Lucy Norris and Agnes Kukulska-Hulme

Introduction

English could be reframed as ‘a universal basic skill’ and it is increasingly taught from or before the age of 5 together with literacy and numeracy (Dornyei & Ushioda, 2009, p.3). It is also ‘the most commonly taught foreign language all over the world’ (Svartvik & Leech, 2016, p.1) with a ‘special status’ as a border-crossing channel for trans-cultural communication (Svartvik & Leech, 2016, p.1). New technologies and communications “are enabling immense and complex flows of people, signs, sounds (and) images across multiple borders in multiple directions” (Pennycook, 2010, p.593). In this chapter we attempt to harness the ‘strong driving force’ of this impetus for language learning (Kukulska‐Hulme, 2013, p.11) by providing some insights, guidelines and resources to support the design of effective mobile teaching and learning.

Our primary focus in this chapter is the provision of reflective guidance for a mobile and technology supported pedagogy for English language teacher development. However, it is likely that the resources and reflections throughout will be of relevance to teachers of other languages, their educators and more broadly to those working with teachers from a wider variety of subjects interested in mobile learning. Teachers from all sectors are encouraged to develop confidence in their evolving pedagogic and digital practices via the application of 21st Century skills and by becoming familiar with continuing professional development frameworks where design of learning is linked to task and technology (Ertmer, Ottenbreit-Leftwich & Tondeur, 2014; Voogt & Pareja Roblin, 2012). We aim to help those involved in discussions around teaching practices for effective learning with the principled use of mobile devices, and to that end we include examples of good practice and reflections from a variety of K12 (primary and secondary education) teachers.

Extensive research and published literature in the field of Mobile Assisted Language learning (MALL), and more recently Mobile Assisted Language Use (MALU) (Jarvis & Achilleos, 2013) is yet to be fully incorporated into initial training programmes, curricula and professional development frameworks. Baran’s (2014) review of research on mobile learning in teacher education, based on a synthesis of 37 articles, found “an increasing interest in the integration of mobile technologies into teacher education contexts” (p. 22). It is not known how many of these contexts were related to language teaching. Although an increased interest is a positive indication, there is also the issue of how mobile technologies are integrated into teacher education or into learning activities inside and outside of class. Crompton, Burke and Gregory’s (2017) systematic review of the use of mobile learning in PK-12 education revealed that 40% of reported mobile learning activities took a behaviourist approach to learning (e.g. classroom response systems, drill and feedback) which the researchers suggest represents the integration of mobile devices “into existing 20th century teaching and learning practices rather than moving to 21st century learning” (p.61), and it is not helping the learners to become “producers, collaborators, researchers and creators of knowledge” (p.61).

Language teaching is one subject area where this vision could be realized. The pedagogic possibilities implied in a mobile pedagogy for language teaching are rich, for example allowing multimodal communication to be rehearsed and recorded for subsequent analysis, reflection, assessment, correction, and connection with a global network of what might be called ‘expert others’ (e.g. native speakers, more advanced learners of the target language). Learners’ positive attitudes towards mobile constructivist language learning has been noted by Hsu (2013). Other researchers, including Pegrum (2014), have highlighted the development of multiple literacies through the use of mobile devices. This potential for developing contemporary 21st century literacies and pedagogic practices will be missed, however, if teachers, their educators and institutions do not address the constraints involved. These include the darker side of hosting connected digital technologies in schools, with legitimate concerns and a responsibility for protecting the safety, privacy, data and reputations of all those within the community. Other constraints include potential learner confusion or overload caused by the use of mobile applications across several languages and other subjects taught in a school.

By sharing our experiences of designing and implementing language teacher Continuing Professional Development (CPD), we hope to advance and promote the design of communicative, connected, task-based MALL. The chapter begins by reviewing how design for teaching and learning with technology figures in existing frameworks for language teacher Continuing Professional Development (CPD). We report on the outcomes of our Mobile Pedagogy for English Language Teaching project, and draw upon this chapter’s first author’s experience of incorporating the resulting framework into language teacher CPD. The challenges involved in this process inform our subsequent reflections on pedagogical development work with European teachers. These sections culminate in some examples of adaptable tasks for collaborative, collegiate action research and planning, and guidelines for CPD and training. We conclude by suggesting areas and directions for future work and further consideration.

Methodology

To provide some context for the adoption of MALL, we carried out a review to establish the role technology plays in the syllabi of internationally recognised qualifications for teaching English and frameworks for CPD. To this end, we analysed the syllabi of initial training qualifications for those who will be teaching English to adults and TESOL (Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages), in-service and advanced qualifications for more experienced English Language teachers, and Professional Development frameworks aimed at English language teachers. Whilst this was not an exhaustive review, the analysis showed a lack of attention to MALL in well-known language teacher programmes, and also the ways in which this is starting to be addressed in more recent CPD frameworks and online resources.

One proposed pedagogical framework that can be used as part of Professional Development is based on an emerging mobile pedagogy for English language teaching, and it can guide mobile language teaching and learning and support appropriate task designs (Kukulska-Hulme, Norris, & Donohue 2015). This framework was informed by an investigation into the ways in which MALL was being incorporated into current language learning and teaching practices, both formal and informal. The investigation was carried out by the authors and another researcher at The Open University, as part of a British Council research partnership award (2014-15) which supported the Mobile Pedagogy for English Language Teaching (ELT) research project. It included interviews with teachers and learners in the UK (international students and migrants on employment related language courses) to discover their existing MALL practices. The project resulted in pedagogical guidance in relation to adult learners’ use of mobile devices for learning English in different environments, with an emphasis on learning beyond the classroom. The guidance was reviewed by a team of international experts to ensure it was also relevant to a variety of settings.

To complement these research endeavours, we also draw on the first author’s experience of running professional development sessions and workshops for language teachers’ CPD since 2010, and particularly recently within Erasmus + (the European Union programme for education, training, youth and sport), as well as training ‘digital animators’ within the remit of the Italian National Plan for Digital Education. In the time period of April 2016-June 2017 this included sessions or workshops for 40 separate courses consisting of 2-5 days, within longer 1 or 2 week CPD courses for European Union (EU) teachers. Each course had 8-30 participants. Several practical task examples and reflection activities that were used in these workshops and training sessions are included in this chapter.

Design for teaching and learning with technology: frameworks and CPD

It is evident from the integral role that technology plays in teaching aspects of language knowledge and skills that the conception of those knowledge and skills needs to be updated to include the technology-mediated contexts in which language learners communicate and learn. (Chappelle & Sauro, 2017, p.18)

In this section, we provide a brief overview of the role technology plays in the syllabi of some internationally recognised qualifications for teaching English and frameworks for CPD. Initial training qualifications from providers Trinity and Cambridge English Language Assessment (the Certificate in Teaching English to Adults and the Certificate in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages, respectively) do not currently include specific reference to mobile language learning, or associated design of MALL activities. Technology is referred to as relating to planning and teaching skills “including computer & other technology based resources” (Cambridge English, 2017, p. 10), the use of “teaching aids (board, projector, audio-visual equipment, online materials) and ICT (e.g., interactive white board if available)” (Trinity, 2016, p.8). The Cambridge In-Service Certificate in English Language Teaching refers to “appropriate technical aids and media” (Cambridge English, 2015a, p. 10).

In Diploma level curriculum specifications (for more experienced teachers), the terms ‘mobile’ and ‘digital’, and reference to MALL tasks are also noticeably absent. The Trinity Diploma syllabus refers to “audio-visual, computer-assisted language learning and information and communication technology” (Trinity, 2007, p.37). The Cambridge Diploma syllabus refers to “ICT, including electronic resources” and recognises its “impact and potential for language learning” (Cambridge English, 2015, p.4) by requiring candidates to “adapt, develop and create teaching/learning materials/resources, including ICT, for specified teaching and learning contexts” (p. 6).

‘Technology’ in this English language teacher education, it would seem, currently only figures in relation to teacher ‘preparation’ of materials and resources, and critically, no reference to task design is made. In “Designer Learning: The Teacher as Designer of Mobile‐based Classroom Learning Experiences” (2013), Hockly draws on Laurillard’s work (2012) outlining the need for teachers to design effective learning experiences with or without technology. The paradox this conjures (what is mobile in a pre-determined, fixed teaching space?) will be elaborated on in the next section.

Does the place and role of technology play differently in Professional Development frameworks aimed at English language teachers? A number of these exist to give teachers, their managers and their employing institutions a means of mapping skills and competences for “a shared understanding of the key skills, knowledge and behaviours that have been shown to contribute to effective teaching at a variety of levels and in diverse contexts” (British Council, Cambridge English & EAQUALS, 2016, p.1). A joint statement by the authors of the Cambridge English Teaching Framework, the British Council CPD framework, the European Profiling Grid and The EAQUALS Ltd. framework outline their common principles, purpose and use. In the first of these, Cambridge English Teaching Framework, spanning four developmental phases from foundation to expert, technology is described in terms of teaching aids and use of online resources where the term ‘mobile’ appears once, in relation to a device:

(i.e., digital videos, podcasts, learning platforms such as Moodle, downloading tasks onto mobile devices, etc.) (Cambridge English, 2014, p. 4)

The European Profiling Grid describes language teacher competences over six phases of development, in nine languages, and similarly includes a single reference to ‘mobile’. This appears in relation to the most experienced language teacher competence:

…can train students to use any available classroom digital equipment (IWB incl.), their mobiles, tablets etc. profitably for language learning (European Profiling Grid, 2011, p.7)

The term ‘technology’ is absent altogether, while the terms ‘digital skills’ and ‘digital media’ are frequently used and appear as one of the overarching ‘enabling competences’ together with language awareness and intercultural competence.

This is mirrored in the EAQUALS framework (2016), where ‘using digital media’ (p.18) is one of the five key teacher skills and knowledge focus areas. There is reference to ‘standard’ technology for teachers starting out, and specific reference to ‘the various uses of mobile learning devices and applications for language learning’ in their most advanced phase. Skills in relation to the design, planning, selecting, adapting and evaluating of ‘activities, resources and materials’ are described. Unusually, learning beyond the classroom is valued in another key area, ‘resources and materials’: “adapting and using creatively (ICT) to aid learning in and outside the classroom” (2016, p.15).

The British Council’s 2015 CPD framework includes ‘integrating ICT’ as one of the twelve professional practices, with reference to digital content, but not MALL (2015, p. 6). The accompanying website uses the same terminology, (e.g. ‘Setting up activities that support learning by exploiting appropriate digital content, tools and platforms’) and provides a rich variety of multimedia resources to download or stream; teaching tips, research reports, books, guides, lesson packs and webinars. Likewise, the Cambridge English Digital Framework website hosts a suite of online resources, including tests designed to assess digital skills levels across the six categories of the framework; the Digital World, the Digital Classroom, the Digital Teacher, Designing Learning, Delivering Learning and Evaluating Learning (The Digital Teacher, 2017a). On this Cambridge English Digital Framework website there will be an accompanying multimedia set of training and resources developed with teacher feedback identifying what would best help them (in development at the time of writing). The current resources include tips on innovative language teaching practices such as using automated speech recognition in collaborative writing and research tasks. The Cambridge English Digital Framework moves beyond descriptions of teacher competences, and is significantly different in areas of focus, as it is centred entirely on teaching and learning practices involving technology.

Mobile pedagogy for English Language Teaching (ELT): framework and guide

The previous section showed some of the gaps in language teacher programmes in relation to technology and MALL, and the ways in which this is starting to be addressed in more recent CPD frameworks and online resources. Here, we introduce an emerging mobile pedagogy for English language teaching, and discuss a pedagogical framework to guide mobile language teaching and learning (Kukulska-Hulme, Norris, & Donohue 2015). This was informed by insights into the learning potential of a mobile pedagogy, from an investigation into the ways in which MALL was being incorporated into current language learning and teaching practices, both formal and informal.

Our approach is built on the premise that while mobile learning rightly puts a spotlight on learners and their experiences, it sometimes obscures the important role played by teachers when they structure and support those experiences, and when they prepare and equip learners for more autonomous learning (Benson & Voller, 2014). The motivation behind our work was to illuminate what it means for teachers to implement a mobile pedagogy in the classroom and when designing learning activities that may be carried out beyond the classroom. In a world where traditional boundaries between the classroom and the outside world are gradually dissolving, it is vital to consider the implications for language teachers, the design of ‘language lessons’ and the teacher-learner relationship. The four pillars of the Pedagogical Framework developed in the project highlight the teacher’s role (based on their professional wisdom) in relation to three key mobilities: mobile devices, mobile learners and the mobility that is inherent in all living languages and channels of communication. These four elements may be summarised as follows:

TEACHER WISDOM: This highlights the teacher’s personal role and experience in enacting pedagogy. For example, the teacher knows how to foster and create an atmosphere of trust among learners and understands the psychological barriers that may obstruct their willingness to communicate. The teacher understands that personalised and authentic tasks are often more meaningful for students and more motivating. The teacher also understands that learners may achieve different outcomes. Enacting a mobile pedagogy means considering all aspects of pedagogy in relationship with the other three pillars of the framework, namely, device, learner and language.

DEVICE FEATURES: Device features are those that enable multimodal communication, collaboration and language rehearsal, and may be exploited in the course of everyday or professional settings. They are also features that support inquiry and reflection on learning. Learning activity may depend on the ability to connect to the internet in different locations, ideally seamlessly, but bearing in mind aspects such as availability of Wi-Fi or how much it may cost to download a very large file. The time required to download or access resources is another important consideration.

LEARNER MOBILITIES: Mobile learning inside and outside the classroom can help connect real life situations with individual resources and needs, it can encourage active learning and collaboration. Learners may be mobile not only in terms of physical mobility, and so the plural form ‘mobilities’ is useful here. Learner mobilities can include the many places and times when people learn and reflect on learning, the range of contexts and cultural settings they occupy, and the personal goals that motivate learners to keep on learning beyond the confines of the classroom.

LANGUAGE DYNAMICS: Language is not entirely fixed in its forms and functions; it is dynamic, and this is partly due to the rapid evolution of communications technology. New words and expressions emerge and are there to be discovered. A variety of channels and media are available for learning and interpersonal communication, and these may be used to conduct language teaching (e.g. via social media), to practise the target language, and to initiate inquiries about language meanings and language change.

The Pedagogical Framework is meant to support teachers as they think through how their learning activity or lesson designs may take account of these four aspects. In this process, teachers are encouraged to consider how their designs relate to opportunities for learners to engage in inquiry, rehearsal, reflection, and the impact on learning outcomes (for more details on the framework, examples of lessons, resources and further guidance, see Kukulska-Hulme, Norris, & Donohue, 2015).

Pegrum (2014) also highlights the role of mobility in differentiating m-learning from other learning in a fixed location that could take place anywhere, describing a ‘genuinely mobile’ learning experience as one where tasks performed while moving through changing spaces feed into learning, so ‘construction of understanding is situated and embodied’ (2014, p. 143). In his view, a mobile pedagogy depends on teachers and their learners appreciating such knowledge construction, along with collaborative networking, which might ‘require both teacher and learner training in the developing and developed world alike’ (2014, p.109)

This has in fact proved to be the case in workshops with many teachers who have initially found these and other aspects of a Mobile Pedagogy for ELT baffling and unfamiliar ideas. We go on to share reflections and insights gained from working with teachers undertaking CPD training courses in a European context.

Experiences and practices in European CPD

In this section and the next, we draw on the first author’s experience of running professional development sessions and workshops for language teachers’ CPD, particularly within Erasmus +, as well as published research and accounts of practice. Erasmus +, the European Union programme for education, training, youth and sport, states that for a mobility project a school should be aiming to support the professional development of some or all of the school staff, as a part of the school’s European Development Plan and provides funding for training conducted in a member country (Erasmus +, 2017). A 2013 European Schoolnet survey of the use of ICT in education (latest available) revealed a wide variation in the integration of technologies for classroom use:

Only a few use it – and still to a limited extent – to work with students during lessons, and even less frequently to communicate with parents or to adjust the balance of students’ work between school and home in new ways. (European Schoolnet, 2013, p.8)

This appears to be the case for many of the participants on CPD courses reflected on here, but by no means all. Some countries and regions, e.g. Nordic schools, “are ahead of the global curve in the exploration and integration of many emerging technologies” (Becker et al., 2017, p.4).

A collaborative research series exploring the impact of emerging technologies for European Union (EU) schools cites experts agreeing on two imminent trends: ‘the changing role of schoolteachers as a result of ICT influence’ and the impact of social media platforms (Johnson et al., 2014, p.1). Some of the challenges mapped to a framework developed to ‘mainstream’ innovative pedagogical practices include the integration of ICT in teacher education, blending formal with non-formal learning, and involving students as co-designers of learning (Johnson et al., 2014, p.2). Rethinking the role of teachers is an on-going driving force in EU teacher CPD, mandatory for career advancement in some states. It is worth noting that in the vast majority of EU countries, teachers at all levels are civil servants employed by the state, not the teaching institution, and teaching is usually seen as a ‘job for life’. The resulting ambiguity felt by some teachers about the changing requirements of their role is evident in discussions about the need to re-think teaching and learning. Technology use and related teacher anxiety is a key factor in the CPD training courses discussed in this section.

The European Commission publishes a great number of policy and project guidelines, teaching frameworks and reports for schools and their leaders, and although accessible, they are not always visible or known about by teachers. Variations along the lines of ‘I had to come on this course to find out what is going on in my country/the EU’ persist in course feedback. An Italian strategy, the National Plan for Digital Education (PNSD, 2015), was richly funded to bring connectivity and CPD training to increase engagement with digital learning and teaching practices in Italian K12 schools. Designing and teaching on some of the resulting CPD courses for selected Italian ‘digital animators’, who were expected to increase engagement within their schools was a challenging experience, given the lack of familiarity of subject teachers with English (the medium of instruction), and a lack of awareness of and competence in basic technology use, including their own devices. Tellingly, participants on these courses universally described teaching in schools where WiFi was not available for teachers or learners, and a total ban on mobile device use in class by both parties. This exemplifies the gap between the reality of teaching in under-resourced schools and the stated aspirations of policy and strategy initiatives.

Turning now to teacher voice, guiding reflections on teachers’ own learning is crucial in scaffolding the uptake of insights, strategies, and skills developed during the process. Offering such guidance is a steep learning curve for teacher educators, especially in contexts where teachers have never taken part in experiential, collaborative and collegiate learning. This is even more so when the working language of instruction and communication is not shared by those involved. In the context of language training and teaching, perhaps there is a further obstacle, under-reported, but pinpointed by Thornbury & Meddings in 2001, in making a case for abandoning a ‘one-size fits all’ course book teaching model; “language is not a subject – it is a medium” (2001, para.4). When the subject under instruction is the medium in which it is expressed, the decisions about what ‘content’ is get complicated. In the European context there appears to be a lack of opportunity to undergo CPD or training with technology in the mother tongue when compared to its relative availability in English as a Medium of Instruction (EMI). When participants on a course are unfamiliar with the terminology surrounding the technology that is the focus, unaware of the terms/concepts in their mother tongue, and lost in relation to how their own devices work, the learning situation is challenging. In such cases the focus needs to be on the pedagogy, not the technology; furthermore, appropriate technical information and support needs to be available in the mother tongue or other languages as well.

Learning activities for mobile devices “are shaped by how students perceive what tools and resources can or cannot do for them” rather than being determined by the tools and available resources themselves (Song, 2011, p. E164.). In the context of teacher education, this is doubly true; many are unfamiliar with the features of their own mobile devices; The Digital Teacher team at Cambridge English suggest:

There is a danger students may come to view the classroom as the place where they power down, losing access to the real-time knowledge of the wider world they are used to having at their fingertips. (The Digital Teacher, 2017b)

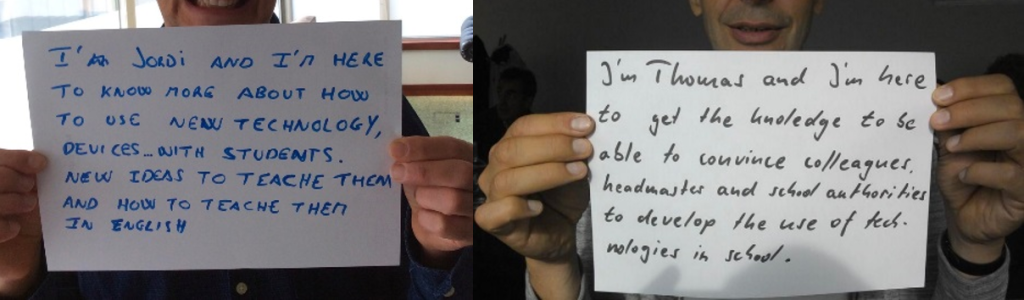

This perceived threat is felt by EU teachers, and the range of reasons for attending a course entitled “Using Technology for Teaching Your Subject(s)” expressed in the examples shown in Figure 4.1 (in the photos and in additional quotes below the photos) is typical.

- “I am here to learn how to convince my school board that technologies – even mobile ones – can improve learning through motivation by ICT use” (Vasco)

- “I am here to learn how to use mobile devices” (Cristina)

- “I’d like to learn how to teach my subjects and help students think critically through technology they use in a limited way…even though at school our tools and connectivity is poor, I’m waiting and operating for better times” (Valeria)

- “I’m here to learn more about technology in the classroom, and CALL” (Dulce)

The ambiguities and anxieties that participants bring to CPD courses, along with a wide range of skills & digital practices calls for a careful selection of familiar teaching practices with digital twists. One such is exemplified in the images in Figure 4.1. Discussing, identifying and sharing priorities is non-threatening when carried out in pairs and small groups. Reporting back via pen and paper (as in Figure 4.1) allows the trainer to present a digital teaching practice that uncovers the way in which mobile devices allow for the capture of ‘analogue’ products of learning (e.g. posters, handwritten or drawn work). A practical activity such as taking photos on their mobile devices as a ‘getting to know you’ task, and posting them on a shared Padlet (or similar online/mobile notice board) exemplifies a mobile learning practice that is immediately transferable to other contexts, both in and out of class. Other ideas are provided in the following section.

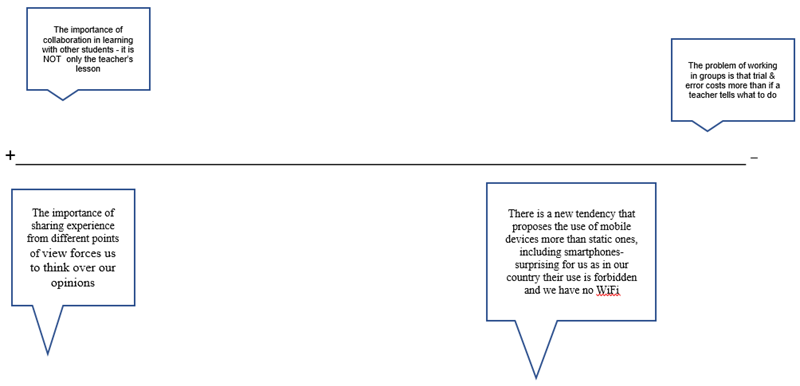

Collaborative learning is often something that teachers have not experienced as learners themselves – very many classrooms in Europe are still laid out in rows, with individual desks, or the occasional horse shoe arrangement. In these classrooms, learners face only the teacher, the focal point and ‘controller’ of information flow, in this ‘one to many’ transmission style of teaching, along with the so-called ‘interactive’ white boards. In reflections answering the question ‘what did you learn about pedagogy today?’ the following quotes show a wide range of reactions to collaborative group exploration of mobile pedagogy in action. Those who are teaching in cultures that do not prize problem solving, inquiry-based group-work, or value the collective sharing of experience in CPD can be lost, and often expect training to take place in a computer laboratory, with lock-step teaching. Figure 4.2 shows some positive and negative reactions to collaborative learning during CPD.

As outlined in the previous section, a mobile pedagogy for ELT (applicable to other subject areas) is founded on the belief that while mobile devices can support self-directed learning and language learner autonomy, the role of teachers is equally important. In the same way that placing learners in groups to work collaboratively is challenging, many teachers flounder when faced with the need to direct, and provide guidance to support self-directed and autonomous learning. Purushotma (2005:80) noted over a decade ago that the guidance given to students learning languages beyond the classroom has changed very little over the past century. Tellingly, perhaps, in the training described in this context, conducted over a 6 year period, participants proved united in their refusal to engage in mobile learning tasks outside CPD sessions, or in preparation for courses. If language teachers on CPD courses taking place in target language countries are themselves unwilling to explore mobile learning practices out of class (essentially viewed as ‘homework’), there may be some uncomfortable questions to be answered by those involved in teacher CPD. Ironically, many of the same participants expressed despair at the way their own learners’ failed to engage in homework, or flipped learning tasks.

We uncovered evidence during our research and in teacher CPD of how digital tools designed to allow collaborative learner input and discussion are frequently co-opted by teachers and used in a more teacher-centred manner. In one example given by a teacher in the Mobile Pedagogy in ELT project (described earlier), a group or pair class quiz app (such as Socrative), designed for learners to post answers on their own and each other’s mobile phones, was used as a presentation tool. Teacher learning journals and observations in the CPD workshops reveal teachers using their own mobile devices to answer questions after a whole class hands up consensus vote, rather than by pairs discussing and moving through the quiz at their own pace, using their own devices. The challenge of mobile-assisted language learning is not simply to transpose “current teaching and learning materials and practices to a mobile device, but a complete reconceptualisation of these” (Kukulska-Hulme, Norris & Donohue, 2015, p.3). As discussed, addressing this provides many challenges to those unfamiliar with the benefits of inquiry-based, reflective, student-centred learning that may connect learning in and out of classroom spaces. One Danish primary school teacher who embraced this approach describes in positive terms her first experiments with handing over to students in this way (see Figure 4.3). The next section goes on to provide guidance in scaffolding such experimentation.

Tasks and guidelines for teacher development

School teachers with many years of experience may prove to be reluctant learners and present particular challenges, weary and jaded from constantly changing education reforms and policies. Language teacher professional development, as opposed to initial teacher training, is often thrust upon unwilling teachers, mostly because they are not involved in decisions about the type and nature of training being provided, and they are obligated to attend. A barely supressed, ‘rolling eyes’ cynicism can rule when teachers with over two decades of successful practice are faced with techno-evangelists with no experience of teaching in their particular context. This type of technology training is like preaching to the unconverted, and often consists of ‘takeaways’ in the form of practical activities for teachers to replicate, with scant attention to pedagogic processes, or teacher wisdom in the room. When time is not spent reflecting on how and why learning is or is not taking place, and the training is not followed up in a collegiate manner, whole school professional development is not sustainable. It is necessary to be clear about the need for all teachers in a department (and whole school) to participate in meaningful, scaffolded conversations, and potentially ‘unlearn’ or rethink current practice.

Before investing time and money, language teachers and their educators need to consider the impetus motivating Professional Development and associated in-service training actions. It is vital to consider all the factors involved for successful impact on subsequent teaching and learning. This would include a review of skills that might need to be developed and assessed. For example, with regard to so-called 21st Century skills (e.g., meta-cognition, critical thinking, creativity, collaboration, media and computing literacies), Ananiadou & Claro found ‘virtually no clear formative or summative assessment policies for these skills’ (2009, p. 4), but they described the ways in which developing teacher ICT pedagogical skills aligns to the promotion of the skills involved. Since then, there have been several publications for teaching and assessing in this area (e.g. National Research Council, 2012; Griffin, McGaw, & Care, 2012; Griffin & Care, 2015).

The ‘C’ in CPD (‘Continuing’) is a misnomer in many teaching contexts, often left to teacher associations or international or local publishers rather than approached in a systematic way. We propose here a list of questions that need to be addressed (and they should be edited, remixed or elaborated on, depending on local context and circumstances):

Download Questions (PDF)

See Digital Extras section for a Slideshow Presentation of the Questions

Practical Activities for Teacher Development Programmes

Two detailed classroom based MALL tasks for language learning, and subsequent reflection, are presented in the Digital Extras that follow this chapter, much of which is transferable to teachers of other subjects, or in contexts where EMI (English as a Medium of Instruction) or CLIL (Content and Language Integrated Learning) is involved. A selection of other practical activities can be found in our teacher guide, Mobile Pedagogy for English Language Teaching (Kukulska-Hulme, Norris, & Donohue, 2015)

See Mobile Pedagogy for English Language Teaching – a guide for teachers

The suggested approach is “loop-input”, i.e. combining the experience of working on tasks as a learner, with subsequent reflection from a teacher perspective. Doing both simultaneously is not advisable. For teachers, working on and in a second language, with unfamiliar digital tools, technologies and pedagogic practices with (possibly) previously “undiscovered” personal mobile devices, is highly demanding. The potential for cognitive overload is high, without very careful consideration of timing and task. Where possible, it would be beneficial for training to be conducted in the mother tongue, or with the aid of one or more bi-lingual technical experts.

Activities suggested in the Digital Extras sections that follow this chapter focus on pedagogy where English is the language under study, as well as on the supporting or assisting mobile technology. In a plurilingual training context, it is important to allow translanguaging, “the ability of multilingual speakers to shuttle between languages, treating the diverse languages that form their repertoire as an integrated system” (Canagarajah, 2011, p.401). For many language teachers, working with emerging mobile communication technologies is like operating in an alien language, in rapidly changing uncharted territories. Reflection is best undertaken in the mother tongue, with slow, silent thinking time to make notes, before using all learning repertoires to share with colleagues.

Discussion and Conclusions

Our focus in this chapter has been the provision of guidance for teachers to support them in their professional development in a mobile and technology supported pedagogy for which they have not previously been prepared. In our brief review of the role technology plays in the syllabi of internationally recognised qualifications for teaching English, we noted that technology in English language teacher education currently only figures in relation to teacher preparation of materials and resources, without reference to task design. In Professional Development frameworks aimed at English language teachers, there is little or no mention of mobile task designs, and mobile technologies are referred to using the umbrella term ‘digital’. This may be a deliberate choice, since the British English term for a cellphone is a ‘mobile’, which encourages a misconception of MALL caused by the conflation of terms – the device being the thing driving or enabling the learning, as opposed to the facets described in our Mobile Pedagogy framework. This umbrella use of the term ‘digital’ is exemplified in Digital Language Learning & Teaching (Carrier, Damerow, & Bailey, 2017). Yet we would argue that there is still merit in retaining the term “mobile” as a way to draw attention to the multiple mobilities involved when using mobile devices in contemporary communication and language learning.

In our research project for The British Council, we were able to develop a pedagogical framework that is centred on mobile language learning, recognising teacher wisdom, mobile device features, the dynamic nature of language and learner mobilities. This framework invites teachers to think about mobile learning opportunities beyond the classroom and suggests a repertoire of learning activities. The use of the framework in teacher development sessions has led to reflections on how mobile learning can be realistically integrated into current practice. The changes implied by the integration of mobile devices into language teaching are wide-ranging and include changes in individual teachers’ beliefs and practices as well as addressing broad questions relating to curricula, infrastructures, professional development and organisational support. The Mobile Pedagogy for ELT framework which we developed has reportedly been used in various settings, for example to help address the challenges of mobile learning for Initial Teacher Education in Portugal (Luís, 2016).

In terms of professional development practice, the Digital Extras sections that follow describe two classroom-based MALL tasks for language learning, and subsequent reflection, to illustrate the experience of teachers working on tasks as learners, and then undertaking reflection from a teacher perspective, using mobile technology. As noted by Crompton, Burke and Gregory (2017), teachers should be helping learners to become producers and creators of knowledge who are adept at research and collaboration. The tasks are illustrative examples of how teachers can learn and reflect together and think about their students’ learning outcomes. Alongside the suggested activities we would advise that trainers should support and encourage CPD participants (i.e. language teachers) to establish a PLN, or Personal Learning Network, to continue discussing and sharing the ways in which lessons and ideas learned in training sessions have impacted on their practice. Networks of this type may thrive on social media platforms such as Twitter (Visser, Evering & Barrett, 2014; Lord & Lomicka, 2014). Another way forward is to consider some “action research” or a joint project among teachers to help develop and evaluate the adoption of mobile learning and make it sustainable.