Iconography of Authority: Depicting Power in the Ancient World

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Define the concept of iconography and identify several ways through which rulers have promoted their political authority through art.

- Demonstrate your ability to interpret the political iconography within a work of art.

Looking Forward

From the earliest of history to the modern period, works of art and architecture have been designed to convey the power of rulers. While the following examples will often rely on a shared visual vocabulary to suggest power — including expensive materials, large size, and hieratic scale — each example draws on its own culture for the most basic idea of what it means to be powerful, and each will express these ideas in its own fashion. In one culture, violence might be the hallmark of power, whereas in another support from the masses might be more important.

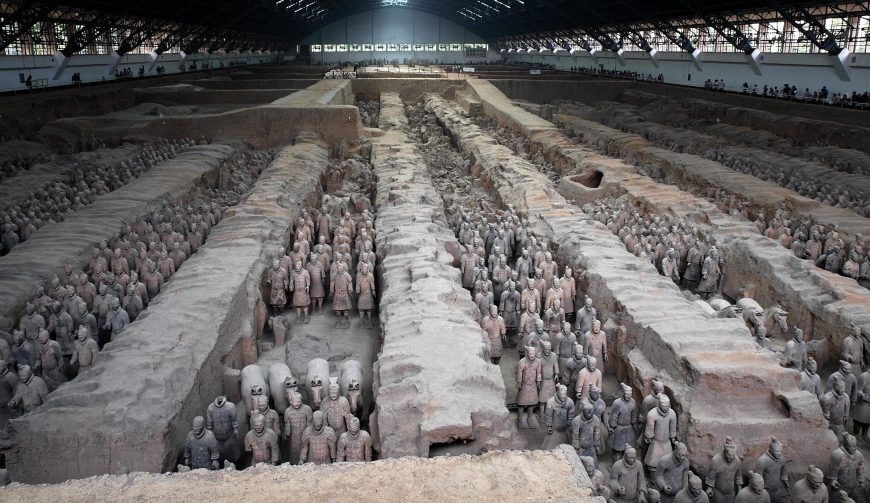

Spotlight: Terracotta Army of Emperor Qin Shi Huangdi

The first emperor of China was Qin Shi Huangdi. First, he became king of the Qin (pronounced “Chin”) state at the age of thirteen. Eventually he defeated the rulers of all the competing Chinese states, unifying China and declaring himself “First Emperor of the Qin Dynasty” (Qin Shi Huangdi). He began the construction of his vast tomb as soon as he took the throne, and it took 38 years to finish, even with a reported 700,000 convicts laboring for the last 13 years of construction. These great numbers are, themselves, displays of the tremendous power of the emperor, and the work clearly bears the imprint of their astounding labors.

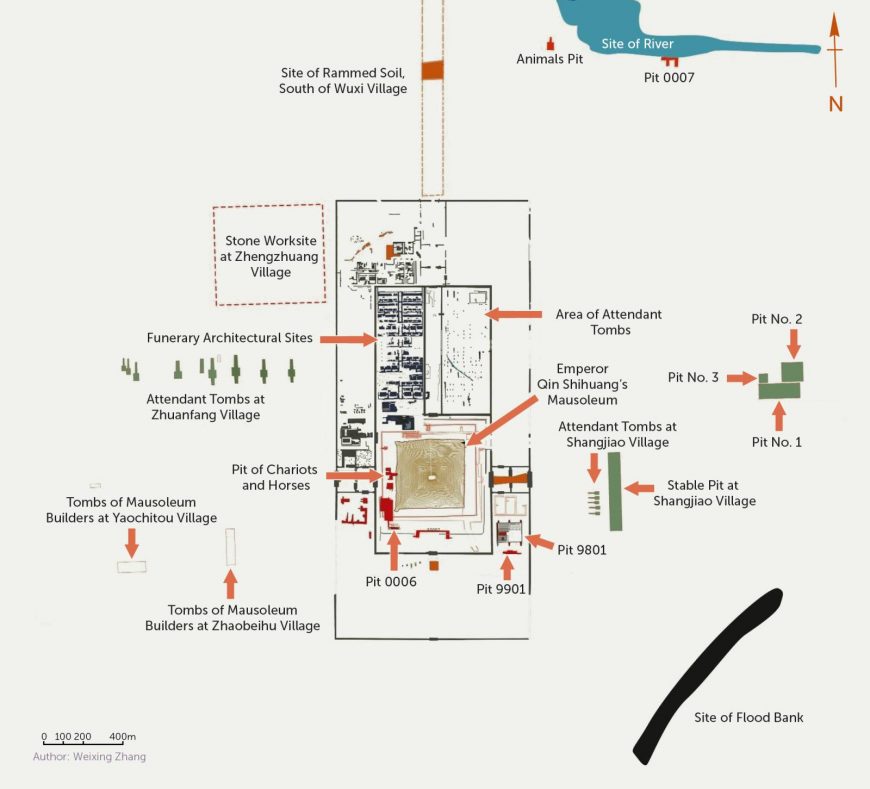

Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor

No doubt thousands of statues still remain to be unearthed at this archaeological site, which was not discovered until 1974. Qin (d. 210 B.C.), the first unifier of China, is buried, surrounded by the famous terracotta warriors, at the centre of a complex designed to mirror the urban plan of the capital, Xianyan. The small figures are all different; with their horses, chariots and weapons, they are masterpieces of realism and also of great historical interest.

As emperor, he was repressive —banning and burning Confucian books and executing the scholars who wrote and studied them. Not surprisingly there were at least two attempts to assassinate him.

When the tomb was completed, it was covered in grass and trees, so that it would appear like a natural part of the landscape. Today, from the outside, Qin Shi Huangdi’s burial mound looks like a hill. This explains how the huge tomb could have remained hidden until 1974 when rural villagers accidentally discovered it while digging a well. It blended into its surroundings, looking like a foothill of the Li Mountains.

As the plan of the tomb complex shows, the tomb itself was surrounded by a large number of other burials, including three pits containing warriors made from terracotta (which are known today as the “Terracotta Army”) There was also a pit filled with the remains of exotic animals, and the graves of followers executed at the time of the burial. So far, approximately 7,000 figures made from terracotta and 100 wooden chariots have been discovered in Pits 1, 2 and 3.

When we look at the vast rows of the 6,000 soldiers of the army in Pit 1 (the largest yet found) we see a view that no one had seen for more than two thousand years — from the time that the tombs were sealed until the excavations of the 1970s. The figures were set into paved channels of earth, reinforced with wooden planks and then buried.

The soldiers are arranged in battle formation, with a vanguard of archers surrounding the bulk of the army. The hands of the archers are now empty, but they originally held wooden bows, of which some traces survive. These wooden bows, along with bronze weapons held by other soldiers, would have given the soldiers a more naturalistic appearance.

As a whole, the layout and design of the army emphasizes pattern and repetition. The soldiers are all of very similar size — slightly larger than life — and are standing in repeated poses. They are arranged in consistent rows, which establishes a very regular pattern. It also creates a sense of unity, which is an ideal generally sought by real armies. These soldiers are clearly, through their unified appearances, collectively working to express, enforce and protect the power of the emperor, even as he lies in his grave. There is, though, variety throughout the army, enlivening the whole with small, humanizing differences in features and costume.

The scale of the project is hard to comprehend. This is not a token set of guards around the imperial tomb, but a complete army, from foot soldiers and cavalrymen to generals. To get a sense of these figures, we will look first at an archer from Pit 2. The archer wears a long robe and armor over his torso and shoulders and kneels on his right knee. He originally held a bronze crossbow, a weapon that shot heavier arrows faster and farther than bows.

His armor is quite detailed. The immensity of the labor required to produce the thousands of figures is stressed by viewing the figure from the back, revealing the attention paid even to the sole of his shoe. It bears three different patterns in the tread, to differentiate heel, center and toe. The care taken over such a minor detail emphasizes the power of the patron, and the vastness of his wealth.

Still, while there is great attention to detail, which suggests the individuality of the figures, there are also techniques used to grant the whole composition its consistent and impressive unity. The most obvious method used to create a sense of unity is the depiction of their armor: since they are an army, they are dressed in very consistent uniforms. There are, though, subtler techniques used to suggest that the figures are not actually individual portraits but slightly differentiated versions of a generalized, idealized soldier. The folds of the archer’s clothing, for example, are stylized: we know that the heavy cuts into the surface of the terracotta represent folds in heavy cloth, but they do so in a generalized way, rather than seeming like each was carefully copied from reality.

The figure’s face is also at once individualized and slightly abstracted. Its sense of individuality does not come from intense verism, from the rendering of every wrinkle and imperfection, but from the lively and alert expression. All of the features are smoothed out, made angular. Some of the figures bear bushy mustaches and beards or thick eyebrows, but this figure’s features are all more minimally presented. The halves of his mustache are flat planes, and his eyebrows are smooth ridges.

All of the artist’s efforts here seem to be focused on his watchful state. The figure, like all of the thousands at the site, is idealized. The archer appears to be youthful and strong. His face is highly symmetrical, though this is humanized by his off-center top-knot of hair. He, like all those around him, is an ideal soldier to serve in the emperor’s imposing army.

Equally impressive are the great chariots, including the war chariot. These were found just outside the actual burial of Qin Shi Huangdi (which remains unexcavated at this time). Two bronze chariots were found, one considered a war chariot and the other a peace chariot. Both chariots were found in fragments but have been restored. They are about half life-size, and intricately designed. The war chariot contains gold and silver embellishments on the canopy pole and the horses’ bridles, as well as other parts of their tack.

The horses are depicted in much the same style as the terracotta figures, with a delicate balance between naturalism and stylization. Their heads and bodies are somewhat generalized, so that we do not see veins or tendons standing out beneath the hide, for example, and yet they are still quite lively. Their ears are perked up as if with attention, their heads tossing as they bite their bits. They were originally painted white, with red tongues, which would have granted them an even more lively appearance.

The horses, like the soldiers, are each individualized, and yet clearly all part of a cohesive team. They are all of the same size, and wear similar gear, but they differ in subtleties of the nostrils and eyes, for example. A crossbow hangs within easy reach of the driver, elaborately decorated with patterns. A quiver containing 54 bronze arrows of two different types — diamond-shaped and flat tipped — was found hanging from the inside of the chariot’s rail. Once the emperor died and his dynasty was quickly disintegrating, mobs plundered the tomb and took the weapons because they could be used.

The burial of Qin Shi Huangdi reflects the worldly power of the emperor. In ancient China, very elaborate burials were standard features of imperial court practice, and were copied by lesser members of the aristocracy, as well. In the earlier Shang Dynasty (c. sixteenth-eleventh century B.C.E.), rulers were buried with lavish possessions (as well as with their servants — human sacrifices were also common in the Shang Dynasty, and continued through successive periods).

By the time that Qin Shi Huangdi commissioned his elaborate tomb, these practices were already ancient, and set the precedent for his ritual specialists to follow. Sima Qian’s Shiji (Historical Records) provides an account of the tomb (Sima Qian is considered the first major historian of China; he wrote during the Han Dynasty that succeeded the Qin). His description attests to the continued practice of human sacrifices, as well as the to great measures taken to secure the tomb against raiders seeking its riches.

He tells us:

The tomb vault was dug through three underground streams and the coffins were cast in copper. Palaces were built within the burial mound and the burial chamber itself was a rich repository full of precious and rare treasures. Artisans were commanded to contrive gadgets controlling hidden arrows so that if tomb robbers approached, they would be bound to touch the gadgets and so trigger the arrows. On the floor of the vault mercury representing the rivers and seas was kept flowing by mechanical devices. The dome of the vault was decorated with the sun, moon and stars, and the ground depicted the nine regions and five mountains of China. … At the entombment the Second Emperor decreed that it was not fitting that the childless concubines of the First Emperor should be allowed to leave the imperial palace and should all be buried with the Emperor. Thus, the number of those who died was very great.

As quoted in Zhang Wenli, The Qin Terracotta Army: Treasures of Lintong (London: Scala Books, 1996), 14-16.

Like most imperial burials in China, Qin Shi Huangdi’s burial chamber remains sealed, and so this early account of its vaults and surroundings has not yet been confirmed (though there are heavy concentrations of mercury in the soil around it, suggesting at least some accuracy).But why would an emperor wish to be buried with a terracotta army, with bronze chariots and teams of horses, and even with his concubines?

In ancient China, death was seen not as the complete end to an individual but rather, a new stage in life. Therefore, the army was intended not only to demonstrate the emperor’s power in this life, but also to extend that same power into the world of the dead.

Admittedly biased Confucian historians of later dynasties describe Qin Shi Huangdi as paranoid, though the two documented attempts on his life suggest that some fear would not have been irrational. Desiring to preserve his power eternally, he had the ideal army constructed, and placed to the east of his tomb — the direction of his enemies in life.

This massive project should be seen in the context of Qin Shi Huangdi’s other efforts, including the beginning of the Great Wall of China, built to keep out northern invaders in the world of the living. The first emperor gained unified control over China through military force, censorship of information and ideas, and a strong defense against outside forces. Having accomplished this, he then worked to ensure that he would continue to hold such worldly power — even after his death.

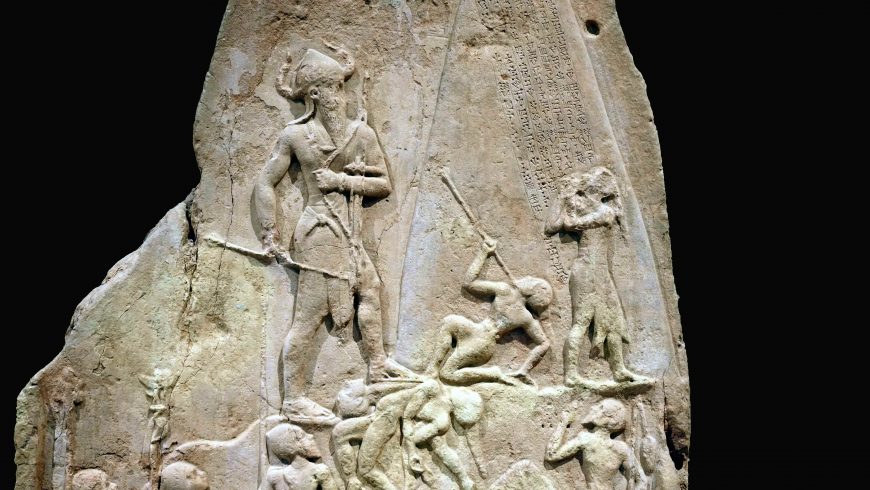

Naram-Sin guided to victory by the gods

The earliest written records to survive come from the Ancient Near East — from a series of civilizations that flourished in what are now Iran and Iraq. One of the period’s earliest empires — the Akkadian empire — was established by Naram-Sin, who inherited the throne and ruled until 2218 B.C.E.

Naram-Sin’s grandfather, Sargon I, was purportedly the illegitimate son of a high priestess and sent down the Euphrates river in a basket (much like Moses — this is a common trope in ancient myth) before being rescued and raised by a gardener. He founded a city and established dominance in the region through military success. Naram-Sin continued in his grandfather’s path, gaining power through force, and extending Akkad’s range of control and influence. In order to maintain this control, though, Naram-Sin had to frequently crush rebellions.

The Victory Stele of Naram-Sin commemorates his defeat of the Lullubi. The stele makes a strong visual statement about the power of Naram-Sin. The composition is arranged in loose registers, angling up from the lower left to the upper right. The main figure is easy to spot, here: Naram-Sin is represented in hieratic scale, so that he towers over all the figures around him. He is the highest figure on this large stele (which is over six and a half feet tall). He is also surrounded by more negative space than the other figures, who in contrast are crowded together in a jumble.

The space around the king is empty, so that he stands out clearly. This, though, merely draws our attention to him. His power is shown through his actions and the symbols on and around him.

Just in front of him, a figure clutches a spear that Naram-Sin has thrust through his neck. The king carries other spears, a bow and arrows, and a battle-axe, as if a one-man army. Unlike Qin Shi Huangdi, who demonstrated his military power through images of his thousands of soldiers, Naram-Sin had himself presented as the most powerful member of his army, displaying a god-like ability to slaughter his enemies.

In addition to the dying figure bending backward before him, there are two more corpses splayed out in a heap beneath his left foot. Another falls vertically down the stele, breaking through the registers. Additional figures raise their hands to plead for their lives even as they flee — note how the torso and face of the pleading figure in front of Naram-Sin is facing the conquering king, while his feet clearly point in the opposite direction.

The massive and aggressive figure of Naram-Sin is capped with a horned helmet, an attribute that prior to this image was only depicted on gods and that therefore suggests that he has been deified (considered as a god). Inscriptions tell us that he was known by the title “god of Akkad,” and here the power of this mighty god-king seems infinite. As he ascends the mountain, he moves closer to the three suns (one now mostly lost) at the apex of the image. These are symbols of the gods of the Akkadians, guiding Naram-Sin to victory and suggesting his own divinity.

Victory Stele of Naram-Sin

Great Pyramids of Giza and the Great Sphinx

Representations of power in the ancient world reached their peak with the art and architecture of the Egyptian pharaohs, particularly in the Great Pyramids of Giza. Built by the pharaohs Menkaure, Khafre and Khufu, they remain the most monumental works of architecture in the world — no more massive buildings have ever been built. These are the only surviving works of the so-called Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, a group of marvels described in Ancient Greece to acknowledge what were considered to be the most remarkable works of art and architecture known at the time, and their survival is due to their massive style of construction.

As the focal points within a necropolis, they dominate the landscape. The Pyramid of Khufu is the oldest and largest. It was originally nearly 500 feet tall at the apex, and the base is approximately 750 feet long on each side, covering thirteen acres.

The size of the pyramids is not all that conveys the power of their patrons; the style also impacts this impression. They are not only large, and radially symmetrical, but also almost completely unadorned. Originally, the surfaces were covered with smooth blocks that would have given them perfectly straight sides, rather than the stepped sides they now have. They would therefore have presented the viewer with a structure so unified that each might even seem to be a single object on the grandest possible scale. While Qin Shi Huangdi was also buried beneath a mound, his low hill was carefully concealed from view beneath grass and trees. In strong contrast, these works are literally man-made mountains, rising over the flat planes of Giza, dominating the landscape and dwarfing all surrounding structures. As such, they were very clear statements of the power of the god-kings buried within them.

The pharaohs commissioned numerous images of themselves, many of which were created for spaces inside and around the pyramids. Perhaps most well-known of these is the Great Sphinx, guarding the entrance to the Pyramid of Khafre. It sits at the entrance to the long causeway that leads to a funerary temple and then to the pyramid. This figure, 65 feet tall and almost 190 feet in length, has the body of a lion but is capped by an image of the head of the pharaoh, wearing the royal cobra headdress.

The Sphinx sits upright and alert, in formal symmetry. The figure was not assembled out of blocks, as the pyramids were, but rather, was carved out of “living rock” — stone still connected to the earth — though there are some additions to this. The image suggests the pharaoh’s tremendous power, since it is not only colossal but also merges him with the most respected predator of Africa: the lion. The Sphinx has unusually large eyes, and this emphasis serves to suggest that this powerful creature is a most watchful guardian. Qin Shi Huangdi entrusted his protection in the afterlife to his vigilant soldiers. Khafre, on the other hand, seems to guard himself.

Augustus of Primaporta

Today, politicians think very carefully about how they will be photographed. Think about all the campaign commercials and print ads we are bombarded with every election season. These images tell us a lot about the candidate, including what they stand for and what agendas they are promoting. Similarly, Roman art was closely intertwined with politics and propaganda. This is especially true with portraits of Augustus, the first emperor of the Roman Empire; Augustus invoked the power of imagery to communicate his ideology.

One of Augustus’ most famous portraits is the so-called Augustus of Primaporta of 20 B.C.E. (the sculpture gets its name from the town in Italy where it was found in 1863). At first glance this statue might appear to simply resemble a portrait of Augustus as an orator and general, but this sculpture also communicates a good deal about the emperor’s power and ideology. In fact, in this portrait Augustus shows himself as a great military victor and a staunch supporter of Roman religion. The statue also foretells the 200-year period of peace that Augustus initiated, called the Pax Romana.

In this marble freestanding sculpture, Augustus stands in a contrapposto pose. The emperor wears military regalia and his right arm is outstretched, demonstrating that the emperor is addressing his troops. We immediately sense the emperor’s power as the leader of the army and a military conqueror.

Delving further into the composition of the Primaporta statue, a distinct resemblance to Polykleitos’ Doryphoros, a Classical Greek sculpture of the fifth century B.C.E., is apparent. Both have a similar contrapposto stance, and both are idealized. That is to say that both Augustus and the Spear-Bearer are portrayed as youthful and flawless individuals: they are perfect. The Romans often modeled their art on Greek predecessors. This is significant because Augustus is essentially depicting himself with the perfect body of a Greek athlete: he is youthful and virile, despite the fact that he was middle-aged at the time of the sculpture’s commissioning. Furthermore, by modeling the Primaporta statue on such an iconic Greek sculpture created during the height of Athens’ influence and power, Augustus connects himself to the Golden Age of that previous civilization.

So far, the message of the Augustus of Primaporta is clear: he is an excellent orator and military victor with the youthful and perfect body of a Greek athlete. Is that all there is to this sculpture? Definitely not! The sculpture contains even more symbolism. First, at Augustus’ right leg is cupid figure riding a dolphin.

The dolphin became a symbol of Augustus’ great naval victory over Mark Antony and Cleopatra at the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, a conquest that made Augustus the sole ruler of the Empire. The cupid astride the dolphin sends another message too: that Augustus is descended from the gods. Cupid is the son of Venus, the Roman goddess of love. Julius Caesar, the adoptive father of Augustus, claimed to be descended from Venus and therefore Augustus also shared this connection to the gods.

Finally, Augustus is wearing a cuirass that is covered with figures that communicate additional propagandistic messages. Scholars debate over the identification over each of these figures, but the basic meaning is clear: Augustus has the gods on his side, he is an international military victor, and he is the bringer of the Pax Romana, a peace that encompasses all the lands of the Roman Empire. In the central zone of the cuirass are two figures, a Roman and a Parthian. On the right, the enemy Parthian returns military standards. This is a direct reference to an international diplomatic victory of Augustus in 20 B.C.E., when these standards were finally returned to Rome after a previous battle.

Surrounding this central zone are gods and personifications. At the top are Sol and Caelus, the sun and sky gods respectively. On the sides of the breastplate are female personifications of countries conquered by Augustus. These gods and personifications refer to the Pax Romana. The message is that the sun is going to shine on all regions of the Roman Empire, bringing peace and prosperity to all citizens. And of course, Augustus is the one who is responsible for this abundance throughout the Empire. Beneath the female personifications are Apollo and Diana, two major deities in the Roman pantheon; clearly Augustus is favored by these important deities and their appearance here demonstrates that the emperor supports traditional Roman religion. At the very bottom of the cuirass is Tellus, the earth goddess, who cradles two babies and holds a cornucopia. Tellus is an additional allusion to the Pax Romana as she is a symbol of fertility with her healthy babies and overflowing horn of plenty.

The Augustus of Primaporta is one of the ways that the ancients used art for propagandistic purposes. Overall, this statue is not simply a portrait of the emperor, it expresses Augustus’ connection to the past, his role as a military victor, his connection to the gods, and his role as the bringer of the Roman Peace.

Augustus of Primaporta, power and propaganda

A staff for a Benin king

Here, we see a rattle staff, called an ukhurhe, made for a powerful oba, or king. Oba Akenzua I ruled Benin in the early eighteenth century. The oba’s staff is capped with an image of himself, holding a simpler ukhurhe. This staff was probably used as a public political statement of power, unlike more traditional ukhurhe, which were carved in wood.

Akenzua’s great, wide-set eyes would have been directed both at his ancestors — the source of his power and authority — and at his subjects. The staff, over five feet tall, has a hollow segment near the top, with narrow slits along its length, which rattles when shaken during prayers. This example is brass, which means it was a high-status item. As with Qin Shi Huangdi, there is a balance in this work between worldly and spiritual power. The oba is shown dressed for a ceremony in elaborate royal garb, much of which would be made of valuable materials. As shown on the image on the ukhurhe, his headdress, the rings around his neck, and the panels on his chest would be made of coral and his armbands would be of ivory. This costly costume would declare to the viewer that the figure is no ordinary man[1].

These large, watchful eyes can be found in thousands of images of gods and rulers, giving the viewer the sense that these absent individuals are nonetheless scrutinizing us. The portrait style common in the art of the Benin kingdom of the eighteenth century is highly abstract, with features of importance enlarged for emphasis. In this way, proportion is manipulated to draw the viewer’s attention to key elements, like the eyes.

The figure’s importance is declared by his placement at the top of this luxury item, and his symmetry gives him a stable, solid, dignified appearance. His enlarged eyes declare his watchful nature. While the image of Akenzua itself is small — only about six inches in height — hieratic scale is used to demonstrate his importance: he stands on the back of an elephant, an animal associated with rulership, and is more than twice its height. The elephant’s trunk ends in a human hand. This may be a reference to Iyase n’Ode, believed to be able to transform into an elephant, who led a rebellion against Akenzua.

Placing Akenzua atop the elephant makes a strong statement about Iyase n’Ode’s defeat and the oba’s triumph. The elephant is also hemmed in on both sides by leopards, symbols of the oba’s power. The elaborate nature of the depiction of the oba is the result of the centrality of the king to the art of Benin.

The oba was both the main subject of the art, and also its most important patron. This forceful depiction of Akenzua’s power is fitting, as he was the ruler of a kingdom that had ruled the region since the fifteenth century. In this case, therefore, the iconography — the series of signs and symbols in the art of a culture — works with the principles of composition to create a strong statement of the oba’s authority.

Napoleon on his throne

We again confront the direct gaze of the ruler when we stand before Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres’s large oil painting Napoleon on his Imperial Throne. This is a work that tries very hard to capture some of the majesty of earlier images of rulers through composition, technique and symbolism.

The recently crowned emperor is shown centered in a highly symmetrical composition, seated on a gilded throne that frames his head like a halo, suggesting his divinity. The semi-circle of the white ermine fur cape draped over his shoulders visually completes the semi-circle of the back of the throne. The circles are carefully aligned to seem to be continuations of one another, thereby doubly framing Napoleon’s head.

Napoleon’s clothing and accessories could not be more sumptuous: fur, velvet in red — the color that has symbolized imperial power since Ancient Rome — and gold. The staff he holds in his right hand is topped with an image of Charlemagne, the revered medieval French king who was the first to be crowned emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. This great predecessor (Charlemagne is French for “Charles the Great”) is posed quite similarly to Napoleon, suggesting a strong connection between these two French rulers, each of whom was the first in his era to be declared emperor.

Like the image of Akenzua on his ukhurhe, holding an ukhurhe, here the small image of Charlemagne atop Napoleon’s staff also holds in his right hand a staff — this one capped with the fleur-de-lis (the symbol of the French monarchy).

The staff in Napoleon’s left hand was believed at the time to have belonged to Charlemagne, and the sword he bears is that of his precursor, as well. As Qin Shi Huangdi used ancient burial practices to connect himself to the tradition of his ancestors, Napoleon used these medieval treasures to connect himself with the past of France. He also bears the golden laurel wreath crown of the Roman emperors, and the arms of his golden throne and the carpet at his feet both contain the image of the Roman eagle.

Ingres paints all of these elements with extreme precision, so that we can see each gem and jewel, and with such attention to the texture of the materials that is seems almost as if we could feel them beneath our fingers, as we look at the image. This lavish portrait was an attempt by Napoleon to demonstrate his great power, and also to argue that, although he had created a new empire, he was continuing the tradition of Charlemagne, and of the great Roman emperors of antiquity.

Appropriating symbols of power

For a more recent example, we turn to a statue of Saddam Hussein, former dictator of Iraq, which once stood in Firdos Square, Baghdad. This statue was one of thousands of images of Hussein and was produced (as many of the images in this chapter were), at the orders of a powerful patron. It was a monumental bronze sculpture, set on a tall pedestal. Hussein appeared in a business suit, with a hand raised as if he were greeting a large crowd of supporters.

This image became famous throughout the world just a month after the United States-led invasion of Iraq began, and serves as a reminder that symbols of power can be used against those they are created to glorify. On April 9, 2003, a battalion of US marines secured central Baghdad and arrived in Firdos Square, in front of the Palestine Hotel, where over two hundred reporters were staying. The presence of so many reporters meant that, as the Marines assisted a group of Iraqis in toppling the statue, the event was broadcast live throughout the world.

The statue celebrated and declared Hussein’s power, but in the aftermath of the invasion, its toppling became a more complicated symbol of his fall from power. According to the most detailed account available, a US marine instigated the small crowd of Iraqis, and provided them a sledgehammer and rope. When it was clear this was not sufficient to pull down the statue, the marines sought and received authorization to use a large tow truck to topple it. While a corporal was hooking up a chain to the statue’s head, he was handed a U.S. flag, which the wind then whipped across the face of the image of Hussein. He spread it more fully across the face and, seconds later, took it down.

This brief moment was photographed, filmed, and broadcast, becoming a central image of the invasion. Had the Iraqis pulled down the statue without the help of the truck, images would have appeared to show a spontaneous act by a joyously liberated populace (though this would have been false). Had the statue been toppled without the flag, the images would appear to show cooperation between the Iraqi people and the US military. The ultimate image (though it was not really such) looked like a deliberate statement by a conquering occupier. In this way, a work of propaganda for a powerful, autocratic ruler became a symbol of his defeat at the hands of an invading military.

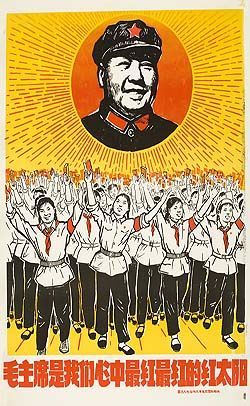

Art for the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution

In 1966, the Chinese Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong began the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. The movement was intended to address growing class inequality. When the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949, one of its founders’ goals was to decrease the economic divide between the rich and poor, but in the following decades, as Mao saw it, the government had moved away from this principle.

In the propaganda poster Chairman Mao is the reddest red sun in our hearts, we see Chairman Mao in the center of the red sun, smiling and radiant. Beneath him is an army of loyal supporters. These figures stand in for the 20 million youths who joined the Red Guard in order to root out “class enemies.” They hold aloft copies of Mao’s Little Red Book, which contains a list of sayings to encourage the masses to fight against class oppression. For example:

In class society, everyone lives as a member of a particular class, and every kind of thinking, without exception, is stamped with the brand of a class. It is up to us to organize the people. As for the reactionaries in China, it is up to us to organize the people to overthrow them. Everything reactionary is the same; if you do not hit it, it will not fall. This is also like sweeping the floor; as a rule, where the broom does not reach, the dust will not vanish of itself.

Mao Zedong, LITTLE RED BOOK, 1964

Like most propaganda, it is not intended to be subtle; it is supposed to make a clear and dramatic point. The placement of Mao, centered at the top of the image, declares his importance, which is reinforced by the seemingly infinite crowd beneath him. Like the soldiers of Qin Shi Huangdi, they are nearly identical in dress, conveying their common purpose, but are slightly differentiated to give a sense of the individuality of the volunteers, united behind Mao.

The horizon line is located behind the figures, approximately at the eye-level of the young women in the front row. This effectively places the viewer within the crowd, as if we are marching along with them. It also has the effect, as the figures recede into the distance, of dissolving the crowd into a sea of hands, all holding up the Little Red Book toward the giant image of Mao. As the raised hands of the figures recede into the distance, the amount of detail diminishes, so the books they hold lose their black outlines. The effect of this is to make them seem as if they are being formed out of the rays that emanate from the red circle around Mao. Like a sun god, Mao shines his message down onto his followers, who receive it with great joy.

The woodcut technique used here — in which a series of blocks is carved to create the image, covered with ink, and then pressed to the page — has become a staple of political imagery since the 1960s. It is an inexpensive way of producing a large number of images. Unlike the impressive and expensive works discussed above, this poster achieved its effect through large-scale distribution. The high contrast and large, flat panels of color common in woodcuts make this technique well suited to carrying clear messages to the masses.

- In a photograph of his descendant, Akenzua II (who ruled from 1933-1978), we can see an oba in a similar costume, giving a sense of how Akenzua I would have appeared in life. ↵

an upright stone slab or column typically bearing a commemorative inscription or relief design

A visual method of marking the significance of a figure through its size. The more important a figure is, the larger it appears.

a piece of armor consisting of breastplate and backplate fastened together