2

Teacher Introduction:

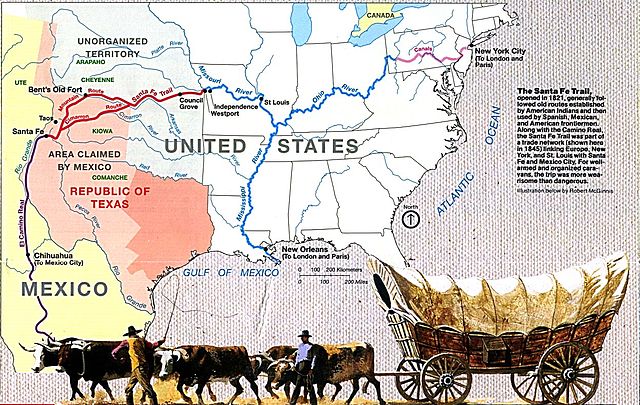

The earliest inhabitants of the mountains and plains that became Colorado were of course Native Americans, such as the Utes. The Northern Cheyenne and Southern Cheyenne moved west into the area that became Colorado in the early 1800s. When William Bent created his successful trading post in 1833, he relied on a partnership with the Southern Cheyenne. The Santa Fe Trail became a major conduit for trade after Mexico’s independence from Spain in 1821. Euro-American fur trappers in the north began interacting with native peoples in these decades as well. Colorado became a U.S. territory thirteen years after the U.S.-Mexico War (1846–1848). By 1850 Spanish-speaking settlers ventured into the San Luis Valley. They also moved onto the plains south of the Arkansas River. There they encountered various Ute bands as well as Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, and Comanche peoples. The establishment of the Overland Trail near the Nebraska and Wyoming borders led to more contact and violence among new settlers and native inhabitants during the 1860s. (Maps of trails can be found online). The Gold Rush of 1858–1859 launched a tremendous wave of Euro-American migration to new mountain settlements as well as Golden and Denver. African Americans and Asian immigrants also joined this movement into the lands that would become Colorado. These new settlers increased cultural and racial diversity in the territory.

This chapter focuses on that diversity by comparing the experiences of some settlers in Colorado in the 1800s. When Colorado became a U.S. territory in 1861, there were over 30,000 new residents and thousands of native peoples in the area. Most of the Euro-Americans moving to Colorado in these years were single, male, white miners. We explore the miner experience in a separate chapter. But here students can consider the lives of more diverse early residents to get a sense of the multiple paths that they pursued in attempting to earn a living in this territory and state. Many who came before the Gold Rush arrived by or had a connection to the Santa Fe Trail or New Mexico. This chapter invites students to consider a broader range of pioneers in different regions of Colorado.

Initially, students can explore the lives of William Bent and his Southern Cheyenne wife, Owl Woman. Moving from St. Louis, Bent established a fur trading post on the Arkansas River in the 1830s to supply travelers along the Santa Fe Trail. Owl Woman was part of a prominent Southern Cheyenne family. Their twelve-year marriage represented a connection between the white world of traders and fur trappers and the Cheyenne world. Their four children also lived between these two worlds, even as the Colorado Gold Rush and the tens of thousands of white miners and settlers began building cities and roads and farms in the territory. As conflicts between the Cheyenne and white settlers increased in the 1860s, William Bent attempted to make peace. He negotiated between the two groups in hopes of avoiding open warfare. His efforts failed, however, and his children were caught in the violence and forced to choose sides.

Next, this chapter includes primary sources on San Luis Valley pioneers. These 1850s settlers from New Mexico brought important Hispanic traditions to this southern Colorado region. They organized plazas with farm land stretched out in narrow bands along key waterways in this arid region and dug the first irrigation ditches in the territory. As Spanish speakers tied to the Catholic culture of Mexico, these people established different settlement patterns from other pioneers.

Students will also encounter sources on diverse women pioneers. An ex-slave from Kentucky, Clara Brown, joined early gold seekers and helped establish Central City. Her arrival came later than Bents or the San Luis Valley pioneers, but her community established important patterns that recurred in other gold and silver rushes across the mountains. White women like Emily Hartman and Ella Bailey confronted important challenges and demonstrated significant resilience in their pioneering experiences. Last, students can read about a ten-year-old child’s perspective on moving into his first Colorado home in 1906. All of these experiences can help students answer the central question: What did it take to be a pioneer?

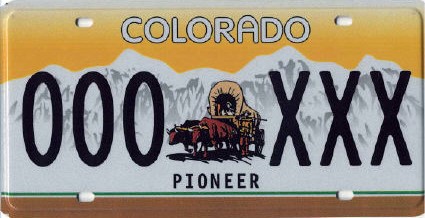

As Colorado’s recent Pioneer license plate indicates, many people think of pioneers as white families moving west in prairie schooners. Or the term may evoke an image of the lone, male prospector roaming the Rocky Mountains. The historical experience did include those people, but Colorado included so much more. With this chapter, students can explore this question about pioneering from multiple perspectives and begin to reconstruct the diverse lives of early settlers. They also can begin to compare source fragments to reconstruct pioneer life.

***

Sources for Students:

Doc. 1: William Bent Photograph, 1867

William Bent (1809-1869) was born in St. Louis, Missouri, one of eleven children. Following his older brother’s example, William moved west along the Santa Fe Trail in 1829 in search of adventure and a chance to make money. This trail connected St. Louis, Missouri, with Santa Fe and ran through lands that later became Colorado. Here is a recently created map of that trail.

William Bent developed a friendship with the Southern Cheyenne. In 1833 he built a fort along the Arkansas River. This fort allowed Bent to supply travelers along the Santa Fe Trail. Cheyenne and Arapaho peoples also traded at the fort.

To secure his connection to the Cheyenne, William Bent married the daughter of chief White Thunder in 1835. Owl Woman, or Mis-stan-sta, and William Bent lived in the fort part time. They also lived with the Cheyenne in their buffalo-hide tipis. Bent’s connections to the Southern Cheyenne and Southern Arapaho helped make his trading post along the Santa Fe Trail very successful.

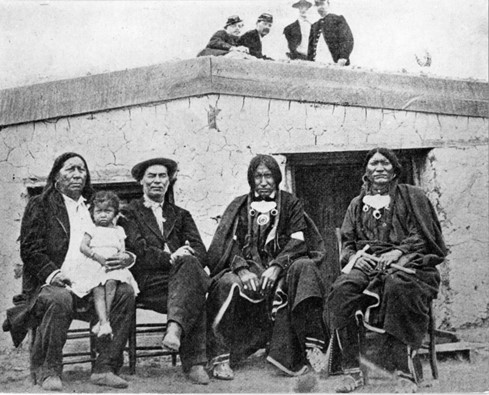

Here is a photograph of William Bent (with a hat) sitting between Southern Arapaho chief Little Raven and his sons. Little Raven holds his granddaughter on his lap:

[Source: History Colorado. Available online at: http://www.coloradovirtuallibrary.org/digital-colorado/colorado-histories/beginnings/william-bent-frontiersman/]

Questions:

- How are the clothes of each person alike or different? Why might the clothes be alike or different?

- Can we tell from the picture if Bent was friends with these other men?

- Who could the men at the top of the photograph be? What details make you think so? Why might they be in this picture?

- Based on this picture, what can we learn about William Bent and his relations with the Southern Arapahos?

***

Documents 2 and 3 about Bent’s Fort should be paired

Doc. 2: Photo of courtyard of Bent’s Fort after its reconstruction in 1976.

For sixteen years, Bent’s Fort was the only major Euro-American settlement between Missouri and New Mexico. Bent built the fort on the north bank of the Arkansas River near the current town of La Junta. Travelers on the Santa Fe Trail would stop here for supplies. They met fur trappers and different Native Americans in the fort. In 1849 Bent’s Fort burned to the ground. The National Park Service rebuilt the fort more than 125 years later. Builders used paintings and drawings of the original fort along with parts of the fort that were still there. Here is a photograph of the inside of the rebuilt fort:

[Source: Library of Congress photograph: https://www.loc.gov/item/2015632789/]

***

Doc. 3: Visitor to Bent’s Fort in 1839

The next document gives us a description of life in Bent’s Fort from a visitor who met Bent. Matthew Field was a newspaper reporter. He stopped at Bent’s Fort in 1839. He described what he saw inside the fort:

Two hundred men might [sleep] . . . in the fort, and three or four hundred animals can be shut up in the corral. Then there are the store rooms, the extensive wagon houses, in which to keep the enormous heavy wagons used twice a year to bring merchandise from [St. Louis], and to carry back the skins of buffalo and the beaver….[The many rooms enclosed in the walls] strike the wanderer…as though an ‘air built castle’ had dropped to earth…in the midst of a vast desert.

[Source: John E. Sunder, ed., Matt Field on the Santa Fe Trail (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1960), 144. ]

|

WORD BANK: Corral: a place to keep large animals Merchandise: items to buy Enclosed: inside Strike: appear to Midst: middle Vast: great big |

Questions:

- How many men and how men animals were there at Bent’s Fort when Field visited? How might that smell, at a time before there was indoor plumbing for showers and toilets?

- According to Matthew Field, how might it feel to stay at this fort?

- What noises might a visitor to Bent’s fort in 1839 have heard?

- With these two sources, we can imagine what the inside of the fort might have looked like. What sort of work or jobs do you think people did in the fort? Why?

- How did Bent make money to keep this fort going?

- Find Bent’s Fort (or La Junta) on a map of Colorado. Imagine riding on horseback or walking from St. Louis, Missouri to Taos, New Mexico. This fort was the only settlement along that route. How long might it take you to reach Bent’s Fort from St. Louis if you traveled miles by horse at 10 miles per hour?

- How did William Bent succeed as a pioneer?

***

San Luis Valley Pioneers: The next two documents are paired together

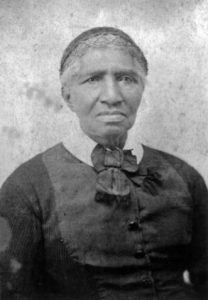

Doc. 4: Photo of María Eulogia Gallegos, 1860s

María Eulogia Gallegos was a pioneer settler in the San Luis Valley. Here is a photograph of María Eulogia Gallegos from the 1860s:

[Source: Denver Public Library Digital Collection. Call # AUR-2247]

She came from Taos, New Mexico and married Dario Gallegos in 1850. They were two of the founders of the town of San Luis in the early 1850s. They were in Colorado before the Gold Rush. She and Dario had nine children.

Together they started a store that sold merchandise such as groceries and hardware. At first they supplied the store by sending horse-drawn wagons over the Santa Fe Trail from St. Louis, Missouri. Those wagons would have passed the site of Bent’s Fort. They sold to American soldiers at Fort Garland to the north. Ute Indians and San Luis settlers also traded at the store.

One of María and Dario’s daughters married the son of another San Luis settler, Arcadio Salazar. After Dario Gallegos died in 1883, this daughter and son-in-law ran the store. Their son, Delfino Salazar, continued the tradition. The store nearly closed in 2017 after more than 150 years in business.

Doc. 5: Interview with María Eulogia Gallegos’s son and grandson, 1933

In 1933 the US government paid for writers to interview Colorado pioneers. Charles Gibson interviewed Gaspar Gallegos and Delphino Salazar. They were the son and grandson of María Eulogia Gallegos and her husband Dario. The two men told Gibson about the early days of San Luis and their ancestors, Dario and María Eulogia Gallegos:

“When Dario died he left a great deal of [farm] property including twenty-six thousand head of sheep, and although Mrs. Gallegos could neither read nor write she became a very able manager. Gaspar recalled that when he was a small boy his mother raised a great many chickens and he used to go with her to [US Army] Fort Garland, where they were sold to the officers. She would take only silver, one piece of money for one chicken, either twenty-five cents or ten cents.”

“According to [María’s grandson], San Luis, Colorado and Boston, Massachusetts, are the only towns in the United States having a ‘Common,’ especially set aside for the use of the people. Carlos Beaubien donated the meadow just west of the town to the people . . . . In this way a convenient pasture was assured [and shared] for the horses and milk cows of the San Luis residents.”

[Source: Civil Works Administration Pioneer Interview Collection, volume 349, interview 28, pp. 105–6, recorded by Charles E. Gibson Jr. in 1933 or 1934. Available online at HistoryColorado.org]

|

WORD BANK: convenient: nearby assured: available for sure |

Questions on these sources:

- What do you notice in the photo of María Gallegos?

- According to María Gallegos’s son Gaspar how did his mother make money? Was it a problem that she could not read or write?

- The town where María lived, San Luis, had a “common.” What could San Luis residents do with that space? Why wasn’t that area owned by just one person?

- Farming and ranching were important to many in San Luis. What kind of work did María, Dario, and their children likely do to keep the farm and ranch healthy and successful?

- How did María Gallegos succeed as a pioneer?

***

Doc. 6: Record of the founding of Guadalupe, CO (1933)

In 1933, the US government paid writers to interview Colorado pioneers and their children. One of these writers was Charles Gibson. The son of a pioneer settler, Jesus Velasquez, wrote down a short history of the founding of Guadalupe for Gibson. Velasquez probably heard this story and learned the list of the town founders from his father, Vincente Velasquez. The story is not complete though. You will have to help fill in some missing information.

Founders of the town of Guadalupe, 1854

| Jose Maria Jaquez, leader | El Llanito, New Mexico |

| Vincente Velasquez, 15 yrs. Old | El Llanito, New Mexico |

| Jesus Velasquez | La Cueva, New Mexico |

| Jose Manuel Vigil | La Cueva, New Mexico |

| Jose Francisco Lucero | La Servilleta, New Mexico |

| Juan Nicolas Martinez | La Servilleta, New Mexico |

| Santiago Manchego | La Cueva, New Mexico |

| Juan de Dios Martinez | La Cueva, New Mexico |

| Antonio Jose Chavez | La Servilleta, New Mexico |

| Juan Antonio Chavez | Ojo Caliente, New Mexico |

| Ilario Atencio | Ojo Caliente, New Mexico |

| Juan de la Cruz Espinoza | Ojo Caliente, New Mexico |

“All of the above named persons came to settle on what is called Conejos River. They came in August 1854 and stopped about 5 miles west of Guadalupe. They build a ditch from this point which they called El Cedro Redondo . . . . They build this Ditch for about 8 to 10 miles long to [a place] they called Sevilleta. Then they went back to their homes in New Mexico . . . to get ready . . . so that they could stay [in Colorado] when they came back.

|

WORD BANK: Livestock: animals raised for food or work Arms: guns |

“They came back in October 1854. They stopped at Guadalupe [and] here they built a town. They built it in a circle with only two openings: one on the south and one on the north. Here they put what livestock they had for fear of the Indians which were in great numbers at that time. They had come on ox carts and burros [from New Mexico]. They brought with them wheat, corn, flour, beans, cattle, horses, sheep, hogs, and chickens.

“But in March 1855 they had bad luck. One morning as they drove their livestock to pasture the Indians came from an ambush and [took] all the animals that the people had. The people had no arms to fight with and the Indians were too many for the people. So the Indians took all of the people’s animals.”

[Source: Civil Works Administration Pioneer Interview Collection, volume 349, interview 10, pp. 40–41, recorded by Charles E. Gibson Jr. in 1933 or 1934. Available online: https://www.historycolorado.org/oral-histories]

Questions:

- We have a story here about the creation of a town called Guadalupe in the San Luis Valley and a list of names. Why are there names of men listed at the beginning? What might the names of towns to the right of those men mean?

- What details do we learn about the creation of Guadalupe from this story?

- Why do you think these settlers spent time digging a ditch before they built the town?

- How did these San Luis settlers hope to thrive in this new town?

- What bad luck happened to them?

- How might it help to create a new farm with a community of people, rather doing it alone or just with one family?

The next two sources focus on a pioneer named Clara Brown

Doc. 7: Photograph of Clara Brown, about 1875

Clara Brown was born a slave in Virginia around 1800. Here is a photograph of Clara Brown around 1875:

[Source: Denver Public Library Digital Collections. Call #Z-275]

Growing up a slave, Clara Brown was married at eighteen and had four children. Her family was broken up when her white master sold her husband and children to other white owners. She spent the rest of her life to trying to find her family.

Clara became free when her master, George Brown, died in 1856. Hearing that one of her daughters had moved West, Brown eventually walked with a covered wagon train to Denver in 1859. She was one of the first African Americans in Colorado. Brown opened a laundry service in the gold rush town of Central City. After a few years, she had saved thousands of dollars. She often helped homeless and sick miners who needed a place to stay. She was admired by the mostly white population of Colorado Territory for her generosity and kindness.

Docs. 8 A and B: Newspaper reports of fire in Central City, 1873

Clara Brown did not leave behind her own story of her life. She did leave a few sources of information that we can use to understand her life and experience. One place we can look for information about Clara Brown is the newspapers in the towns where she lived. Here is a newspaper story about a fire that mentions Clara Brown. Consider how reading this newspaper can help us find out more about her.

Story 8A: “The line of buckets was extended up Lawrence Street while another was brought from a shaft upon the hill and a desperate effort made to save the building which had become ignited from the burning chapel on the west. This however failed and three small buildings belong to Aunt Clara Brown (colored) were soon wrapped in flames.”

[Source: “Our City in Flames!” Daily Register Call, January 28, 1873.]

|

WORD BANK: Line of buckets was extended up: people in town formed a line to pass buckets of water Shaft: opening of a mine |

Story 8B: “The losses, as near as we have been able to [tell], are as follows….Clara Brown, three houses, $1800.”

[Source: “The Late Fire in Central,” Daily Colorado Miner, January 29, 1873.]

Questions:

- Look at the photo of Clara Brown. What five words describe her?

- Does a photo like this help us imagine what Brown was like? Why or why not?

- What do we learn about Central City in 1873 from these newspaper stories in the Daily Register Call?

- How many houses did Clara Brown own, at least?

- Can we tell whether her laundry business had been successful? Why or why not?

- What might she do after this event in 1873? Might she be discouraged?

- How could we find out what happened to Clara Brown after this fire?

- How did Clara Brown succeed as a pioneer?

***

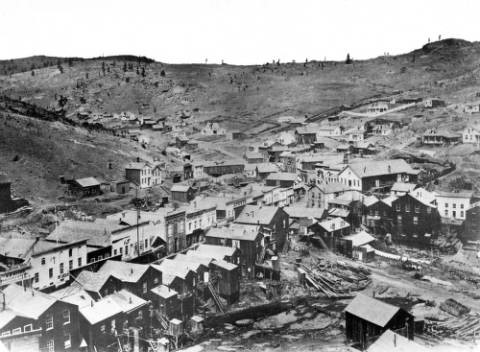

Doc: 9: Photograph of Central City in 1875

[Source: Denver Public Library, call # X-11588. Available online at: http://digital.denverlibrary.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15330coll22/id/9632/rec/290]

Questions:

- This photograph of Central City was likely taken after the fire. This was the main street. What might it feel like to walk that street in 1875?

- This was a town that supported gold miners in the surrounding hills. What kinds of stores and businesses might those miners need?

- Do you see any trees on the hills around the town? How might town settlers use trees in this area?

- How would you describe this town that Clara Brown lived in?

Doc. 10: Interview with Emily Sudbury Hartman, 1934

Emily Sudbury Hartman was born in Utah to Mormon parents in 1859. Her mother divorced Emily’s father and later married a U.S. Army soldier at Ft. Bridger. Emily was only seven years old in 1866 when her family moved to Denver. After she finished school, Emily trained as a nurse. She later helped run a sanitarium, a kind of hospital, with her husband, Flavius Josephus Hartman. He was raised in Kansas and came to Colorado to join his father who had come for the Gold Rush.

In 1934, Emily sat down with a US government interviewer and told him about their early days in Colorado:

“[In 1866 Emily’s family] was just becoming accustomed to the use of kerosene lamps instead of candles. [Emily’s] mother purchased one of the first hand sewing machines put on the market. Apples were brought into Denver from Missouri in Prairie Schooners, and sold at very high prices.

WORD BANK:

Accustomed to: used to, familiar with

Prairie Schooners: covered wagons

Tallow: animal fat

She was married to Flavius Josephus Hartman in 1877, after going [with him] to the San Luis Valley . . . . [Her husband’s father] had come into Colorado in 1859 with the Pike’s Peak gold rush, leaving his wife and several children on a ranch in Kansas. One time when the mother had gone to town [for food], a severe blizzard came up and she could not get back for three days. The three boys that were left behind [stayed alive] by burning the fence and grinding corn in the coffee grinder, making griddle cakes and cooking them in grease from tallow candles.

This little family suffered severe hardships because they were deprived of . . . money sent by the father from Colorado [when a mail clerk stole it] . . . . At the age of sixteen years [Flavius Josephus] was washing dishes and waiting tables in a restaurant in Denver. At that time eggs were twenty-five cents apiece and flour was twenty dollars a sack.”

|

WORD BANK: Severe: very hard Hardships: difficult challenges Deprived of: robbed of |

[Source: CWA Pioneer Interview of Emily Sudbury Hartman by Arthur W. Monroe, (February 3, 1934) v. 357 pages 6-8. Available online: https://www.historycolorado.org/oral-histories]

Questions:

- How far did apples have to travel by horse-drawn wagon to reach Denver in 1866?

- Emily describes a big challenge her husband faced when he was a child. What happened to his family?

- What kinds of skills might her husband have developed as a child in Kansas before he came to Colorado?

- Who might Emily Sudbury Hartman have met in the San Luis Valley?

- How might we find out whether the price of eggs or the price of flour was expensive back then?

- Why do you think this Colorado pioneer story mentioned food so often?

***

Doc. 11: Ella Bailey Diary, 1869

Ella Bailey ran a boarding house near Greeley in 1869. That means she had to cook and clean and wash clothing for men who rented rooms from her. She kept a diary and recorded these entries about some of her days in the winter of 1869:

“Sun. Feb. 7: “[T]he days are 48 hours long in Colorado and Sundays seventy two hours long.”

“March 2: Baked fifty one pies. Tired as a beggar.

“March 3: Baked twenty three pies and three thousand cookies and ginger snaps.

“March 6: If men was company to me like friends at home, I would never get lonesome.

“April 8: I can’t help but wish I had never seen Colorado. It is lonesome and desolate.

[Source: Ella Bailey Papers (1869) History Colorado, Mini-MSS #28]

|

WORD BANK: Beggar: A very poor person who begs for change or food Desolate: a place without people. |

Questions:

- According to Ella Bailey, how long are the days in Colorado? How long are Sundays? Why would she say something that cannot be true?

- How much cooking and baking did Ella do on the first two days she wrote about? How did she feel afterward?

- Does she have much company at the boarding house? Why or why not?

- Why would Ella stay and keep working at this place? Do you think that she is alone?

- What did Ella Bailey do to succeed as a pioneer?

***

Doc. 12: Ralph Moody, 1950

Ralph Moody moved as a boy from New England to a ranch near Littleton in 1906. His family of seven hoped to find a working farm when they first arrived. Here is how Ralph described what they first saw when they reached their new ranch:

“We could see our new house from a couple of miles away . . . . [I]t looked like a little dollhouse sitting on the edge of a great big table . . . . As we came nearer, it looked less like a dollhouse and more like just what it was: a little three-room cottage . . . . The chimney was broken off at the roof and most of the windows were smashed. When we turned off the wagon road, a jack rabbit leaped out from under the house and raced away . . . . There wasn’t much to see [inside], except that the floor was covered with broken glass, and plaster that had fallen off the walls and ceiling . . . .

|

WORD BANK: Cottage: a small home Plaster: a material spread over walls and ceilings to make a hard cover Bargain: an item bought at a lower price than expected Privy: a toilet outside the house |

“[My father and I] got up before daylight every morning for the next two weeks . . . First we’d pick up any of the bargains Mother had found for the house, then buy secondhand lumber, plaster, glass, and other things we needed on our way out to the ranch. And father would never stop working till it was so dark he couldn’t see to drive a nail.

“[After about a week] Father had built a new chimney, patched the places where the plaster had fallen off, put glass in all the windows, and made the front and back steps for the house. My part of the job was to sweep up all the broken glass and plaster . . . . There was nothing left to build but the privy.”

[Source: Ralph Moody, Little Britches (1950) pps. 3-5.]

Questions:

- How did Ralph’s house look when he and his family first arrived there?

- Why do you think it looked like that?

- Why do you think his mother and father didn’t just turn around and go home right off?

- What did Ralph and his father do to help make their home liveable?

- What kinds of skills might Ralph have learned from watching and working with his father?

- How would those skills help a pioneer?

***

Doc. 13: Pioneer License Plate, 1999

Remembering the experiences of Colorado pioneers has been important for many generations in the state. To take only a recent example: starting in 1999 the Colorado Department of Motor Vehicles introduced a new license plate to allow residents to celebrate their ancestors who had arrived in the state more than one hundred years earlier.

At first, people who wanted this license plate had to prove their family connection to a Colorado resident from at least 100 years ago. Now anyone can request this license plate if they pay an extra fee.

Questions:

- What images do you see on this license plate?

- Why do you think the state officials chose those images?

- What other images of pioneer life could appear on a license plate like this?

- If this Pioneer license plate included key words to describe pioneers, what would they be?

***

How to Use these Sources:

OPTION 1: Comparing Pioneer Communities.

Beginning with the William Bent documents, students could compare these first three sources to recreate some key aspects of his pioneer life. His story can help situate the white pioneer experience in the context of Native Americans. Students could answer the question: what kind of community did Bent help create along the Arkansas River in the 1830s? After reviewing these Bent sources, students could turn to those dealing with the San Luis Valley. Here students can read and interpret sources about early Hispanic settlers. After exploring each of these sources individually, students could describe the kind of community that emerged in the San Luis Valley in the 1850s. They could then compare that to the Bent’s Fort community. Maps from the previous chapter could be used to find these places.

OPTION 2: Pioneers after the Gold Rush.

The remaining sources describe pioneers who came to Colorado during or after the Gold Rush. Though many pioneers were single, male, white miners, Clara Brown offers an important alternative experience. Students can review the sources to begin to understand how this hard-working African American woman became successful in a mining boom town even though she was not a miner. We have little information directly from Clara Brown, and so must instead look at fragments or pieces of information to reconstruct her life. Included here are two newspaper stories about a fire that help us understand her real estate holdings and success as a business woman. The Clara Brown, Emily Hartman, and Ella Bailey sources give us a picture into the lives of other pioneering women in Colorado. The Ralph Moody source gives a child’s perspective on pioneering, though later than the Gold Rush. After exploring these individual sources, students could compare them to create a list of hardships and resilient characteristics. All these pioneers displayed a kind of toughness and determination, but they did so in different ways.

OPTION 3: Pioneer License Plates.

After reviewing all the previous sources, students can turn to the pioneer license plate. They can consider what images help tell the story of a Colorado pioneer. After reviewing the state of Colorado’s official plate, students could create their own plates to honor one of the pioneers from this chapter or to remember key aspects of the pioneer experience. Or their individual pioneer license plate could include a list of key characteristics or images to reflect the diversity of these experiences.

***

Additional Secondary Sources for Younger Readers

There are many short biographies of Colorado pioneers available for elementary-level readers. Some recent examples include:

- Cheryl Beckwith, William Bent: Frontiersman (Palmer Lake: Filter Press, 2011)

- Emerita Romero-Anderson, José Dario Gallegos: Merchant of the Santa Fe Trail (Palmer Lake, CO: Filter Press, 2007)

- Suzanne Frachetti, Clara Brown: African American Pioneer (Palmer Lake: Filter Press, 2011)

- The online Colorado Encyclopedia also includes short biographies of many pioneers (http://coloradoencyclopedia.org/).