9 Empires of the East: Art of Ancient China

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Trace the development of art in China through a series of empires and the introduction of Buddhism.

Looking Forward

Much of China, a country slightly larger than the continental United States, is hilly or mountainous. To its east lies the Pacific Ocean, to its south thick jungles. Mountains in the southwest connect in the west with the Himalayas, which merge with other mountains and the Taklamakan and Gobi deserts in the northwest. In the north there are frigid steppes. Internal travel is easiest along river valleys, most of which run west to east; these valleys hold most of the population. Travel north and south between them is difficult, resulting in limited contact that has contributed to the development of more than fifty minority groups, speaking dozens of local dialects, held together by a shared character-based written language.

Despite these physical barriers, China developed ties with the rest of the world through conquest, religion, and trade. Many products and technologies that were first developed in China—silk, porcelain, gunpowder, tea, paper, and woodblock printing—were much sought after by cultures far beyond its borders. In exchange the Chinese sought exotic goods, horses, and jade, as well as access to the sources of Buddhism.

Chinese art has arguably the oldest continuous tradition in the world, marked by an unusual degree of continuity within and consciousness of that tradition. This is a departure from the Western collapse and gradual recovery of classical styles. The decorative arts are extremely important in China, and much of the finest work was produced in large workshops or factories by essentially unknown artists. Much of the best work in ceramics, textiles, and other techniques was produced over a long period by the various Imperial factories or workshops, which was used by the court as well as distributed internally and abroad on a massive scale to demonstrate the wealth and power of the Emperors. In contrast, ink wash painting developed aesthetic values depending on the imagination of the artist, similar to and predating the art traditions of the West.

China in Antiquity: Shang – Han Dynasties

We will refer to Ancient China as the time between the Neolithic period (ca. 6,000 ‒ 1750 B.C.E.) and the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E.‒220 C.E.), which is roughly equivalent to the period of the Roman Empire in the West. This is the formative stage of Chinese civilization. During this time, what we now call China developed from a collection of isolated cultural communities to a set of organized states which eventually coalesced around the idea of a single unified state, and then expanded to include contact with other civilizations.

The Shang Dynasty

The Shang is the earliest dynasty in Chinese history that can be verified through written and archaeological evidence. Established around 1600 B.C.E., it was centered in north China along the Yellow River valley, the so-called cradle of Chinese civilization. This area was ruled by one centralized government—the Shang royal family. The Shang kings ruled the kingdom from the capital city, which moved many times before finally settling near the modern city of Anyang where they stayed from about 1300 B.C.E. to 1050 B.C.E. The dynasty was ultimately overthrown by the Zhou people. It is clear from archaeological findings that the Shang rulers established a stable social order. Like many other societies, they did so through religion and shared ritual practices.

One of the important factors in determining the history of the Shang is the presence of written records. Writing at this time was mostly pictographic, meaning that a word was represented by a picture that closely resembled its meaning. Over time, this writing would become more ideographic. During the Shang, there were scribes who recorded important events. What has survived are inscriptions on bronzes, and more importantly, inscriptions on oracle bones used by the Shang for divination. Thousands of bones have been recovered, many of them broken.

The term “oracle bone” refers to ox scapulae (shoulder blade bones) and tortoise plastrons (bottom, flat part of the shell) used by Shang rulers for divination. Oracle bones were said to offer a conduit to the spirits of royal ancestors, legendary figures from the past, nature deities, and other powerful spirits. Shang kings asked about natural events, illnesses, dreams, and forecasts for hunting and military endeavors.

Under the direction of the king and his diviner, the bones of cattle and water buffalo and the shells of tortoises were scraped clean, polished, and perhaps soaked. When dry, the bones or shells were chiseled to produce rows of grooves and pits. During the ritual, a diviner would insert a heated rod into the bottom of the grooves and pits to produce hairline cracks on the opposite side of the bone or shell. The diviner requested information and guidance from the spirit of a royal ancestor and then interpreted the direction of the cracks to provide answers to the king’s question. To record the king’s question, a scribe would then carve it onto the bone or shell surface relative to the cracks.

Later, the scribe would carve the outcome onto the surface of the bones or shells. The tortoise shell fragment from the collection of the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, for instance, has three groups of finely engraved inscriptions. Two of them relate to the question of rain; the third reports on the outcome of a successful deer hunt. Most oracle bone inscriptions contain four parts: an introduction, a charge (the topic of the oracle-bone inscription), the prognostication (interpretation of cracks), and verification (the actual outcome of the oracle bone inscription topic).

Oracle Bone, Shang Dynasty

The king would also make frequent sacrifices to ancestors to ensure their happiness so that they would continue to protect and bless his family and people. This began the enduring tradition of ancestor worship in Chinese culture. Bronze vessels played a critical role in these religious rituals. They were used to present offerings of wine and food to ancestral spirits. Wine vessels were particularly important for the Shang people, considering the number and variety of wine vessels discovered in Shang tombs. Some of the bronze vessels bear short inscriptions, usually two or three characters long, referring to a clan name and deceased ancestor. The Shang people’s love for animal designs is demonstrated by the common motifs used for Shang ritual bronzes, which included taotie masks, dragons, birds, and other geometric patterns. Besides vessels, bronze was used to make weapons for warfare. Together with chariots that had bronze fittings, these weapons equipped the Shang military force and allowed the Shang to maintain its military supremacy. However, the primary function for bronze was probably to make tools that increased the efficiency of agriculture and food production.

Tigers, Dragons, and Monsters on a Shang Dynasty Ewer

Jade was worn by kings and nobles and after death placed with them in the tomb. As a result, the material became associated with royalty and high status. It also came to be regarded as powerful in death, protecting the body from decay. In later times these magical properties were perhaps less explicitly recognized, jade being valued more for its use in exquisite ornaments and vessels, and for its links with antiquity. In the Ming and Qing periods ancient jade shapes and decorative patterns were often copied, thereby bringing the associations of the distant past to the Chinese peoples of later times.

Jade[1] has always been the material most highly prized by the Chinese, above silver and gold. From ancient times, this extremely tough translucent stone has been worked into ornaments, ceremonial weapons and ritual objects. Recent archaeological finds in many parts of China have revealed not only the antiquity of the skill of jade carving, but also the extraordinary levels of development it achieved at a very early date.

Jade continued to be highly prized during the Shang dynasty. Some types of jade objects first created in the Neolithic period (c. 7000–1700 B.C.E.), such as the bi (a circular disk with a hole that represented the sky) and cong (a vessel that’s square on the outside but circular on the inside and represented the earth), were still produced for ceremonial purposes. Since bronze was acquiring new importance as the material for conducting rituals, however, jade was more commonly used for personal ornaments.

The Qin Dynasty

At the end of the Warring States period (475–221 B.C.E.), the state of Qin conquered all other states and established the Qin dynasty (221–206 B.C.E.). It was China’s first unified state whose power was centralized instead of spread among different kingdoms in the north and south. Although it lasted only about fifteen years, the Qin dynasty greatly influenced the next two thousand years of Chinese history.

The first emperor of Qin, known as Qin Shihuangdi (literally “First Emperor,” 259–210 B.C.E.), instituted a central and systematic bureaucracy. He divided the state into provinces and prefectures governed by appointed officials. This administrative structure has served as a model for government in China to the present day. Shihuangdi sought to standardize numerous aspects of Chinese life, including weights and measures, coinage, and the writing system. These standards would last for centuries after the fall of his short-lived dynasty. He also ordered many construction projects. He expanded the network of roads and canals throughout the country. The first Great Wall (not the one that exists today) was built during his reign.

Despite the many accomplishments of the Qin dynasty, Shihuangdi was considered a severe ruler. He was intolerant of any threats to his rule and established harsh laws to maintain his control. He had his chief advisor burn all books that were not written on subjects he considered useful (useful subjects included agriculture and medicine) and reportedly buried hundreds of scholars alive.

During its reign over China, the Qin Dynasty achieved increased trade, improved agriculture, and revolutionary developments in military tactics, transportation, and weaponry. Qin Shihuang, the self-proclaimed first Emperor of the Qin Dynasty, made vast improvements to the military, which used the most advanced weaponry of its time.

Despite its military strength, however, the Dynasty did not last long. When Qin Shihuang died in 210 BCE, his son was placed on the throne by two of the previous emperor’s advisers, who attempted to influence and control the administration of the entire dynasty through him. The advisers fought among themselves, however, which resulted in both their deaths and that of the second Qin emperor. Popular revolt broke out a few years later, and the weakened empire soon fell to a Chu lieutenant, who went on to found the Han Dynasty. Despite its rapid end, the Qin Dynasty influenced future Chinese empires, particularly the Han, and the European name for China is thought to be derived from it.

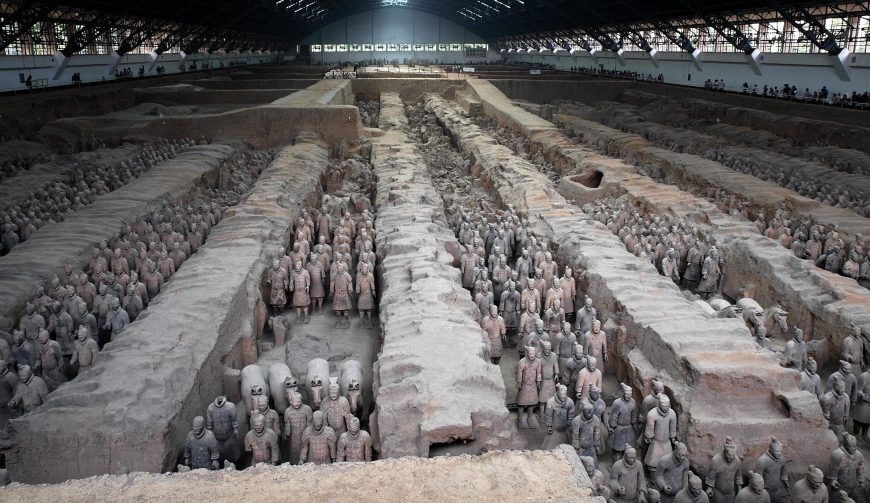

The Qin dynasty is one of the best-known periods in Chinese history in the West because of the 1974 discovery of thousands of life-size terracotta warriors intended to protect the emperor after his death. The Terracotta Army was inconspicuous due to its underground location and thus not discovered until 1974. The “army” of sculptures consists of more than 7,000 life-size terracotta figures of warriors and horses that were buried with Qin Shihuang after his death in 210–209 BCE. The three pits containing the Terracotta Army were estimated in 2007 to hold more than 8,000 soldiers, 130 chariots with 520 horses, and 150 cavalry horses, the majority of which remained buried in the pits nearby Qin Shi Huang’s mausoleum. Non-military terracotta figures were found in other pits, including officials, acrobats, strongmen, and musicians.

The figures were painted in bright pigments before they were placed in the vault, and the original colors of pink, red, green, blue, black, brown, white, and lilac were visible when the pieces were first unearthed. However, exposure to air has caused the pigments to fade and flake off, revealing their natural terracotta color. The figures were constructed in several poses, including standing infantry, kneeling archers, and charioteers with horses. They vary in height according to their roles, with the generals tallest, and each figure’s head appears to be unique, with a variety of facial features, expressions, and hair styles. Along with the colored lacquer finish, the individual facial features would have given the figures a realistic feel.

The terracotta army figures were manufactured in workshops by government laborers and local craftsmen using local materials. Heads, arms, legs, and torsos were created separately and then assembled. Eight face molds were most likely used, with clay added after assembly to provide individual facial features. It is believed that the legs were made using the same process used for terracotta drainage pipes. This would classify the process as assembly line production, with specific parts manufactured and assembled after being fired, as opposed to being crafted from one solid piece and subsequently fired. In those times of tight imperial control, each workshop was required to inscribe its name on items produced to ensure quality control.

Han China

The Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 C.E.) reunified China after the civil war following the death of Qin Shihuangdi in 210 B.C.E. It is divided into two periods: the Former (or Western) Han, when Chang’an (present-day Xi’an) was its capital; and the Later (or Eastern) Han, which ruled from Luoyang—230 miles east of Xi’an. The Han dynasty was a pivotal period in the history of China. During its long reign of almost four hundred years, many foundations were laid for enduring aspects of Chinese society.

Philosophy and literature flourished during the Han dynasty. Confucianism became the official government orthodoxy. A civil service was created with entrance examinations based on knowledge of Confucian texts—a system that lasted through the early twentieth century. Daoism continued to grow in influence, however, and Buddhism was introduced from India via the Silk Road.

During the rule of Emperor Wu (reigned 141–87 B.C.E.), the Han defeated the Xiongnu, a Central Asian nomadic tribal group that resided west of China proper and gained control of the regions where the Xiongnu lived. China was now in control of the trading routes across the middle of Asia for the first time. These routes extended to the Mediterranean region and the Near East and were later known as the Silk Road. People that lived along the Silk Road exchanged various goods, as well as ideas, religions, and technologies.

Bronzes and jades in the Han dynasty became even more closely associated with affluence and luxury than in any previous dynasty. In contrast to their use in religious rituals during the Shang dynasty, these items were now made for grand festivities and display. One special and well-known type of jade object crafted by the Han people was the luxurious jade burial suit, as jade was believed to have preserving power. At the same time, increased contact with India, Persia, and other countries along the Silk Road introduced new symbols, motifs, and techniques to Chinese art.

The elite men and women of the Han dynasty enjoyed an opulent lifestyle that could stretch into the afterlife. Today, the well-furnished tombs of the elite give us a glimpse of the luxurious goods they treasured and enjoyed. For instance, a wealthy official could afford beautiful silk robes in contrast to the homespun or paper garments of a laborer or peasant. Their tombs also inform us about their cosmological beliefs.

Architecture for the Dead: Watchtower (Eastern Han Dynasty)

Three elite tombs, discovered in 1972, at Mawangdui, Hunan Province (eastern China) rank amongst the greatest archeological discoveries in China during the 20th century. They are the tombs of a high-ranking Han official civil servant, the Marquis of Dai, Lady Dai (his wife), and their son. The Marquis died in 186 B.C.E., and his wife and son both died by 163 B.C.E. The Marquis’ tomb was not in good condition when it was discovered. However, the objects in the son’s and wife’s tombs were of extraordinary quality and very well preserved. From these objects, we can see that Lady Dai and her son were to spend the afterlife in sumptuous comfort.

In Lady Dai’s tomb, archaeologists found a painted silk banner over six feet long in excellent condition. The T-shaped banner was on top of the innermost of four nesting coffins. Although scholars still debate the function of these banners, we know they had some connection with the afterlife. They may be “name banners” used to identify the dead during the mourning ceremonies, or they may have been burial shrouds intended to aid the soul in its passage to the afterlife. Lady Dai’s banner is important for two primary reasons. It is an early example of pictorial (representing naturalistic scenes not just abstract shapes) art in China. Secondly, the banner features the earliest known portrait in Chinese painting.

We can divide Lady Dai’s banner into four horizontal registers. In the lower central register, we see Lady Dai in an embroidered silk robe leaning on a staff. This remarkable portrait of Lady Dai is the earliest example of a painted portrait of a specific individual in China. She stands on a platform along with her servants–two in front and three behind.

Long, sinuous dragons frame the scene on either side, and their white and pink bodies loop through a bi (a disc with a hole thought to represent the sky) underneath Lady Dai. We understand that this is not a portrait of Lady Dai in her former life, but an image of her in the afterlife enjoying the immortal comforts of her tomb as she ascends toward the heavens.

In the register below the scene of Lady Dai, we see sacrificial funerary rituals taking place in a mourning hall. Tripod containers and vase-shaped vessels for offering food and wine stand in the foreground. In the middle ground, seated mourners line up in two rows. Look for the mound in the center, between the two rows of mourners. If you look closely, you can see the patterns on the silk that match the robe Lady Dai wears in the scene above. Her corpse is wrapped in her finest robe! More vessels appear on a shelf in the background.

In the mourning scene, we can also appreciate the importance of Lady Dai’s banner for understanding how artists began to represent depth and space in early Chinese painting. They made efforts to indicate depth through the use of the overlapping bodies of the mourners. They also made objects in the foreground larger, and objects in the background smaller, to create the illusion of space in the mourning hall.

Lady Dai’s banner gives us some insight into cosmological beliefs and funeral practices of Han dynasty China. Above and below the scenes of Lady Dai and the mourning hall, we see images of heaven and the underworld. Toward the top, near the cross of the “T,” two men face each other and guard the gate to the heavenly realm. Directly above the two men, at the very top of the banner, we see a deity with a human head and a dragon body.

On the left, a toad standing on a crescent moon flanks the dragon/human deity. On the right, we see what may be a three-legged crow within a pink sun. The moon and the sun are emblematic of a supernatural realm above the human world. Dragons and other immortal beings populate the sky. In the lower register, beneath the mourning hall, we see the underworld populated by two giant black fish, a red snake, a pair of blue goats, and an unidentified earthly deity. The deity appears to hold up the floor of the mourning hall, while the two fish cross to form a circle beneath him. The beings in the underworld symbolize water and earth, and they indicate an underground domain below the human world.

Medieval China: Tang and Song Dynasties

Scholars often refer to the Tang (618–906) and Song (960–1279) dynasties as the “medieval” period of China. The civilizations of the Tang (618–906) and Song (960–1279) dynasties of China were among the most advanced civilizations in the world at the time. Discoveries in the realms of science, art, philosophy, and technology—combined with a curiosity about the world around them—provided the men and women of this period with a worldview and level of sophistication that in many ways were unrivaled until much later times, even in China itself.

The Tang Dynasty

When the rulers of the Tang dynasty (618–906) unified China in the early seventh century, the energies and wealth of the nation proved strong enough not only to ensure internal peace for the first time in centuries, but also to expand the Chinese realm to include large portions of neighboring lands such as Korea, Vietnam, northeast, central, and southeast Asia. The Tang became a great empire, the most powerful and influential of its time any place in the world. Flourishing trade and communication transformed China into the cultural center of an international age. Tang cities such as the capital of Chang’an (modern Xi’an), the eastern terminus of the great Silk Road, were global hubs of banking and trade as well as of religious, scholarly, and artistic life. Their inhabitants, from all parts of China and as far away as India and Persia, were urbane and sophisticated.

Tang society was liberal and largely tolerant of foreign views and ideas; in fact, the royal family of Tang, surnamed Li, was of non-Han Chinese origin (perhaps originally from a Turkish-speaking area of Central Asia), and leaders of government were drawn from many parts of the region. Government was powerful, but not oppressive; education was encouraged, with the accomplished and learned well rewarded. Great wealth was accumulated by a few, but the Tang rulers saw that lands were redistributed, and all had some measure of opportunity for material advancement. This was also a time when many women attained higher status at court, and a greater degree of freedom in society.

This dynamic, affluent, liberal, and culturally diverse environment produced a great efflorescence of culture unparalleled in Chinese history. Buddhism, originally imported from India, thrived to such an extent that China itself became a major center of Buddhist learning, attracting students and pilgrims from other countries.

In East Asia, Chinese, rather than Sanskrit, became the language of Chinese Buddhist texts that served to transmit Chinese culture, ideas, and philosophy abroad. Significantly, Buddhist influence also resulted in the compilation of huge encyclopedias of knowledge during the Tang, preserving much earlier Chinese cultural material for posterity, and inspiring advances in mathematics and the applied sciences such as engineering and medicine. The Tang was also an age of great figure painters, whose religious frescoes filled caves along the Silk Road through central Asia and covered the walls of royal tombs. New styles of ceramics, bold and colorful with variegated glazes, embraced Indian, Persian, and Greek forms.

Graceful Gestures and Terrifying Guardians: Tang Tomb Figures

Buddhism probably arrived in China during the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E. – 220 C.E.) and became a central feature of Chinese culture during the period of division that followed. Buddhist teaching ascribed great merit to the reproduction of images of Buddhas and bodhisattvas, in which the artisans had to follow strict rules of iconography.

A twelfth-century catalogue of the Chinese imperial painting collection lists Daoist and Buddhist works from the time of Gu Kaizhi (c. 344-406 C.E.) onwards. However, no paintings by major artists of this period have survived, because foreign religions were proscribed between 842 and 845, and many Buddhist monuments and works of art were destroyed.

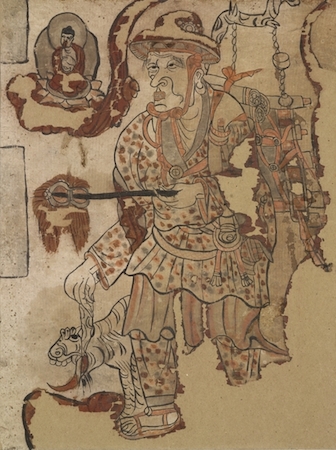

What has survived from the Tang period (618-906) is an important collection of Buddhist paintings on silk and paper, found in Cave 17, in the Valley of the Thousand Buddhas at the Chinese end of the Silk Road. Since Dunhuang was under Tibetan occupation at this time, its cave shrines and paintings escaped destruction.

The ‘Caves of the Thousand Buddhas’ (Qianfodong), also known as Mogao, are a magnificent treasure trove of Buddhist art located in the desert, about 15 miles south-east of the town of Dunhuang in northwestern China. By the late fourth century, the area had become a busy desert crossroads on the caravan routes of the Silk Road linking China and the West. Traders, pilgrims, and other travelers stopped at the oasis town to secure provisions, pray for the journey ahead or give thanks for their survival. Records state that in 366 monks carved the first caves into the cliff stretching about 1 mile along the Daquan River.

Over the next millennium more than 1000 caves of varying sizes were dug. Around five hundred of these were decorated as cave temples, carved from the gravel conglomerate of the escarpment. This material was not suitable for sculpture, as at other famous Buddhist cave temples at Yungang and Longmen.

There are about 492 extant cave-temples ranging in date from the fifth to the thirteenth centuries. During the thousand years of artistic activity at Mogao, the style of the wall paintings and sculptures changed, in part a reflection of the influences that reached it along the Silk Road. The early caves show greater Indian and Western influence, while during the Tang dynasty (618-906) the influence of the latest Chinese painting styles of the imperial court is evident. During the tenth century, Dunhuang became more isolated, and the organization of a local painting academy led to mass production of paintings with a unique style.

The cave-temples are all human-made, and the decoration of each appears to have been conceived and executed as a conceptual whole. The wall-paintings were done in dry fresco. The walls were prepared with a mixture of mud, straw, and reeds that were covered with a lime paste. The sculptures are constructed with a wooden armature, straw, reeds, and plaster. The colors in the paintings and on the sculptures were done with mineral pigments as well as gold and silver leaf.

The art also reflects the changes in religious belief and ritual at the pilgrim site. In the early caves, jataka stories (about Buddha’s previous incarnations) were commonly depicted. During the Tang dynasty, Pure Land Buddhism became very popular. This promoted the Buddha Amitabha, who helped the believer achieve rebirth in his Western Paradise, where even sinners are permitted, sitting within closed lotus buds listening to the heavenly sounds and the sermon of the Buddha, thereby purifying themselves. Various Paradise paintings decorate the walls of the cave-temples of this period, each representing the realm of a different Buddha. Their Paradises are depicted as sumptuous Chinese palace settings.

When the Silk Road was abandoned under the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), oasis towns lost their importance, and many were deserted. Although the Mogao caves were not completely abandoned, by the nineteenth century they were largely forgotten, with only a few monks staying at the site.

The Song Dynasty

When the Tang dynasty (618–907) collapsed, a period of upheaval, rapid succession of dynasties, and multiple kingdoms followed. In the mid-tenth century, a general named Zhou Kuangyin reunified China, establishing the Song dynasty (960–1279) with himself as the first ruler, Emperor Taizu. The Song dynasty was divided into two periods: the Northern Song (960–1126), the physically larger empire, and the Southern Song (1127–1279). Overall, it was a time of stability and economic, cultural, and artistic prosperity.

Increased population, advanced agricultural techniques, and booming trade and commerce led to a thriving economy during both the Northern and Southern Song. The world’s first governmental paper money was issued in the 1120s. Despite the empire’s many successes, the state lacked the same degree of military strength that the previous Tang dynasty had enjoyed. Instead, the Song rulers took advantage of the empire’s economic strength and made large annual gifts to neighboring states to secure the peace that its armies could not. Despite the payoffs, a seminomadic people called the Jurchens eventually conquered the capital of Kaifeng in 1126, bringing an end to the Northern Song. The Song court fled south and established a new capital in the city that is today known as Hangzhou, beginning what is called the Southern Song dynasty.

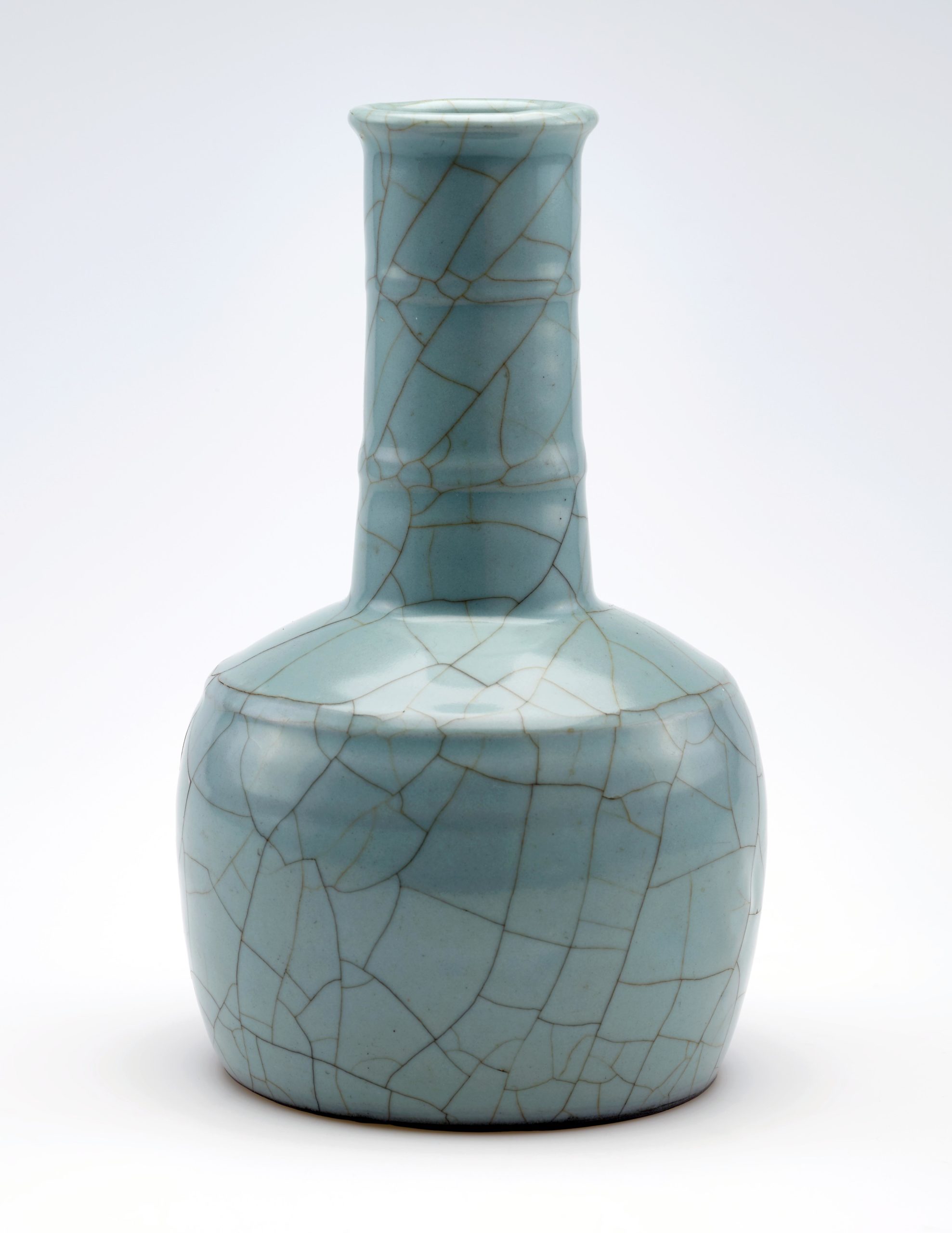

The Song government’s relative military weakness was disturbing to many Chinese intellectuals. They developed a defensive, inward-looking strategy and became less open to adopting foreign styles and ideas. Buddhism, for example, was to some degree rejected for its foreign origin, and the native philosophies of Confucianism and Daoism experienced a strong resurgence. With the Confucian revival came a new interest in ancient culture, or antiquarianism. The Song dynasty is often called an age of protoarchaeology and a period when great collectors and connoisseurs of art flourished both in and outside the court. Pre-Qin dynasty (221–206 B.C.E.) bronzes and jades began to be collected and were imitated and reproduced in creative new interpretations. Reverence for and reference to the past became increasingly important factors in Chinese art.

The Song court established an Imperial Painting Academy in the palace. Painters from all over the country were recruited to serve the needs of the court. The varied traditions, under the auspices of the court, blended together into a distinctive Song academic style. It valued a naturalistic and descriptive representation of the physical world. Scholar officials chosen through the civil service examination also had a major impact on the arts. They developed a style that rejected the descriptive realism of the professional and court painters, valuing spontaneity and a type of brushwork that was informed by their study of calligraphy. Many favored painting in ink alone without color. For the scholar (or amateur) artists, painting was a means of personal expression pursued for the enjoyment of the artist and for the sharing of ideas with his circle of friends.

Ceramics made in the Song dynasty stand out as world masterpieces. Song ceramics were supremely accomplished in terms of technical expertise, creativity, and the aesthetic harmony between the shape and glaze of a vessel. The Song court favored elegant ceramics with simple and refined forms and subtle gazes, reflecting the aesthetic values and introspective atmosphere of the time. Alongside the simpler ceramics that suited court tastes, the popular market was extremely vibrant and productive in making ceramics with bold designs and multiple colors.

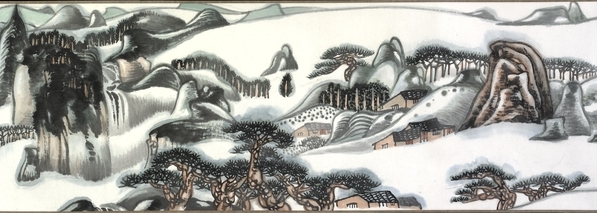

Chinese Landscape Painting

Landscape painting is traditionally at the top of the hierarchy of Chinese painting styles. It is very popular and is associated with refined scholarly taste. The Chinese term for “landscape” is made up of two characters meaning “mountains and water.” It is linked with the philosophy of Daoism, which emphasizes harmony with the natural world.

Chinese artists do not usually paint real places but imaginary, idealized landscapes. The Chinese phrase woyou expresses this idea of “wandering while lying down.” In China, mountains are associated with religion because they reach up towards the heavens. People therefore believe that looking at paintings of mountains is good for the soul.

Chinese painting in general is seen as an extension of calligraphy and uses the same brushstrokes. The colors are restrained and subtle and the paintings are usually created in ink on paper, with a small amount of watercolor. They are not framed or glazed but mounted on silk in different formats such as handscrolls, hanging scrolls, and album leaves.

Handscrolls

Paintings in China are not usually hung on walls, permanently on display, but are rather often mounted as handscrolls, rolled up and only brought out for special viewings. This is partly due to the delicate nature of the ink and color, which would fade if left exposed to light for a long time. The unrolling of a scroll is an act of some ceremony. Connoisseurs do not view the painting from a distance, as in the West, but approach close to “read the painting.”

Handscrolls are designed to be unrolled, from right to left, revealing one scene at a time. As each new section is unrolled, the previous scene is rolled up, giving the viewer the feeling of a journey through the landscape.

In this handscroll, Zhu Xiuli reinterprets tradition with his twentieth-century version of a traditional landscape. The various elements are organized and controlled, with movement provided by the lines of trees flowing through the scroll. Zhu’s painting is fresh, and his use of color washes accomplished.

Hanging Scrolls

Hanging scrolls are typically used for vertical compositions. They are hung for display using a cord, which is attached to a thin wooden strip along the top of the silk mounting. There is a wooden rod at the bottom which provides the necessary weight for the painting to hang smoothly. It is also useful when the painting is rolled up for storage.

This example of a hanging scroll by Dong Qichang shows a clear structure. It is divided into a foreground, with four mountain areas in the middle and background as well as sub-divisions. The viewer’s eye is drawn upwards from the foreground to the top peak. The lines of trees and the ink dots showing vegetation mark the contours of the landscape.

Album Leaves

In China, the album format is more intimate than the hanging scroll or handscroll formats. Chinese painting albums usually consist of up to twelve folded pages, with wood or brocade-covered card covers.

The albums are relatively small, up to 120 square cm, and often include paintings as well as calligraphy. The paintings and calligraphy usually work together, sometimes with a poem on one page and a small painting illustrating it on a facing page. The paintings might be by one artist or a group of different artists, who perhaps joined together to dedicate their works to a friend for a special occasion.

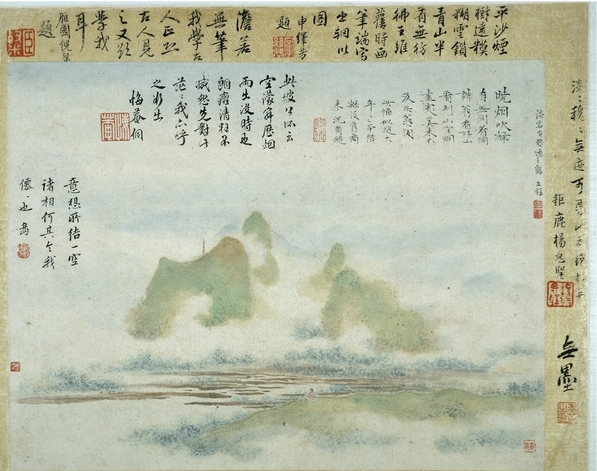

In this album leaf, the artist uses color wash only, with no ink and no outline. This technique is usually used on flower paintings and its use in a landscape gives an other-worldly quality to the scene. Many well-known writers have inscribed the album leaf and on the right-hand margin is the simple comment “no ink.

- The English term “jade” is used to translate the Chinese word yu, which refers to a number of minerals including nephrite, jadeite, serpentine and bowenite, while "jade" refers only to nephrite and jadeite. Chemically, nephrite is a calcium magnesium silicate and is white in color. However, the presence of copper, chromium and iron produces colors ranging from subtle grey-greens to brilliant yellows and reds. Jadeite, which was very rarely used in China before the eighteenth century, is a silicate of sodium and magnesium and comes in a wider variety of colors than nephrite. ↵

a graphic symbol that conveys its meaning through its pictorial resemblance to a physical object. for 'bicycle', for 'car', for 'heart', etc.

a graphic symbol that represents an idea or concept, independent of any particular language, and specific words or phrases. For example, for 'happy', for 'angry', for 'sad', etc. These are independent of language, so can be understood by native English, Spanish, Arabic, Chinese, etc. speakers alike.

pieces of ox scapula and turtle plastron, which were used for pyromancy – a form of divination – in ancient China, mainly during the late Shang dynasty. Scapulimancy is the correct term if ox scapulae were used for the divination, plastromancy if turtle plastrons were used.

A motif common on Chinese ritual bronze vessels from the Shang and Zhou dynasties. The design typically consists of a frontal, bilaterally symmetrical zoomorphic mask with a pair of raised eyes and no lower jaw area.