49

Strategies for Every Educational Technology Professional

Patrick R. Lowenthal, Joanna C. Dunlap, and Patricia Stitson

Editor’s Note: The following article was originally published in TechTrends and is used here by permission.

Lowenthal, P. R., Dunlap, J. C., & Stitson, P. (2016). Creating an intentional web presence: Strategies for every educational technology professional. TechTrends, 60, 320–329. doi:10.1007/s11528-016-0056-1

Abstract

Educators are pushing for students, specifically graduates, to be digitally literate in order to successfully read, write, contribute, and ultimately compete in the global market place. Educational technology professionals, as a unique type of learning professional, need to be not only digitally literate – leading and assisting teachers and students toward this goal, but also model the digital fluency expected of an educational technology leader. Part of this digital fluency involves effectively managing one’s web presence. In this article, we argue that educational technology professionals need to practice what they preach by attending to their own web presence. We share strategies for crafting the components of a vibrant and dynamic professional web presence, such as creating a personal website, engaging in social networking, contributing and sharing resources/artifacts, and attending to search engine optimization (SEO).

I recalled that someone worked on a similar project at McMillian Design Group. But when I did a search online, I couldn’t find anything about it…not even a contact… Frustrating, I was really hoping we could bring someone in to consult with us on this…

The group was finalizing plans for their conference keynote speaker. “It would be great to have a dynamic presenter speak on the topic of high impact educational practices.” “Yes, that’s perfect! Let’s get online and see if we can find anyone with that expertise. It would be great if we could preview sample slideshows, and maybe even an actual presentation on YouTube!”

It’s a busy Friday afternoon. Five members of a search committee are crammed into a room to screen 50 applications for an academic technology coordinator position. At first glance, all of the applicants appear to be qualified for the position. But the members of the search committee are really looking for someone who can support, lead, and inspire faculty at their institution. As the search committee screens the details of each application, one member turns to Google. She is interested to see what comes up from a quick search. Do applicants have a professional website? Do they engage with other professionals on social media?

All of these scenarios are likely familiar. For us, the search committee vignette really resonated. Over the years we have been on various search committees. Two things seemed to have happened with every search: dozens of applicants met the minimum qualifications, but very few applicants excited the search committee. When deciding whom to interview, members of the search committee often turned to Google. Our experience, though, is not unique. Research shows that employers regularly use the Internet to screen applicants (Davison et al. 2012; Reicher 2013; Stoughton et al. 2013). But unlike in the past where employers might only screen applicants to see if there is a reason not to hire someone, a growing number of employers screen applicants to find a reason why they should hire someone. For instance, a growing number of employers are simply looking for validation that an applicant is the professional that he or she claims to be (which Joyce 2014a, refers to as “social proof”); that is, these employers are looking to validate information found in an applicant’s cover letter and resume (see Driscoll 2013; Huhman 2014; Joyce 2014a, b). In fact, a growing number of employers report that they have found reasons to hire applicants as the result of an Internet search (see Careerbuilder.com 2006, 2009, 2012, 2014). Thus, we believe that one of the worst things that can happen for an applicant fighting for an interview is for a search committee to find nothing of substance about an applicant from an Internet search. Some people even believe that an empty Internet search suggests that an applicant is out-of-date and/or lazy, has nothing to share, or worse, has something to hide (Joyce 2014a, b; Mathews 2014); this is especially true for applicants in technology-focused disciplines (e.g., instructional design and technology, information technology, computer science, digital and graphic design) whose web presence also serves as reflections of their technology skills and dispositions.

For these reasons, intentionally creating a well-crafted web presence, and corresponding digital footprint, is important not only for recent graduates but for any professional in a community of practice that values technology use and innovation. In this article, we share our thoughts as to why educational technology professionals need to attend to their web presence and suggest a variety of ways in which they can begin crafting their online presence and intentionally shaping their digital footprints.

Background

Despite an ongoing tension over the years about the role of technology (see Lowenthal and Wilson 2010), the field of Educational Technology today is focused in large part on technology (e.g., digital learning, online learning, mobile learning, social networking and media). Further, reflecting how integrated and indispensable the Internet and social networks/media are in our lives as tools and spaces for information curation and communication (Fallows 2005; Yamamoto and Tanaka 2011), members increasingly use technology to connect, collaborate, and grow in social networks. Therefore, professionals in our field can no longer resist technology. Educational technology professionals must have a web presence in order to actively participate in the social discourse; compete with colleagues for positions and work; establish working and collaborative relationships with colleagues, clients, and stakeholders; and stay current in an ever-changing discipline. Educational technology professionals do not need to possess highly technical skills and abilities but they must be digitally-literate leaders who openly model their digital fluency and use it as a platform for creative practice and innovation. Being digitally literate and a member of a professional community of practice involves effectively managing one’s web presence (see Sheninger 2014).

Digital Literacy

Literacy is more than simply being able to read and write (Colombi and Schleppegrell 2002; Street 1995). Literacy today, as Koltay (2011) explained, involves “visual, electronic, and digital forms of expression and communication” (p. 214); this digital literacy includes a robust knowledge of the affordances and limitations of digital tools and strategies to address goals and needs in a variety of settings and contexts, plus the skill-set and disposition necessary for critical thinking, social engagement, and innovation (Fraser 2012). Digital literacy is much more than simply knowing how to use a computer or send a text message; a digitally literate professional is able to “adapt to new and emerging technologies quickly and pick up easily new semiotic language for communication as they arise” by embracing “technical, cognitive and social-emotional perspectives of learning with digital technologies, both online and offline” (Ng 2012, p. 1066). Graduates are now expected to be digitally literate as they enter the workforce (Jones and Flannigan 2006; Weiner 2011). As such, educators now have an added responsibility to help develop students’ digital literacy throughout their formal education (Van Ouytsel et al. 2014; see related literature on digital citizenship such as ISTE 2014; Hollandsworth et al. 2011; Ohler 2011). Educational technology professionals, as a distinct type of educational professional, must not only be digitally literate but also model their digital fluency, which in turn requires an advanced understanding of how people interact online, as well as varying digital-literacy skills.

Digital Footprint and Identity

An important, foundational aspect of being digitally literate involves being aware of and managing one’s digital footprint. A digital footprint, according to Hewson (2013), “outlines a person’s online activities, including their use of social networking platforms” (p. 14). A digital footprint is therefore created whenever we use networked technology. However, when left unattended, a digital footprint may fail to reflect what we want it to reflect about ourselves professionally, emphasizing only our personal interactions and activities. For example, during a recent faculty development workshop facilitated by the second author, a group of faculty were surprised that their personal Facebook pages, Pinterest boards, and/or Flickr photo collections came up on an Internet search before any professional content. If professional content did come up on the first page of their search, the associated pages were ones over which they had little direct control (e.g., their university faculty pages and their “Rate My Professor” entry). Each of these faculty had what is sometimes described as a digital shadow (Goodier and Czerniewicz 2015) or a passive digital footprint: a digital footprint “that grows with no deliberate intervention from an individual” (Madden et al. 2007, p. 3).

Educational technology professionals—as professionals who focus on the interface of technology and learning and often serve as digital leaders in their schools, colleges, and universities—must actively and intentionally shape their digital footprints. Doing so involves deciding what one’s digital footprint should say and/or represent in the first place. We all have multiple identities, at bare minimum a professional self and personal self. The key is to effectively manage our identities while still being authentic (for a discussion on maintaining personal and professional identities online see Henry 2012). We posit that a professional web presence can and should emphasize one’s best qualities (much like a résumé might) with accuracy and integrity, which in turn will actively shapes one’s digital footprint in a positive light.

Building one’s web presence (sometimes also referred to as “brand” or online “reputation”) and actively monitoring and intentional shaping one’s digital footprint is a popular topic these days (see Lowenthal and Dunlap 2012; Croxall 2014; Eyre et al. 2014; Goodier and Czerniewicz 2015; Microsoft n.d.). While very little formal research has been conducted to date on the positive benefits of a well-crafted web presence, people from various fields—such as Career Planning (Tucker 2014), Librarianship (Von Drasek 2011), the medical profession (Carroll and Ramachandran 2014; Greysen et al. 2010) to name a few—are talking about the importance of professionals taking control over their digital footprints by actively managing their web presence and therefore influencing the story that the Internet has to tell about them.

Pettiward and O’Reilly n.d.). What does your digital footprint say about you?

Strategies for Creating an Intentional Web Presence

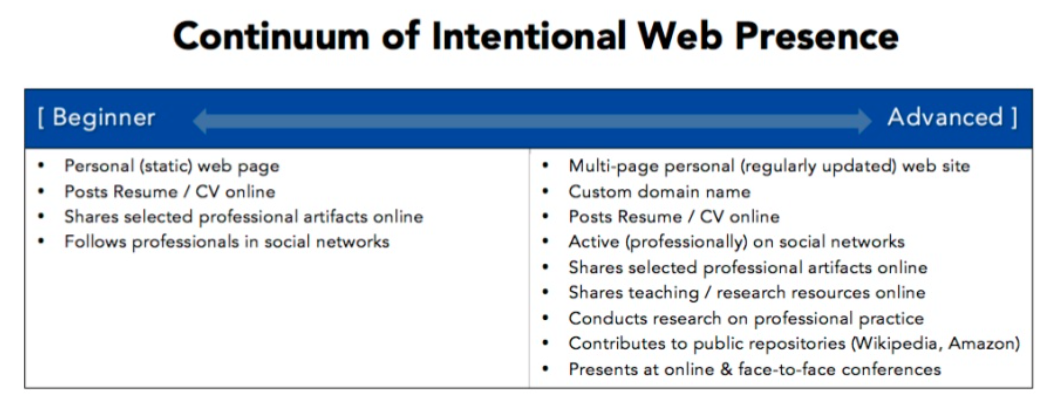

There is not one perfect way for creating a web presence for all educational technology professionals. There are many stages of adoption and levels of participation in creating an intentional web presence, ranging, for instance, from simply setting up a LinkedIn profile to actively blogging and engaging with others on popular social networks (see Fig. 1 for a visual illustration of what this continuum might look like). We will discuss some of these different ways of establishing a web presence in more depth in the following paragraphs. The first step to creating an intentional web presence, though, is to think about what information you feel comfortable publicly sharing, especially in light of your intended professional audience(s). If you think about your web presence as an instructional message about yourself with a designated audience or audiences (such as a teacher who may wish to consider multiple audiences, e.g., students, parents/guardians of students, colleagues, and administration), then you may consider what content about you is relevant to those audiences and to what level of detail and specificity you are comfortable sharing via a highly public distribution network. This information will be different for different professionals. The privacy of professionals as well as their employers must be taken into consideration; there are far too many examples of bullying and incivility on popular social networks (see Kowalski et al. 2014) as well as poor decisions made that resulted in someone losing their job (Poppick 2014). However, we believe that professionals should share aspects of their professional lives online with the larger professional community when they are permitted to do so. In the end, educational technology professionals should carefully and intentionally create their own web presence and its corresponding digital footprint, rather than leave it up to search engines like Google.

Figure. 1 Continuum of intentional web presence

Figure. 1 Continuum of intentional web presenceBelow we outline some common strategies to create an intentional web presence in order to participate in, contribute to, and benefit from the larger professional community of practice. The strategies we cover include creating a personal website, engaging in social networking, contributing and sharing resources/artifacts, and attending to search engine optimization (SEO). These strategies are based on our previous work and experience working with faculty and students to establish an intentional web presence (Dunlap and Lowenthal 2009a, 2009b, 2011; Lowenthal and Dunlap 2012), but are also supported by the work of others (e.g., Bozarth 2013, 2014; Goodier and Czerniewicz 2015; Posner et al. 2011; Sheninger 2014; Weller 2011).

Create a Personally Controlled Website

The first step in creating a web presence is establishing a base camp—a place that serves as a centralized hub of operation for all digital and online activity (see Marshall 2015; Sheninger 2014). While many professionals might have a personal webpage or even a multipage website on their employers’ servers, we recommend that educational technology professionals set up personally controlled websites that are separate from employer-sponsored sites. A personally controlled website is one that is under the full purview of the individual whose work the site is showcasing; it is also a website that will persist over time regardless of changes in employment, as well as help with search engine optimization, which will be discussed later on in this article (see Corbyn 2010 for an in-depth discussion on the value of a having a personally controlled website). A growing number of easy-to-use tools are available for creating professional-looking websites (e.g., Wix, Weebly, Google Sites, WordPress) for people without web development expertise.

A personally controlled website is also different than an ePortfolio created during and as a culminating comprehensive assessment in a postsecondary program. The ePortfolios created in university programs often include formative assessments of students’ progress during their coursework and a summative assessment—in lieu of a culminating, comprehensive exam—for evaluating the achievement of various performance standards (Lowenthal, White, and Cooley, 2011). While academic portfolios are often lauded as helpful in landing jobs after graduation, most academic portfolios are poor examples of showcase portfolios, in part because they tend to be littered with many things that employers are not interested in seeing, such as descriptions of coursework (see Bauer 2009; Clark 2011). Further, in our experience, graduates often do not understand the relevance of maintaining a portfolio of select and recent artifacts or of developing a web presence apart from an ePortfolio throughout their professional career.

Using a personally controlled website as a base camp for professional activity conducted online addresses several important web-presence goals:

- When participating in professional learning and sharing using social media and networking tools, it is helpful to have one central place to host and promote all professional activity.

- Having a base camp gives professionals a web presence that is under their control to ensure consistency and reliability over time; the professionals determine how they are presented professionally online, and when work and ideas are publicly shared.

- As professionals participate in social media and networking sites, they need a place to direct people to find out more about them and their work, and to stay connected. A base camp can help professionals accomplish this linkage.

- Having a base camp that allows professionals to post work and ideas (via blogging, for example) increases their ability to create and share content with others.

Your base camp represents where you are today. It states who you are, where you come from, and what your strongest skill sets are. If you are a contractor, a personal website establishes your relevance to the niche you work in. If you have a secure position, a personally controlled website can be an asset to establishing your status as a thought leader and valuable team member within your organization. In either situation, this online transparency inherently states that you have confidence in your own skill set, which in turn carries weight in many situations. We have found, though, that viewing your base camp as a static website is unrealistic. You should plan to update the website once every 6 months at minimum, whether you are in a secure job or not. Based on our experience working with others to create web presence and reviewing personally controlled websites of other professionals, a personally controlled website may include elements such as:

- Current personal statement

- Biography

- Resume or vita

- Philosophy on instructional design, technology integration, teaching, and/or research

- Curated resources and readings in support of professional learning and activities (knowledge of current forward thinking/lifelong learning)

- Influences

- Projects, products, and other showcased professional activities

- Testimonials, awards, and other professional achievements

- Contact information, including social networks participation

Your personally controlled website is your business card, your résumé, and so much more. In this sense, we believe that the look and feel of your personal website matters. You want to communicate to others that design and details matter—competencies that appear in position descriptions and employment announcements for educational technology professionals (Martin and Winzler 2008; Ritzhaupt et al. 2010). Therefore, you should purchase a personal domain name for your site and strive to avoid using common templates that are regularly used by others online. In our experience, common templates fail to highlight one’s personality or creativity; they can also feel dated over time and can undermine credibility as a digitally literate professional because they fail to illustrate design expertise. Also, when selecting a template, it is important to consider mobile friendliness as many professionals use their mobile devices to access online content. Here are a few examples of personally-controlled websites of educational technology professionals that we believe are aesthetically pleasing while still meeting web-presence goals:

- The eLearning Coach with Connie Malamed: http://theelearningcoach.com

- Daniel Stanfordad: http://danielstanford.com/index.html

- Jackie Van Nice: http://www.jackievannice.com

- Chris Perez: http://chriswgperez.com

Engage in Social Networking

The interest in and proliferation of networked social tools, technologies, and environments—exemplified by Facebook and Twitter—are affecting ways in which people use, create, and share information (Downes 2007; Veletsianos and Kimmons 2013; Veletsianos et al. 2013). Social networks and environments create a space for people to pursue transformational social and educational relations, collaboration, content creation, and work in general (Dunlap and Lowenthal 2011). By leveraging networked social tools, technologies, and environments, educational technology professionals may more robustly, creatively, and efficiently address educational needs, opportunities, and problems of practice (Joosten 2012). In addition, social networking has the potential to assist educational technology professionals in their pursuit of professional-learning opportunities (Dunlap and Lowenthal 2009a, 2009b, 2011); given that learning happens in a social context, the advent of social networking and media expands the social context for learning beyond formal classroom and training room settings (Brown and Adler 2008). In this way, the social context is no longer solely concentrated in a centralized location, but globally distributed (Kop and Hill 2008; Siemens 2008; Tapscott 2012). This expanding social context is very beneficial to educational technology professionals because it allows them to tap into expertise wherever it is and whenever it is needed or desired, creating a social network that is central to sustained lifelong learning (Couros 2010).

Regardless of the platform or the app, educational technology professionals need to consider how they use social networks to participate in, contribute to, and be inspired by the larger professional community. Professional organizations in the educational technology field all have some type of presence in each of the main social networking platforms, and may be a useful starting place for finding what Seth Godin termed as your tribe(s) (2008). Through social networking, educational technology professionals are able to engage in relevant discussions of problems of practice, share their expertise and current work with other practitioners, while at the same time learning from others (Dunlap and Lowenthal 2011). In our experience, social networking should be as much, if not even more, about networking as it is about broadcasting your latest work. Furthermore, being on every social networking platform is not necessary. We recommend that educational technology professionals start small and build their web presence. Part of establishing and maintaining a web presence involves knowing when and how to use available social networks. The following are three key social networks where educational technology professionals interact:

-

- Facebook: With over 800 million active users, Facebook in many ways is the social network. While Facebook remains a primarily “personal” social network where people connect with friends and family, educational technology professionals might interact with dozens of Facebook groups. See Table 1 for examples of Educational Technology Facebook Groups. You can search Facebook for other groups that might better align with your professional interests.

Table 1. Popular social networking groups

| Facebook Groups | LinkedIn Groups | Twitter Users / Groups |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

- LinkedIn: LinkedIn is often seen as a primarily professional space. Your LinkedIn site allows you to share the details of your professional status without muddying up your base camp with such details. While arguably the drier and most professional location of your online presence, many feel more comfortable participating on this site. In addition, countless groups where educational technology professionals interact are available. Table 1 includes three examples of LinkedIn Groups. There are dozens of other groups to choose from. You can begin searching here: https://www.linkedin.com/directory/groups/

- Twitter: Although Twitter may be seen as restrictive, given its 140-character-per-post limitation, Twitter offers educational technology professionals something Facebook and LinkedIn do not: an ability to follow someone without that person following you back. Further, Twitter enables professionals to carefully craft a diverse social network that might include professionals in related fields but who would not show up as members of specific Facebook or LinkedIn groups. In addition, Twitter’s hashtaging functionality is often used to support backchannel conversations between participants during conferences and other larger scale events, making it a valuable communication and collaboration tool. Table 1 includes a resource that lists over a 100 tweet chats. You can discover additional ones over time on Twitter.

Not sure where to begin on Twitter? Start by creating an account and following the tweets of professionals with similar interests. You can begin searching at https://twitter.com/search-advanced?lang=en. The following are some educational technology professionals who are very active on Twitter:

- Patti Shank @pattishank

- Mike Caulfield @holden

- Jane Bozarth @janebozarth

- George Velestianos @veletsianos

- Jesse Stommel @jessifer

- Bonnie Stewart @bonstewart

- Audrey Watters @audreywatters

- Martin Weller @mweller

- Vicki Davis @coolcatteacher

- Michael Feldstein @mfeldstein67

- George Siemens @gsiemens

- Steve Wheeler @timbuckteeth

- Bud Hunt @budtheteacher

- Alan Levine @cogdog

Another strategy is to follow the tweets of your colleagues, notable scholars and authors who have influenced your thinking and work, professional organizations of which you are a member, and organizations who produce tools and technologies you use on a regularbasis. In this way, you will more quickly experience the value of Twitter in support of your professional learning and work.

It is important to point out, though, that using social networking for professional purposes does not come naturally for everyone. For instance, some teachers face tensions using social networking for professional purposes (Kimmons and Veletsianos 2014, 2015) and others report the need for additional training and support (Joosten et al. 2013). With this in mind, some educational technology professionals strive to keep a clean separation between their personal and professional identities. If you wish to establish separate personal and professional social-networking accounts, you can use pseudonyms or generic handles (e.g., EdTech-Bob) to keep them separate. The disadvantage, though, of this approach is that it could diminish, if only a little, the web-presence goal of establishing yourself—under your name—as an active educational technology professional and thought leader.

Other notable online social networks include Academia (https://www.academia.edu) and Research Gate (https://www.researchgate.net): two popular social networks where academics share research they have conducted with the larger scholarly community. We posit that educational technology professionals, regardless of where they work, are in the educational research business. While scholarship—in the form of original empirical research—historically has been seen as strictly an academic pursuit of university professors and researchers, the increase in educational technology conferences and journals suggests that more and more educational technology professionals are conducting research of their own. Social networks like Academia and Research Gate help educational technology professionals stay in touch with current research conducted by others as well as to share any research that they might be conducting on their day-to-day practice.

Developing a web presence is not simply about having a website and only connecting with others online. Your web presence should be strengthened by and extend and elaborate on your overall engagement with the larger professional community of practice in face-to-face settings. Whenever possible, educational technology professionals should network face-to-face with other professionals in the field at conferences and workshops and through local chapters of national/international professional organizations. In other words, we have found that networking is not simply an online or face-to-face activity but rather an activity that should take advantage of and leverage the affordances of both types of networking because both enhance your professional presence.

Contribute, Share, and Use Others Instructional Resources/Artifacts

Educational technology professionals are constantly creating instructional resources and artifacts—some highly specific to a particular context, but others that are more generalizable and useful in a variety of contexts. And even with the rise of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), open educational resources (OER) (e.g., MERLOT, https://www.merlot.org and TeacherTube, http://www.teachertube.com), and the application of Creative Commons licensing (https://www.creativecommons.org), we have still found that too many educational technology professionals have not fully embraced the “culture of contribution” (Atkins et al. 2007, p. 3) and are not sharing, promoting, or seeking feedback from others outside of their organization about the things they create (see Bozarth 2013, 2014). Barriers to embracing a culture of contribution include concerns about proprietary work; intellectual property in a time of increased competition; merit evaluation processes that value copyrighted ideas in top-tiered journals and patents over social openness; and the ease-of-application of distilled, decontextualized learning objects (Atkins, Brown, and Hammond 2007; Hodgkinson-Williams and Gray 2009). However, given the forward-thinking nature of the educational technology domain and those professionals working in that domain, educational technology professionals should strive to share the results of their labor—the fine work they have produced that others may benefit from as well (see Tapscott 2012, for more on the value of sharing as a principle of openness in an open world). Shared resources may include white papers, application recommendations, program evaluations, reports of pilot studies, teaching and training materials, and creative works. These resources can be shared online via social media sharing sites such as YouTube, TeacherTube, SlideShare, Flickr, and even Amazon (e.g., through self-publishing as well as book and product reviews). Social media sharing sites offer an opportunity to share your expertise with a wider audience. Alternatively, there are many non social-media sites that allow you to open-access distribute your materials—such as Google Drive, Scribd, Box, Dropbox, and OneDrive—if conventional social media sites do not support the format and/or size of certain materials. If you are employed in a situation in which the work you produce is proprietary, then an appropriate solution may be to create an executive summary describing the work and its value, with screen shots or an excerpt if allowable.

Sharing resources and artifacts is good practice for a few reasons. First, selected artifacts can serve as a showcase portfolio that demonstrates your skills and abilities and areas of expertise. Second, sharing work online helps build collaborations with others. Third, sharing work online helps you further establish your digital footprint and present a clearer, more complete story about the work you do. Finally, via this type of sharing, you help to establish your credibility as an educational technology professional—the multiple resources and artifacts available allow the audience to triangulate cognitive authority, information quality, and overall relevance and value of your contributions to the professional community of practice (Hilligoss and Rieh 2008)—and may also enhance your employer’s credibility by association (Metzger 2007). The following social media sharing sites are popular, established, and full-featured, making them ideal for professional resource and artifact sharing:

- Merlot [http://www.merlot.org]: A place to share and find open educational resources.

- SlideShare [http://www.slideshare.com]: One of the largest sites to find and share presentations and other professional content.

- Flickr [https://www.flickr.com]: A photo sharing and photo management site.

- Pinterest [https://www.pinterest.com]: A great place to share and discover creative ideas.

- YouTube [http://www.youtube.com]: The largest site to find, watch, and share videos.

- TeacherTube [http://www.teachertube.com]: An online community for sharing instructional videos.

Content curation of others’ work is a key facet of professional web presence and can help you find your professional community of practice. Through curating the work of others, not only do you develop relationships with others, but you become a player in solving larger problems; you show that you are continuously learning and ever improving your skills. This transparency will help others realize your worth. And, of course, having access to others’ fine resources and artifacts can be helpful in your own work! Here are a few tools that you can use to start publicly curating content:

- Delicious [https://delicious.com]: A social bookmarking website to save, organize, and share web links.

- Diigo [https://www.diigo.com]: A social bookmarking website that is evolving into a larger knowledge management and curation website.

- Flipboard [https://flipboard.com/]: A content curation website.

- Paper.li [http://paper.li/]: A social, content-sharing and curation website.

- Pinterest [https://www.pinterest.com/]: A visual bookmarking tool.

- Scoop it [http://www.scoop.it]: A content curation website.

Attend to Search Engine Optimization (SEO)

Search Engine Optimization (SEO) is the process of improving the ability to locate and access work online from a specific set of search terms. SEO is one final but necessary component to crafting your web presence and intentionally shaping your digital footprint (Lowenthal and Dunlap 2012). Educational technology professionals need to improve the accessibility and reach of the work they share online by thinking about how people will find said work via an Internet search, and then making modifications to how work is presented online to increase the likelihood of others finding it online. This is an important aspect of web presence because—let’s face it—for individuals who rely on the Internet for professional learning and networking, if search engines like Google cannot find your work then it is inaccessible and does not fully contribute to the professional community of practice or enhance your web presence.

The most important rule of SEO is to create and share quality content. But another aspect of creating quality content is creating content that others find valuable and want to read and use. Creating and sharing similar and consistent content also helps boost your SEO. Thus, as an educational technology professional, you need to think about what you want to share and what you want to be known for. Then, carefully consider where you share your content as well as how you name and tag it. Some websites get more traffic than others, usually the more visitors the better when it comes to SEO and web presence. For instance, commercial websites like Youtube (100+ million monthly visits) and Slideshare (1.75 million monthly visits) get much more traffic than OER sites like MIT’s OpenCourseWare (200,000 monthly visits) and Merlot (17,000 monthly visits) (see Weller 2011). Therefore, sharing your work on high trafficked sites like these can help increase the SEO and overall visibility of your work, as can sharing the same work on multiple websites (e.g., sharing the same slide deck on Slideshare, Academia.edu, and your personally controlled website). Most social media and networking websites also give you some control over how you name, tag, and describe your work. A quick Internet search for similar work from other professionals can help you get a better idea of how best to name, describe, and tag your work.

Finally, we recommend that you spend some time tracking and analyzing the analytics on your personally controlled website (e.g., with Google Analytics) as well as various social networking and social media websites you might regularly use (e.g., Slideshare and Academia) to be better informed on which of your work is most valued by your professional community of practice. You should also spend time tracking topics online (e.g., with Google Alerts or Twitter #searches) that are important to your work so that you may continue to connect and collaborate with like-minded individuals.

Web Presence in Action

Patty’s Story

I understood the power of organic SEO and the importance of a well-designed website when I began my graduate studies in educational technology. In the small business I worked, I had revamped my employer’s website and presence in online directories. As I built more and more websites, I realized that, regardless of the amount of traffic a website has, ANY web presence would increase one’s Google ranking and searchability.

Armed with this knowledge and experience, I created an online professional portfolio to showcase some of the work I was doing in my graduate studies. At this point in my studies, I had two websites (patriciastitson.com and modestmedia.com) that were establishing my digital footprint when I began learning more about social media in my coursework. I setup a Twitter account ‘@imightwrite’, a YouTube and Vimeo account, and, of course, Facebook and LinkedIn. The coursework gave me an opportunity to take a hard look at my digital presence and relate it back to a personal learning network. As I was not a teacher or educator, the idea of a traditional personal learning network (PLN) was hard for me to put into practice. This is why I developed a twist on the model, marrying the principals of PLN with SEO to result in designing my social learning network. This is where content curation became crucial as that is how I ‘engaged’ with my community. By utilizing Scoop.it to post to both my blog and Twitter, I was able to quickly reach out and gain notice from people as far away as Norway. This is important to me as it establishes me as a lifelong learner and as a global citizen.

Conclusion

To be a successful, lifelong educational technology professional, you need to be digitally literate and model digital fluency in your day-to-day professional activities, including effectively managing your web presence. The strategies shared above will help you craft the components of a vibrant and dynamic professional web presence. However, we want to stress that there is no one right way for educational technology professionals to establish and maintain a web presence. As illustrated in Fig. 1 and previously discussed, you can tend to your web presence in multiple ways. Each professional needs to craft a web presence that is appropriate given the professional audience(s) she/he is trying to attract and connect with, and feels comfortable, authentic, and sustainable over time. Intentionally building a web presence takes time and effort; the key is doing it in a way that leads to positive results by taking control of the story the web tells about you.

Application Exercises

- Take a look at the elements that may be included on a personally controlled website and take a personal inventory. Which elements could you include on a website right now? What could you include with a little work? Which elements are you missing that you would like to have included, and how would you go about gaining the experience(s) to add to your website?

- Google yourself and use 3 or 4 of the ideas from this article to evaluate your current web presence.

References

Atkins, D. E., Brown, J. S., & Hammond, A. L. (2007). A review of the Open Educational Resources (OER) movement: Achievements, challenges, and new opportunities. Retrieved from http://www.hewlett.org/uploads/files/ReviewoftheOERMovement.pdf.

Bauer, R. (2009). Construction of one’s identity: A student’s view on the potential of eportfolios. In P. Baumgartner, S. Zauchner, & R. Bauer (Eds.), The potential of e-portfolios in higher education (pp. 173–183). Innsbruck: Studienverlag.

Google Scholar

Bozarth, J. (2013, May). Show your work. Training and Development. Retrieved from https://www.td.org/Publications/Magazines/TD/TD-Archive/2013/05/Show-Your-Work.

Bozarth, J. (2014). Show your work. San Francisco: Wiley.

Google Scholar

Brown, J. S., & Adler, R. P. (2008). Minds on fire: open education, the long tail, and learning 2.0. EDUCAUSE Review, 43(1), 16–20.

Google Scholar

Careerbuilder.com. (2006). One-in-four hiring managers have used Internet search engines to screen job candidates; one-in-ten have used social networking sites, careerbuilder.com survey finds. Retrieved from http://www.careerbuilder.com/share/aboutus/pressreleasesdetail.aspx?id=pr331&ed=12%2F31%2F2006&sd=10%2F26%2F2006.

Careerbuilder.com. (2009). Forty-five percent of employers use social networking sites to research job candidates, careerbuilder survey finds. Retrieved from http://www.careerbuilder.com/share/aboutus/pressreleasesdetail.aspx?id=pr519&sd=8/19/2009&ed=12/31/2009&siteid=cbpr&sc_cmp1=cb_pr519_&cbRecursionCnt=1&cbsid=8412d5b32ef54ce6854a035cf3a59d12-303995843-x3-6.

Careerbuilder.com. (2012). Thirty-seven percent of companies use social networks to research potential job candidates, according to new CareerBuilder Survey. Retrieved from http://www.careerbuilder.com/share/aboutus/pressreleasesdetail.aspx?id=pr691&sd=4%2F18%2F2012&ed=4%2F18%2F2099.

Careerbuilder.com (2014). Number of employers passing on applicants due to social media posts continues to rise, according to new careerbuilder survey. Retrieved from http://www.careerbuilder.com/share/aboutus/pressreleasesdetail.aspx?sd=6%2F26%2F2014&id=pr829&ed=12%2F31%2F2014.

Carroll, C. L., & Ramachandran, P. (2014). The intelligent use of digital tools and social media in practice management. Chest Journal, 145(4), 896–902.

CrossRef Google Scholar

Clark, D. (2011). E-portfolios: 7 reasons why I don’t want my life in a shoebox. Donald Clark Plan B. Retrieved from http://donaldclarkplanb.blogspot.com/2011/03/e-portfolios-7-reasons-why-i-dont-want.html.

Colombi, M. C., & Schleppegrell, M. J. (2002). Theory and practice in the development of advanced literacy. In M. J. Schleppegrell & M. C. Colombi (Eds.), Developing advanced literacy in first and second languages: Meaning with power (pp. 1–19). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Corbyn, Z. (2010). All about me, dot com. Times Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/features/all-about-me-dot-com/413005.article.

Couros, A. (2010). Developing personal learning networks for open and social learning. In G. Veletsianos (Ed.), Emerging technologies in distance education (pp. 109–128). Athabasca: Athabasca University Press.

Google Scholar

Croxall, B. (2014). How to overcome what scares us about our online identities. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/article/How-to-Overcome-What-Scares-Us/145967/.

Davison, H. K., Maraist, C. C., Hamilton, R. H., & Bing, M. N. (2012). To screen or not to screen? Using the Internet for selection decisions. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 24(1), 1–21.

CrossRef Google Scholar

Downes, S. (2007). Learning networks in practice. Institute for Information Technology, National Research Council Canada. Retrieved from https://nparc.cisti-icist.nrc-cnrc.gc.ca/npsi/ctrl?action=rtdoc&an=8913424.

Dunlap, J. C., & Lowenthal, P. R. (2009a). Horton hears a tweet. EDUCAUSE Quarterly, 32(4).

Dunlap, J. C., & Lowenthal, P. R. (2009b). Tweeting the night away: Using Twitter to enhance social presence. Journal of Information Systems Education, 20(2), 129–136.

Dunlap, J. C., & Lowenthal, P. R. (2011). Learning, unlearning, and relearning: Using Web 2.0 technologies to support the development of lifelong learning skills. In G. D. Magoulas (Ed.), Einfrastructures and technologies for lifelong learning: Next generation environments (pp. 292–315). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Driscoll, E. (2013). What your social media reputation says to employers. Fox Business. Retrieved from http://www.foxbusiness.com/personal-finance/2013/06/03/what-your-social-media-reputation-says-to-employers/.

Eyre, S., Lindsay, K., Noble, H., Edwards, A., & Paddock, A. (2014). Online presence: Developing your presence. Retrieved from https://weblearn.ox.ac.uk/access/content/group/e05e05d2-f4ce-4a24-a008-031832bd1509/LearningRes_Open/Course_Book_OnlinePresence_TWOD_developing_your_presence.pdf.

Fallows, D. (2005). Search engine users: Internet searchers are confident, satisfied and trusting—But they are also unaware and naïve. Report for the Pew Internet and American Life Project. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/2005/PIP_Searchengine_users.pdf.pdf.

Fraser, J. (2012). 20 ways of thinking about digital literacy in higher education. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/higher-education-network/blog/2012/may/15/digital-literacy-in-universities.

Godin, S. (2008). Tribes: We need you to lead us. New York: Portfolio/Penguin Group.

Google Scholar

Goodier, S., & Czerniewicz, L. (2015). Academics’ online presence guidelines: A four step guide to taking control of your visibility (3rd ed.). Retrieved from https://open.uct.ac.za/bitstream/handle/11427/2652/GoodierOnlinePresenceV3.pdf?sequence=11.

Greysen, S. R., Kind, T., & Chretien, K. C. (2010). Online professionalism and the mirror of social media. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25(11), 1227–1229.

CrossRef Google Scholar

Hargittai, E., & King, B. (2013). You need a website. Inside HigherEd. Retrieved from https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2013/11/11/essay-what-academic-job-seekers-need-their-websites.

Henry, A. (2012). Should I keep my personal and professional identities completely separate online? Lifehacker. Retrieved from http://lifehacker.com/5898370/should-i-keep-my-personal-and-professional-identities-completely-separate-online.

Hewson, K. (2013). What size is your digital footprint? A powerful professional learning network can give a boost to a new teaching career. Phi Delta Kappan, 94(7), 14.

CrossRef Google Scholar

Hilligoss, B., & Rieh, S. Y. (2008). Developing a unifying framework of credibility assessment: construct, heuristics, and interaction in context. Information Processing and Management, 44, 1467–1484.

CrossRef Google Scholar

Hodgkinson-Williams, C., & Gray, E. (2009). Degrees of openness: the emergence of open education resources at the University of Cape Town. International Journal of Education and Development using Information and Communication Technology (IJEDICT), 5(5), 101–116.

Google Scholar

Hollandsworth, R., Dowdy, L., & Donovan, J. (2011). Digital citizenship in K-12: it takes a village. TechTrends, 55(4), 37–47.

CrossRef Google Scholar

Huhman, H. R. (2014). 4 things employers look for when they Google you. Business Insider. Retrieved from http://www.businessinsider.com/why-employers-google-you-2014-5.

ISTE (n.d.). ISTE Standards: Students. Retrieved from https://www.iste.org/docs/pdfs/20-14_ISTE_Standards-S_PDF.pdf.

Jones, B., & Flannigan, S. L. (2006). Connecting the digital dots: literacy of the 21st century. EDUCAUSE Quarterly, 29(2), 8–10.

Google Scholar

Joosten, T. (2012). Social media for educators: Strategies and best practices. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Joosten, T., Pasquini, L., & Harness, L. (2013). Guiding social media at our institutions. Planning for Higher Education, 41(2), 125–135.

Google Scholar

Joyce, S. P. (2014). To land a job, know how employers use technology to hire. The Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/susan-p-joyce/job-search-technology_b_5037152.html.

Joyce, S. P. (2014). What 80% of employers do before inviting you for an interview. The Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/susan-p-joyce/job-search-tips_b_4834361.html.

Kimmons, R., & Veletsianos, G. (2014). The Fragmented educator 2.0: Social networking sites. Acceptable identity fragments, and the identity constellation. Computers & Education, 72, 292–301.

CrossRef Google Scholar

Kimmons, R., & Veletsianos, G. (2015). Teacher professionalization in the age of social networking sites. Learning, Media and Technology, 40(4), 480–501.

Koltay, T. (2011). The media and the literacies: media literacy, information literacy, digital literacy. Media, Culture & Society, 33(2), 211–221.

CrossRef Google Scholar

Kop, R., & Hill, A. (2008). Connectivism: Learning theory of the future or vestige of the past? International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 9(3). Retrieved from http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/viewArticle/523/1103.

Kowalski, R. M., Giumetti, G. W., Schroeder, A. N., & Lattanner, M. R. (2014). Bullying in the digital age: a critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 1073–1137.

CrossRef Google Scholar

Lowenthal, P., & Wilson, B. G. (2010). Labels do matter! A critique of AECT’s redefinition of the field. TechTrends, 54(1), 38–46.

Lowenthal, P. R., & Dunlap, J. C. (2012). Intentional web presence: Ten SEO strategies every academic should know. EDUCAUSE Review Online. Retrieved from http://www.educause.edu/ero/article/intentional-web-presence-10-seo-strategies-every-academic-needs-know.

Lowenthal, P., White, J. W., & Cooley, K. (2011). Remake/remodel: Using eportfolios and a system of gates to improve student assessment and program evaluation. International Journal of ePortfolio, 1(1), 61–70.

Madden, M., Fox, S., Smith, A., & Vitak, J. (2007). Online identify management and search in the age of transparency. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/2007/PIP_Digital_Footprints.pdf.pdf.

Marshall, K. (2015). How to maintain your digital identity as an academic. Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://m.chronicle.com/article/How-to-Curate-Your-Digital/151001/.

Martin, F., & Winzler, B. (2008). Multimedia competencies for instructional technologist. Paper presented at the UNC Teaching and Learning with Technology Conference, Raleigh, NC.

Mathews, J. (2014). Screen yourself in: 5 tips to make your online presence interview-worthy. TalentEgg. Retrieved from http://talentegg.ca/incubator/2014/07/09/screen-5-tips-online-presence-interviewworthy/.

Metzger, M. (2007). Making sense of credibility on the web: models for evaluating online information and recommendations for future research. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(13), 2078–2091.

CrossRef Google Scholar

Microsoft. (n.d.). Take charge of your online reputation. Microsoft. Retrieved from http://www.microsoft.com/security/online-privacy/reputation.aspx.

Ng, W. (2012). Can we teach digital natives digital literacy? Computers & Education, 59(3), 1065–1078.

CrossRef Google Scholar

Ohler, J. (2011). Digital citizenship means character education for the digital age. Kappa Delta Pi Record, 47, 25–27.

CrossRef Google Scholar

Pettiward, J., &. O’Reilly, C. (n.d.). Get clued up! Find yourself online. Retrieved from http://learning.londonmet.ac.uk/epacks/digital-literacies/findyourself.html.

Poppick, S. (2014). 10 social media blunders that cost a millennial a job – or worse. Money. Retrieved from http://time.com/money/3019899/10-facebook-twitter-mistakes-lost-job-millennials-viral/.

Posner, M., Varner, S., & Croxall, B. (2011). Creating your web presence: A primer for academics. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/blogs/profhacker/creating-your-web-presence-a-primer-for-academics/30458.

Reicher, A. (2013). Background of our being: internet background checks in the hiring process. The Berkeley Technology Law Journal, 28, 116–154.

Google Scholar

Ritzhaupt, A., Martin, F., & Daniels, K. (2010). Multimedia competencies for an educational technologist: a survey of professionals and job announcement analysis. Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 19(4), 421–449.

Google Scholar

Sheninger, E. (2014). Digital leadership: changing paradigms for changing times. Thousand Oaks: Corwin.

Google Scholar

Siemens, G. (2008). Learning and Knowing in Networks: Changing roles for Educators and Designers. Retrieved from https://itforum.coe.uga.edu/Paper105/Siemens.pdf.

Stoughton, J. W., Thompson, L. F., & Meade, A. W. (2013). Examining applicant reactions to the use of social networking websites in pre-employment screening. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30(1), 73–88.

CrossRef Google Scholar

Street, B. (1995). Social Literacies: Critical approaches to literacy development, ethnography and education. London: Longman.

Google Scholar

Tapscott, D. (2012). Four principles for the open world [transcript of TED Talk video]. Retrieved from http://www.ted.com/talks/don_tapscott_four_principles_for_the_open_world_1/transcript?language=en.

Tucker, K. (2014). Personal branding in career communications. Career Planning and Adult Development Journal, 30(2), 47–52.

Google Scholar

Van Ouytsel, J., Walrave, M., & Ponnet, K. (2014). How schools can help their students to strengthen their online reputations. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 87(4), 180–185.

CrossRef Google Scholar

Veletsianos, G., & Kimmons, R. (2013). Scholars and faculty members’ lived experiences in online social networks. The Internet and Higher Education, 16, 43–50.

CrossRef Google Scholar

Veletsianos, G., Kimmons, R., & French, K. D. (2013). Instructor experiences with a social networking site in a higher education setting: expectations, frustrations, appropriation, and compartmentalization. Educational Technology Research and Development, 61(2), 255–278.

CrossRef Google Scholar

Von Drasek, L. (2011). Hang in there: how to get a library job against all odds. School Library Journal, 57(2), 24–29.

Google Scholar

Weiner, S. (2011). Information literacy and the workforce: a review. Education Libraries, 34(2), 7–14.

Google Scholar

Weller, M. (2011). The digital scholar: How technology is transforming scholarly practice. New York: Bloomsbury.

CrossRef Google Scholar

Yamamoto, Y., & Tanaka, K. (2011). Enhancing credibility judgment of web search results. CHI’11 Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1235–1244). Association of Computing Machinery: New York.

Dr. Patrick R. Lowenthal is an assistant professor of educational technology at Boise State University (BSU). Prior to this, he worked as an instructional designer at BSU. He also worked for the University of Colorado Denver teaching online courses and supporting other faculty who taught online. He has a PhD in educational leadership and innovation, and a MAmaster’s in instructional design and technology from the University of Colorado Denver. He has also earned an MA in the academic study of religion from the University of Colorado Boulder and a BA in religion and philosophy from Georgia State University.

Dr. Patrick R. Lowenthal is an assistant professor of educational technology at Boise State University (BSU). Prior to this, he worked as an instructional designer at BSU. He also worked for the University of Colorado Denver teaching online courses and supporting other faculty who taught online. He has a PhD in educational leadership and innovation, and a MAmaster’s in instructional design and technology from the University of Colorado Denver. He has also earned an MA in the academic study of religion from the University of Colorado Boulder and a BA in religion and philosophy from Georgia State University.

Dr. Joanna C Dunlap is an associate professor at the University of Colorado Denver (UC Denver) School of Education & Human Development. She is also a senior faculty fellow for teaching at the Center for Faculty Development. Her research interests include the use of sociocultural approaches to enhance adult learners’ development and experience in post-secondary settings and effective teaching strategies for online education. She received her PhD in Educational Leadership and Innovation with an emphasis in Instructional Design and Technology from the University of Colorado Denver.

Dr. Joanna C Dunlap is an associate professor at the University of Colorado Denver (UC Denver) School of Education & Human Development. She is also a senior faculty fellow for teaching at the Center for Faculty Development. Her research interests include the use of sociocultural approaches to enhance adult learners’ development and experience in post-secondary settings and effective teaching strategies for online education. She received her PhD in Educational Leadership and Innovation with an emphasis in Instructional Design and Technology from the University of Colorado Denver. Patricia Stitson is an adjunct professor of management and information technologies at California International Business University. She is also a senior instructional designer and product manager at Learning Evolution, LLC. For decades she has worked in the field of instructional design with several companies, including hCentive, Chopra Center for Wellbeing, and Interact.Integrate. She received her MA in information and learning technologies from the University of Colorado at Denver.

Patricia Stitson is an adjunct professor of management and information technologies at California International Business University. She is also a senior instructional designer and product manager at Learning Evolution, LLC. For decades she has worked in the field of instructional design with several companies, including hCentive, Chopra Center for Wellbeing, and Interact.Integrate. She received her MA in information and learning technologies from the University of Colorado at Denver.