13

How Do You Define a Community?

Richard E. West & Gregory S. Williams

Editor’s note: The following article was first published under an open license in Educational Technology Research and Development with the following citation:

West, R. E. & Williams, G. (2018). I don’t think that word means what you think it means: A proposed framework for defining learning communities. Educational Technology Research and Development. Available online at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11423-017-9535-0.

A strong learning community “sets the ambience for life-giving and uplifting experiences necessary to advance an individual and a whole society” (Lenning and Ebbers 1999); thus the learning community has been called “a key feature of 21st century schools” (Watkins 2005) and a “powerful educational practice” (Zhao and Kuh 2004). Lichtenstein (2005) documented positive outcomes of student participation in learning communities such as higher retention rates, higher grade point averages, lower risk of academic withdrawal, increased cognitive skills and abilities, and improved ability to adjust to college. Watkins (2005) pointed to a variety of positive outcomes from emphasizing the development of community in schools and classes, including higher student engagement, greater respect for diversity of all students, higher intrinsic motivation, and increased learning in the areas that are most important. In addition, Zhao and Kuh (2004) found learning communities associated with enhanced academic performance; integration of academic and social experiences; gains in multiple areas of skill, competence, and knowledge; and overall satisfaction with the college experience.

Because of the substantial learning advantages that research has found for strong learning communities, teachers, administrators, researchers, and instructional designers must understand how to create learning communities that provide these benefits. Researchers and practitioners have overloaded the literature with accounts, studies, models, and theories about how to effectively design learning communities. However, synthesizing and interpreting this scholarship can be difficult because researchers and practitioners use different terminology and frameworks for conceptualizing the nature of learning communities. Consequently, many become confused about what a learning community is or how to measure it.

In this chapter we address ways learning communities can be operationalized more clearly so research is more effective, based on a thorough review of the literature described in our other article (West & Williams, 2017).

Defining learning communities

Knowing what we mean when we use the word community is important for building understanding about best practices. Shen et al. (2008) concluded, “[H]ow a community of learners forms and how social interaction may foster a sense of community in distance learning is important for building theory about the social nature of online learning” (p. 18). However, there is very little agreement among educational researchers about what the specific definition of a learning community should be. This dilemma is, of course, not unique to the field of education, as rural sociologists have also debated for decades the exact meaning of community as it relates to their work (Clark 1973; Day and Murdoch 1993; Hillery 1955).

In the literature, learning communities can mean a variety of things, which are certainly not limited to face-to-face settings. Some researchers use this term to describe something very narrow and specific, while others use it for broader groups of people interacting in diverse ways, even though they might be dispersed through time and space. Learning communities can be as large as a whole school, or as small as a classroom (Busher 2005) or even a subgroup of learners from a larger cohort who work together with a common goal to provide support and collaboration (Davies et al. 2005). The concept of community emerges as an ambiguous term in many social science fields.

Perhaps the most frustrating aspect of researching learning communities is the overwhelming acceptance of a term that is so unclearly defined. Strike (2004) articulated this dilemma through an analogy: “The idea of community may be like democracy: everyone approves of it, but not everyone means the same thing by it. Beneath the superficial agreement is a vast substratum of disagreement and confusion” (p. 217). When a concept or image is particularly fuzzy, some find it helpful to focus on the edges (boundaries) to identify where “it” begins and where “it” ends, and then work inward to describe the thing more explicitly. We will apply this strategy to learning communities and seek to define a community by its boundaries.

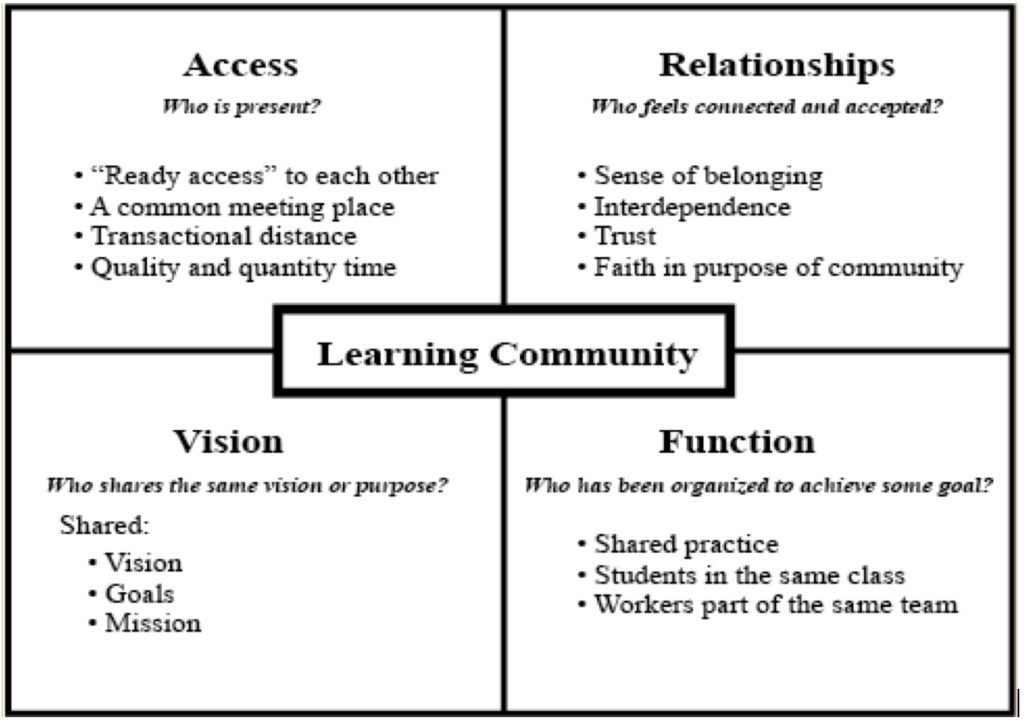

However, researchers have different ideas about what those boundaries are (Glynn 1981; Lenning and Ebbers 1999; McMillan and Chavis 1986; Royal and Rossi 1996) and which boundaries are most critical for defining a learning community. In our review of the literature, we found learning community boundaries often defined in terms of participants’ sense that they share access, relationships, vision, or function (see Fig. 1). Each of these boundaries contributes in various ways to different theoretical understandings of a learning community.

Figure 1. The defining characteristics of learning communities, representing different ways of defining the boundaries of a community

Figure 1. The defining characteristics of learning communities, representing different ways of defining the boundaries of a communityCommunity defined by access

Access might have been at one point the easiest way to define a community. If people lived close together, they were a community. If the children attended the same school or classroom, then they were a school or class community. Some researchers and teachers continue to believe that defining a community is that simple (For example, Kay et al., 2011).

This perception about spatial/geographic communities is common in community psychology research, but also emerges in education when scholars refer to the “classroom community” as simply a synonym for the group of students sitting together. Often this concept is paired with the idea of a cohort, or students entering programs of professional or educational organizations who form a community because they share the same starting time and the same location as their peers.

However, because of modern educational technologies, the meaning of being “present” or having access to one another in a community is blurred, and other researchers are expanding the concept of what it means to be “present” in a community to include virtual rather than physical opportunities for access to other community members.

Rovai et al. (2004) summarized general descriptions of what it means to be a community from many different sources (Glynn 1981; McMillan 1996; Royal and Rossi 1996; Sarason 1974) and concluded that members of a learning community need to have “ready access” to each other (Rovai et al. 2004). He argued that access can be attained without physical presence in the same geographic space. Rovai (2002) previously wrote that learning communities need a common meeting place, but indicated that this could be a common virtual meeting place. At this common place, members of the community can hold both social and intellectual interactions, both of which are important for fostering community development. One reason why many virtual educational environments do not become full learning communities is that although the intellectual activity occurs in the learning management system, the social interactions may occur in different spaces and environments, such as Twitter and Facebook—thus outside of the potential community.

The negotiation among researchers about what it means to be accessible in a learning community, including whether these boundaries of access are virtual or physical, is still ongoing. Many researchers are adjusting traditional concepts of community boundaries as being physical in order to accommodate modern virtual communities. However, many scholars and practitioners still continue to discuss communities as being bounded by geographic locations and spaces, such as community college math classrooms (Weissman et al. 2011), preservice teachers’ professional experiences (Cavanagh and Garvey 2012), and music educator PhD cohorts (Shin 2013). More important is the question of how significant physical or virtual access truly is. Researchers agree that community members should have access to each other, but the amount of access and the nature of presence needed to qualify as a community are still undefined.

Community defined by relationships

Being engaged in a learning community often requires more than being present either physically or virtually. Often researchers define learning communities by their relational or emotional boundaries: the emotional ties that bind and unify members of the community (Blanchard et al. 2011). Frequently a learning community is identified by how close or connected the members feel to each other emotionally and whether they feel they can trust, depend on, share knowledge with, rely on, have fun with, and enjoy high quality relationships with each other (Kensler et al. 2009). In this way, affect is an important aspect of determining a learning community. Often administrators or policymakers attempt to force the formation of a community by having the members associate with each other, but the sense of community is not discernible if the members do not build the necessary relational ties. In virtual communities, students may feel present and feel that others are likewise discernibly involved in the community, but still perceive a lack of emotional trust or connection.

In our review of the literature, we found what seem to be common relational characteristics of learning communities: (1) sense of belonging, (2) interdependence or reliance among the members, (3) trust among members, and (4) faith or trust in the shared purpose of the community.

Belonging

Members of a community need to feel that they belong in the community, which includes feeling like one is similar enough or somehow shares a connection to the others. Sarason (1974) gave an early argument for the psychological needs of a community, which he defined in part as the absence of a feeling of loneliness. Other researchers have agreed that an essential characteristic of learning communities is that students feel “connected” to each other (Baker and Pomerantz 2000) and that a characteristic of ineffective learning communities is that this sense of community is not present (Lichtenstein 2005).

Interdependence

Sarason (1974) believed that belonging to a community could best be described as being part of a “mutually supportive network of relationships upon which one could depend” (p. 1). In other words, the members of the community need each other and feel needed by others within the community; they feel that they belong to a group larger than the individual self. Rovai (2002) added that members often feel that they have duties and obligations towards other members of the community and that they “matter” or are important to each other.

Trust

Some researchers have listed trust as a major characteristic of learning communities (Chen et al. 2007; Mayer et al. 1995; Rovai et al. 2004). Booth’s (2012) focus on online learning communities is one example of how trust is instrumental to the emotional strength of the learning group. “Research has established that trust is among the key enablers for knowledge sharing in online communities” (Booth 2012, p. 5). Related to trust is the feeling of being respected and valued within a community, which is often described as essential to a successful learning community (Lichtenstein 2005). Other authors describe this feeling of trust or respect as feeling “safe” within the community (Baker and Pomerantz 2000). For example, negative or ineffective learning communities have been characterized by conflicts or instructors who were “detached or critical of students and unable or unwilling to help them” (Lichtenstein 2005, p. 348).

Shared faith

Part of belonging to a community is believing in the community as a whole—that the community should exist and will be sufficient to meet the members’ individual needs. McMillan and Chavis (1986) felt that it was important that there be “a shared faith that members’ needs will be met through their commitment to be together” (p. 9). Rovai et al. (2004) agreed by saying that members “possess a shared faith that their educational needs will be met through their commitment to the shared goals and values of other students at the school” (p. 267).

These emotional boundaries not only define face-to-face learning communities, but they define virtual communities as well—perhaps more so. Because virtual communities do not have face-to-face interaction, the emotional bond that members feel with the persons beyond the computer screen may be even more important, and the emergence of video technologies is one method for increasing these bonds (Borup et al. 2014).

Community defined by vision

Communities defined by shared vision or sense of purpose are not as frequently discussed as boundaries based on relationships, but ways members of a community think about their group are important. Rather than feeling like a member of a community—with a sense of belonging, shared faith, trust, and interdependence—people can define community by thinking they are a community. They conceptualize the same vision for what the community is about, share the same mission statements and goals, and believe they are progressing as a community towards the same end. In short, in terms many researchers use, they have a shared purpose based on concepts that define the boundaries of the community. Sharing a purpose is slightly different from the affective concept of sharing faith in the existence of the community and its ability to meet members’ needs. Community members may conceptualize a vision for their community and yet not have any faith that the community is useful (e.g., a member of a math community who hates math). Members may also disagree on whether the community is capable of reaching the goal even though they may agree on what the goal is (“my well intentioned study group is dysfunctional”). Thus conceptual boundaries of a community of learners are distinct from relational ties; they simply define ways members perceive the community’s vision. Occasionally the shared conception is the most salient or distinguishing characteristic of a particular learning community.

Schrum et al. (2005) summarized this characteristic of learning communities by saying that a community is “individuals who share common purposes related to education” (p. 282). Royal and Rossi (1996) also described effective learning communities as rich environments for teamwork among those with a common vision for the future of their school and a common sense of purpose.

Community defined by function

Perhaps the most basic way to define the boundaries of a learning community is by what the members do. For example, a community of practice in a business would include business participants engaged in that work. This type of definition is often used in education which considers students members of communities simply because they are doing the same assignments: Participants’ associations are merely functional, and like work of research teams organized to achieve a particular goal, they hold together as long as the work is held in common. When the project is completed, these communities often disappear unless ties related to relationships, conceptions, or physical or virtual presence [access] continue to bind the members together.

The difference between functional boundaries and conceptual boundaries [boundaries of function and boundaries of vision or purpose] may be difficult to discern. These boundaries are often present simultaneously, but a functional community can exist in which the members work on similar projects but do not share the same vision or mental focus about the community’s purpose. Conversely, a group of people can have a shared vision and goals but be unable to actually work together towards this end (for example, if they are assigned to different work teams). Members of a functional community may work together without the emotional connections of a relational community, and members who are present in a community may occupy the same physical or virtual spaces but without working together on the same projects. For example, in co-working spaces, such as Open Gov Hub in Washington D.C., different companies share an open working space, creating in a physical sense a very real community, but members of these separate companies would not be considered a community according to functional boundaries. Thus all the proposed community boundaries sometimes overlap but often represent distinctive features.

The importance of functional cohesion in a learning community is one reason why freshman learning communities at universities usually place cohorts of students in the same classes so they are working on the same projects. Considering work settings, Hakkarainen et al. (2004) argued that the new information age in our society requires workers to be capable of quickly forming collaborative teams (or networked communities of expertise) to achieve a particular functional purpose and then be able to disband when the project is over and form new teams. They argued that these networked communities are increasingly necessary to accomplish work in the 21st Century.

Relying on functional boundaries to define a learning community is particularly useful with online communities. A distributed and asynchronously meeting group can still work on the same project and perhaps feel a shared purpose along with a shared functional assignment, sometimes despite not sharing much online social presence or interpersonal attachment.

Conclusion

Many scholars and practitioners agree that learning communities “set the ambience for life-giving and uplifting experiences necessary to advance an individual and a whole society” (Lenning and Ebbers 1999). Because learning communities are so important to student learning and satisfaction, clear definitions that enable sharing of best practices are essential. By clarifying our understanding and expectations about what we hope students will be able to do, learn, and become in a learning community, we can more precisely identify what our ideal learning community would be like and distinguish this ideal from the less effective/efficient communities existing in everyday life and learning.

In this chapter we have discussed definitions for four potential boundaries of a learning community. Two of these can be observed externally: access (Who is present physically or virtually?) and function (Who has been organized specifically to achieve some goal?). Two of these potential boundaries are internal to the individuals involved and can only be researched by helping participants describe their feelings and thoughts about the community: relationships (Who feels connected and accepted?) and vision (who shares the same mission or purpose?).

Researchers have discussed learning communities according to each of these four boundaries, and often a particular learning community can be defined by more than one. By understanding more precisely what we mean when we describe a group of people as a learning community—whether we mean that they share the same goals, are assigned to work/learn together, or simply happen to be in the same class—we can better orient our research on the outcomes of learning communities by accounting for how we erected boundaries and defined the subjects. We can also develop better guidelines for cultivating learning communities by communicating more effectively what kinds of learning communities we are trying to develop.

Application Exercises

- Evaluate your current learning community. How can you strengthen your personal learning community? Make one commitment to accomplish this goal.

- Analyze an online group (Facebook users, Twitter users, NPR readers, Pinners on Pinterest, etc.) that you are part of to determine if it would fit within the four proposed boundaries of a community. Do you feel like an active member of this community? Why or why not?

References

Baker, S., & Pomerantz, N. (2000). Impact of learning communities on retention at a metropolitan university. Journal of College Student Retention, 2(2), 115–126.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Blanchard, A. L., Welbourne, J. L., & Boughton, M. D. (2011). A model of online trust. Information, Communication & Society, 14(1), 76–106. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa8502.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Booth, S. E. (2012). Cultivating knowledge sharing and trust in online communities for educators. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 47(1), 1–31.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Borup, J., West, R., Thomas, R., & Graham, C. (2014). Examining the impact of video feedback on instructor social presence in blended courses. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(3). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1821.

Busher, H. (2005). The project of the other: Developing inclusive learning communities in schools. Oxford Review of Education, 31(4), 459–477. doi:10.1080/03054980500222221.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Cavanagh, M. S., & Garvey, T. (2012). A professional experience learning community for pre-service secondary mathematics teachers. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 37(12), 57–75.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Chen, Y., Yang, J., Lin, Y., & Huang, J. (2007). Enhancing virtual learning communities by finding quality learning content and trustworthy collaborators. Educational Technology and Society, 10(2), 1465–1471. Retrieved from http://dspace.lib.fcu.edu.tw/handle/2377/3722.

Clark, D. B. (1973). The concept of community: A re-examination. The Sociological Review, 21,397–416.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Davies, A., Ramsay, J., Lindfield, H., & Couperthwaite, J. (2005). Building learning communities: Foundations for good practice. British Journal of Educational Technology,36(4), 615–628. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8535.2005.00539.x.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Day, G., & Murdoch, J. (1993). Locality and community: Coming to terms with place. The Sociological Review, 41, 82–111.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Glynn, T. (1981). Psychological sense of community: Measurement and application. Human Relations, 34(7), 789–818.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Hakkarainen, K., Palonen, T., Paavola, S., & Lehtinen, E. (2004). Communities of networked expertise: Professional and educational perspectives. San Diego, CA: Elsevier.Google Scholar

Hillery, G. A. (1955). Definitions of community: Areas of agreement. Rural Sociology, 20, 111–123.Google Scholar

Kay, D., Summers, J., & Svinicki, M. (2011). Conceptualizations of classroom community in higher education: Insights from award winning professors. Journal of Ethnographic & Qualitative Research, 5(4), 230–245.Google Scholar

Kensler, L. A. W., Caskie, G. I. L., Barber, M. E., & White, G. P. (2009). The ecology of democratic learning communities: Faculty trust and continuous learning in public middle schools. Journal of School Leadership, 19, 697–735.Google Scholar

Lenning, O. T., & Ebbers, L. H. (1999). The powerful potential of learning communities: Improving education for the future, Vol. 16, No. 6. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report.Google Scholar

Lichtenstein, M. (2005). The importance of classroom environments in the assessment of learning community outcomes. Journal of College Student Development, 46(4), 341–356.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integration model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20, 709–734. doi:10.5465/amr.2007.24348410.Google Scholar

McMillan, D. W. (1996). Sense of community. Journal of Community Psychology, 24(4), 315–325.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 14(1), 6–23.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Rovai, A. P. (2002). Development of an instrument to measure classroom community. Internet & Higher Education, 5(3), 197.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Rovai, A. P., Wighting, M. J., & Lucking, R. (2004). The classroom and school community inventory: Development, refinement, and validation of a self-report measure for educational research. Internet & Higher Education, 7(4), 263–280.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Royal, M. A., & Rossi, R. J. (1996). Individual-level correlates of sense of community: Findings from workplace and school. Journal of Community Psychology, 24(4), 395–416.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Sarason, S. B. (1974). The psychological sense of community: Prospects for a community psychology. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.Google Scholar

Schrum, L., Burbank, M. D., Engle, J., Chambers, J. A., & Glassett, K. F. (2005). Post-secondary educators’ professional development: Investigation of an online approach to enhancing teaching and learning. Internet and Higher Education, 8, 279–289. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2005.08.001.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Shen, D., Nuankhieo, P., Huang, X., Amelung, C., & Laffey, J. (2008). Using social network analysis to understand sense of community in an online learning environment. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 39(1), 17–36. doi:10.2190/EC.39.1.b.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Shin, J. (2013). A community of peer interactions as a resource to prepare music teacher educators. Research and Issues In Music Education, 11(1). Retrieved from http://www.stthomas.edu/rimeonline/vol11/shin.htm.

Strike, K. A. (2004). Community, the missing element of school reform: Why schools should be more like congregations than banks. American Journal of Education, 110(3), 215–232. doi:10.1086/383072.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Watkins, C. (2005). Classrooms as learning communities: A review of research. London Review of Education, 3(1), 47–64.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Weissman, E., Butcher, K. F., Schneider, E., Teres, J., Collado, H., & Greenberg, D. (2011). Learning communities for students in developmental math: Impact studies at Queensborough and Houston Community Colleges. National Center for Postsecondary Research. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=1782120.

Zhao, C.-M., & Kuh, G. D. (2004). Adding value: Learning communities and student engagement. Research in Higher Education, 45(2), 115–138. doi:10.1023/B:RIHE.0000015692.88534.de.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

Dr. Richard E. West is an associate professor in the Department of Instructional Psychology & Technology at Brigham Young University, where he has taught since receiving his PhD in Educational Psychology and Instructional Technology from the University of Georgia. He researches social influences on creativity and innovation, online social learning, open badges and micro credentials, and K-16 technology integration. He is the co-founder of the Creativity, Innovation, and Design group at BYU (http://innovation.byu.edu) and co-developer of the BYU Ed Tech Badges (http://badgeschool.org). His research is available on Google Scholar, Academia.edu, and richardewest.com.

Dr. Richard E. West is an associate professor in the Department of Instructional Psychology & Technology at Brigham Young University, where he has taught since receiving his PhD in Educational Psychology and Instructional Technology from the University of Georgia. He researches social influences on creativity and innovation, online social learning, open badges and micro credentials, and K-16 technology integration. He is the co-founder of the Creativity, Innovation, and Design group at BYU (http://innovation.byu.edu) and co-developer of the BYU Ed Tech Badges (http://badgeschool.org). His research is available on Google Scholar, Academia.edu, and richardewest.com.

Gregory S. Williams is an instructional designer at intuit and the co-founder of Humanus Media, LLC, a video design company. He has previously worked as an instructional media designer for Brigham Young University (BYU) and a video marketing associate for Community Care College. He received his MA in instructional psychology and technology from BYU.

Gregory S. Williams is an instructional designer at intuit and the co-founder of Humanus Media, LLC, a video design company. He has previously worked as an instructional media designer for Brigham Young University (BYU) and a video marketing associate for Community Care College. He received his MA in instructional psychology and technology from BYU.