4

Teacher Introduction:

Like other western states, Colorado offered a home to ranchers who raised their cattle and sheep on the grassy, flat plains and valleys. With the cows and sheep came the cowboys and shepherds who played an important part in the state’s history and the economic success of this business. From the time the Spanish introduced cattle and sheep in North America in the 1500s, the cowboy’s skills and equipment for handling these animals have a long history in the American West. Today, Colorado has become a capital for the ranching industry. Many communities all over the state have operated ranches, and Denver hosts the National Western Stock Show. This event provides an opportunity for modern cowboys to demonstrate these skills in rodeos and other popular events.

Yet cowboys have also become popular in Colorado and American history for reasons that aren’t always easy to understand. The daily work of a cowboy could be boring, lonely, and intermittently dangerous. A stampede of hundreds of cattle could endanger both man and beasts. The weather was scorching in the summer and bitterly cold in the winter. Cowboys moving herds often slept outside, sometimes without tents, and struggled to find decent food to eat. They received little pay for their hard, physical work. Why then have many Americans fantasized about being cowboys? Why have so many Americans idolized the cowboy as a hero of the Wild West? Why less interest in shepherds? These cultural history questions can engage students as they learn not just about the economics of ranching but the meanings we give to these hero-workers of the American West.

Cowboys were typically young men, roughly 16 to 25 in age. They often did not have much education or skills that would have helped them find other types of work. They came from diverse cultural backgrounds. Many of these young men were Hispanic, African-American, Native American, and white American or European. Sometimes they were veterans of the Civil War who did not want to return home or even have a home to return to. One thing that they all had in common was the challenging experience of being a cowboy.

Cattle trails were an important aspect of the western economy during the heights of the open-range era of cattle ranching. That period lasted from roughly the 1860s to the 1880s. Stockmen first moved into Colorado to feed the burgeoning mining districts. They would use the federal Homestead Act to claim land. Then, ranchers from places such as Texas directed their cattle hands to move animals north either to pasture or to railheads, such as Cheyenne, to get their cattle to markets in the East. These cattle drives are part of the iconic experience and image of the cowboy. After the open range era came to a close, many ranchers continued to operate spreads in Colorado. The sources in this chapter can guide students to explore what qualities made a cowboy and the ranching business successful.

Today, many aspects of ranching and ranch work are part of Colorado culture. Dude ranches cater to tourists who want to try their hands at riding and roping. Great fortunes like those amassed by rancher John Wesley Iliff have contributed to educational and social institutions in the state. Many communities have annual rodeos. Even school mascots have been influenced by Colorado’s ranching history.

Ranching has long been an important economic activity for Colorado residents. And cowboys have always been a key ingredient in the success of ranching. Students might begin to learn about ranching by reading descriptions of the economics of the business or by reviewing maps of the state which highlight areas where ranching flourished. They might also think about what sort of resources would be needed for ranching. The sources below also give students the opportunity to compare text and pictures or to use their math skills to calculate ranching costs and profits.

***

Sources for Students:

Doc. 1: Ralph Moody, Little Britches (1950)

Ralph Moody moved as a boy from New England to a ranch outside Littleton in 1906. His family of seven struggled to earn a living from the land, both farming and doing ranch work. Here he describes his experience with becoming a cowboy at about age 10. He was asked to keep track of dairy cows during the day as they roamed on a nearby farm.

By the end of May, school had pretty well petered out. . . . The day after it closed, Mrs. Corcoran came to see mother about getting me to work

| WORD BANK:

Petered out: slowly finished up Quarter Section: land about the size of a football field Switch: a small whip Spry: active and energetic |

for them. They had about thirty milk cows, and used to take cream to Ft. Logan every day. In the summer they pastured the cows on the quarter section south of us. Because there weren’t any fences, somebody had to herd them to keep them from getting into Mr. Aultland’s and Carl Henry’s grain fields. She said she would pay me twenty-five cents a day and I would only have to work from seven in the morning until six at night. . . . [I] was all excited about being a cowboy. My biggest worry was that I didn’t have a ten-gallon felt hat, instead of a straw one from the grocery store in Ft. Logan.

[The next morning] Mr. Corcoran brought out an old work-harness bridle . . . and put it on the horse. Then he boosted me up and gave me a switch. “Old Ned ain’t too spry, but you give him a cut with that switch and he’ll get a move on.” I wasn’t too happy with Ned but at least he was a horse.

[Source: Ralph Moody, Little Britches, (1950) pgs. 57-62]

Questions:

- What kind of work did Ralph Moody do after school ended?

- Would the work described by Ralph Moody appeal to young people today? Why or why not?

- Moody was about 60 years old when he wrote down his memories about being a cowboy when he was 10. How much time had passed between his experience and writing about? Could his memories have changed over that much time?

- Is this the kind of source that can tell us what a real cowboy did around 1900? Why or why not?

- What is the same or different about being a cowboy according to Ralph Moody than what you expected?

***

Doc. 2: Photograph of a “Round up on the Cimarron,” Colorado (1898)

Here is a colored photograph of a roundup in Colorado just before 1900. It was taken near Cimarron. The roundup was a meeting of cowboys who brought together herds of cattle to be sorted, traded, and/or branded by their owners.

[Source: Library of Congress photograph, “Colorado. Round up on the Cimarron,” 1898. Online link for close-ups: https://www.loc.gov/item/2008678198/]

Questions:

- What parts of the landscape can you see in this picture?

- What things did cowboys have to build for a roundup?

- Based on this picture, what do cattle need to live?

- How many horses do you see? How many cowboys? How would cowboys do the roundup if they did not have horses?

- Does this image help make the life of a cowboy appealing? Why or why not?

***

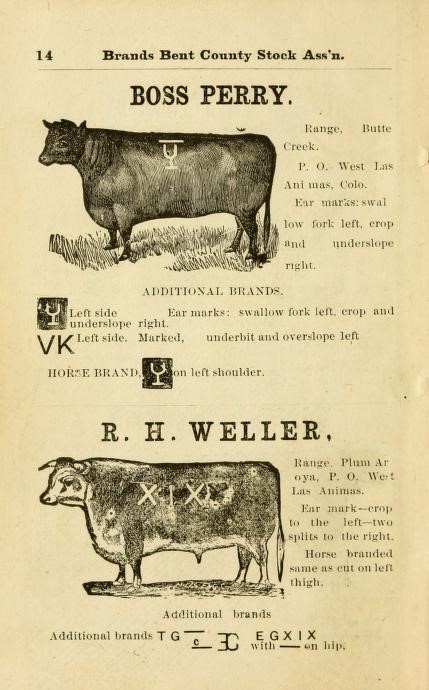

Docs. 3 and 4: Cattle Brands (1885)

Brands are labels on cattle. They let everyone know to whom an animal belonged. Branding was done by burning a symbol into the cow’s hide with a hot iron. This was an important cowboy task. These two documents are from a book that showed what four ranchers’ brand looked like.

|

|

[Source: Brand book, Containing the Brands of the Bent County Cattle and Horse Growers’ Association for the Year of 1885 (Las Animas, Co.: Bent County Cattle and Horse Growers’ Association, 1885)]

Questions:

- Why would ranchers want to brand their cattle?

- Where on the animal might you find the brand?

- Crop means to cut. Where else did cowboys mark cattle?

- What are some of the differences between these cattle?

- What other kinds of animals might people brand?

- What would your brand look like, if you were to design one to mark the stuff you own?

***

Doc. 5: Louis L’Amour on the life of a cowboy (1981)

Louis L’Amour was born in 1908. He worked as a young man with cowboys, miners, and loggers in the West. He became famous for writing many popular Western stories about cowboys and their adventures. Late in his life, he wrote about the real lives of cowboys:

[A cowboy] had to know horses and cattle, and he needed skill with a rope. His average working day during the early years of the range [1860s-1880s] was fourteen hours, from can see to can’t see. . . . His work consisted of rounding up and branding cattle, gathering strays, riding

|

WORD BANK: Bog: A deep muddy area Hardy: tough Breed: A type of animal |

fence, pulling cattle out of bogs, treating cuts…building and repairing fences, cleaning out watering holes, or whatever needed doing. . . .

Stories of the West are said, by those who do not read them, to be about cowboys and Indians. Actually, that is rarely the case. . . . When a cowboy is the [hero] he is usually a drifter and very rarely is shown at work, doing what has to be done on the ranch.

Usually cowboys were between fifteen and twenty-five years of age, although some were as young as twelve or as old as eighty. By and large they were a hardy breed. Their work was hard, brutal, and demanding.

[Source: Louis L’Amour, “The Cowboy: Reflections of a Western Writer,” in Steve Grinstead and Ben Fogelberg, eds., Western Voices: 125 years of Colorado Writing (Golden: Fulcrum Publishing, 2004), 151–52.]

Questions:

- What skills did cowboys need to be successful?

- How old were cowboys?

- According to L’Amour, what kinds of things were cowboys NOT doing in most western stories?

- Does L’Amour make cowboy life or ranch work sound like something you would want to do? Why or why not?

- L’Amour both worked as a cowboy and loved to write fiction stories about cowboys. Does his description of cowboy life sound like fact or fiction?

- Why would L’Amour use the word “breed” to describe a cowboy?

***

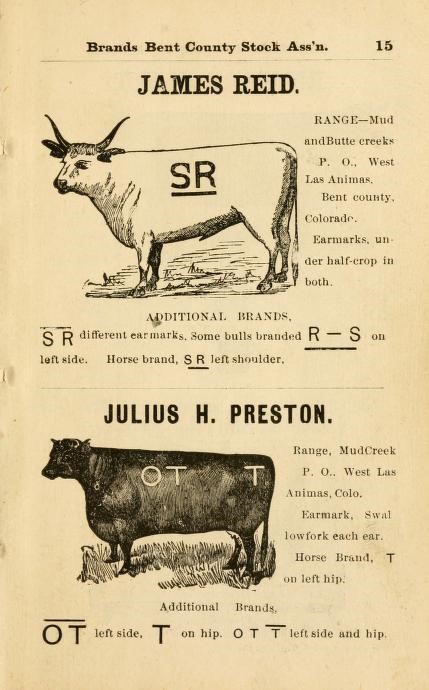

Doc. 6: Photograph of the Second Guard (1905)

Taking care of cattle could be a 24-hour job. Sometimes, cowboys worked in shifts to make sure that the animals were always watched. One group would sleep while another crew stayed alert.

[Source: F. M. Steele, “Second Guard,” Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-36143. http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2016651903/]

Questions:

- What time of day do you think this picture was taken? How can you tell?

- How old do you think the men in the picture are?

- Would cowboy life appeal to the young or the old? Why?

- Can you find anything that all the cowboys have in common?

- What do you think the wagon is for?

- What kind of clothes and equipment did you need to be a cowboy?

- What might these men lack while camping that you might like to have?

***

Doc. 7: John Iliff on ranching (1870)

John Wesley Iliff was an early rancher in northeastern Colorado. He hired many cowboys to manage the thousands of cows that he raised from his ranches near Greeley, Colorado and Cheyenne, Wyoming. Here he wrote in a Denver newspaper about the ranching business:

I have been engaged in the [ranching] business in Colorado and Wyoming for the last eight years [since 1862]. During all that time I have

|

WORD BANK: Engage: participate in Shelter: protect Graze: eat grass Head of: number of |

grazed [cows] in nearly all the valleys of these territories, both summer and winter. The cost of both…is simply the cost of herding, as no feeding or sheltering is required. I consider the summer…grasses of these plains and the valleys as superior to hay…During this time I have owned 20,000 head of cattle.

[Source: Rocky Mountain News (August 3, 1870)]

Questions:

- John Iliff became a very successful rancher in the early days of Colorado history. What key resource did Colorado offer his cows?

- What doesn’t Iliff have to pay for?

- What might “the cost of herding” mean in this passage?

- How were cowboys involved in herding? Iliff doesn’t mention paying cowboys for their work. Where might we look to we find out how much he paid them?

***

Doc. 8: Historian Agnes Spring on the business of ranching

Agnes Spring did research in the 1950s on rancher John Iliff (Doc. 7 above) and found out how much money he made in the ranching business. He raised cows on the grasses in northeastern Colorado and had to pay cowboys to help him manage his cattle:

For a good many years Iliff bought from 10,000 to 15,000 Texas cattle each season. They weighed from 600 to 800 pounds and cost him from $10 to $15 per head [each]. After he had fattened them on grass for a year or two and they had reached 1,000 pounds he sold them from $30 to $37 a head….About forty men were employed on the ranches…during the summer and about a dozen remained for the year around. Wages varied from $25 to $30 per month for [each cowboy].

[Source: Agnes Spring, “John W. Iliff—Cattleman,” in Carl Ubbelhohde, ed., A Colorado Reader, (Boulder: Pruett Press, 1962) 202-203.

Questions:

- This secondary source gives us a chance to do some math about profit. That’s the amount of money a successful business earns. Let’s focus on just one year. Assume that Iliff bought 10,000 cows. If each cow cost $10, how much money did he spend on new cattle?

- Then let’s add the cost of paying his cowboys. That was $25 per month for each cowboy. How much is that for the year? Add that to the cost from question #1.

- Now, let’s figure out how much money Iliff could earn if he sold those 10,000 cows the next year for $30 per head or per cow. How much money is that?

- Last, subtract your answer to question #3 from the answer to question #2. How much money did rancher John Iliff make in an average year?

- The cowboys who did work on his ranch obviously earned much less. What might it take for one of those cowboys to start making money like John Iliff?

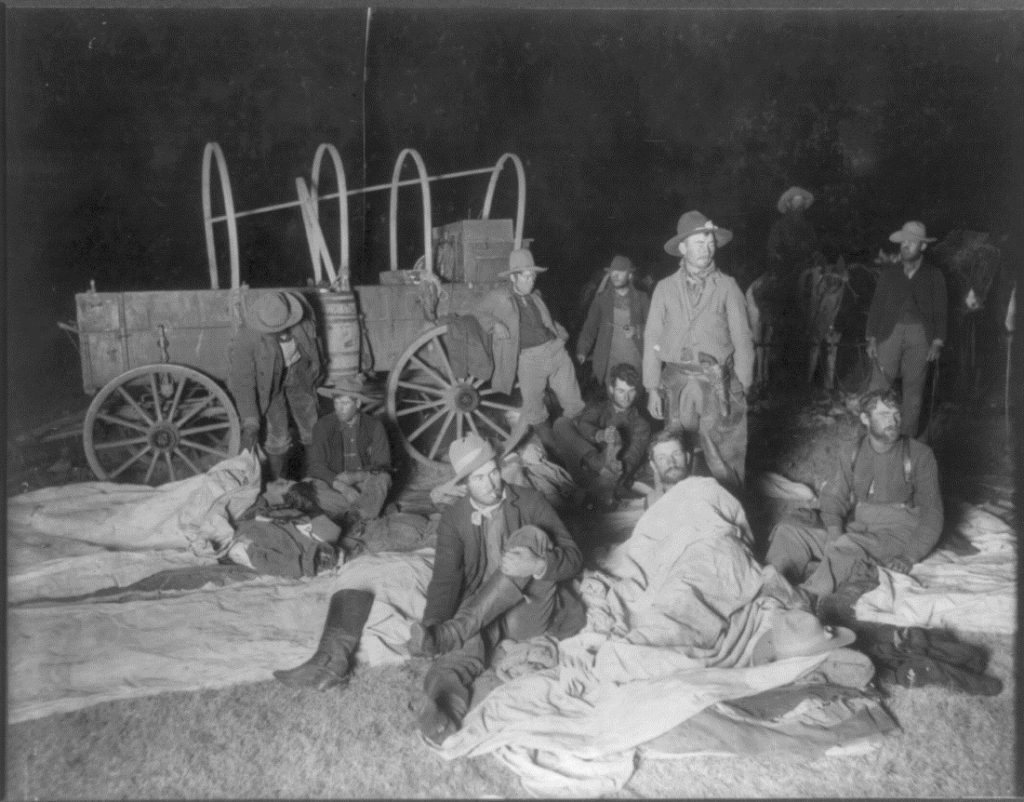

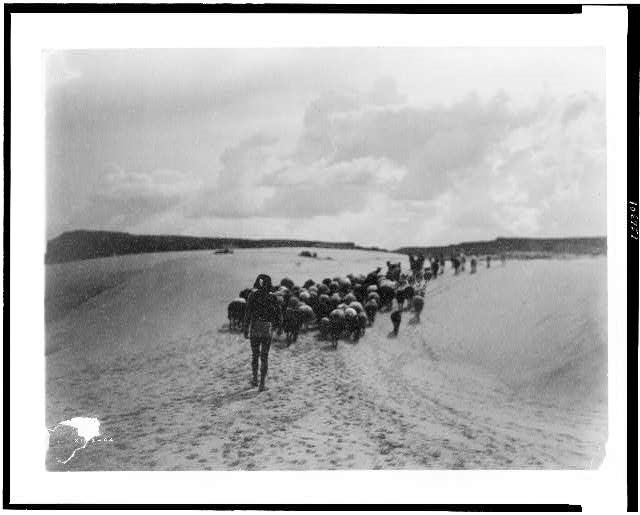

Documents 9, 10, and 11: Shepherds and wool wagons

People who herd sheep are called shepherds. They had some of the same challenges as cowboys. These sheep ranchers were especially important in southern Colorado—the San Luis Valley and on ranches south of the Arkansas River. The photographs below feature sheep and cattle ranchers in the San Luis Valley. Francisco Gallegos of San Luis appears in the first image in front of his family home (behind him and to the right) around 1885. The second photograph shows freight wagons loaded with sacks of wool at Fort Garland, Colorado. The drivers of these wagons were awaiting the arrival of the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad so they could load the wool onto the train. The third photograph shows a Hopi boy who lived in New Mexico. He took care of sheep and horses.

Doc. 9 Francisco Gallegos of San Luis

[Source: Denver Public Library Latinos/Hispanics in Colorado Collection: http://digital.denverlibrary.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15330coll14/id/638/rec/1 scanned from Colorado Society of Hispanic Genealogy, Hispanic Pioneers in Colorado and New Mexico, (Denver, 2006) 14-15]

Doc. 10: Getting the wool to market, around 1900

[Source: Denver Public Library Latinos/Hispanics in Colorado Collection: http://digital.denverlibrary.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15330coll14/id/636/rec/1 scanned from Colorado Society of Hispanic Genealogy, Hispanic Pioneers in Colorado and New Mexico, (Denver, 2006) 208-209]

*

Doc. 11. Hopi boy herding horses and sheep across sand dunes, New Mexico (1905)

[Source: Library of Congress Curtis (Edward S.) Collection, “The end of day, Hopi boy herding horses and sheep across sand dunes, New Mexico,” http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c06759]

Questions for Doc. 9, Doc. 10, and Doc. 11:

- These sheep herders would shear or cut off the sheep’s wool in the spring before summer grazing. What kinds of skills would that require?

- Sheep and cattle both liked to wander as they grazed on grass and other plants. How might a horse help the shepherd or cowboy to gather and corral their animals?

- How might the lives of cowboys and shepherds in southern Colorado be different from those in other parts of the state? You might think about things like the land and the weather. How might different cultures do this work differently?

- The men with the wagons in Document 10 were waiting for a train to arrive. How did could the train help them with their business?

- What would be some challenges to being the boy in document 11? How might his life be the same or different from a cowboy’s life?

***

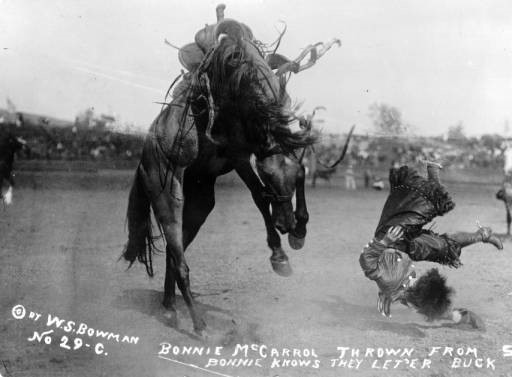

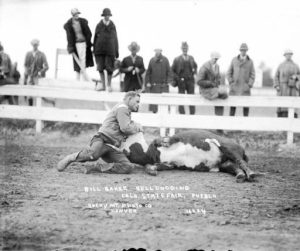

Docs. 12 and 13: Rodeo Skills

The skills that cowboys use at work are also used to compete at rodeos. Rodeo is a Spanish word that describes a roundup. Rodeos became events were cowboys could win prizes for their skills.

Doc. 12: Bonnie McCarrol thrown from Silver (1915)

[Source: Denver Public Library, Photographs-Western History, http://digital.denverlibrary.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15330coll22/id/10771/rec/116]

*

Doc. 13: Bill Baker Bulldogging, Colorado State Fair, Pueblo, around 1920

[Source: Denver Public Library, Photographs-Western History, http://digital.denverlibrary.org/cdm/singleitem/collection/p15330coll22/id/41398/rec/2]

Questions for Doc. 12 and Doc. 13

- What is different about the person in Document 12 than the people in all the other pictures? What does that difference tell you about who was a cowboy?

- What’s happening to Bonnie McCarrol in that photo? What was she doing before the picture was taken?

- How do you think what Bonnie McCarrol is doing is related to being a cowboy?

- Bill Baker is “bulldogging” a steer. What do you think “bulldogging” means?

- What kind of skills do you think each person is demonstrating? Why would they need those skills to be a cowboy?

- Does it look like the cowboys wear different clothes at the rodeo than they would on a ranch?

- Why would people being interested in watching the cowboys? What kind of people do you think they are? Why?

- Does it look dangerous to be in a rodeo?

***

How to Use These Sources:

Setting the Stage: Ask students what they think a cowboy’s life was like in the late 1800s and early 1900s. They might think about ideas such as clothes, food, dangers, and rewards.

OPTION 1: Students might also use computers to look up images of popular cowboy entertainers and actors such as Tom Mix, Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, and John Wayne. They could talk about what might be real or unrealistic about the way these men played cowboys. They could also think about the type of people who are not depicted as cowboys in movies.

Looking at pictures of movie cowboys offers an accessible start to the topic. Students could brainstorm as class the ways that the movie cowboys might be different from a working cowboy with the teacher facilitating the discussion.

OPTION 2: Most of the remaining sources are about a paragraph in length, except for the Ralph Moody excerpt which is much longer. That Moody source might be read aloud by the teacher who could then think aloud for students as she/he reads along. What kinds of cowboy work was Moody doing? Ask students to consider Document 11 too. Moody was about the same age as the boy in document 11. What makes those two boys different? Were they both doing the work of cowboys? Why or why not? These questions could help generate interest in the essential question, tap prior knowledge, and begin a list of key skills or elements that people who work with herd animals must have.

OPTION 3: Then students could review the remaining documents in jigsaw groups.

Group 1: read documents one and six to develop a list of key skills that cowboys needed. This could build on the list already started from the Ralph Moody reading.

Group 2: Documents seven and eight offer a view of ranching as a business. Students working on these two sources could perform the needed math to determine the potential profit in big ranching and contrast that with the money earned by the typical cowboy. These sources help focus students on the economics of ranching.

Group 3: Documents seven, nine, ten, eleven, and twelve often do not show cows. Still, there are figures that are showing the skills of cowboys. Students might return to the original thinking question with these documents in mind. How do these primary sources change their answer to question: what makes a cowboy?

Assessment Idea: After groups have worked through sources and presented their findings to the class, students could return again to the essential question: What makes a cowboy? They might answer that with a presentation or a short written response. Their response might include thoughts about who could be a cowboy. If the Colorado state seal included symbols of cowboy life, what would they be?