8

Eliciting & Interpreting Individual Student's Thinking

Jennifer Ramsdale

By Jennifer Ramsdale, Fleming College

Sometimes we need to find out what our students are thinking. Since reading minds is not a skill available to us, we need to find out in other ways.

Since learning happens entirely within the individual how can we know it is there? I cannot look into the minds of the learners in my classroom and find understanding. Luckily, it is not a question of whether a tree makes a sound when it falls if no one is there to hear it because the learner is there to hear it; they are present for their learning. We need to use techniques that allow them to share what is on their mind so that we can hear it too. Once we know what they are thinking we are much better able to tailor our instruction to their needs.

Strategies and Techniques

The challenge of identifying student thinking is more straight forward than mind reading. It is simply using techniques like language, art or other pieces of work to share what it is in our minds.

- Use questions, prompts, or a task to elicit student thinking.

- The simplest way to do this effectively is to match the learning goals to your questions and activities. For example, “Explain the process of photosynthesis in your own words.” or, “Select a series of home care exercises and perform them in a therapeutic sequence.” or, “How does the artist use shape and color to convey a sense of lightness in this figure?”

- Compare the students’ ideas and work to identify patterns and relationships.

- A comparison can help to highlight patterns and critical ideas as well as increase interaction in your class. For example, “Do you agree with Doug on this point?” or, “How does Daisy’s comment relate to what we studied last week?”

- Use the student’s previous work and thinking to evaluate their progress.

- As you work with your students you will begin to build a picture of their mind, personality, and learning that will help you to tailor your instruction to their individual needs. For example, “Would you be willing to explain how today’s reading has affected your answer?”

- Use a tone of voice and approach that helps you to connect with and support students.

- It is important to minimize the threat of being wrong and take the negativity out of making mistakes by highlighting what is right and how useful mistakes are for the learning process. For example, “You are placing your hands in exactly the right position to do a perfect cartwheel. Using that correct starting position you will be able to straighten your body more fully by increasing your momentum.”

Like choosing a route on a map ask yourself, “What is the easiest path for the learner to get where they need to go?” Simple is better in most cases.

Example – Concept Maps

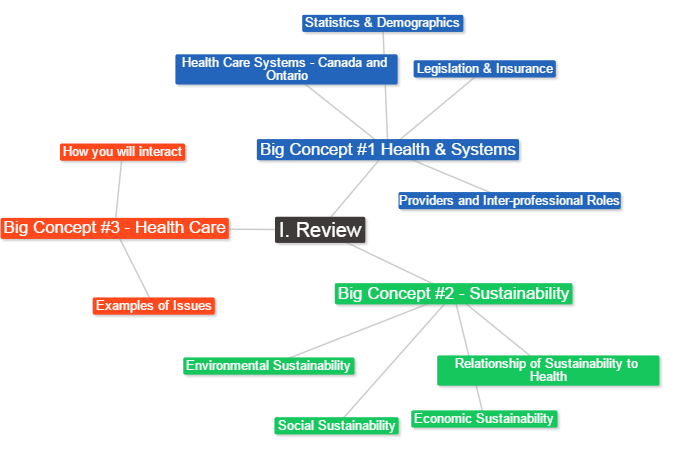

I use concept maps as a teaching tool to make learning more evident. These maps can be used to demonstrate meeting learning outcomes, to make connections between course concepts or between courses, and to connect to life experiences.

Online Concept Map

Creative Process Concept Map

Concept mapping is one of my favourite ways to elicit and interpret student thinking because it can be high tech or low tech, it can be individual or collaborative, and it adds a visual element to make the thinking more explicit. However, concept mapping is only one example of how to making learning more obvious through visual representation.

The teaching skill of eliciting and interpreting student thinking involves an appraisal of what learners know and care about, what they need to learn, the design of questions and tasks, and the observation of what happens. Interpreting student thinking happens anytime you observe students sharing what is in their minds. Then we can adjust our instruction and repeat, no mind reading required.

Author

Jennifer Ramsdale Med, HBA, RMT, Teaching and Learning Specialists for the Learning Design and Support Team at Fleming College. My focus has been on faculty development, curriculum development, and professionalism in teaching and healthcare. I am a practicing Massage Therapist, as well as, an educator in health care professions. I believe that all education is self-education.

Outside of work, you’ll find me in Haliburton where I live with my husband, three children, two dogs and 8 chickens. I continue to learn alongside my family in the pursuit of a great education and connection for all of us. I try to bring my empathy and insight to all my relationships creating more happiness, strength, confidence, flexibility and love in the lives of the people I know.

Resources

- Mary Budd Rowe, “Wait Time: Slowing Down May Be A Way of Speeding Up!”, Journal of Teacher Education, SAGE Publications,1986.

Research on why it is so important to give students time to think when asking questions. Studies have documented that the average teacher’s wait time is less than one second. Pausing at least five seconds (and sometimes more) after both a question and the student response is a great habit to develop. According to research conducted by Columbia University, when teachers waited at least five seconds after asking a question, students lengthened their responses and backed up their claims with evidence.

2. Brandon Cline, “Asking Effective Questions”, https://teaching.uchicago.edu/teaching-guides/asking-effective-questions/ Chicago Centre for Teaching, 2017.

“While asking questions may seem a simple task, it is perhaps the most powerful tool we possess as teachers. If we ask the right question of the right student at the right moment we may inspire new heights of vision and insight.”

Featured image: “Flying Thoughts” flickr photo by Marco Nürnberger https://flickr.com/photos/mnuernberger/25935543665 shared under a Creative Commons (BY) license