do if they felt this law was not enforced and they faced discrimination anyway?

Document 3: Denver Star Report of Discrimination, 1913

Denver’s small African American community supported local newspapers in the early twentieth century including The Denver Star. The paper reported on successes and challenges faced by African Americans as they too hoped to realize the promise of life in this relatively new western state. While states like Mississippi and Alabama had passed laws that required segregation or separation of white and black people in restaurants, theaters, and schools, Colorado officially still had the Civil Rights law of 1895. Yet the Denver Star editor wrote in 1913:

|

WORD BANK: Cater to: do business with or serve Colored Trade: business with people of color Discrimination: unfair treatment |

Today along our public street these signs are printed and…displayed: “We cater to white people only,” at the Colonial Theatre, “Colored trade not wanted,” at the Paris theatre, a block apart on Curtis Street; around the corner on 18th street below Champa street, “White People’s Restaurant,”….All this discrimination within a radius of two blocks along the [main streets] of our city. What are we going to do about it?

[Source: “Denver Needs a Vigilance Committee: A Call to Arms,” Denver Star (September 30, 1913)]

Questions:

- What problems did African Americans face when they wanted to dine out or attend a show at a Denver theater?

- Why would white restaurant and theater owners put up signs like these? What would motivate them?

- These signs seem to contradict the 1895 civil rights law from document. What might African Americans in Denver do about that?

- Does it still matter if Colorado had a law against discrimination if discrimination happened anyway?

- Can the law help later on in some way?

***

Document 4: Photograph of women of Ku Klux Klan parade in Arvada, 1925

The Ku Klux Klan grew in popularity in Colorado and especially in Denver in the 1920s. By 1924, there were about 35,000 members in Colorado. Male and female members insisted that this was just a patriotic group, celebrating America. The often included flags in photos. But Klan leaders also threatened Catholic and Jewish immigrants as well as African Americans in Colorado. They tried to repeal the 1895 Civil Rights law. Their hooded costumes symbolized white racism from the American South after the Civil War.

[Source: Denver Public Library, Call # X-21548. Ku Klux Klan Ladies Auxiliary, 1925]

Questions:

- What kinds of people do you see in this photograph? Do they look dangerous?

- The hoods are lifted so that we can see their faces. Why do you think they didn’t cover their faces with hoods or masks?

- What else do you see besides these people in Klan robes and hats?

- What might those other symbols and people in the photograph mean?

- Who do you think the men in the back are supposed to be? What are they saying about the Klan?

- What might an African American leader do to protest the Klan in Arvada?

***

Document 5: Photograph of Whittier Elementary School Students, 1927

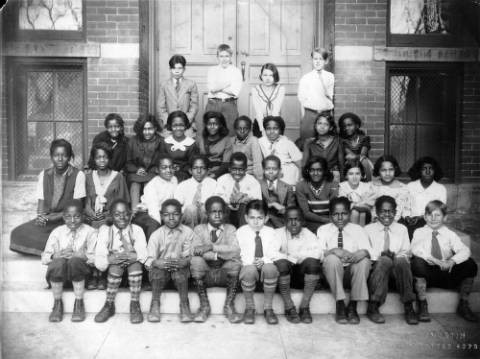

By the 1920s about ninety percent of Denver’s African American population lived in the neighborhoods called Five Points and Whittier, northeast of downtown. While this area included the homes, offices, and stores of doctors, dentists, lawyers, and many small businessmen, the residents of Five Points were limited by discrimination. African Americans were not able to buy houses in other neighborhoods. That meant that schools in Five Points and Whittier had large numbers of African American students. Here is a photograph of students at an elementary school in the Whittier neighborhood from 1927. These students would likely be headed for Manual High School which served this same neighborhood.

[Source: Denver Public Library Collection: https://history.denverlibrary.org/five-points-whittier-neighborhood-history]

Questions:

- How many African American students do you count in this picture? How many white students? Could there be Mexican American students here too?

- In Denver there were no laws that required black and white students to attend separate schools. Yet schools in neighborhoods like Five Points and Whittier had mostly black students and few whites. Why do you think that happened?

- Some African American parents in these neighborhoods wanted to move to different parts of Denver because they hoped for better school opportunities for their children. What might keep them from moving into mostly white neighborhoods?

- If they could not move into white neighborhoods, what might African American parents do to help their kids in poor schools?

- How do you think KKK Members from the previous document would feel about this photograph?

***

Document 6: Park Hill Neighborhood Flyer, 1932

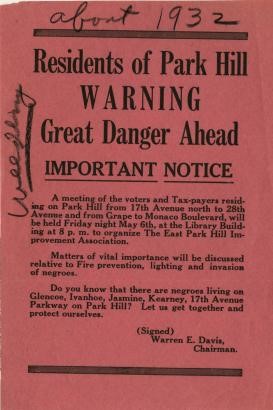

Park Hill was just to the east of the Five Points and Whittier Neighborhoods in Denver. People moved to Park Hill around 1900 to get away from the noisy city center of Denver. Homeowners and realtors (who help sell and buy houses) made agreements not to sell existing homes to African Americans. African American families could not buy houses in Park Hill in the 1920s because no white family or white realtor would sell to them. The flyer below appear about 1932.

[Source: Denver Public Library, “Great Danger Ahead” Flyer, call # C917.8883 R312 1932; “History of the Park Hill Neighborhood”: https://history.denverlibrary.org/park-hill-neighborhood-history]

|

WORD BANK: Residing: living Matters of vital importance: really important issues Relative to: related to |

Questions:

- This flyer was given out to Denver residents living the in Park Hill neighborhood. Where is that? Which Denver neighborhoods are to the west of Park Hill?

- Who is invited to the meeting? Why those people?

- A man named Warren E. Davis created this flyer to alert his neighbors in Park Hill to a “great danger ahead.” It’s not until we read the last paragraph that we can find the danger. What was it?

- Davis ends this flyer by suggesting that neighbors get together to “protect” themselves. Why would he use a word like “protect”?

- In what ways might white homeowners try to prevent black buyers from moving into their neighborhood?

- What makes this an example of discrimination?

- What might African American home buyers in Denver do about this?

***

Document 7: “No Mexicans” Signs Removed, Greeley, 1926

In 1901 the Great Western Sugar Company began growing and refining sugar beets near Greeley in northern Colorado. Mexican and Mexican Americans gradually began working in sugar beet fields. Many of the Hispanic workers moved into communities in and around Greeley. Here they faced discrimination and reminders that they were not thought of as equal to the white residents. “No Mexicans” signs in restaurants were an obvious example. The chamber of commerce was a group of business leaders asked to talk about these signs. Here is a newspaper story about those signs from 1926:

|

WORD BANK: Chamber of commerce: a group of business leaders in town Displayed: placed in a window Discriminatory: unfair |

[After] friendly discussions with the businessmen [of Greeley] the chamber of commerce has secured the removal of “No Mexicans” signs from practically all of the . . local business places which displayed them. The Spanish speaking people are very resentful of such discriminatory signs.

[Source: Greeley Tribune, (November 1, 1926). Quoted in Jody L. Lopez and Gabriel A. Lopez, White Gold Laborers: The Story of Greeley’s Spanish Colony (2007) 215.]

Questions:

- This newspaper story describes a change in Greeley. What were Greeley businesses doing before the change?

- Why do you think this change happened? What led business owners to take them down?

- This story appeared the same year as the Ku Klux Klan march pictured in document 4 above. From this story, could we make an assumption about whether the Klan was active in Greeley? Why or why not?

- Is this newspaper story enough for us to claim that Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans no longer faced any discrimination in Greeley after 1926? Why or why not?

- How could we find out if this was a temporary change for the better or a long-last one for Mexican Americans in Greeley?

Document 8: Corky Gonzales, “I am Joaquín,” 1967

By the 1960s, Mexican Americans protested discrimination and the lack of opportunities for their community. Mexican America parents and students did not accept racism in the public schools. The police at times harassed and even killed young Mexican Americans who were not dangerous. Activists were also inspired by the black civil rights movement led by people like Martin Luther King, Jr. In the poem below, Denver activist Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales expresses frustration and hope for Mexican Americans:

I am Joaquín

Lost in a world of confusion,

Caught up in a whirl of a gringo society.

Confused by the rules,

Scorned by attitudes . . .

My fathers have lost the economic battle

and won the struggle of cultural survival . . .

Here I stand,

Poor in money, arrogant with pride,

Bold with machismo, Rich in courage

And wealthy in spirit and faith.

My knees are caked with mud.

My hands calloused from the hoe.

I have made the Anglo rich, yet

Equality is but a word….

I have endured in the rugged mountains of our country

I have survived the toils and slavery of the fields.

|

WORD BANK: whirl: spinning gringo: a person who is not Hispanic or Latino scorned: feeling worthless economic battle: struggle to make enough money for success cultural: having to do with a group’s language, religion, and traditions survival: staying alive machismo: male toughness calloused: hardened skin patches from hard work Anglo: Mexican American word for white Americans rugged: uneven and rocky toils: very hard work |

I have existed

In the barrios of the city

In the suburbs of bigotry…

In the prisons of dejection…..

I am the masses of my people and

I refuse to be absorbed

I am Joaquín….

I WILL ENDURE!

|

WORD BANK: barrios: neighborhoods where Mexican Americans live bigotry: intolerance for someone different dejection: feeling sad and depressed |

Questions:

- What words or phrases did the poet use to describe Joaquín?

- What kind of work did Joaquín do?

- Joaquín is obviously a boy’s or man’s name. But the poet here seems to use that name to represent other people. What people? How does he use the name Joaquín to mean other people?

- “Endure” and “survive” appear in the poem more than once. Why?

- How did Gonzales write about hope?

- In what ways did Joaquín feel excluded in this poem?

- What could change to help Joaquín feel like he belonged in Colorado?

***

How to Use These Sources

This collection of sources offer students a chance to approach civil rights by considering exclusion and inclusion. When in Colorado history did different groups face exclusion? How did those excluded groups respond and fight to belong? These are of course broad questions, but students can begin to address them here to create a context for the twentieth century history of civil rights.

Option 1: Students could start with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and document 1. This will likely be familiar territory for many students and can help build a context for exploring civil rights. How best should we today celebrate and honor the legacy of Dr. King? Don’t worry if students do not yet know about specific national details like the Montgomery Bus Boycott or the Little Rock Nine or Selma. The Colorado connection to Dr. King can be useful as a starting point for thinking about discrimination and civil rights.

Then students could begin to create a context for the civil rights struggle in Colorado. What are civil rights? The teacher might start an on-going list. The Civil Rights Law of 1895 offers a promise and a kind of test for later generations. Keeping in mind the main question of equality, students could discuss how this law expressed a hope that different Colorado residents belonged in public places. Civil rights are not easily understood by students, even though they quickly learn that Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks were civil rights heroes. Over the course of the lesson, students could expand their list of civil rights and freedoms as they find them in the documents.

Following those initial documents, students in groups could consider cases that tested the first promise of equal treatment in that 1895 law. Documents on restaurant and theater discrimination as well as the housing restrictions in Denver suggest the limits of that 1895 promise of inclusion. The contract between law and reality on the streets of Denver is painful but important for students to understand. America has always been a country of great promise. What happens when the reality falls short for people of color? Here student can expand on their list of civil rights. Mexican American discrimination in Greeley, and the poem “I am Joaquín” provide additional examples of exclusion. In each case, certain groups wanted to challenge exclusion and insist that they belonged in Colorado. Students could answer the questions on each source in small groups and then discuss as a class what it meant to belong in each case. How did these excluded groups want to belong? How did they protest or push for inclusion?

Option 2: After completing the work in Option 1, students could turn to the issue of change over time. How did Colorado get from exclusions and discrimination that we see in these documents to a holiday and statues honoring Dr. Martin Luther King? This is not to suggest that racism no longer exists in Colorado or the United States. But students could consider if there have been improvements and a larger movement toward fairness over time. Of course, they will not be prepared at this point to provide a detailed explanation of that change over the twentieth century. But they will have valuable ideas about how this happened. This lesson could provide though a helpful introduction to questions of exclusion, inclusion and civil rights. What caused this change over time?

Option 3: Write a poem about identity in light of this historical story. What makes who you are? Has your family faced challenges or exclusions that shaped who you are? How are your family’s challenges similar to or different from those in this chapter?

Additional Resources:

Denver Public Library, “Five Points-Whittier Neighborhood History,” at: https://history.denverlibrary.org/five-points-whittier-neighborhood-history

Great Lives in Colorado History Biographies. This elementary-level biography series includes bi-lingual English/Spanish titles on Justina Ford, Corky Gonzales, Chin Lin Sou, Barney Ford, and Clara Brown.

Dani Newsum, “Lincoln Hills and Civil Rights in Colorado,” Primary Source Set available at HistoryColorado.org.

- Dani Newsum, “Cold War Colorado: Civil Rights Liberals and the Movement for Legislative Equality,” (MA Thesis: University of Colorado, 2012), n p. 171 ↵