Carrie Demmans Epp, Daita Watanabe, Stephen Swann

Introduction

The use of mobile devices for supporting English language learning in Japan started in the 1990s with pocket translators and dictionaries; it has since progressed to the development and study of applications that are dedicated to language learning (Burston, 2014b). In spite of this early work and the commercial availability of a variety of language-learning applications, we have yet to see the widespread adoption of these tools.

Moreover, at least 75 percent of mobile-assisted language learning (MALL) tool evaluations have focused on their use by university students and fewer than 5 percent support the development of more than one knowledge component (e.g., verb conjugation) or language macro-skill (writing, speaking, listening, or reading) (Burston, 2014b). With around eight percent of MALL studies occurring in high-school settings (Burston, 2014b), we lack an understanding of how MALL tools can be effectively integrated into classroom settings which led to this investigation of the use of an adaptive MALL tool within a high school. The selected tool, hereafter called VocabNomad, employs multiple language modalities (textual and audio) to help support student vocabulary knowledge. VocabNomad was integrated into an advanced English course at a private Japanese senior high school. Students were given two types of directed activities: one focused on vocabulary meaning and the other on language production. Students were also encouraged to use VocabNomad in whatever manner met their needs both within and outside the classroom.

This term-long integration of VocabNomad into a high school setting is one of only a few studies that investigates the use of a MALL tool to support classroom activities for an extended period of time (Burston, 2014b). It aims to answer two questions: (RQ1) to what extent can we effectively integrate VocabNomad into an English as a foreign language classroom, and (RQ2) how does VocabNomad use relate to student vocabulary knowledge? Study methods were consistent with design-based research approaches, where qualitative and quantitative data were collected to understand the influence that the integration of a MALL tool had on student learning and the learning environment.

The MALL tool was successfully integrated into the classroom and student learning was observed. However, barriers and instructional norms that hinder MALL adoption were revealed. We discuss these barriers and the opportunities they present. We also provide recommendations that could prevent others from experiencing the challenges we faced or mitigate their impact on the classroom.

Mobile-Assisted Language Learning

MALL tool use is approaching the early-adopter stage within the diffusion of innovation model (Rogers, Sharp, & Preece, 2011). However, MALL lacks the pedagogical acceptance and cultural norms necessary to ensure classroom integration (Burston, 2014a; Kukulska-Hulme, 2013). Learners are not fully prepared to use MALL even if they are interested in doing so (Hsu, 2013; Kukulska-Hulme, 2013; Stockwell & Liu, 2015). This resistance may be partly due to learners not knowing how to best use MALL to support their language learning (Kukulska-Hulme, 2013). Moreover, teachers, who should be able to guide students in MALL tool use, are ill-prepared to provide this guidance.

The repurposing of mobile tools (e.g., podcasts) is not uncommon, but the use of tools, other than dictionaries and translators, that aim to support language learning is rare (Burston, 2014b; Demouy & Kukulska-Hulme, 2010). This may be due to the tendency for these tools to rely on a transmission-based model (Burston, 2014a) or their highly-constrained activities (Kukulska-Hulme, 2013). This focus is unfortunate given that smartphones can support a much wider range of activities that include learner collaboration and noticing (Burston, 2014b, 2014a; Kukulska-Hulme, 2013; Kukulska-Hulme & Bull, 2009).

While there is guidance on how to integrate computer assisted language learning systems, there is a general lack of teacher training or guidance in the selection and use of MALL (Duman, Orhon, & Gedik, 2015; Poole et al., 2011; Son, 2016). This lack of teacher support may be hindering MALL acceptance and use, but it does not eliminate the need for teachers to be able to guide their students in how to effectively use MALL tools (Kukulska-Hulme, 2013; Lai, 2015).

Another factor that may be inhibiting the adoption of MALL in schools, is the lack of evidence for its benefit (Poole et al., 2011), which may be due to the majority of evaluations being design-focused (Burston, 2014b; Duman et al., 2015; Hockly, 2013; Wu et al., 2012), lasting less than half a term (Burston, 2014b), or being conducted in artificial settings (Stockwell, 2010). The evaluation of MALL is also most common at the post-secondary level (Burston, 2014b; Wu et al., 2012) with few investigations including high-school students (Burston, 2014b; Kukulska-Hulme, 2013). This limited evaluation makes it difficult to address teacher and administrator concerns about MALL’s effectiveness.

Many dedicated MALL resemble flash cards (Elmes & Fraser, 2012; von Ahn, 2013) or dictionaries (Tsourounis & Demmans Epp, 2016) with the goal of increasing learner exposure to words. This increase in exposure is often achieved through spaced repetition-based approaches but can be achieved through self-guided study or targeted testing (Demmans Epp, 2017; Elmes & Fraser, 2012). Some MALL tools, such as Duolingo, take a broader approach but even Duolingo has been the target of criticism for its lack of proven effectiveness (Garcia, 2013).

The use of contextual and other information, most commonly a GPS location, to adaptively support student learning is becoming increasingly common (Dearman & Truong, 2012; Son, 2016). This adaptivity usually follows a spaced-repetition model or uses the learner’s location to adjust materials (Burston, 2014a; Dearman & Truong, 2012; Elmes & Fraser, 2012; Stockwell & Liu, 2015). Duolingo and VocabNomad are among those that adjust learning materials by tracking what learners are doing within the system and adapting the learning materials accordingly (Tsourounis & Demmans Epp, 2016; Vesselinov & Grego, 2012). In Duolingo, a placement test is used to determine the types of activities a learner should perform. In VocabNomad, the learners’ behaviours are used to adjust learning materials.

In addition to the above applications, those who are trying to improve their ability to use a language can benefit from the use of mobile support tools that reduce the memory burden associated with a learning activity (Demmans Epp, McEwen, Campigotto, & Moffatt, 2015). PixTalk (De Leo, Gonzales, Battagiri, & Leroy, 2010) is an example of this class of tools that pairs text with a picture illustrating the meaning of a word or phrase. Thus, creating memory linkages between the pictured concept or object and the label that accompanies it, which influences vocabulary acquisition. Regardless of the individual tools’ approach, the effectiveness of these tools and the ease with which they can be integrated into formal learning environments requires additional attention if teachers are to learn how to use them.

Methodology

A design-based project was conducted where 2 teachers (Sensei_1 and Sensei_2) and a researcher (Sensei_3) were given similar levels of control over the tools’ integration into the classroom. This enabled us to explore the use of a new tool without jeopardizing student learning because we could adjust how we were using the MALL tool based on course needs and how students were responding. In this chapter, we focus on the larger picture rather than all of the small changes that were made throughout the course of the project. The adjustments we made are taken into account when considering the implications this work has. We first describe this tool. We then describe the research site, the tool’s integration, and our data collection and analysis procedures.

VocabNomad: an Adaptive Mobile Learning Tool

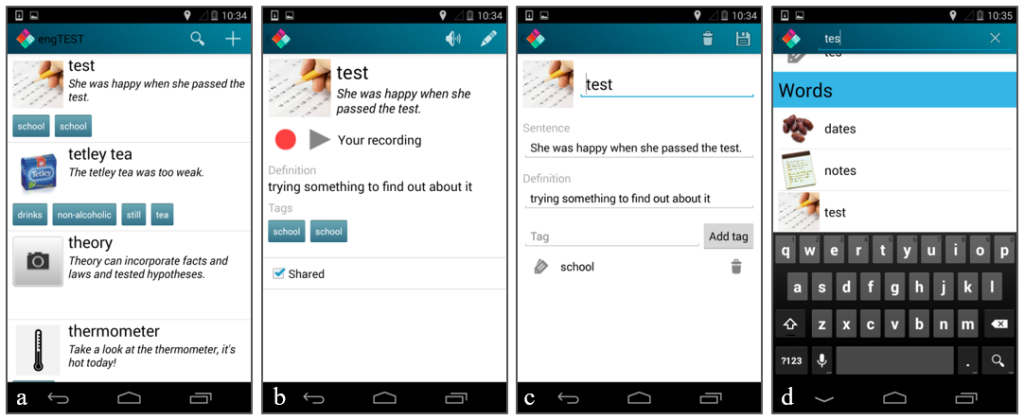

VocabNomad is an application that runs on android smartphones (Tsourounis & Demmans Epp, 2016). It resembles a visual dictionary (Figure 1.a) but goes beyond the normal functions of a dictionary by allowing students to edit entries (Figure 1.c); hear and record pronunciation samples of words or the sentences that demonstrate their use (Figure 1.b); create and share vocabulary entries with fellow learners; request new learning materials (Figure 1.d); and translate words from their mother tongue to English.

The requested learning materials come from a combination of three sources: teachers, other learners, or the application itself. Those that come from the application are generated using processes similar to those employed in search engines (Demmans Epp, Djordjevic, Wu, Moffatt, & Baecker, 2012; Salton & McGill, 1986). The materials created by these processes and other users are transferred to a learner’s device when requested. However, these methods and learner-created materials can be imperfect or impersonal, which is why learners can edit the materials. The combination of editing with learner-created and automatically-generated materials enables the application to provide support to learners based on their emergent interests and needs.

VocabNomad logs everything the learner does. This means every time a learner touches the screen, the item that was touched and when it was touched is recorded. This log information is used to recommend new learning materials, based on established theories of vocabulary learning (Carey, 2010). Please see Demmans Epp (2016b) for a complete technical description of VocabNomad and a discussion of the theories underlying its adaptivity.

Mobile Tool Integration into Class

A user manual (see supplementary materials) and smartphones were distributed during the first class of the term and the tool’s features were demonstrated. Figure 1.2 shows what the students saw when they first entered class. Students were allowed to take the smartphones with them but could only use the laptops when in the classroom. The mobile tool was used to support student activities across the entire term (12 weeks). Vocabulary was distributed to students via VocabNomad and was provided through worksheets (see supplementary materials) that were completed by students.

Learning Activities

Consistent with previous offerings of this course, students were learning how to prepare and deliver presentations using PowerPoint. In the first half of the term, they completed several conversation-based group activities. They also watched and analyzed model presentations. In the second half of the term, students worked in groups to research and prepare a presentation. Each group selected its topic and delivered a presentation at the end of the term.

Two types of vocabulary activities were given to students. One focused on the meaning of vocabulary and the other on its use. During the first half of the term, worksheets were given to students. These worksheets listed thematically relevant vocabulary items and asked students to use the materials that were present in VocabNomad to determine what the equivalent word would be in Japanese. Students could then check their work using a dictionary or translator. In the second half of the term, students were asked to create a list of words that were related to the presentation topic they had chosen. Students also prepared sentences showing how these words could be used. The content students created was curated by Sensei_3 before using VocabNomad to distribute it to the class. Students were expected to use the MALL tool to review the relevant vocabulary prior to each presentation. Throughout the term, students were also encouraged to review vocabulary before class and use VocabNomad or their worksheets to support their classroom activities.

Data Collection

Four types of data were collected: 1) observations of student behaviour, 2) demographic information, 3) self-reported language proficiency, and 4) measures of language knowledge. These varied sources of data were collected because they provide objective and subjective information about student learning, which includes student self-perception. Observational data and demographic data were collected to help explain differences in student language knowledge. Observational data was continually collected and informed adjustments in how the application was being used. Table 1.1 details when data collection was performed for the data that was not based on observation.

Table 1.1

The data collection schedule.

| Study Stage | Demographics | English Proficiency | Vocabulary | Final Exam |

| Beginning | X | X | X | |

| Middle | X | X | ||

| End | X | X | X |

Two types of user observation were performed. The classroom teachers observed student actions to understand students’ usage, and reports from other teachers who saw students using the application or who overheard them talking about it were included since these provided insight into student perceptions and behaviours. The second source of observational data was the automatically-collected logs of student interactions which detail what they did. Samples of student work were also collected to understand their learning.

A demographics form was used to collect information about the students’ mother tongue and exposure to English, the time they had spent in English-language environments, the English-language media they use, and the other learning activities they have or were currently performing. Students were asked to rate their proficiency in English at the beginning, in the middle, and at the end of the term to see if their self-perceptions changed following system use.

Course-specific vocabulary was assessed through a teacher-created final exam. Students were asked to use items from a word bank to complete sentences, to match words to their definitions, to reorganize a collection of phrases and words into a comprehensible sentence, and to read a definition and write the word that was being defined. A standardized measure of receptive vocabulary knowledge (the PPVT-4) was also used (Dunn & Dunn, 2007) to monitor vocabulary learning. The PPVT-4 asks students to identify the image that matches a verbal stimulus from a panel of four images.

Data Analysis

Standard statistical procedures were applied to analyze quantitative data. These procedures are specified when presenting the results for each of these data types. Central tendency (mean and median) and variability statistics are reported to describe the data. The variability statistics include either the standard deviation when the data is normally distributed or the quartile values when the data follows a non-normal distribution.

Student Demographics

The 47 boys, average age 17.5 years (SD = 0.40), who were in the course reported Japanese was both the language they spoke at home and their mother tongue. Fourteen students had one or more parents who spoke English but only 2 had spoken English with a parent: Student37 used English with his parents when travelling and Student16 used English with his father approximately once a week.

Almost all students had been educated in Japan with 3/4 of students having spent less than 2 days in English-language environments. Only 9 students had spent more than 7 days in English-language environments, 4 of whom had spent more than a year abroad. Many students regularly used English media: all listened to English music and 37 occasionally watched television or movies in English. As expected, students whose parents spoke English were exposed to more English (rs = .57, p = .003). This exposure did not include students’ use of English with their parents.

Results and Discussion

Students in this course were in the habit of visiting with their peers using Japanese. They demonstrated hesitance when asked to interact in English, especially if this interaction involved speaking in front the larger group where their peers would have an opportunity to witness errors. In one case, a student said “I don’t speak English” instead of answering Sensei_3’s question in a small group setting.

This hesitance resulted in the introduction of a bonus-mark program where students could earn a few additional marks by responding to teacher questions when activities were performed with the entire class. This change was accompanied by improvements in student willingness to participate in class-level discussions. However, it did not result in the level of improvement that had been hoped for.

Classroom Integration of a Mobile Tool (RQ1)

A technical challenge, where the router could not handle the number of connections, was discovered when we introduced the application. This problem was fixed when a new router was bought.

Students were comfortable using the provided devices as is demonstrated by their personalizing the devices and installing several applications (M = 5.07, SD = 9.62, Max. = 32). Students also used Internet searches and web applications, such as weblio or Google Translate, to find information or translate words, as was evidenced by students (n = 9) returning devices with up to 5 browser tabs left open. Students further demonstrated their integration of the provided mobile device into their practices by logging into their Google (n = 8) and Picassa (n = 4) accounts through the device or by enabling a keyboard (i.e., iWnn_IME) that allows Hiragana input (n = 14). Most students (28) demonstrated confidence by continuing to use English even if they changed the device’s English settings (e.g., setting it to use American English).

Some students only occasionally brought their devices to class while others consistently brought them. Few students used their electronic translators (i.e., small electronic Japanese-English dictionaries) in this class, but students were observed using them in other courses when they were not allowed to use VocabNomad.

Students navigated VocabNomad with relative ease which may be due to the similarity of the icons in VocabNomad with those of other applications (e.g., the save function was represented with an image of a disk).

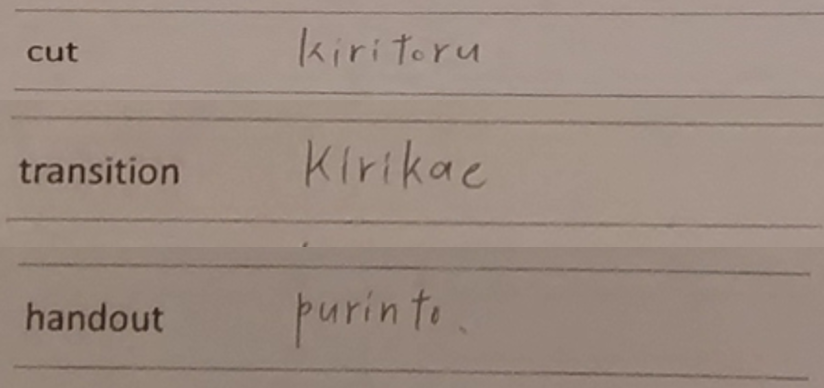

Students used the application in group and individual settings. When working in groups, they used VocabNomad to complete the recommended worksheets. See Figure 3 for examples that come from a worksheet that was meant to scaffold their use of PowerPoint. Figure 3 shows students correctly determined the equivalent Japanese words for cut, transition, and printout.

Students also prepared vocabulary lists to accompany their presentations. Table 1.2 shows some examples of their work. These examples cover a full range of student abilities: those who exhibited low performance levels misused words and exemplary student performance was characterized by the demonstration of more advanced linguistic knowledge (e.g., morphology and appropriate verb conjugations).

Table 1.2

Representative samples of student-generated content.

| Performance Level | Word | Sentence |

| Typical | troubles | He encountered some troubles. |

| Exemplary | inherit | My family thinks that my green eyes are inherited from my grandfather. |

| Low | record | He wasn’t passed as official records. |

If we look at overall system usage (Table 1.3), we can see all students used the system at least some of the time. The Min. row indicates all students used VocabNomad during the first half of the term and those with the lowest usage levels continued to use the application during the second half of the term. Table 1.3 shows some students had high initial usage levels that were not maintained even though these students continued to use the system at a reasonable level. This usage pattern is related to the change in activity type from student worksheets and small group activities to students preparing presentations.

Table 1.3

Number of actions that students performed within VocabNomad (Whole Term) and students’ phase-based usage, by quartile, for all event types.

|

Term Half |

|||

|

1st |

2nd |

Whole Term |

|

| Min |

30 |

0 |

84 |

| Q1 |

869 |

0 |

1,096 |

| Mdn |

1,630 |

45 |

1,648 |

| Q3 |

3,082 |

230 |

3,362 |

| Max |

9,746 |

2,482 |

9,746 |

Table 1.4 allows us to see the types of activities students were performing. It shows students used Japanese and English to find vocabulary within the application. The similar usage of Japanese and English searches indicates individual MALL tools do not need to provide extensive Japanese support given the availability of other applications that can meet this need. This type of multiple tool use was observed during the second half of the term: students initiated the use of Google Translate or weblio to support more open-ended activities, which demonstrates student integration of MALL into their learning practices.

These logs also show students used VocabNomad to study vocabulary (i.e., the Viewing Content row), which is consistent with their assigned learning activities. Students also seemed to enjoy listening to the pronunciation model that VocabNomad provided. They occasionally experimented with these pronunciation models, as is evidenced by both teacher observations and the application logs (see the Listening rows). However, a lack of student awareness for how to turn the pronunciation model off led to embarrassment when a student accidentally triggered its use when a teacher was speaking. Going forward, this is one of the easier challenges to address since basic training or the use of headphones could prevent the problem.

Table 1.4

Selected usage statistics by quartile.

| Feature Use | Min | Q1 | Mdn | Q3 | Max |

| Content Search (Japanese) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 11 | 86 |

| Content Search (English) | 0 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 45 |

| Viewing Content | 0 | 805 | 1,411 | 3,058 | 9,539 |

| Adding Content | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 16 |

| Editing Content | 0 | 0 | 9 | 16 | 22 |

| Sharing Content | 0 | 15 | 24 | 34 | 84 |

| Listening to Content they Created | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 34 |

| Listening to Content | 0 | 4 | 13 | 31 | 154 |

| Requesting New Content | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 17 |

Students were uncomfortable modifying existing content unless they were given permission, which may be why we see minimal content creation and editing activities (see the Editing Content and Adding Vocabulary rows). Student concerns over whether it was acceptable to modify content are illustrated through the actions of Student44, who asked Sensei_3 if it was okay to change one of the sentences. She said yes, and he proceeded to edit the sentence. This event along with a lack of system interactions that relate to modifying content, obtaining new content, or editing content demonstrates that low usage levels do not indicate an inability to use application features. Rather it shows student perceptual barriers to system use. It also shows students need support for integrating these types of technologies into their learning practices. These types of barriers will take more time and effort to overcome and include adjusting the culture of use that centers on teacher-led content creation to one where students feel they are allowed to edit the content they are given through mobile tools. From Table 4, we can also see those who were willing to take the risk of creating content were also willing to share the content they created or modified (see Sharing Content row), suggesting opportunities for socio-collaborative learning through mobile applications.

Students were able to identify appropriate vocabulary to support their classmates (see Table 1.2). This vocabulary was then shared through VocabNomad where students reviewed the provided words. This was the first time this type of learning activity had been performed at this school: it was an important first step towards the socio-collaborative learning approaches that language learners desire (Demmans Epp, 2017).

Language Learning (RQ2)

Both the standardized and classroom-based assessments showed student vocabulary knowledge increased when students were using VocabNomad as did their perceptions of their English abilities. This demonstrates students’ ability to learn English through English in spite of their prior reliance on grammar-translation approaches. The changes in student vocabulary knowledge are detailed before discussing changes in student perceptions of their English-language abilities

Student scores from the vocabulary section of their final exam indicate students learned the content that was distributed through the app: 75 percent of the class received a score of at least 70 percent. The highest score achieved was 100 percent and the lowest score was 30 percent.

A modified administration method (Ramirez, Chen, Geva, & Kiefer, 2009) was used for the PPVT-4, which resulted in the reliable measurement (α = .85) of student vocabulary knowledge. A repeated measures ANOVA was used because PPVT-4 scores (Table 1.5) were normally distributed (p = .31). This test revealed differences in student scores based on time of administration, F(1.712) = 5.314, p = .010, partial η2 = .10; and post-hoc paired t-tests with Bonferroni correction showed student vocabulary knowledge improved during the first half of the term (p = .026), when they were using VocabNomad heavily to complete structured learning activities.

The self-assessment questionnaires were similarly reliable (α = .91) and showed an average improvement of 5.24 percent (SD = 2.12) in students’ self-assessed English-language abilities during the first half of the term, which is when they were using the app heavily. Moreover, this score gain was better (t(46) = 2.01, p = .05) than that measured during the second half of the term (M = – 1.63, SD = 2.24).

Table 1.5

Student’s PPVT-4 scores (%) by administration date

|

Start |

Middle |

End |

||||||||

|

M (SD) |

Min |

Max |

M (SD) |

Min |

Max |

M (SD) |

Min |

Max |

||

|

56.18 (6.57) |

31.59 |

72.37 |

60.53 (7.89) |

12.50 |

92.50 |

57.89 (6.93) |

36.67 |

83.33 |

||

Pedagogical Implications

Japanese learners of English at the secondary-school level are unaccustomed to learning English vocabulary through English. They typically learn the meaning of English words through translation. This means they may need additional opportunities to work with English content for learning to happen. The assigned worksheets seemed to help support this learning and provided learners with a sense of accomplishment since they could see what they had achieved. Another way of motivating MALL tool use would be to give learners a sense of achievement through the mobile application or classroom processes by rewarding effort and encouraging goal setting to better guide their efforts (Tsourounis & Demmans Epp, 2016). In addition to this, Stockwell and Liu’s (2015) finding that participating Japanese students’ preferred accessing materials through computers rather than mobile devices indicates the need to overcome students’ cultures of use. One approach to starting this process would be to highlight the desirable activities of the learners who are willing to take the risk of contributing to system materials. This behaviour was demonstrated by some of the students in this study and could be encouraged from the perspective of the importance of contributing to the group’s development.

The sharing of vocabulary and students choosing to complete the worksheets in groups while using the mobile app shows it can support collaborative learning activities. These group-work and sharing activities were student initiated, which may indicate the challenge of learning English through English supported their socio-collaborative needs. However, the more open-ended activity of creating and giving presentations in English may have needed additional structure to ensure students learned all of the words that were needed to understand their classmates’ presentations.

Like in other studies (Demmans Epp et al., 2015; Demouy, Jones, Kan, Kukulska-Hulme, & Eardley, 2016; Palalas, 2015), students demonstrated excitement and interest in using the application, which was visible by teachers and through the log files. Their usage decreased during the second half of the term, indicating that suggesting review or self-directed activities is not enough to encourage usage even when teacher prompting is performed daily. High school students need to be given concrete tasks that ensure they will perform learning activities. Providing students with worksheets or specific training to guide them through the vocabulary review process could help.

The limited use of certain application features indicates additional training should be provided, even if the purpose of this training is to encourage learners to perform certain types of activities. Students learned while using VocabNomad, they were able to use the system to meet their needs, and at least some of them used all system features. Repeated training and the use of incremental increases in learner autonomy would serve to combat impressions that students are not supposed to edit or create content. Other possible strategies for overcoming this perceptual barrier include dedicating a small amount of time, perhaps 10 minutes once a month, to content editing and creation. Alternatively, students could be tasked with identifying a piece of learning content that could be improved. Students could then improve the content by writing a more meaningful sentence or taking a picture that better illustrates the meaning of the chosen word.

While students were able to use the application features with little guidance, this study confirms teachers need to train students in how to integrate these types of applications into their language-learning processes (Kukulska-Hulme, 2013). Some of the above-suggested strategies could be used to support this process. This support could include an activity where learners share the ways that they have used MALL. Increased teacher familiarity with mobile tools would also help them to better support their students.

The incremental approach we used to integrating VocabNomad allowed students to transition from using the English provided through VocabNomad as a learning resource to creating learning resources outside of the system. The next step would be to have students enter the content once they have received feedback from teachers. Students could also use the application to log the English they encounter in their environment, much like a project that was performed with first-language learners of Chinese (Wong, Chin, Tan, Liu, & Gong, 2010) or the self-initiated logging and real-world use of mobile learning by more advanced learners (Demmans Epp, 2016a, 2017).

Conclusion

The use of a mobile learning application by high school students had a positive effect on their English vocabulary knowledge and self-assessed English-language abilities. Data showed mobile tool use related to student vocabulary knowledge: higher usage levels led to greater improvements in vocabulary knowledge (RQ1). Nevertheless, the design of VocabNomad for use in classroom settings could be improved through the provisioning of additional support.

Advanced foreign language learners used both the mobile tool and the paper-based handouts to support their vocabulary needs during class. Student outcomes may have been different if they had not had access to these handouts which supported learning by increasing their depth of processing. This increased processing was the result of students’ reasoning through the meaning of individual vocabulary items and trying to determine the equivalent Japanese term using the mobile app.

From a pedagogical perspective, the integration of this type of mobile learning is limited by the barriers that result from student perceptions about the use of mobile tools (RQ2). In this context, the barriers that should be overcome centre on the need to develop student autonomy since these learners were accustomed to working under the close direction of an instructor rather than working independently. One way to achieve this goal is to start with prescribed activities and gradually move towards more open-ended activities. The worksheets showed graduation in the amount of work students needed to complete, and the transition to their creating vocabulary lists was the next step. However, more needs to be done in this direction. Teachers and learners should attempt to work collaboratively to determine different ways to improve their use of mobile tools. This use should include mechanisms that provide the learner with a sense of progress or achievement and that encourage learners to continue their independent and autonomous learning efforts. The success of the tool’s integration and its efficacy for supporting learning depends on the teachers and students who are using it. It can only be effective if they are all willing to use the tool to support their learning activities. They must also be equipped to identify barriers and be willing to work towards finding ways to effectively integrate tools in spite of those barriers.