3 Egypt: Land of the Pharaohs

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- Identify key works of art and differentiate between the arts of Ancient Egypt.

- Define the pictorial and architectural conventions developed during the Early Dynastic and Old Kingdom periods in Egyptian art and recognize the subtle changes to the conventions of ancient Egyptian art during the Middle and New Kingdom periods.

Looking Forward

Egypt’s impact on later cultures was immense. You could say that Egypt provided the building blocks for Greek and Roman culture, and, through them, influenced all of the Western tradition. Today, Egyptian imagery, concepts, and perspectives are found everywhere; you will find them in architectural forms, on money, and in our day to day lives. Many cosmetic surgeons, for example, use the silhouette of Queen Nefertiti (whose name means “the beautiful one has come”) in their advertisements.

While today we marvel at the glittering treasures from the tomb of Tutankhamun, the sublime reliefs in New Kingdom tombs, and the serene beauty of Old Kingdom statuary, it is imperative to remember that the majority of these works were never intended to be seen—that was simply not their purpose. Ancient Egyptian art must be viewed from the standpoint of the ancient Egyptians to understand it. The somewhat static, usually formal, strangely abstract, and often blocky nature of much Egyptian imagery has, at times, led to unfavorable comparisons with later, and much more ‘naturalistic,’ Greek or Renaissance art. However, the art of the Egyptians served a vastly different purpose than that of these later cultures.

Ancient Egyptian civilization lasted for more than 3000 years and showed an incredible amount of continuity. While today we consider the Greco-Roman period to be in the distant past, it should be noted that Cleopatra VII’s reign (which ended in 30 BCE) is closer to our own time than it was to that of the construction of the pyramids of Giza. It took humans nearly 4000 years to build something—anything—taller than the Great Pyramids.

Egypt’s stability is in stark contrast to the Ancient Near East of the same period, which endured an overlapping series of cultures and upheavals with amazing regularity. The earliest royal monuments, such as the Narmer Palette carved around 3100 B.C.E., display identical royal costumes and poses as those seen on later rulers, even Ptolemaic kings on their temples 3000 years later.

A vast amount of Egyptian imagery, especially royal imagery that was governed by decorum, remained stupefyingly consistent throughout its history. This is why, especially to the untrained eye, their art appears extremely static—and in terms of symbols, gestures, and the way the body is rendered, it was. It was intentional. The Egyptians were aware of their consistency, which they viewed as stability, divine balance, and clear evidence of the correctness of their culture. This consistency was closely related to a fundamental belief that depictions had an impact beyond the image itself—tomb scenes of the deceased receiving food, or temple scenes of the king performing perfect rituals for the gods—were functionally causing those things to occur in the divine realm. If the image of the bread loaf was omitted from the deceased’s table, they had no bread in the Afterlife; if the king was depicted with the incorrect ritual implement, this could have dire consequences. This belief led to an active resistance to change in codified depictions.

These images, whether statues or relief, were designed to benefit a divine or deceased recipient. Statuary provided a place for the recipient to manifest and receive the benefit of ritual action. Most statues show a formal frontality, meaning they are arranged straight ahead, because they were designed to face the ritual being performed before them. Many statues were also originally placed in recessed niches or other architectural settings—contexts that would make frontality their expected and natural mode.

Statuary, whether divine, royal, or elite, provided a kind of conduit for the spirit (or ka) of that being to interact with the terrestrial realm. Divine cult statues (few of which survive) were the subject of daily rituals of clothing, anointing, and perfuming with incense and were carried in processions for special festivals so that the people could “see” them (they were almost all entirely shrouded from view, but their ‘presence’ was felt).

Generally, the works we see on display in museums were products of royal or elite workshops; these pieces fit best with our modern aesthetic and ideas of beauty. Most museum basements, however, are packed with hundreds (even thousands!) of other objects made for people of lower status—small statuary, amulets, coffins, and stelae (similar to modern tombstones) that are completely recognizable, but rarely displayed. These pieces generally show less quality in the workmanship; being oddly proportioned or poorly executed; they are less often considered ‘art’ in the modern sense. However, these objects served the exact same function of providing benefit to their owners (and to the same degree of effectiveness), as those made for the elite.

Three-dimensional representations, while being quite formal, also aimed to reproduce the real-world—statuary of gods, royalty, and the elite was designed to convey an idealized version of that individual. Some aspects of ‘naturalism’ were dictated by the material. Stone statuary, for example, was quite closed—with arms held close to the sides, limited positions, a strong back pillar that provided support, and with the fill spaces left between limbs. Wood and metal statuary[1], in contrast, was more expressive—arms could be extended and hold separate objects, spaces between the limbs were opened to create a more realistic appearance, and more positions were possible.

Two-dimensional art represented the world quite differently. Egyptian artists embraced the two-dimensional surface and attempted to provide the most representative aspects of each element in the scenes rather than attempting to create vistas that replicated the real world. Each object or element in a scene was rendered from its most recognizable angle and these were then grouped together to create the whole. This is why images of people show their face, waist, and limbs in profile, but eye and shoulders frontally. These scenes are complex composite images that provide complete information about the various elements, rather than ones designed from a single viewpoint, which would not be as comprehensive in the data they conveyed.

The Predynastic Period

The civilization of Egypt obviously did not spring fully formed from the Nile mud; although the massive pyramids at Giza may appear to the uninitiated to have appeared out of nowhere, they were founded on thousands of years of cultural and technological development and experimentation. “Dynastic” Egypt—sometimes referred to as “Pharaonic” which was the time when the country was largely unified under a single ruler, begins around 3100 B.C.E.

The period before this, lasting from about 5000 B.C.E. until unification, is referred to as Predynastic by modern scholars. Prior to this were thriving Paleolithic and Neolithic groups, stretching back hundreds of thousands of years, descended from northward migrating Homo erectus who settled along the Nile Valley. During the Predynastic period, ceramics, figurines, mace heads, and other artifacts such as slate palettes used for grinding pigments, begin to appear, as does imagery that will become iconic during the Pharaonic era—we can see the first hints of what is to come.

It is important to recognize that the dynastic divisions modern scholars use were not used by the ancients themselves. These divisions were created in the first Western-style history of Egypt, written by an Egyptian priest named Manetho in the 3rd century B.C.E. Each of the 33 dynasties included a series of rulers usually related by kinship or the location of their seat of power. Egyptian history is also divided into larger chunks, known as “kingdoms” and “periods,” to distinguish times of strength and unity from those of change, foreign rule, or disunity.

The Egyptians themselves referred to their history in relation to the ruler of the time. Years were generally recorded as the regnal dates (from the Latin regnum, meaning kingdom or rule) of the ruling king, so that with each new reign, the numbers began anew. Later kings recorded the names of their predecessors in vast “king-lists” on the walls of their temples and depicted themselves offering to the rulers who came before them—one of the best-known examples is in the temple of Seti I at Abydos.

These lists were often condensed, with some rulers (such as the contentious and disruptive Akhenaten) and even entire dynasties omitted from the record; they are not truly history, rather they are a form of ancestor worship, a celebration of the consistency of kingship of which the current ruler was a part.

Kings[2] in Egypt were complex intermediaries that straddled the terrestrial and divine realms. They were, obviously, living humans, but upon accession to the throne, they also embodied the eternal office of kingship itself. The ka, or spirit, of kingship was often depicted as a separate entity standing behind the human ruler. This divine aspect of the office of kingship was what gave authority to the human ruler. The living king was associated with the god Horus, the powerful, virile falcon-headed god who was believed to bestow the throne to the first human king.

The Old Kingdom (c. 2649–2130 B.C.E.)

The Old Kingdom was an incredibly dynamic period of Egyptian history. While the origin of many concepts, practices, and monuments can be traced to earlier periods, it was during the Old Kingdom that they developed into the forms that would characterize and influence the rest of pharaonic history. A number of broad artistic, historical, and religious trends distinguished this period. Yet, the specific elements and manifestations of these overarching commonalities changed dramatically over time, and the end of the Old Kingdom differed remarkably from the beginning. Although several important settlement sites provide some insight into everyday life, our knowledge of Old Kingdom material culture is largely based on funerary evidence.

The Old Kingdom is the name given to the period in the third millennium B.C.E. when Egypt attained its first continuous peak of civilization in complexity and achievement—the first of three so-called “Kingdom” periods which mark the high points of civilization in the lower Nile Valley (the others being Middle Kingdom and the New Kingdom). A period of political stability and economic prosperity, it is characterized by revolutionary advancements in royal funerary architecture. During the Old Kingdom, the king of Egypt became a living god, who ruled absolutely and could demand the services and wealth of his subjects. Both Egyptian society and the economy were greatly impacted by the organization of major state-sponsored building projects, which focused on building tombs for their kings. Indeed, the Old Kingdom is perhaps best known for the pyramids constructed at this time as pharaonic burial places, and, for this reason, the Old Kingdom is frequently referred to as the “Age of the Pyramids.”

Palette of King Narmer

Some artifacts are of such vital importance to our understanding of ancient cultures that they are truly unique and utterly irreplaceable. The Narmer Palette is so valuable that it has never been permitted to leave Egypt.

Discovered among a group of sacred implements ritually buried in a deposit within an early temple of the falcon god Horus at the site of Hierakonpolis (the capital of Egypt during the predynastic period), this large ceremonial object is one of the most important artifacts from the dawn of Egyptian civilization. The carved palette, more than 2 feet in height and made of smooth grey-green siltstone, is decorated on both faces with detailed low relief. These scenes show a king, identified by name as Narmer, and a series of ambiguous scenes that have been difficult to interpret and have resulted in a number of theories regarding their meaning.

The object itself is a monumental version of a type of daily use item commonly found in the predynastic period[3]. In addition to these simple, purely functional, palettes however, there were also a number of larger, far more elaborate palettes created in this period. These objects still served the function of being a ground for grinding and mixing cosmetics, but they were also carefully carved with relief sculpture. Many of the earlier palettes display animals —some real, some fantastic—while later examples, like the Narmer Palette, focus on human actions. Research suggests that these decorated palettes were used in temple ceremonies, perhaps to grind or mix makeup to be ritually applied to the image of the god. Later temple ritual included elaborate daily ceremonies involving the anointing and dressing of divine images; these palettes likely indicate an early incarnation of this process.

There are several reasons the Narmer Palette is considered to be of such importance. First, it is one of very few such palettes discovered in a controlled excavation. Second, there are a number of formal and iconographic characteristics appearing on the Narmer Palette that remain conventional in Egyptian two-dimensional art for the following three millennia: the way the figures are represented, the scenes being organized in regular horizontal zones known as registers, and the use of hieratic scale to indicate relative importance of the individuals. In addition, much of the regalia worn by the king, such as the crowns, kilts, royal beard, and bull tail, as well as other visual elements, such as the pose Narmer takes on one of the faces where he grasps an enemy by the hair and prepares to smash his skull with a mace, continue to be utilized from this time all the way through the Roman era.

The king is represented twice in human form, once on each face, followed by his sandal-bearer. He may also be represented as a powerful bull, destroying a walled city with his massive horns, in a mode that again becomes conventional—pharaoh is regularly referred to as “Strong Bull.”

In addition to the primary scenes, the palette includes a pair of fantastic creatures, known as serpopards—leopards with long, snaky necks—who are collared and controlled by a pair of attendants. Their necks entwine and define the recess where the makeup preparation took place. The lowest register on both sides includes images of dead foes, while both uppermost registers display hybrid human-bull heads and the name of the king. The frontal bull heads are likely connected to a sky goddess known as Bat and are related to heaven and the horizon. The name of the king, written hieroglyphically as a catfish and a chisel, is contained within a squared element that represents a palace facade.

There have been a number of theories related to the scenes carved on this palette. Some have interpreted the battle scenes as a historical narrative record of the initial unification of Egypt under one ruler, supported by the general timing (as this is the period of the unification) and the fact that Narmer sports the crown connected to Upper Egypt on one face of the palette and the crown of Lower Egypt on the other—this is the first preserved example where both crowns are used by the same ruler. Other theories suggest that, rather than an actual historical representation, these scenes were purely ceremonial and related to the concept of unification in general.

The scene showing Narmer wearing the Lower Egyptian Red Crown (with its distinctive curl) depicts him processing towards the decapitated bodies of his foes. The two rows of bodies are placed below an image of a boat preparing to pass through an open gate. This may be an early reference to the journey of the sun god in his boat. In later texts, the Red Crown is connected with bloody battles fought by the sun god just before the rosy-fingered dawn on his daily journey and this scene may well be related to this. It is interesting to note that the foes are shown as not only executed but rendered completely impotent—their castrated penises have been placed atop their severed heads.

On the other face, Narmer wears the Upper Egyptian White Crown as he grasps an inert foe by the hair and prepares to crush his skull. The White Crown is related to the dazzling brilliance of the full midday sun at its zenith as well as the luminous nocturnal light of the stars and moon. By wearing both crowns, Narmer may not only be ceremonially expressing his dominance over the unified Egypt, but also the early importance of the solar cycle and the king’s role in this daily process.

The Royal Crowns of Egypt

The Red Crown of Lower Egypt and the White Crown of Upper Egypt were the earliest crowns worn by the king and are closely connected with the unification of the country that sparks full-blown Egyptian civilization. The earliest representation of them worn by the same ruler is on the Narmer Palette, signifying that the king was ruling over both areas of the country. Soon after the unification, the fifth ruler of the First Dynasty is shown wearing the two crowns simultaneously, combined into one. This crown, often referred to as the Double Crown, remains a primary crown worn by pharaoh throughout Egyptian history. The separate Red and White crowns, however, continue to be worn as well and retain their geographic connections. There are a number of Egyptian words used for these crowns (nine for the White and 11 for the Red), but the most common—deshret and hedjet—refer to the colors red and white, respectively. It is from these identifying terms that we take their modern name. Early texts make it clear that these crowns were believed to be imbued with divine power and were personified as goddesses.

The Pyramid Complex at Giza

The last remaining of the Seven Wonders of the ancient world, the Great Pyramids of Giza are perhaps the most famous and discussed structures in history. These massive monuments were unsurpassed in height for thousands of years after their construction and continue to amaze and enthrall us with their overwhelming mass and seemingly impossible perfection. Their exacting orientation and mind-boggling construction have elicited many theories about their origins. However, by examining the several hundred years prior to their emergence on the Giza plateau, it becomes clear that these incredible structures were the result of many experiments, some more successful than others, and represent an apogee in the development of the royal mortuary complex.

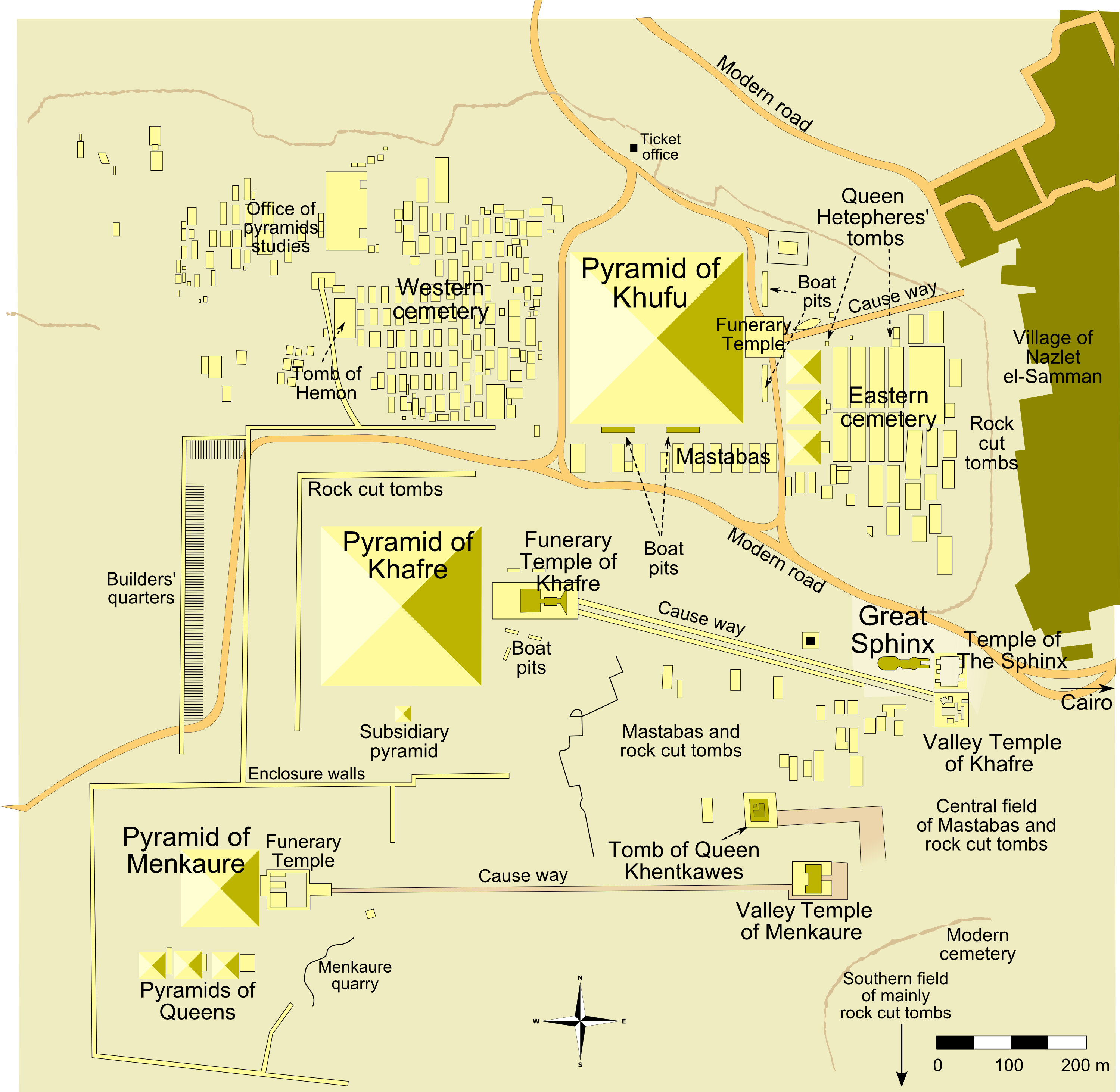

The three primary pyramids on the Giza plateau were built over the span of three generations by the rulers Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure. Each pyramid was part of a royal mortuary complex that also included a temple at its base and a long stone causeway (some nearly 1 kilometer in length) leading east from the plateau to a valley temple on the edge of the floodplain.

In addition to these major structures, several smaller pyramids belonging to queens are arranged as satellites. A major cemetery of smaller mastaba tombs fills the area to the east and west of the pyramid of Khufu and were constructed in a grid-like pattern for prominent members of the court. Being buried near the pharaoh was a great honor and helped ensure a prized place in the afterlife.

Egyptian Mastabas

Mastabas are a type of ancient Egyptian tomb in the form of a flat-roofed, rectangular structure with inward sloping sides, constructed out of mudbricks. During the Old Kingdom, royal mastabas eventually developed into rock-cut “step pyramids” and then “true pyramids,” although non-royal use of mastabas continued to be used for more than a thousand years. As the pyramids were constructed for the kings, mastabas for lesser royals were constructed around them. The interior walls of the tombs were decorated with scenes of daily life and funerary rituals. Because of the riches included in graves, tombs were a tempting site for grave-robbers. The increasing size of the pyramids is in part credited to protecting the valuables within, and many other tombs were built into rock cliffs in an attempt to thwart grave robbers.

The shape of the pyramid was a solar reference, perhaps intended as a solidified version of the rays of the sun. Texts talk about the sun’s rays as a ramp the pharaoh mounts to climb to the sky—the earliest pyramids, such as the Step Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara, were actually designed as a staircase. The pyramid was also clearly connected to the sacred ben-ben stone, an icon of the primeval mound that was considered the place of initial creation. The pyramid was considered a place of regeneration for the deceased ruler.

The Great Pyramid of Khufu, the largest of the three, rises to a height of 481 feet with a base length of more than 750 feet per side. The pyramid contains an estimated 2,300,000 blocks, some of which are upwards of 50 tons. The fine outer casing stones, which have long since been removed, were laid with great precision. These blocks of white Tura limestone would have given the pyramid a smooth surface and been quite bright and reflective. At the very top of the pyramid would have sat a capstone, known as a pyramidion, that may have been gilt. This dazzling point, shining in the intense sunlight, would have been visible for a great distance. The Pyramid of Khafre, the second of the Great Pyramids of Giza, has a section of outer casing that still survives at the very top.

Right next to the causeway leading from Khafre’s valley temple to the mortuary temple sits the first truly colossal sculpture in Egyptian history: the Great Sphinx. This massive depiction of a recumbent lion with the head of a king was carved for Khafre from living stone (directly from the bedrock of the Giza plateau), and it appears that the core blocks used to construct the king’s valley temple were quarried from the layers of stone that run along the upper sides of this massive figure.

The lion was a royal symbol as well as being connected with the sun as a symbol of the horizon; the fusion of this powerful animal with the head of the pharaoh was an icon that survived and was often used throughout Egyptian history. The king’s head is on a smaller scale than the body, which appears to have been due to a defect in the stone; a weakness recognized by the sculptors who compensated by elongating the body.

Directly in front of the Sphinx is a separate temple dedicated to the worship of its cult, but very little is known about it since there are no Old Kingdom texts that refer to the Sphinx or its temple. The temple is similar to Khafre’s mortuary temple and has granite pillars forming a colonnade around a central courtyard. However, it is unique in that it has two sanctuaries—one on the east and one on the west—likely connected to the rising and setting sun.

The third of the major pyramids at Giza belongs to Menkaure. This is the smallest of the three, rising to a height of 213 feet, but the complex preserved some of the most stunning examples of sculpture to survive from all of Egyptian history. Menkaure’s pyramid chambers are more complex and include a chamber carved with decorative panels and another chamber with six large niches. The burial chamber is lined with massive granite blocks.

Within Menkaure’s mortuary and valley temples, neither of which were completed before his death, excavation revealed a series of statues of the king. The stunning dyad, of the king with his primary queen, Khamerernebty II (now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), as well as a number of triads showing the king being embraced by various deities, were discovered in the valley temple and were originally set up surrounding the open court.

Rather than serving as realistic portraits of their patrons, Egyptian funerary statues such as that of Menkaure and his queen from the Fourth Dynasty were meant to serve as eternal homes for the spirit of the deceased, or the ka. Although the mummified body of the deceased was intended to last forever, these figures, carved in exceptionally hard stone, were meant to provide a more permanent and guaranteed home for the ka, should anything happen to the mummified body. In this example, Menkaure is shown striding forward with his hands clenched alongside his idealized youthful, muscular body, which conforms to the same Egyptian ideals visible in the Palette of Narmer. Menkaure’s stance here is indicative of power, with one foot placed slightly ahead of the other. The positioning of his wife, with her hand on her husband, speaks to their marital status. As was common in Egyptian statuary, the figures are not fully freed from the stone blocks, reflecting an interest in permanence. As in the Palette of Narmer, the figure of the pharaoh and his wife are idealized, rather than naturalistic, evidenced by their stiff and generalized features, and abstracted anatomy.

The Middle Kingdom (c. 2030–1650 B.C.E.)

The Middle Kingdom designates a period of ancient Egyptian civilization stretching from approximately 2030 to 1650 B.C.E. (Dynasty 11 through Dynasty 13). During this era, the cultural principles set out at the beginning of Egyptian civilization and codified during the Old Kingdom were reimagined, including the ideology of kingship, the organization of society, religious practices, afterlife beliefs, and relations with neighboring peoples. These transformations are attested to in architecture, sculpture, painting, relief decoration, stelae, jewelry, personal possessions, and literature.

Many Middle Kingdom monuments are poorly preserved, which contributes to the era’s relative lack of modern prominence. Because Egyptian temples dedicated to deities were often replaced by succeeding kings, almost no Middle Kingdom temples remain standing. Many Middle Kingdom pyramids were constructed with mud-brick cores that eroded after their limestone casing was removed by ancient stone robbers. The construction of pyramids declined toward the end of the Twelfth Dynasty, as instability led to the decline of the Middle Kingdom.

Temple of Amun-Re and the Hypostyle Hall, Karnak

While there is evidence that Old Kingdom pharaohs contributed artworks to temples dedicated to deities, royal patronage of such monuments expanded considerably in the Middle Kingdom. Particularly during the reign of Senwosret I, we find the first substantial remains of god’s temples with stone walls, extensive relief decoration, and sculpture programs. Thebes witnessed the inception of one of the greatest temples of ancient Egypt, the Karnak complex, dedicated to the increasingly powerful god Amun. The presence of deity temples in important locations throughout Egypt can also be understood to unify the populace and stress the king’s dominant role in regional centers.

The massive temple complex of Karnak was the principal religious center of the god Amun-Re in Thebes during the New Kingdom (which lasted from 1550 until 1070 B.C.E.). The complex remains one of the largest religious complexes in the world. However, Karnak was not just one temple dedicated to one god—it held not only the main precinct to the god Amun-Re—but also the precincts of the gods Mut and Montu. Compared to other temple compounds that survive from ancient Egypt, Karnak is in a poor state of preservation, but it still gives scholars a wealth of information about Egyptian religion and art.

The site was first developed during the Middle Kingdom (2055-1650 B.C.E.) and was initially modest in scale but as new importance was placed on the city of Thebes, subsequent pharaohs began to place their own mark on Karnak. The main precinct alone would eventually have as many as twenty temples and chapels. Karnak was known in ancient times as “The Most Select of Places” (Ipet-isut) and was not only the location of the cult image of Amun and a place for the god to dwell on earth but also a working estate for the priestly community who lived on site. Additional buildings included a sacred lake, kitchens, and workshops for the production of religious accouterments.

The main temple of Amun-Re had two axes—one that went north/south and the other that extended east/west. The southern axis continued towards the temple of Luxor and was connected by an avenue of ram-headed sphinxes.

While the sanctuary was plundered for stone in ancient times, there are still a number of unique architectural features within this vast complex. For example, the tallest obelisk in Egypt stood at Karnak and was dedicated by the female pharaoh Hatshepsut who ruled Egypt during the New Kingdom. Made of one piece of red granite, it originally had a matching obelisk that was removed by the Roman emperor Constantine and re-erected in Rome. Another unusual feature was the Festival Temple of Thutmose III, which had columns that represented tent poles, a feature this pharaoh was no doubt familiar with from his many war campaigns.

One of the greatest architectural marvels of Karnak is the hypostyle hall built during the Ramesside period. The hall has 134 massive sandstone columns with the center twelve columns standing at 69 feet. Like most of the temple decoration, the hall would have been brightly painted and some of this paint still exists on the upper portions of the columns and ceiling today. With the center of the hall taller than the spaces on either side, the Egyptians allowed for clerestory lighting. In fact, the earliest evidence for clerestory lighting comes from Egypt. Not many ancient Egyptians would have had access to this hall, since the further one went into the temple, the more restricted access became.

Conceptually, temples in Egypt were connected to the idea of zep tepi, or “the first time,” the beginnings of the creation of the world. The temple was a reflection of this time, when the mound of creation emerged from the primeval waters. The pylons, or gateways in the temple represent the horizon, and as one moves further into the temple, the floor rises until it reaches the sanctuary of the god, giving the impression of a rising mound, like that during creation. The temple roof represented the sky and was often decorated with stars and birds. The columns were designed with lotus, papyrus, and palm plants in order to reflect the marsh-like environment of creation. The outer areas of Karnak, which was located near the Nile River, would flood during the annual inundation—an intentional effect by the ancient designers no doubt, in order to enhance the temple’s symbolism.

During the Middle Kingdom, monumentality achieved a greater balance between architecture and sculpture. While large temples, pyramid complexes, and tomb superstructures were built, none of these buildings had the same massiveness as their Old or New Kingdom counterparts. At the same time, over-life-size and monumental sculptures—largely, though not exclusively, depicting the pharaoh—became widespread. Monumentality was a device used by Middle Kingdom kings to stress their dominion over the entire country.

The New Kingdom (c. 2030–1650 B.C.)

Known especially for monumental architecture and statuary honoring the gods and pharaohs, the New Kingdom, a period of nearly 500 years of political stability and economic prosperity, also produced an abundance of artistic masterpieces created for use by non-royal individuals.

The New Kingdom was a prosperous and stable era following the reunification of Egypt after the tumultuous Second Intermediate Period. It is marked by increasingly complex and monumental building projects that were filled with statuary, painted images, and wall reliefs. Looking more closely at such architectural monuments can make it clearer how artworks now found in museums were originally part of larger architectural complexes and were intended to be seen with other visual images. Starting with Hatshepsut, buildings were of a grander scale than anything previously seen in the Middle Kingdom.

The Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut

The interrelation of ceremony and images can be seen with the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, who is the first recorded female monarch in history. The temple, carved out of the living rock face, is a notable change from the use of pyramids in the Old Kingdom but has an equally monumental effect, with its massive colonnaded terraces. This incredible complex was one of several building projects executed by the female pharaoh, evidencing a desire to use art as propaganda to affirm her power and status (which was even more pivotal to her reign as a female monarch). Within the massive complex, painted reliefs celebrate the female ruler, emphasize her divine birth, and highlight her achievements.

The focal point of the mortuary temple’s tomb was the Djeser-Djeseru, a colonnaded structure of perfect harmony that predates the Parthenon by nearly one thousand years. Built into a cliff face, Djeser-Djeseru, or “the Sublime of Sublimes,” sits atop a series of terraces that once were graced with lush gardens.

Statues showing the queen making offerings to the gods, lined the entry to the temple and were found throughout the complex. Other statues depicted her as a sphinx or as Osiris, god of the afterlife. These multiple images of the queen reinforce her associations with the gods and her divine birth, as well as her absolute power as pharaoh. The multiplication of images of the monarch in different roles can later be compared to Augustus’ use of statuary in the Roman Empire.

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut and Large Kneeling Statue

The Atenist Revolution: Art of the Amarna Period

Shortly after coming to the throne, the new pharaoh Amenhotep IV, a son of Amenhotep III and Queen Tiye, established worship of the light that is in the orb of the sun (the Aten) as the primary religion, and the many-armed disk became the omnipresent icon representing the god. The new religion, with its emphasis on the light of the sun and on what can be seen, coexisted with a new emphasis on time, movement, and atmosphere in the arts[4]. Exceptional as the new outlook seems, it certainly had roots in the increasing prominence of the solar principle, or Re, in the earlier Dynasty 18, and in the emphasis on the all-pervasive quality of the god Amun-Re, developments reaching a new height in the reign of Amenhotep III (ca. 1390–1353 B.C.). Likewise, artistic changes were afoot before the reign of Amenhotep IV / Akhenaten. For example, Theban tombs of Dynasty 18 had begun to redefine artistic norms, exploring the possibilities of line and color for suggesting movement and atmospherics or employing more natural views of parts of the body.

While the art and texts of what is commonly called the Amarna Period after the site of the new city for the Aten are striking, and their naturalistic imagery is easy to appreciate, it is more difficult to bring the figure of Amenhotep IV / Akhenaten himself or the lived experiences of Atenism into focus. The courtiers who helped the king monumentalize his vision refer to a kind of teaching that the king provided, to them at a minimum, and the art and particular hymns or prayers convey a striking appreciation of the physical world.

Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and Three Daughters

The style of sculpture shifted drastically during the Amarna Period in the late Eighteenth Dynasty, when Pharaoh Akhenaten moved the capital to the city of Amarna. This art is characterized by a sense of movement and activity in images, with figures having raised heads, many figures overlapping, and many scenes full and crowded. Sunken relief was widely used. Figures are depicted less idealistically and more realistically, with an elongation and narrowing of the neck; sloping of the forehead and nose; prominent chin; large ears and lips; spindle-like arms and calves; and large thighs, stomachs, and hips.

For example, many depictions of Akhenaten’s body show him with wide hips, a drooping stomach, thick lips, and thin arms and legs. This is a divergence from the earlier Egyptian art which shows men with perfectly chiseled bodies, and there is generally a more “feminine” quality in male figures. Some scholars suggest that the presentation of the human body as imperfect during the Amarna period is in deference to Aten.

Like previous works, faces on reliefs continued to be shown exclusively in profile. The illustration of figures’ hands and feet showed great detail, with fingers and toes depicted as long and slender. The skin color of both males and females was generally dark brown, in contrast to the previous tradition of depicting women with lighter skin. Along with traditional court scenes, intimate scenes were often portrayed. In a relief of Akhenaten, he is shown with his primary wife, Nefertiti, and their children in an intimate setting. His children are shrunken to appear smaller than their parents, a routine stylistic feature of traditional Egyptian art.

Thutmose’s Bust of Nefertiti

Possibly even Akhenaten’s last years and certainly the period after his death give evidence of a troubled succession. Nefertiti, Meritaten, the mysterious pharaoh Smenkhkare, and the female pharaoh Ankhetkhepherure—for whom the chief candidates in discussions so far have been Nefertiti and Meritaten, the eldest daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti—and ultimately Tutankhaten (Tutankhamun) all have roles. Energetic scholarly discussion of the events of this period and the identity, parentage, personal history, and burial place of many members of the Amarna royal family is ongoing. It is clear that already during the succession period, there was some rapprochement with Amun’s adherents at Thebes. With the reign of Tutankhaten / Tutankhamun, the royal court left Akhetaten and returned to Memphis; traditional relations with Thebes were resumed and Amun’s priority fully acknowledged. With Haremhab, Akhenaten’s constructions at Thebes were dismantled, and dismantling began at Amarna. Apparently in the reign of Ramesses II, the formal buildings of Akhetaten were completely destroyed, and many of their blocks reused as matrix stone in his constructions at Hermopolis and elsewhere. The site had presumably been abandoned.

- For more information, see the articles "Materials and techniques in ancient Egyptian art" and “Aspects of Color in Ancient Egypt”. ↵

- Use of the term "king" can be problematic when discussing the dynastic history of Ancient Egypt, as the word implies male rulership. While most of the rulers of Egypt were male, there are at least two notable exceptions within the Dynastic Era: Sobekneferu of the twelfth dynasty and Hatshepsut of the eighteenth-dynasty. The neutral terms 'ruler' and 'pharaoh', or the official titles 'Nsw-bity' (He of the Sedge and Bee [the symbols of Upper and Lower Egypt]) and 'Nb-tawy' (Lord of the Two Lands) are more commonly preferred in the field of Egyptology. ↵

- Palettes were generally flat, minimally decorated stone objects used for grinding and mixing minerals for cosmetics. Dark eyeliner was an essential aspect of life in the sun-drenched region; like the dark streaks placed under the eyes of modern athletes, black cosmetic around the eyes served to reduce glare. Basic cosmetic palettes were among the typical grave goods found during this early era. ↵

- In the video "Akhenaten, Nefertitim and Three Daughters", a statement is made that "Akhentaten was a monotheist", which is an over-simplification of the nature of Atenist philosophy as presented by Akhenaten during his reign. The full nature of Atenism is still widely unclear, but the general consensus is that it was either monolotry or henotheism (systems of worship in which there is a belief in the existence of many gods, but consistent worship of a singular, divine entity). Amenhotep IV/Akhenaten was not born as heir apparent to the throne of Egypt; that role originally fell upon his older brother, Thutmose, who unfortunately met with an early death. As the second-eldest, young Amenhotep IV would have entered the priesthood for religious training. It is from this context that he begins to assert that the worship of many deities is redundant, since they are all aspects of the sun in one form or another. Therefore, we should only devote our time and energy to the devotion of the physical solar disk (Aten) itself. ↵

a sense of what was ‘appropriate’.

after "pharaoh," the Greek title of the Egyptian kings derived from the Egyptian title per-aA, "Great House"

the proposed extinct species of the human lineage that lived throughout most of the Pleistocene Epoch, having upright stature and a well-evolved post-cranial skeleton, but with a smallish brain, low forehead, and protruding face: the first fossil specimen was discovered in Indonesia in 1891.

an ancient Egyptian pharaoh reigning c. 1353 - 1334 BC, the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Before the fifth year of his reign, he was known as Amenhotep IV.

also known as bas-relief, a projecting image with a shallow overall depth. A coin is a good example of relief sculpture: the inscription, the date, and the figure--sometimes a portrait—are slightly raised above a flat surface.

the ancient Egyptian god of war and is often depicted with the head of a falcon or a bull.

(pronounced moot) a primordial goddess associated with motherhood. She was at times referred to as mother of the earth and as mother of the gods.

a principal god of ancient Egypt; a composite of the god Amun, the patron of Thebes, and the Sun god, Re.

a very tall four-sided stone that tapers upward and is topped with a pyramid shape. Each side is often heavily inscribed with hieroglyphs. The stone is often a single piece of granite. The obelisk from Karnak (now in Rome) is estimated to weigh more than 900,000 pounds.

a space with a roof supported by columns

the period when Egypt was ruled by the eleven pharaohs named Ramses.

a section of wall that allowed light and air into the otherwise dark space below