5

Teacher Introduction:

By the 1860s, many people of European descent had moved into Colorado. Sometimes they moved into lands seasonally occupied by various native groups, including the Arapaho and the Cheyenne. On other occasions, traditional native lands were outright taken over. The increased population also put a strain on natural resources. Tensions were running high by 1864. The Civil War in the East was a battle for the future of America, but so too were the contemporaneous violent encounters on the Plains known as the Indian Wars. One of the goals of the Indian Wars for the U.S. government was to move native people onto reservations. Native people wanted to protect their land use and resist both white settlement and reservations. The Sand Creek Massacre was a part of this series of attacks and battles between whites moving into the West and the native people who already lived there.

The U.S. government policy for dealing with native people had varied over time. Some officials wanted to kill native people; others discussed placing them on restricted lands or reservations. Some white people in Colorado attacked Indians, while others such a trader William Bent acted as intermediaries between native people and the federal government. Several meetings convened by the federal government attempted to address these issues. Frequently, resulting treaties outlined an exchange of native land for goods and annuities provided by the government. The Fort Laramie (1851) and Fort Wise (1861) treaties are examples. Sadly, the government did not consistently meet the terms of these agreements. Colorado and federal officials called for a meeting at Camp Weld near Denver in September 1864, which resulted in the Camp Weld agreement. Some U.S. government officials thought that the problems were now settled. However, several major native leaders did not attend the meeting and did not sign the agreement.

The many bands of Cheyenne and Arapaho also did not have a consistent policy for dealing with white people. Black Kettle led a band of Southern Cheyenne and was a committed peace chief. A band of Southern Arapaho, led by Left Hand (Niwot) was also for peace and sought the protection of the federal government. Other bands, and especially young warriors, wanted to fight for their lands. An order of warriors known as the Dog Soldiers exemplified native people who wanted to fight. Tall Bull was a chief of the Cheyenne Dog Soldiers. Often these warriors were young men and they became the core of resistance to white incursion. In the summer of 1864, members of several of these opposition groups committed raids and degradations that inflamed white anger and panic. Most famously, the Hungate family, who lived about twenty-five miles south of Denver, was discovered murdered in June 1864. Their mutilated bodies were paraded through Denver. The identities of the killers were unknown, but people were quick to blame Cheyenne or Arapaho men. The fall of 1864 was a dangerous time on the Plains.

After the Camp Weld conference, Black Kettle and White Antelope removed their people to Fort Lyon, which became a gathering place for people seeking protection. Major Edward “Ned” Wynkoop commanded Fort Lyon and allowed the group to camp close by. In September, Wynkoop had successfully negotiated the return of four white captives from a Cheyenne camp and led several chiefs to the Camp Weld conference. He did not have orders to execute either of these acts. At Fort Lyon, he acted as though he believed that the people encamped there had been guaranteed safety. He also issued rations to them. Wynkoop was called away in late 1864 and reprimanded for acting beyond his authority. His replacement, Major Scott Anthony, did not feel that he could continue to provide rations and permit trade. He ordered that the encampment move to a place about forty miles away where they could better provide for themselves but still be protected by the troops at Fort Lyon. The Cheyenne under Black Kettle were already there and had been assured by Anthony of their safety. So the camp left for Sand Creek in October 1864.

In Denver, state governor John Evans felt pressure to do something about the situation with native people in the territory. Raiding parties now disrupted mail service and cargo shipments. Evans proclaimed in August that all Colorado citizens could kill “all hostile Indians.” Evans suggested that “friendly” Indians should seek protection, such as near U.S. military posts. Although the Camp Weld meeting would occur in September, for Evans, the time for peace had already passed. He asked for and received permission to raise a regiment for one hundred days of service. These volunteers wanted to prove themselves against the native people and end what they saw only as malicious attacks committed by all native people rather than just a few.

Colonel John M. Chivington commanded the Third Colorado Cavalry. Chivington was already well known for his heroics during the Civil War battle of Glorieta Pass in 1862. The men of the Third did not have the best reputation around Denver and had not seen any action by the time the hundred days was nearly up in November. Chivington and his men departed Fort Lyon for Sand Creek in late November.

In the early morning of November 29, 1864, nearly seven hundred U.S. soldiers attacked the village of roughly eight hundred people at Sand Creek. Many of the men of the village were away hunting. A native leader raised both a U.S. flag and a white flag to signal that his camp was friendly. First cannon shot and gunfire rained down, and then the soldiers tore through the camp. U.S. captain Silas Soule held back his company from the melee but many others attacked with abandon. They slaughtered and mutilated roughly one hundred fifty of the Indians, most of whom were reported to be defenseless.

The massacre of Southern Arapaho and Southern Cheyenne peoples at Sand Creek in 1864 has left a tragic and bitter memory in Colorado and the nation. It was one of the most devastating events in Colorado history and would trigger warfare throughout the Plains. Today, Evans and Chivington are divisive, even notorious figures in Colorado history. Sand Creek remains an important place and site for memorials to many of the tribal groups in the state.

Sand Creek is in southeastern Colorado. The closest modern town is Eads.

***

Sources for Students:

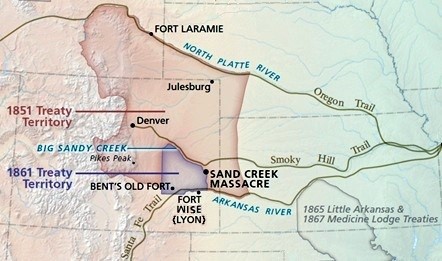

Doc. 1: Map of Fort Laramie Treaty and Fort Wise Treaty

As Euro American pioneers began moving west across lands that became Nebraska, Kansas, Wyoming, and Colorado that ran into different Plains Indian peoples. The two tribes in the corner where Colorado would later meet Nebraska were the Cheyenne and Arapaho nations. These tribes often lived and moved together in pursuit of buffalo (bison). At times, the Indians and white pioneers fought over resources like cattle or horses.

To help avoid these conflicts, the US Army negotiated a treaty with these Indians at Fort Laramie in 1851. On the map below you can see the area reserved under the treaty for the Cheyenne and Arapaho. The army hoped that pioneers could travel freely through this 44 million acre territory but not settle. The Indians hoped they could still hunt buffalo and receive supplies from the US government if they did not bother white migrants.

The Colorado Gold Rush of 1858-1859 changed this situation suddenly. Gold seekers raced to Denver and the mountains to the west in search of this precious metal. In 1859 some 50,000 Euro Americans came into this region and established new towns. Conflicts between whites and Indians increased though many Cheyenne and Arapaho leaders promoted peace between the two groups.

In 1861, the US Army negotiated a new treaty with some Indian leaders from these tribes at Ft. Wise along the Arkansas River. Under this second treaty, the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes were to hunt buffalo in a much smaller area, only 4 million acres, between the two trails noted on the map.

[Source: Eric Sainio, Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site. https://www.nps.gov/sand/index.htm]

Questions:

- How did the land reserved for Indians change from the Treaty of Ft. Laramie in 1851 to the Treaty of Ft. Wise?

- What likely motivated American leaders to change this space available to Indians?

- How might the Cheyenne and Arapaho people have responded to the Treaty of Ft. Wise?

- Do you think the Ft. Wise treaty would tend to promote peace or increase tensions between whites and Indians? Why or why not?

- The Oregon Trail was a popular route for white settlers heading toward the Pacific Ocean in the 1840s and 1850s. How might the Colorado Gold Rush change the movement of whites in this area?

- Compare this map with map 5 in Chapter One. What do you notice?

***

Doc. 2: William Bent Report, 1859

Pioneer William Bent (in Chapter One) described life for the southern Arapaho and Cheyenne people at the time of the gold rush. Bent was white, but had married Owl Woman, a Southern Cheyenne woman. Native people in southern Colorado respected him. He also worked at that time for the U.S. government as an Indian agent. An Indian agent spoke for the U.S. government.

|

WORD BANK: Pressed upon: pushed in Compressed: squeezed Desperate: nearly hopeless Imminent: very soon Inevitable: can’t be avoided Prompt: right away |

“[The southern Arapahos and Cheyennes], pressed upon all around by the Texans, by the settlers of the gold region, by the advancing people of Kansas, and from the Platte, are already compressed into a small circle of territory. A desperate war of starvation and extinction is therefore imminent and inevitable, unless prompt measures shall prevent [it].”

[Source: William Bent in, Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for 1859, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1860), 130]

Questions:

- According to William Bent, what conditions did native people face in 1859?

- What brought those changes to Indian life?

- Does Bent seem concerned for native people?

- These tribes depended on buffalo hunting. How might that change, given the new migrations that Bent described?

- Why didn’t Indians join in the Gold Rush and try to get rich?

***

Doc. 3: Rocky Mountain News Report, 1860

On June 27, 1860 the Rocky Mountain News, a Denver newspaper, reported:

|

WORD BANK: Petty: minor, no big deal War Party: group attacking or raiding Driving: forcing an animal to move Compel: force Eluded: escape from Skirmishing: minor fighting |

“Daily we hear of petty [attacks] by the Indians. . . . A little over a week ago . . . [an Indian] war party on return from fighting Utes robbed several houses in Plum Creek settlement. . . . On Thursday evening a man was driving a cow from the Hermitage ranch into [Denver when] he was surrounded by a party of Indians who tried to compel him to give up the cow. . . . Being on a pony he easily eluded them. . . . [After] a little skirmishing the man escaped with his cow.

Questions:

- How might white settlers respond to this story?

- Were different groups of Indians living in this area?

- Does it seem like many people lived at Plum Creek?

- How could stealing a cow help the Indians and hurt the man with the cow?

- Why wouldn’t the Indians just leave the cow alone and go hunt buffalo?

***

Document 4: Arapaho chief Little Raven and Rocky Mountain News editor, 1861

About a year after the previous newspaper report, the Rocky Mountain News editor described a visit to his office by Arapaho Indian chiefs Little Raven and Left Hand. (There is a picture of Arapaho Chief Little Raven in Chapter Two. He is sitting with William Bent.) The editor wrote that chief Little Raven told him:

|

WORD BANK: Impoverished: made poor Game: animals hunted for food Scarce: hard to find Compelled: forced |

“The settlement of this region by the whites had . . . impoverished the Indians—their game had become scarce, and they were compelled at times to ask for food from the whites. [Little Raven] remembered the advice and the promises of [the US President], and he expected his people would one day receive pay for the land now occupied by whites. He knew that the whites were taking large sums of gold from the mountains.”

[Source: Rocky Mountain News, April 30, 1861]

Questions:

- In what ways did white settlement changed life for Arapaho people?

- What did Little Raven hope the US government would do?

- What were some ways that Little Raven thought about about white people? Do you think the newspaper editor was white?

- Compare this interview with the previous Rocky Mountain News report. How does each one show a different point?

***

Doc. 5: US Army Report, Summer 1864

By the summer of 1864, several U.S. army leaders in Colorado and Kansas began to worry about an open war between white settlers and Indians. In this letter, U.S. Army Major T.I. McKenney wrote his commanding officer in Kansas about the situation in Colorado:

|

WORD BANK: Caution: care Exercised: used Conciliate: make peace with Scouting: Looking for Parties: groups But: Only a |

“In regard to these Indian difficulties, I think if great caution is not exercised on our part, there will be a bloody war. It should be our policy to try and conciliate [the Indians], guard our mails and trains to prevent theft, and stop these [white] scouting parties that are roaming over the country who do not know one tribe from another, and who will kill anything in the shape of an Indian. It will require but few murders on the part of our troops to unite all these warlike tribes of the plains, who have been at peace for years and intermarried amongst one another.”

[Source: T.I. McKenney Report to Maj. C. S. Charlot, (June 15, 1864) in War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I, Volume XXXIV, Part IV, Correspondence (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office)]

Questions:

- This US army officer suggests that soldiers should be cautious and careful. Why?

- He refers to “scouting parties that are roaming over the country.” Who might be in those scouting parties?

- How might scouting parties end up starting a war between Indians and whites?

- Does McKenney think that the army could help keep peace? How?

***

Document. 6: Colorado Governor John Evans Announcement (August, 1864)

By the summer of 1864, Colorado’s governor John Evans gave up on efforts to make peace between whites and Indians. He made this proclamation or official announcement in August:

|

WORD BANK: Parties: groups Pursuit: hunting for Scrupulously: carefully Rendezvous: meet Point: place Indicate: show |

“[M]ost of the Indian tribes of the plains are at war and hostile to whites. . . . Now . . . I, John Evans, governor of Colorado Territory, [give permission to] all citizens of Colorado, either individually or in such parties as they may organize, to go in pursuit of all hostile Indians on the plains, scrupulously avoiding those who have responded to my call to rendezvous at the points indicated; also to kill and destroy as enemies of the country . . . all such hostile Indians.”

[Source: Governor John Evans Proclamation in Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for the year 1864 (Washington, DC, 1965), 230–31.]

Questions:

- What did the governor allow whites to do to “hostile Indians”?

- Why might the leader of Colorado say this?

- In this statement, Gov. Evans seems to disagree with the previous army officer, Major McKenney. How do they disagree?

- How might white settlers feel after reading this invitation by the Colorado governor? How might native people feel?

- What chances for peace between whites and Indians were left after this?

***

Doc. 7: John Chivington’s view of what happened at Sand Creek on November 29, 1864

Governor John Evans told John Chivington to organize and lead a group of volunteer soldiers from among the white settlers of Colorado. These formed the Third Calvary. These men were not trained soldiers of the U.S. Army, but volunteers. On November 29, 1864 Col. Chivington ordered an attack on Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians camped along Sand Creek in southeast Colorado. He had earlier commanded a victorious group of Union soldiers at the Battle of Glorieta Pass in the Civil War.

Five months after the events at Sand Creek, a US government committee asked Chivington about what happened at Sand Creek. You’ll see below two questions posed to Chivington and then his responses.

4th question: [Tell]…the number of Indians that were in the village or camp at the time the attack was made; how many of them were warriors; how many of them were old men, how many of them were women, and how many of them were children?

Chivington’s Answer: From the best and most reliable information I could obtain, there were in the Indian camp, at the time of the attack, about eleven (11) or twelve (12) hundred Indians: of these about seven hundred were warriors, and the remainder were women and children. I am not aware that there were any old men among them. There was an unusual number of males among them, for the reason that the war chiefs of both nations were assembled there evidently for some special purpose.

|

WORD BANK: Obtain: get Remainder: rest Assembled: grouped together |

7th question: What number of Indians were killed; and what number of the killed were women, and what number were children?

Chivington’s Answer: From the best information I could obtain, I judge there were five hundred or six hundred Indians killed; I cannot state positively the number killed, nor can I state positively the number of women and children killed. Officers who passed over the field, by my orders, after the battle, for the purpose of [finding out] the number of Indians killed, report that they saw but few women or children dead, no more than would certainly fall in an attack upon a camp in which they were. I myself passed over some portions of the field after the fight, and I saw but one woman who had been killed, and one who had hanged herself; I saw no dead children. From all I could learn, I arrived at the conclusion that but few women or children had been slain. I am of the opinion that when the attack was made on the Indian camp the greater number of squaws and children made their escape, while the warriors remained to fight my troops.

[Source: Chivington’s Deposition in Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, Massacre of Cheyenne Indians, 38th Congress, 2nd Session (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1865), 101–8]

|

WORD BANK: Passed over: road by horseback over Fall: falling down because of injury Portions: parts Conclusion: decision Slain: killed Squaws: Indian women (not a friendly word to use) |

Questions:

- According to Chivington, how many Indians warriors were in this camp along Sand Creek?

- How many women and children were in the Indian camp?

- Chivington is asked about how many different Indians were killed in the attack. How many warriors did he say were killed by Colorado soldiers? How many women and children did he say were killed?

- If we could ask Chivington how dangerous he thought Indians were in 1864, would he sound more like Major McKenney (Doc. 5) or Gov. Evans (Doc. 6)?

***

Doc. 8: John M. Smith’s Testimony (March 14, 1865)

John Smith was a white government agent who was sent to Sand Creek to check out the Cheyenne Indian camp along Sand Creek before the attack. He was present during the attack and had married an Indian woman. He had previously acted as an interpreter and Indian agent. Like Chivington, Smith was also asked afterward about what happened on November 29, 1864. Below are the questions he was asked followed by Smith’s answers. This is a conversation written down for us to read.

Question: How many Indians were there there?

Smith’s Answer: There were 100 families of Cheyennes, and some six or eight lodges of Arapahoes.

Question: How many persons in all, should you say?

Smith’s Answer: About 500 we estimate them at five to a lodge.

Question: 500 men, women and children?

Smith’s Answer: Yes, sir.

Question: Do you know the reason for that attack on the Indians? Do you know whether or not Colonel Chivington knew the friendly character of these Indians before he made the attack on them?

Smith’s Answer: It is my opinion that he did.

Question: Were the women and children slaughtered indiscriminately, or only so far as they were with warriors?

|

WORD BANK: Character: a person’s way of thinking and acting Slaughter: kill violently Indiscriminately: randomly the balance: the rest Parties: groups |

Smith’s Answer: Indiscriminately.

Question: Can you state how many Indians were killed – how many women and how many children?

Smith’s Answer: Perhaps one-half were men, and the balance were women and children. I do not think that I saw more than 70 lying dead then, as far as I went. But I saw parties of men scattered in every direction, pursuing little bands of Indians.

Question: What time of day or night was this attack made?

Smith’s Answer: The attack commenced about sunrise, and lasted until between 10 and 11 o’clock.

Question: How large a body of [army] troops?

Smith’s Answer: From about 800 to 1,000 men.

Question: What amount of resistance did the Indian [warriors] make?

Smith’s Answer. I think that probably there may have been about 60 or 70 warriors who were armed and stood their ground and fought. Those that were unarmed got out of the way as they best could.

[Source: Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, Massacre of Cheyenne Indians, 38th Congress, 2nd Session (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1865) 6-9]

|

WORD BANK: Commence: started Resistance: fighting back |

Questions:

- How many men, women and children did Smith find camped along Sand Creek? Did he have a different number than Chivington?

- How many Indian warriors fought back? Against how many white army soldiers?

- The word “indiscriminately” means at random. Why is that word important in these questions and answers.

- Chivington insisted that he and his men fought a battle against Indian men. Does Smith describe a fair battle or something else?

- Why might Smith and Chivington have different versions of the events on November 29, 1864?

- How can we fit these two versions together? Should we believe one version more than another? Why?

***

How to Use These Sources:

Why did the Sand Creek massacre happen? The documents here will help students reconstruct events that led up to the attack on November 29, 1864. Soon afterward, there was even a debate about just what had occurred at Sand Creek. The last two sources can help students see the contours of that debate.

Option 1: The first lesson option would be to focus on documents 1, 7, and 8. The first document offers a map of the area and a chance to consider southern Arapaho and southern Cheyenne lands between 1850 and 1864. Students can compare the differences between the treaties on the map. They then answer the questions about the change in boundaries for this Indian territory.

Then students could work in groups to study either the Chivington or the Smith deposition. They could first identify “what” happened, according to their source. This would include how many Indians were present at Sand Creek; how many men; how many women and children; how many of each group were killed. The Chivington source depicts Sand Creek as a battle between hostile men—the Colorado 3rd volunteers and the warriors of the two tribes. The Smith source suggests that a massacre of mainly women and children occurred. After working in groups on individual sources, the class might compare the two to identify the key differences. Students should be able to identify the two different perspectives. Students should notice which areas of the descriptions agree. Even though documents have different perspectives, the facts they agree on can be seen as being more trustworthy than those that differ. You might ask students why the accounts are so different. Neither account voices the native perspective.

After this work, students could still begin to answer the question: “Why did this happen?” Answers would likely depend on whether students were relying on Chivington or Smith.

Option 2: More advanced readers could consider all the documents in turn and then compare them. The first document offers some important background. The map illustrates the change in Indian territory from the Treaty of Ft. Laramie in 1851 to the Treaty of Ft. Wise in 1861. These are key years for the migration of Euro Americans into Colorado.

Then students might then consider documents Two through Six in order to develop a rough timeline of increasing suspicion and hostilities. Some whites and some Indians sought or thought about peace. Others reported only on violence and seemed to stoke fear. These sources could be grouped by students into those two categories: “War is unavoidable” or “Peace is Possible.”

Last, student could turn to the Chivington and Smith sources again. Students should be able to identify the two different perspectives. Students should notice which areas of the descriptions agree. These two sources also align with either the “war was inevitable” perspective or the “peace is possible” view from the earlier sources.

After this work, students could still begin to answer the question: “Why did this event happen?”

Option 3: Have student start this project by reading a Colorado history textbook account of Sand Creek. Then compare that account with the information in these sources. What source information above did the textbook include? What information above was not included in the textbook? How might a textbook version of Sand Creek collect these different perspectives? Advanced students could even try to rewrite the textbook, based on these source accounts.