3

Teacher Introduction:

Some of Colorado’s earliest visitors and settlers came for the Pike’s Peak Gold Rush. Starting In late 1858, many men from other states and territories heard that they could find gold in the streams and rivers flowing through the Rocky Mountains. This was a decade after the first major American gold rush to California. Some Colorado prospectors were in fact frustrated ‘49ers looking for a second chance. The Colorado prospectors helped found the first major mining district in the area that would later become Central City. Prior to being used for mining, these high altitude zones were familiar and important places for Ute Indian bands along with elk, antelope, moose, and marmots. After 1859 these districts began to fill quickly with crowds of men hoping for a lucky strike. Colorado gold rush pioneers soon found that most gold was in fact not easily scooped up from the water or picked up off the ground. The abundant gold and silver in the Rocky Mountains was locked deep underground and tightly bound to other rocks and minerals. Many frustrated prospectors decided to leave. Some stayed, but they had to make important changes. The new miners had to dig much deeper than the prospectors. They needed to borrow huge sums of money to buy expensive digging and refining and transportation equipment. The miners soon needed railroads to move gold ore, and smelters to separate gold from other minerals that had less value. Eventually, companies supplanted individual miners. Subsequent silver mining booms followed this pattern as well.

As miners and owners created cities near the mines, often high up in the Rocky Mountains, new challenges arose. Native Americans were displaced, often as a result of violent pressure and treaty negotiations. Trees were quickly stripped from the nearby hillsides and demands for supplies and food drove prices higher and higher. Mines several hundred feet deep posed greater dangers to life and limb than surface prospecting. Smelters featured furnaces that heated gold or silver ore as high as 800 degrees Fahrenheit. Individual miners and collectives could not compete with corporate-run industrial mining. Coloradans had to adapt in new ways to these changes.

Eventually four major mining districts emerged in the state: Central City, Leadville, the San Juans, and Cripple Creek. In this roughly sixty-year time period gold and silver mining generated more than $1.1 billion in revenue.[1] Not all of that wealth stayed in Colorado, as eastern and even European investors sought to profit from Colorado resources. This tremendous mining wealth did help create early millionaires in the state, such as Horace Tabor and Nathaniel Hill. Given the wealth accruing to a privileged few, mine workers at times contested their working conditions and wages in bitter strikes and protests. The industrial system developing around mining would have a profound impact on the state through World War One. After 1930 mining would never again produce such amazing wealth nor employ so many workers in Colorado. Many bustling mining towns became ghost towns leaving crumbling frames and foundations across the mountains of Colorado. But the legacy of mining endures in many ways in the state.

As students will quickly learn from reviewing these sources, mining created most early white settlements in Colorado. Without gold and silver booms, the state would likely have developed more slowly and with far less industry. Ute bands along the western slope and southern Cheyenne and Arapaho could perhaps have remained and coexisted with more gradual white farm settlements along the plains. Instead, desire for the gold and silver deposits in the state created instant cities in Colorado mountains: Central City, Leadville, the San Juan area, and Cripple Creek. Settlement in Colorado did not proceed in a slow, western path along a frontier band from the Kansas border across to Utah. Precious metal and coal mining drew tens of thousands of Euro-American and later Mexican American migrants, along with immigrants from abroad, into the territory and then state. Rapidly swelling mining districts in the mountains in turn drove economic growth and railroad expansion across the state. Mining riches helped to build cities along the foothills such as Boulder, Denver, Colorado Springs, and Pueblo in turn. Colorado government also emerged at the same time as many mining communities. State leaders were regularly called upon to address various mining conflicts and create rules to guide those who built fortunes in these industries. Colorado School of Mines, one of the territory’s first institutions of higher learning, was founded in Golden in 1874.

Industrial mining also altered the Colorado environment dramatically. Mountains sides were stripped of forests; rock debris piled up around mine sites; smelters left behind pools of toxic chemicals and mounds of contaminated gravel. As recently as 2015, the abandoned Gold King Mine in the San Juan mountains leaked waste water containing lead, arsenic, cadmium and other pollutants into the Animas River. The cost of cleaning up mine waste was never factored into the profit/loss balance sheets of nineteenth-century mining and smelter businesses. Those costs are born by Coloradans and the nation today.

***

Sources For Students:

Doc. 1: Colorado State Seal, 1876

Before getting into more specifics, it might help to remember how important mining was to early Colorado settlers. Here is the state’s official seal, created when Colorado became a state in 1876.

This official seal includes some interesting symbols. There are tools on the seal representing only one job though: the pick and hammer of an early miner. The mountains above these tools help situate the location for this job as well.

Questions:

- Why would the founders of Colorado include these images on the seal?

- Why not include symbols from other jobs on the state seal?

- What other kinds of tools do you think miners in the 1800s used?

- “Nil sine Numine” is a Latin phrase meaning: “Nothing is possible without divine help.” Divine refers to God or gods. What might the founders have meant with that phrase? Did it have anything to do with mining?

- If our Colorado government leaders wanted to change this seal, what work or play symbols could they include today? What do you think the most important job or business is in Colorado today?

***

Doc. 2: Michigan Newspaper Report on Pike’s Peak Gold Rush, February 1859

News of gold discoveries in the Rocky Mountain area spread fast after the summer of 1858. By 1859 the Pike’s Pike Gold Rush was on. Here’s how a man who went to Colorado described what he saw.

There is just gold enough to excite a certain class of excitable persons to leave their homes and that is all. There are plenty of speculators laying out towns all through the territory, who sell shares to anyone they can at enormous profits. . . . When you hear persons talking of going to Pike’s Peak just tell them to stay at home, if they can make an honest living.

[Source: Hillsdale Standard (Michigan), February 15, 1859, p. 2]

|

WORD BANK: Excite: motivate, get moving Speculator: a person who guesses what might happen Laying out towns: creating and mapping new streets Shares: stocks in a company Enormous: very large Profits: money made from a sale |

Questions:

- In 1859 why did Pike’s Peak matter to newspaper readers in Michigan?

- What sort of person did the author think would go to Colorado?

- Did the author think that people could get rich in Colorado?

- Did the author think that gold mining was a good way to make a living?

***

Doc. 3: Horace Greeley described Central City, June 1859

As the Colorado Gold Rush began, several New Yorkers went west to see it for themselves. One newspaper owner, Horace Greeley, visited the area that would later become Central City. He wrote details of what he saw. Greeley, Colorado is named after him.

[T]he entire population of the valley—which cannot number less than four thousand including five white women and seven [Indian women]

|

WORD BANK: Entire: all Diggings: place where miners dig for gold Restricted: limited Staples: just the basics Regarded: thought of |

living with white men—sleep in tents . . . cooking and eating in the open air. I doubt that there is as yet a table or chair in these diggings. . . . The food, like that of the plains, is restricted to a few staples—pork, hot bread, beans and coffee. . . . [L]ess than half of the four or five thousand people now in this [valley] have been here a week; he who has been here three weeks is regarded as quite an old settler.

[Source: Horace Greeley, An Overland Journey from New York to San Francisco in the Summer of 1859 (New York: C. M. Saxton, Barker, and Co., 1860), 122, 123]

Questions:

- How did Greeley give us a sense that men especially were rushing into this mountain valley?

- Why didn’t the newcomers stop to build houses and stores and schools?

- What do you imagine would happen to folks in the area when winter starts?

- As an eye witness, Horace Greeley makes good primary source. Why?

***

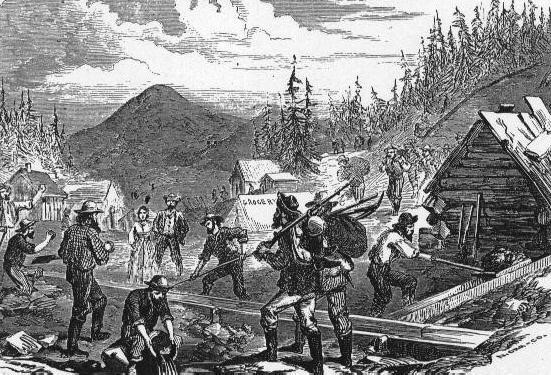

Doc. 4: George White drawing of the area that became Central City, 1867.

Albert Richardson was a newspaperman like Horace Greeley [Doc. 3]. He too published an account of his trip to the Central City area that summer of 1859. Years later Richardson asked New York artist George White to create this picture based on what Richardson remembered from his visit to Colorado.

[Source: George White print made from a wood engraving that appeared in Albert D. Richardson, Beyond the Mississippi (Hartford: American Publishing, 1867).

Questions:

- The wooden slides in the picture were called sluices. How might those help prospectors find gold in streams or waterways?

- This image shows a scene similar to that Greeley wrote about in document 3. What differences do you notice between Greeley’s description and this image?

- There appears to be one woman in the picture. How many men?

- What would a community be like if it were mostly men but only a few women and children?

- This picture was drawn by an artist who didn’t actually visit Colorado. Can we trust that the artist pictured exactly how the gold rush looked? Why or why not?

***

Doc 5: Traveler Bayard Taylor described Central City in 1866

Bayard Taylor visited Colorado about seven years after the gold rush started. In his description below, he focused on different changes to the Rocky Mountains:

[Trees have] been wholly cut away….The great, awkwardly rounded mountains are cut up and down by the lines of paying“lodes,” and are pitted all over by the holes and heaps of rocks made either by prospectors or to secure claims. Nature seems to be suffering from an attack of…smallpox. My experience in California taught me that gold-mining utterly ruins the appearance of a county….[This] hideous slashing, tearing, and turning upside down is the surest indication of mineral wealth.

[Source: Bayard Taylor, Colorado: A Summer Trip (New York: Putnam and Son, 1867), 56.]

|

WORD BANK: Wholly: fully Lode: a collection of metal in the earth Secure claims: make sure that a miner owns a specific spot Smallpox: a nasty sickness like chicken pox that leaves scars behind Hideous: horrible and ugly Indication: sign Mineral: a natural substance in the earth |

Questions:

- Taylor talks about changes to the land or the environment. What examples did you find of these changes?

- Smallpox was a nasty disease that created painful, red sores all over human bodies. Why would Taylor say that the land looked like it had smallpox?

- How did Taylor connect “slashing” and “tearing” to “wealth” or money?

- Was anyone fixing the land (replanting trees, filling holes, cleaning streams) during the Gold Rush? Why or why not?

***

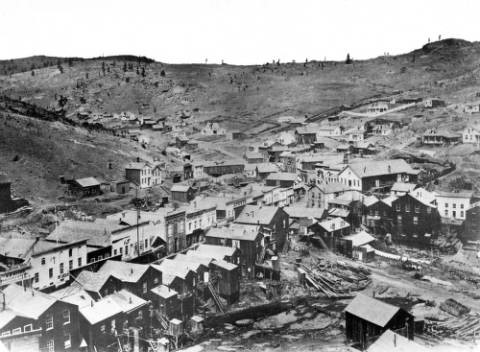

Doc. 6: Photograph of Central City, 1864

The camping scenes described by Greeley and Richardson (Docs. 3 and 4) had disappeared when this photo of Central City was taken in 1864. This was where Clara Brown (in Chapter 2) lived.

[Source: Denver Public Library, “Central City, 1864,” Call # L-609 http://digital.denverlibrary.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15330coll22/id/75009/rec/17]

Questions:

- What kinds of changes do you notice between the drawing in document 4 from 1859 to this photo, taken five years later?

- Before the gold rush, this Central City valley was densely wooded with pine trees, some eighty-feet tall. Where did those trees go?

- Why do all the stores and houses face each other? Why not spread out over the valley?

- If all these building were made of wood, what could happen if a fire started? Remember what happened to Clara Brown? (Hint: check the previous chapter).

***

Doc. 7: Photograph of six miners in Central City, 1889.

By the 1870s, mines were dug deeper and deeper into the Rocky Mountains of Colorado. Prospectors could not pan for gold successfully anymore. Instead, miners worked for large businesses that build mechanical hoists like the one in the picture below. A hoist was a kind of elevator, powered by a coal furnace and steam engine. These men were about to descend for work below. The hoist operator who controlled the miners’ cage is in the background to the left.

[Source: Denver Public Library, “Saratoga Mines, Central City,” Call # X-61094. http://digital.denverlibrary.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15330coll22/id/37944/rec/1

Questions:

- Here six men are going deep underground into tunnels to dig for gold. How is that different from the drawing in document 4? What has changed?

- At the bottom of the picture, you can see small metal rails. What might those be used for?

- The hoist or elevator was powered by coal, but there was not much coal in the ground around this mine. How might mine owners move coal from mines south of Pueblo to Central City?

- These miners were paid about $3 per day to work for 9 or 10 hours underground. They also faced the danger of mine cave-ins or explosions in tunnels. It was very unlikely they would become millionaires. Why would they do this work anyway?

***

Doc. 8: Photograph of the smelting process, 1900

Much of the gold and silver dug out of the mountains in Colorado was stuck inside rock called ore. Miners had to separate the gold and silver from the ore. Basically they would crush the ore, heat it to high temperatures, and add chemicals like mercury to release the gold and silver. This work was done inside stamp mills and smelters. Here is picture of the inside of a smelter used to separate copper from surrounding minerals in rock:

[Source: Denver Public Library, “Converters,” Call # X-60601: http://digital.denverlibrary.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15330coll22/id/35535/rec/155]

Questions:

- The men in the picture are also involved in mining work, though they’re obviously not in an underground tunnel. They are heating metal ore in order to separate copper from the other minerals. Check online to find the melting point (temperature) of copper, silver, and gold.

- What dangers might this kind of work have?

- Railroad cars likely shipped the ore to this smelter. Coal powered steam engines moved those cars. What moves the cart on rails in the picture?

- Smelter workers like these men received about $1.80 to $2.50 per day for ten hours of work in 1900. Why were they paid less than the miners underground, do you think?

***

Doc. 9: Brunot Agreement, 1873

White prospectors discovered gold the San Juan mountain area in southwestern Colorado in the 1860s and early 1870s. Ute Indian bands, however, lived in this area. The U.S. government had earlier made two treaties with Ute leaders that recognized Ute control San Juan Mountains. But pressure from Euro-American miners and settlers led the U.S. government to make new treaties with the Utes in 1873. U.S. agent Felix Brunot made this agreement with Ute leader Chief Ouray. Soon afterward a silver and gold mining boom began in the San Juan Mountains.

- [T]he Ute Nation hereby relinquish to the United States all . . . claim . . . to the following [parts] of the [existing Ute] reservation: [land that later became the Colorado counties of Dolores, La Plata, Hinsdale, Ouray, San Juan, Montezuma, and San Miguel]

WORD BANK:

Hereby: with this agreement

Relinquish: give up or surrender

Permit: allow

Negotiator: someone who helps make a deal between two different sides or groups

- The United States shall permit the Ute Indians to hunt upon [these] lands so long as . . . the Indians are at peace with the white people.

- The United States agrees [to pay] twenty-five thousand dollars [each year] . . . for the benefit of the Ute Indians . . . forever.

- Ouray, head-chief of the Ute Nation, he shall receive a salary of one thousand dollars [per year] for the term of ten years [for his help as negotiator].

[Source: United States Congress, Acts of the Forty-Third Congress—First Session, Chapter 136 (1874). Available online at: http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/vol1/html_files/ses0151.html]

Questions:

- Find the counties from Part One on a Colorado map. Is this a big or small area that the Utes relinquished with this treat?

- What rights did Ute Indians have on these lands, once they were relinquished?

- In Part Three, the U.S. government gave the Ute Indians about $1.25 per acre of land. Did that seem a fair price? How could we find out what $1.25 could buy in 1870?

- Why do you think this treaty did not use the word “sell” or “sale” of land?

- Would other Ute leaders possibly be jealous or resentful of Ouray, since only he received $1,000 per year?

- How might those Ute Indians who disliked this treaty respond to all the new white miners moving into their lands?

***

Doc. 10: Newspaper list of Colorado Millionaires, 1892

Mining in Colorado between 1859 and 1929 created over $1 billion in wealth. By 1892, an Aspen newspaper reported that there were thirty-nine millionaires in Colorado. Many of these men had made their fortunes through mining or by supporting the development of mining in the state. Note that this list does not include those millionaires who later benefited from the Cripple Creek gold boom of the 1890s. The average mine worker earned $3.00 per day in 1892:

There are few who have any idea of the number of millionaires in Denver and in Colorado. One would hardly believe that there are thirty-three . . . in this city. . . . Besides there are six millionaires in the state outside of Denver. . . . [Horace] Tabor heads the list with several millions, all made in mining. Then comes [Nathaniel] Hill, whose money was made in the mining [and smelter] business. . . . David Moffatt accumulated his money in

|

WORD BANK: Accumulate: earned or made Manner: way |

the banking and railroad business. . . . Henry Wolcott has dealt in mines. . . . Dennis Sullivan was a miner. . . . [James] Grant was a miner. . . E. Eildy is another mining and smelting man. Charles Kountze…is in mining. . . . William James accumulated his wealth in the same business. John Reithmann . . . is also in the mining business. Walter Cheesman made his money in mining. . . . Samuel Morgan was a miner. . . . Jerome Chaffee was . . . in the mining business. . . . Outside of Denver, J.J. Hagerman accumulated over a million in mining; [Nicholas] Creede…got his money in the same manner; H.M. Griffin of Georgetown was also a miner.”

[Source: Aspen Evening Chronicle (October 5, 1892)]

Questions:

- How many names on the list of millionaires above made their money in mining? If there were 39 millionaires in Colorado in 1892, what percentage were mining related?

- Can we assume from this list that all miners became millionaires? Why or why not?

- A millionaire mine owner might have hundreds of miners working for him. What kinds of skills did mine owners need to manage that many workers?

- Many of these mine owners chose to live in Denver or Colorado Springs rather than close to the mines. What kinds of houses might they build in those cities? How might mine worker houses look different?

- Some of these millionaires made their fortunes in the San Juan Mountains, where Ute Indians formerly controlled the land. Remember document 9? Why didn’t Ute leaders dig mines and refine gold in that area instead of white miners?

- Have you heard of any names on this list? How are those names connected to buildings or places today?

***

Doc. 11: Modern Map of Historic Gold and Silver Districts in Colorado

In recent years geographers have created maps that tell history stories. Here is a recent map from the Colorado Geological Survey that includes historical and modern information.

[Source: Colorado Geological Survey: http://coloradogeologicalsurvey.org/mineral-resources/historic-mining-districts/]

Questions:

- Look at the different colored areas on this map. The reddish-orange areas were mining districts in the past. In addition to having that common feature, in what other ways are these districts similar?

- The tan counties had gold or silver mining histories. The blue counties did not. How else are the blue counties similar to each other?

- The red lines on the map mark interstate highways like I-70 or I-25 or I-76. Those highways were built in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. Were they somehow used to transport gold or silver in the 1800s? Why might the mapmaker include them here?

- If this modern map included railroads, which did exist in the 1800s, what places would those railroads likely connect?

***

How to Use These Sources:

Option 1: A short lesson could involve first a quick discussion of the state seal. It suggests the importance of mining for Colorado founders. Then students might examine the recent map of gold and silver mining districts (Doc. 11) to get a sense of a basic geographic difference between the mountain counties and those on the plains. Students could also brainstorm what other industries or symbols might have been appropriate for the state seal in 1876.

Then students could begin tracing the developing and impact of mining in the state by comparing Documents 2–4. Documents 2, 3, and 4 provide some detail about the early gold camps, but they don’t always line up neatly together. The newspaper story (Doc. 2) suggests the dangers of gold fever. Document 3 features an eyewitness description of the Central City area. Document 4 was a drawing created years after a visit to Colorado’s gold camps by an artist who did not make the trip. This should raise some questions for students about reliability.

Students could also review the map from Chapter One titled “Route to the Colorado Gold Regions.” This can allow students to get a sense of how prospectors moved into Colorado in an age before paved roads or even railroads. All of these sources can help students describe the early days of the gold rush and the changes in made in Colorado’s Mountains. Students could create an early Colorado map in answer to this question: How might someone who was not a miner draw a map of the state?

Option 2: After completing the initial review of sources 1–4 in Option 1, students might begin to explore the changes from prospecting to industrial mining. Sources 5 and 6 can offer students a chance to consider the environmental changes that mining created in the Central City district. The photograph in Document 6 reveals what historians have called an “instant city.” They could discuss how few city services would exist and how remote this urban outpost was before railroad links arrived in the 1870s. Documents 7 and 8 feature different aspects of industrial mining and highlight how different mining work had become since the early prospecting days.

Option 3: Building on the previous options, students could explore some of the consequences mining had on Native Americans in Colorado as well as the economic changes to the state. Pressure from white settlers in Colorado led to Ute removal after 1879, which enabled miners to move in to the San Juan Mountains. Document 9 includes some key provisions of the Brunot Treaty that the U.S. Government negotiated with Ute Chief Ouray. He was only one of several chiefs, however, and other Ute leaders bitterly resented the loss of Ute lands under the terms of these treaty. They were not fairly consulted by the U.S. government. Even Ouray himself was likely trying to make the best of a bad situation by agreeing to these treaty terms. History Colorado features a collection of documents about the Ute bands in Colorado that could connect with this chapter on Mining.

The newspaper story on millionaires (Doc. 10) can allow students to explore the links between mining and other industrial developments like railroad construction and coal mining. The historical map (Doc. 11) will require some careful study online to find the gold and silver districts and trace their links to Front Range urban centers like Denver or Colorado Springs. Mining did not affect every county in the Colorado, but rather chiefly mountain ones. This mean early population concentrations in remote high altitude communities emerged before most farming towns in the state. Settlement was uneven in the first decades of Colorado history.

- Duane Smith, The Trail of Gold and Silver (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2009) 259. ↵